Göran Bolin & Michael Forsman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Dolce Vita Actress Anita Ekberg Dies at 83

La Dolce Vita actress Anita Ekberg dies at 83 Posted by TBN_Staff On 01/12/2015 (29 September 1931 – 11 January 2015) Kerstin Anita Marianne Ekberg was a Swedish actress, model, and sex symbol, active primarily in Italy. She is best known for her role as Sylvia in the Federico Fellini film La Dolce Vita (1960), which features a scene of her cavorting in Rome's Trevi Fountain alongside Marcello Mastroianni. Both of Ekberg's marriages were to actors. She was wed to Anthony Steel from 1956 until their divorce in 1959 and to Rik Van Nutter from 1963 until their divorce in 1975. In one interview, she said she wished she had a child, but stated the opposite on another occasion. Ekberg was often outspoken in interviews, e.g., naming famous people she couldn’t bear. She was also frequently quoted as saying that it was Fellini who owed his success to her, not the other way around: "They would like to keep up the story that Fellini made me famous, Fellini discovered me", she said in a 1999 interview with The New York Times. Ekberg did not live in Sweden after the early 1950s and rarely visited the country. However, she welcomed Swedish journalists into her house outside Rome and in 2005 appeared on the popular radio program Sommar, and talked about her life. She stated in an interview that she would not move back to Sweden before her death since she would be buried there. On 19 July 2009, she was admitted to the San Giovanni Hospital in Rome after falling ill in her home in Genzano according to a medical official in the hospital's neurosurgery department. -

Joe Hill Joe Hill

politik und mit seinem gesellschaftlichen Engagement. a quiet, clear lake, and in other details such as a garden LEBEN UM JEDEN PREIS ist überhaupt nicht sentimental. Der gate, a door handle, a door to Widerberg's house and a Film wird getragen von Gefühlen des Vermissens und der Liebe. cemetery. He is present through his criticism of film poli• Monika Tunbäck-Hanson, in: Göteborgs Posten, 18.9.1998 tics and through his social commitment. LIFE AT ANY COST is not sentimental at all. The domi• Biofilmographie nant feelings in the film are a sense of loss and of love. Stefan Jarl wurde am 18. März 1941 im südschwedischen Skara Monika Tunbäck-Hanson, in: Göteborgs Posten, Septem• geboren. Ende der sechziger Jahre gründete er eine Gewerkschaft ber 18th, 1998 für Filmarbeiter, einen nicht-kommerziellen Verleih ('Film Cent• rum'), ein Kino ('Folkets Bio' - Volkskino) sowie eine Filmzeit• Biofilmography schrift. Stefan Jarl was born on March 18th, 1941 in Skara (South Stefan Jarl arbeitete außerdem als Produktionsleiter nicht nur für of Sweden). He made his first films in the late sixties. In Bo Widerberg, sondern auch für andere schwedische Regisseure, the seventies he founded a union for filmworkers, a non• wie z.B. Stig Björkman, Mai Zetterling und Arne Sucksdorff. commercial film distribution company, a cinema ('Folkets-Bio'- People's Cinema) and a magazine. Stefan Jarl also worked as a production manager not only JOE HILL for Bo Widerberg, but also for a number of Swedish di• rectors, such as Stig Björkman, Mai Zetterling and Arne Sucksdorff. Land: Schweden 1971. Produktion: Sagittarius. Regie und Buch: Bo Widerberg. -

