1 Alexander Bogdanov and the Short History of the Kultintern 1 by John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Who and What Is Peter Petroff

The University of Manchester Research In and out of the swamp Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K. (2013). In and out of the swamp: the unpublished autobiography of Peter Petroff. Scottish Labour History, 48, 23-51. Published in: Scottish Labour History Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 In and out of the swamp: the unpublished autobiography of Peter Petroff1 Kevin Morgan ‘Who and what is Peter Petroff?’ The question infamously put by the pro-war socialist paper Justice in December 1915 has only ever been partly answered. As the editors of Justice well knew, Petroff (1884-1947) was a leading figure on the internationalist wing of the British Socialist Party (BSP) whom John Maclean had recently invited to Glasgow on behalf of the party’s Glasgow district council. -

Communists and the Labour Party

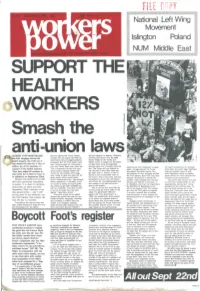

FILE , I cnpv National ~ Left·Wing Movement Islington Poland NUM Middle East ::.;:~:;:;:;:;::::::::::::::::::::::::::~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:;:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~::::::::;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:;:;~~~~~: THE HEALTH Smash,the anti-union laws. Al.-MOST FIVE MONTHS after workers against the Tories. Miners, Bill 't~e designed to destroy. Effective he firSt stoppage during the dockers and, of cour,se, tile Fleet St. working class action is ,to be made totally illegal by the Tories. Suc ealth dispute, the TUC has at electricians, hBve. all '$taged solidarity stoppages. But the TUC leaders have cessful action in support of the health last named the date for a Day of been running scared of a showdown workers must bring the organised Action, by all its ~embers, in with the Tories. Even now, when the working class into a collision with the battle could have threatened to spear the health workers and on strength support of the health workers. TUC is eventually forced into supp law. The Tories will not hesitate to head a struggle against the Tories ening their anti-union legal machinery They have asked all workers to orti ng action, because neither the use that law if they think they can throughout the public sector. But with yet another round of anti- get away with it. Victory in this in stop work for at least an hour in Tories nor the workers will budge, the prospect of such struggles terrifies union legislation aimed at making they refuse to issue any clear call for stance is sure to embolden them in the TUC leaders. Each time they have secret ballots for union officials and in solidarity on Septemller 22nd. -

Nationality Issue in Proletkult Activities in Ukraine

GLOKALde April 2016, ISSN 2148-7278, Volume: 2 Number: 2, Article 4 GLOKALde is official e-journal of UDEEEWANA NATIONALITY ISSUE IN PROLETKULT ACTIVITIES IN UKRAINE Associate Professor Oksana O. GOMENIUK Ph.D. (Pedagogics), Pavlo TYchyna Uman State Pedagogical UniversitY, UKRAINE ABSTRACT The article highlights the social and political conditions under which the proletarian educational organizations of the 1920s functioned in the context of nationalitY issue, namelY the study of political frameworks determining the status of the Ukrainian language and culture in Ukraine. The nationalitY issue became crucial in Proletkult activities – a proletarian cultural, educational and literary organization in the structure of People's Commissariat, the aim of which was a broad and comprehensive development of the proletarian culture created by the working class. Unlike Russia, Proletkult’s organizations in Ukraine were not significantlY spread and ceased to exist due to the fact that the national language and culture were not taken into account and the contact with the peasants and indigenous people of non-proletarian origin was limited. KeYwords: Proletkult, worker, culture, language, policY, organization. FORMULATION OF THE PROBLEM IN GENERAL AND ITS CONNECTION WITH IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL TASKS ContemporarY social transformations require detailed, critical reinterpreting the experiences of previous generations. In his work “Lectures” Hegel wrote that experience and history taught that peoples and governments had never learnt from history and did not act in accordance with the lessons that historY could give. The objective study of Russian-Ukrainian relations require special attention that will help to clarify the reasons for misunderstandings in historical context, to consider them in establishing intercommunication and ensuring peace in the geopolitical space. -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

People, Place and Party:: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911

Durham E-Theses People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911 Young, David Murray How to cite: Young, David Murray (2003) People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk People, Place and Party: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911 David Murray Young A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of Politics August 2003 CONTENTS page Abstract ii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1- SDF Membership in London 16 Chapter 2 -London -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cimpean, Oana Carmina, "Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2283. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LOUIS ARAGON AND PIERRE DRIEU LA ROCHELLE: SERVILITYAND SUBVERSION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Oana Carmina Cîmpean B.A., University of Bucharest, 2000 M.A., University of Alabama, 2002 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 August, 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dissertation advisor Professor Alexandre Leupin. Over the past six years, Dr. Leupin has always been there offering me either professional advice or helping me through personal matters. Above all, I want to thank him for constantly expecting more from me. Professor Ellis Sandoz has been the best Dean‘s Representative that any graduate student might wish for. I want to thank him for introducing me to Eric Voegelin‘s work and for all his valuable suggestions. -

The Russian Revolution from Lenin to Stalin 1917-1929 2Nd Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION FROM LENIN TO STALIN 1917-1929 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward Hallett Carr | 9780333993095 | | | | | The Russian Revolution from Lenin to Stalin 1917-1929 2nd edition PDF Book Philosophy Economic determinism Historical materialism Marx's dialectic Marx's method Philosophy of nature. Rosmer himself was conscripted in May and so could not attend the Zimmerwald conference held in Switzerland in September , when a first puny attempt was made to bring together the remnants of the antiwar Left. Aleksandr Kerensky, the prime…. Lenin was prepared to replace the Union he had originally proposed with a looser association in which the centralized powers might be limited to defense and international relations alone. Concerning the political disenfranchisement of the capitalist social-class in Bolshevik Russia, Lenin said that "depriving the exploiters of the franchise is a purely Russian question, and not a question of the dictatorship of the proletariat, in general. The Communists, therefore, are, on the one hand, practically the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the lines of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement. However, he ruled by terror, and millions of his own There are problems in the interpretation: Carr designates the overtrow of the Provisional Government as a coup; the inadequate control of workers in the nationalized industry does not derive from the inability of workers but from the given circumstances, etc. -

Theory of Money and Credit Centennial Volume.Indb

The University of Manchester Research The Influence of the Currency-Banking Dispute on Early Viennese Monetary Theory Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Mccaffrey, M., & Hülsmann, J. G. (Ed.) (2012). The Influence of the Currency-Banking Dispute on Early Viennese Monetary Theory. In The Theory of Money and Fiduciary Media: Essays in Celebration of the Centennial (pp. 127- 165). Mises Institute. Published in: The Theory of Money and Fiduciary Media Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 6 M ATTHEW MC C AFFREY The Influence of the Currency-Banking Dispute on Early Viennese Monetary Theory INTRODUCTION Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century witnessed one of the most remarkable moments in the history of monetary theory. In consecu- tive years, three young economists in Vienna published treatises involving the problems of money and banking: Rudolf Hilferding’s Finance Capital in 1910, Joseph Schumpeter’s Th e Th eory of Economic Development in 1911, and Ludwig von Mises’s Th e Th eory of Money and Credit in 1912. -

ALL-ROUND DEVELOPMENT of VLADIMIR LENIN's PERSONALITY Javed Akhter, Khair Muhammad and Naila Naz M.Phil Scholar, Department Of

International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research Method Vol.3, No.1, pp.23-34, March 2016 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ALL-ROUND DEVELOPMENT OF VLADIMIR LENIN’S PERSONALITY Javed Akhter, Khair Muhammad and Naila Naz M.Phil Scholar, Department of English Literature and Linguistics, University of Balochistan Quetta Balochistan Pakistan ABSTRACT: The study investigates the personality of Vladimir Lenin, in the light of Stephen R. Covey’s suggested habits, expounded in his books, “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” and “The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to greatness”, following the most eminent Russian physiologist and psychologist I. P. Pavlov’s theory of classical behaviourism. Stephen R. Covey’s thought provoking and trend breaking book: “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” suggests seven habits and paradigms to become highly effective personality. He introduced the eighth habit in his innovative and challenging book “The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness.” Therefore, his suggested eight habits, and paradigms, which are based on I. P. Pavlov’s theory of classical behaviourism. This paper would use the popped up chunks of I. P. Pavlov’s behaviourist theory to analyse how the process of habit formation influenced the effective and great personalities of the world. Therefore, the present study will enable the readers to confront Pavlov’s classical behaviourist theory of habit formation through stimuli and responses. The readers are also expected to abandon the bad habits and adopt the good ones. These infrequent but subtle hints serve as a model of effective as well as great personality of the world. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zoeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) dr section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Nordic Race - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Nordic race - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordic_race From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Nordic race is one of the putative sub-races into which some late 19th- to mid 20th-century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race. People of the Nordic type were described as having light-colored (typically blond) hair, light-colored (typically blue) eyes, fair skin and tall stature, and they were empirically considered to predominate in the countries of Central and Northern Europe. Nordicism, also "Nordic theory," is an ideology of racial supremacy that claims that a Nordic race, within the greater Caucasian race, constituted a master race.[1][2] This ideology was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in some Central and Northern European countries as well as in North America, and it achieved some further degree of mainstream acceptance throughout Germany via Nazism. Meyers Blitz-Lexikon (Leipzig, 1932) shows famous German war hero (Karl von Müller) as an example of the Nordic type. 1 Background ideas 1.1 Attitudes in ancient Europe 1.2 Renaissance 1.3 Enlightenment 1.4 19th century racial thought 1.5 Aryanism 2 Defining characteristics 2.1 20th century 2.2 Coon (1939) 2.3 Depigmentation theory 3 Nordicism 3.1 In the USA 3.2 Nordicist thought in Germany 3.2.1 Nazi Nordicism 3.3 Nordicist thought in Italy 3.3.1 Fascist Nordicism 3.4 Post-Nazi re-evaluation and decline of Nordicism 3.5 Early criticism: depigmentation theory 3.6 Lundman (1977) 3.7 Forensic anthropology 3.8 21st century 3.9 Genetic reality 4 See also 5 Notes 6 Further reading 7 External links Attitudes in ancient Europe 1 of 18 6/18/2013 7:33 PM Nordic race - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordic_race Most ancient writers were from the Southern European civilisations, and generally took the view that people living in the north of their lands were barbarians.