Marie Göranzon

Marie Göranzon ABOUT Birth 1942 Language Swedish, English Eyes Blue Hair Blonde FILM AND TV PRODUCTIONS 2020 Se upp för Jönssonligan (Feature) Dir: Tomas Alfredson. FLX 2020 Bröllop, begravning & dop (TV series) Dir: Colin Nutley. Sweetwater 2020 Orca (Feature) Dir: Josephine Bornebusch. Warner Bros. 2017 2060 (TV Movie) Dir: Henrik Hellström. SVT 2013 Allt faller (TV Series) Dir: Henrik Schyffert. TV4 2012 Blondie (Feature) Dir: Jesper Ganslandt. Fasad 2007 Beck - I Guds namn (TV Series) Dir: Kjell Sundvall. Filmlance 2007 Beck - Det tysta skriket (TV Series) Dir: Harald Hamrell. Filmlance 2007 Beck - Den japanska shungamålningen (TV Series) Dir: Kjell Sundvall. Filmlance 2007 Beck - Den svaga länken (TV Series) Dir: Harald Hamrell. Filmlance 2007 Hoppet (Feature) Dir: Petter Næss. Sonet Film 2006 Beck - Advokaten (TV Series) Dir: Kjell Sundvall. Filmlance 2006 Beck - Gamen (TV Series) Dir: Kjell Sundvall. Filmlance 2006 Beck - Flickan i jordkällaren (TV Series) Dir: Harald Hamrell. Filmlance 2005 Mun mot mun (Feature) Dir: Björn Runge. Sonet Film 2005 Den bästa av mödrar (Feature) Dir: Klaus Härö. Matila Röhr Productions 2004 Stenjäveln (Short) Dir: Jens Jonsson 2004 Dag och natt (Feature) Dir: Simon Staho. Zentropa 2003 Spaden (Short) Dir: Jens Jonsson 2003 Skenbart: En film om tåg (Feature) Dir: Peter Dalle. S/S Fladen 2002 Alla älskar Alice (Feature) Dir: Richard Hobert. Sonet Film 2002 Beck - Skarpt läge (TV Series) Dir: Harald Hamrell. Filmlance 2002 Beck - Pojken i glaskulan (TV Series) Dir: Daniel Lind Lagerlöf. Filmlance 2002 Beck - Annonsmannen (TV Series) Dir: Daniel Lind Lagerlöf. Filmlance 2002 Beck - Okänd avsändare (TV Series) Dir: Harald Hamrell. Filmlance 2002 Beck - Enslingen (TV Series) Dir: Kjell Sundvall. -

The Other in Contemporary Swedish Cinema

Division of Art History and Visual Studies Department of Arts and Cultural Sciences Lund University Sweden The Other in Contemporary Swedish Cinema Portrayals of Non-White Swedes in Swedish Cinema 2000-2010 A Master’s Thesis for the Degree Master of Arts (Two Years) in Visual Culture Elina Svantesson Spring 2012 Supervisor: Ingrid Stigsdotter 1 LUND UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT DIVISION OF ART HISTORY AND VISUAL STUDIES / FILM STUDIES MASTER OF ARTS IN VISUAL CULTURE The other in contemporary Swedish cinema Portrayals of non-white Swedes in Swedish cinema 2000-2010 Elina Svantesson The evident place that film has in society makes it a powerful medium that journeys across borders of nationalities, sexualities, and ethnicities. Film represents, and since representation is of importance when acquiring knowledge and a continuous changing medium, it must be scrutinised continuously. In this thesis, contemporary Swedish mainstream cinema (2000-2010) has been examined for its representations of immigrants, Arabs and non-white Swedes. Concepts of culture, identity and whiteness are used to make sense of these representations and politics is shown to have a strong impact on the medium. Making use of the notion of “whiteness”, the thesis suggests that non-white Swedes are considered different to white Swedes. The Arab, for example, is given many negative traits previously seen in anti-Semitic, pre-WWII images of the Jew. Furthermore, many films were proven to exclude non-white Swedes from a depicted society, geographical and social. This exclusion of “the other” can be considered a representation in itself, a reflection of a divided Swedish society. Non-white Swedes are a large group of people, and it is argued that instead of portraying a static, shallow image of non-white Swedes, the Swedish film industry and society, could benefit from anticipating a new cinematic society and by including this group. -

Half a Century with the Swedish Film Institute

Swedish #2 2013 • A magazine from the Swedish Film Institute Film 50Half a century with the Swedish Film Institute CDirector Lisah Langsethe exploresc identityk issuesi nin Hotel g in www.sfi.se scp reklambyrå Photo: Simon Bordier Repro: F&B Repro: Factory. Bordier Simon Photo: reklambyrå scp One million reasons to join us in Göteborg. DRAGON AWARD BEST NORDIC FILM OF ONE MILLION SEK IS ONE OF THE LARGEST FILM AWARD PRIZES IN THE WORLD. GÖTEBORG INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IS ALSO THE MAIN INDUSTRY WINDOW FOR NEW NORDIC FILM AND TALENT, FEATURING NORDIC FILM MARKET AND NORDIC FILM LAB. 1,000 SCREENINGS • 500 FILMS • 23 VENUES • 160,000 VISITS • WWW.GIFF.SE WELCOME Director, International Department Pia Lundberg Fifty and counting Phone +46 70 692 79 80 [email protected] 2013 marks the Swedish Film Institute’s various points in time. The films we support 50th anniversary. This gives us cause to look today are gradually added to history, giving back to 1963 and reflect on how society and that history a deeper understanding of the Festivals, features the world at large have changed since then. world we currently live in. Gunnar Almér Phone +46 70 640 46 56 Europe is in crisis, and in many quarters [email protected] arts funding is being cut to balance national IN THIS CONTEXT, international film festivals budgets. At the same time, film has a more have an important part to play. It is here that important role to play than ever before, we can learn both from and about each other. -

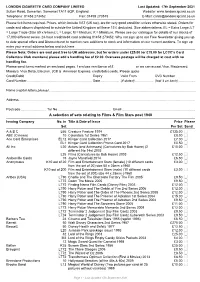

LCCC Thematic List

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W Inte R 2 0 18 – 19

WINTER 2018–19 BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE 100 YEARS OF COLLECTING JAPANESE ART ARTHUR JAFA MASAKO MIKI HANS HOFMANN FRITZ LANG & GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM INGMAR BERGMAN JIŘÍ TRNKA MIA HANSEN-LØVE JIA ZHANGKE JAMES IVORY JAPANESE FILM CLASSICS DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT IN FOCUS: WRITING FOR CINEMA 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 CALENDAR DEC 9/SUN 21/FRI JAN 2:00 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 Introduction by Jan Pinkava 7:00 Fanny and Alexander BERGMAN P. 15 1/SAT TRNKA P. 12 3/THU 7:00 Full: Home Again—Tapestry 1:00 Making a Performance 1:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. 6 4:30 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari P. 5 WORKSHOP P. 6 Reimagined Judith Rosenberg on piano 4–7 Five Tables of the Sea P. 4 5:30 The Good Soldier Švejk TRNKA P. 12 LANG & EXPRESSIONISM P. 16 22/SAT Free First Thursday: Galleries Free All Day 7:30 Persona BERGMAN P. 14 7:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 6:00 The Firemen’s Ball P. 29 5/SAT 2/SUN 12/WED 8:00 The Apartment P. 19 6:00 Future Landscapes WORKSHOP P. 6 12:30 Scenes from a 6:00 Arthur Jafa & Stephen Best 23/SUN Marriage BERGMAN P. 14 CONVERSATION P. 6 9/WED 2:00 Boom for Real: The Late Teenage 2:00 Guided Tour: Old Masters P. 6 7:00 Ugetsu JAPANESE CLASSICS P. 20 Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat P. 15 12:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. -

The Historian-Filmmaker's Dilemma: Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Historica Upsaliensia 210 Utgivna av Historiska institutionen vid Uppsala universitet genom Torkel Jansson, Jan Lindegren och Maria Ågren 1 2 David Ludvigsson The Historian-Filmmaker’s Dilemma Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius 3 Dissertation in History for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy presented at Uppsala University in 2003 ABSTRACT Ludvigsson, David, 2003: The Historian-Filmmaker’s Dilemma. Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius. Written in English. Acta Universitatis Upsalien- sis. Studia Historica Upsaliensia 210. (411 pages). Uppsala 2003. ISSN 0081-6531. ISBN 91-554-5782-7. This dissertation investigates how history is used in historical documentary films, and ar- gues that the maker of such films constantly negotiates between cognitive, moral, and aes- thetic demands. In support of this contention a number of historical documentaries by Swedish historian-filmmakers Olle Häger and Hans Villius are discussed. Other historical documentaries supply additional examples. The analyses take into account both the produc- tion process and the representations themselves. The history culture and the social field of history production together form the conceptual framework for the study, and one of the aims is to analyse the role of professional historians in public life. The analyses show that different considerations compete and work together in the case of all documentaries, and figure at all stages of pre-production, production, and post-produc- tion. But different considerations have particular inuence at different stages in the produc- tion process and thus they are more or less important depending on where in the process the producer puts his emphasis on them. -

Joe Hill Film Buff

BO WIDERBERG’s LOST MASTERPIECE JOE HILL VICTORIAN TRADES HALL 54 VICTORIA ST CARLTON (CNR OF LYGON ST) CENTENARY THURSDAY 19 NOVEMBER AT 5.15 PM JOE HILL 1915-2015 CENTENARY CELEBRATION The critically acclaimed 1971 film Joe Hill, by renowned Swedish director Bo Widerberg (Elvira Madigan), won the Cannes Jury Prize in 1971. Lost and unavailable for many decades, it has now been restored and digitally remastered by the National Library of Sweden. We are offering you a unique opportunity to see this long-lost masterpiece. Joe Hill was a Swedish-American immigrant and itinerant labourer who fought for the rights and unity of workers. He was executed by firing squad in Utah on 19 November 1915, after being convicted of murder on circumstantial evidence. A poet, songwriter and IWW activist, he was commemorated by Joan Baez in the song ’I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill JOE HILL Last Night’. Bo Widerberg’s film dramatises Joe Hill’s life and impoverished, unorganised immigrant labour in the US during the early 20th century. His story is still relevant to workers today. The Victorian Trades Hall Choir will perform ‘I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night’, and Phil CENTENARY Cleary will speak about Joe Hill and his significance to workers today. THE EVENT WHERE WHEN 5:15pm Victorian Trades Hall Thursday 19 Drinks and snacks 54 Victoria st Carlton November at Bella Union Bar (corner Lygon Street) 6:00pm Film screening in New Council Chamber Enquiries: Teresa Pitt at [email protected], ph 0419 438 221 Graham Hardy at [email protected], ph 0447 126 471 We are grateful for generous sponsorship from Victorian Trades Hall Council and The Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Victorian Branch Design by Atticus Silverson Joe Hill photograph (between c. -

From 5 to 13 October at Fiere Di Parma

Press Release MERCANTEINFIERA AUTUMN THE POETRY OF THE HEEL, ITALIAN MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND FOUR CENTURIES OF ART HISTORY From 5 to 13 October at Fiere di Parma Mercanteinfiera, the Fiere di Parma international exhibition of antiques, modern antiques, design and vintage collectibles, is an increasingly “fusion” event. Protagonists of the 38th edition are the Villa Foscarini Rossi Shoes Museum of the LVMH Group and the BDC Art Gallery in Parma, owned by Lucia Bonanni ad Mauro del Rio, curators of the two collateral exhibitions. On the one hand, stylists such as Dior, Kenzo, Yves Saint Laurent and Nicholas Kirkwood highlighted by the far-sightedness of the entrepreneur Luigino Rossi, the Muse- um’s founder. On the other, masters of the visual language such as Ghirri, Sottsass, Jodice, as well as the paparazzi. With Lino Nanni and Elio Sorci, we will dive into the years of the exuberant Dolce Vita. (Parma, 30 September 2019) - At the beginning there were” pianelle”, or “chopines”, worn by both aristocratic women and commoners to protect their feet from mud and dirt. They could be as high as 50 cm (but only for the richest ladies), while four centuries later Mari- lyn Monroe would build her image on a relatively very modest 11-cm peep toe heel. For Yves Saint Laurent the perfect stride required a 9-cm heel. This was too high for the Swinging Sixties of London and Twiggy, when ballerinas were the footwear of choice. Whether high, low, with a 9 or 11cm heel, shoes have always been the best-loved accesso- ry of fashion victims and many others and they are the protagonists of the collateral exhi- bition “In her Shoes. -

SAAS Conference Program (P

Celebrated, Contested, Criticized: Anita Ekberg, a Swedish Sex Goddess in Hollywood Wallengren, Ann-Kristin 2018 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wallengren, A-K. (2018). Celebrated, Contested, Criticized: Anita Ekberg, a Swedish Sex Goddess in Hollywood. 34. Abstract from The Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS), . Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 10th Biennial Conference of The Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS) OPEN COVENANTS: PASTS AND FUTURES OF GLOBAL AMERICA Friday September 28th – Sunday September 30th 2018 Stockholm, Sweden PROGRAM MAGNUS BERGVALLS STIFTELSE Welcome to the 10th biennial conference of the Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS) Stockholm, September 28–30, 2018 Keynote speakers: Prof. -

Winter, 2009; Fridays at 7 Pm; 177 Lawrence Hall FREE and Open to the Public

Swedish Film Series Winter, 2009; Fridays at 7 pm; 177 Lawrence Hall FREE and open to the public Probably no other nation of comparable population can match the artistic success of Sweden in the film industry. Yet few Americans—aside from a small group of Ingmar Bergman fans—could name even one Swedish film. This series aims to change that. Come sample a rich variety of wonderful films made between 1951 and 2006. All nine films are in Swedish with subtitles in English. Each film is preceded by a short presentation about a particular aspect of Swedish culture (e.g., food, geography, language) as well as a brief intro- duction to the film itself. At the conclusion of the film, audience members who wish to stay for another 10-15 minutes are invited to participate in a short, not-overly-academic discussion of the film. Lawrence Hall is located in the central part of the University of Oregon cam- pus, about 100 yards north of the intersection of 13th and University. Please use the building’s south entrance just below the AAA Library, and proceed straight ahead to 177. 9 January when Elisabeth parks her car in As It Is in Heaven (Så som i Himmelen) 2004 a loading zone and is ticketed by Directed by Kay Pollak Gudrun. Despite this shaky start, A successful international conductor suddenly interrupts his a friendship grows between the career and returns alone to his childhood village in Norrland, two. Elisabeth, a gynecologist, is in Sweden’s far north. It doesn’t take long before he is asked to sexy and confident.