Brigham Young on Life and Death 91

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Men Never Cry”: Teaching Mormon Manhood in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Sociological Focus ISSN: 0038-0237 (Print) 2162-1128 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/usfo20 “Men never cry”: Teaching Mormon Manhood in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints J. E. Sumerau, Ryan T. Cragun & Trina Smith To cite this article: J. E. Sumerau, Ryan T. Cragun & Trina Smith (2017): “Men never cry”: Teaching Mormon Manhood in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Sociological Focus, DOI: 10.1080/00380237.2017.1283178 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2017.1283178 Published online: 06 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 10 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=usfo20 Download by: [173.168.25.232] Date: 13 March 2017, At: 17:55 SOCIOLOGICAL FOCUS http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2017.1283178 “Men never cry”: Teaching Mormon Manhood in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints J. E. Sumerau, Ryan T. Cragun, and Trina Smith University of Tampa ABSTRACT We examine the ways Mormon leaders establish “what it means to be a man” for their followers. Based on content analysis of over 40 years of archival material, we analyze how Mormon leaders represent manhood as the ability to signify control over self and others as well as an inability to be controlled. Specifically, we demonstrate how these representations stress controlling the self, emotional and sexual expression, and others while emphasizing the development of self-reliance and independence from others’ control. -

Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2

Episode 27 Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2 NARRATOR: This is Stories from General Conference, volume two, on the topic of Priesthood Power. You are listening to the Mormon Channel. Worthy young men in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have the privilege of receiving the Aaronic Priesthood. This allows them to belong to a quorum where they learn to serve and administer in some of the ordinances of the Church. In the April 1997 General Priesthood Meeting, Elder David B. Haight reminisced about his youth and how the priesthood helped him progress. (Elder David B. Haight, Priesthood Session, April 1997) “Those of you who are young today--and I'm thinking of the deacons who are assembled in meetings throughout the world--I remember when I was ordained a deacon by Bishop Adams. He took the place of my father when he died. My father baptized me, but he wasn't there when I received the Aaronic Priesthood. I remember the thrill that I had when I became a deacon and now held the priesthood, as they explained to me in a simple way and simple language that I had received the power to help in the organization and the moving forward of the Lord's program upon the earth. We receive that as 12-year-old boys. We go through those early ranks of the lesser priesthood--a deacon, a teacher, and then a priest--learning little by little, here a little and there a little, growing in knowledge and wisdom. That little testimony that you start out with begins to grow, and you see it magnifying and you see it building in a way that is understandable to you. -

December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, and Temple

THE CHURCH OF JESUS GHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS OFFICE OF THE FIRST PRESIDENCY 47 EAST SOUTH TEMPLE STREET, SALT LAKE 0ITY, UTAH 84150-1200 December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, andTemple Presidents; Bishops and Branch Presidents; Stake, District, Ward,and Branch Councils (To be read in sacrament meeting) Dear Brothers and Sisters: Age-Group Progression for Children and Youth We desire to strengthen our beloved children and youth through increased faith in Jesus Christ, deeper understanding of His gospel, and greater unity with His Church and its members. To that end, we are pleased to announce that in January 2019 children will complete Primary and begin attending Sunday School and Young Women or Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups atth e beginning of January in the year they turn 12. Likewise, young women will progress between Young Women classes and young men between Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups at the beginning of January in the year they turn 14 and 16. In addition, young men will be eligible for ordinationto the appropriate priesthood office in January of the year they tum 12, 14, and 16. Young women and ordained young men will be eligible for limited-use temple recommends beginning in January of the year they turn 12. Ordination to a priesthood office for young men and obtaining a limited-use temple recommend for young women and young men will continue to be individual matters, based on worthiness, readiness, and personal circumstances. Ordinations and obtaining limited-use recommends will typically take place throughout January. -

Fear in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and a Pathway to Reconciliation

Fear in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a Pathway to Reconciliation Meandering Philosophy and Musings Mingled with Scripture Revision B By Tom Irvine Email: [email protected] July 4, 2020 To fear God is to have absolute reverence and awe for an Almighty God, the Creator of all things. But the fear discussed in this paper is worry and dread over potential loss or calamity. This fear can include angst regarding a pending change, even though that change may be a needed growth opportunity, or otherwise bring blessings. The fear may be deeply rooted in a person’s subconscious due to genetic predispositions or past traumatic experiences. Furthermore, fear can exist on an individual or an institutional basis. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has accomplished an immeasurable amount of good for innumerable souls by providing a faith community for like-minded people, offering disaster relief to those in distress and in so many other ways. In addition, the LDS Church provides excellent education opportunities through its BYU campuses and the BYU Pathway program. 1 But the Church has traumatized others via certain fear-based policies and unrighteous dominion. Some trauma victims leave the Church and may never return. Others are the “walking wounded” who still participate in Church for social or altruistic reasons even though their bubbles have burst, or their “shelves” have broken. This paper is neither a vindication of the Church nor an expose. Rather it is a paper that wrestles with some real and messy issues with the hopes that some mutual understanding and peaceful reconciliation can be achieved. -

Of Men and Ministry.Indd

OF MEN AND MINISTRY The discipline of service is to make continuous efforts, week by week, to bring others nearer to Christ through His church. BUILDING THE KINGDOM, ONE MAN AT A TIME MEN FROM DALLAS EPISCOPAL CHURCHES HAVE BUILT 14 CONSECUTIVE HABITAT FOR HUMANITY HOUSES OF MEN AND MINISTRY Building God’s Kingdom, one Men are learning man at a time to minister to vets By Jim Goodson The 78th General Conven on resolved to encourage and support dioceses and con Veteran Friendly Congrega ons are easy to start and can have a grega ons in their eff orts to develop and major, las ng impact on both veterans and congrega ons that honor expand ministry to men them. throughout the Episcopal The Veteran Friendly Congrega on concept was created at The Church and to mentor and Episcopal Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Marie a, Georgia, where raise up the next genera Fr. Certain was rector. on of young men through Sixtysix of the na on’s 84 out the Episcopal Church. VFCs are in Georgia. VETERAN The Brotherhood of Others are in Tennessee (12) FRIENDLY St Andrew has been a and one each in Texas, Arizona, CONGREGATIONS leader in men’s ministry South Carolina, Louisiana, California and Florida. VFCs are in the Episcopal / Anglican Jack Hanstein in Episcopal (26), Catholic (13), Church for more than 135 Lutheran (11), Nondenomina onal (10), Bap st (8), Presbyterian (7), years. We have been build Methodist (6), AME (2) and Jewish (1) congrega ons, according to the ing Chris an fellowship Care For The Troops website. -

November 2008 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • NOVEMBER 2008 General Conference Addresses Five New Temples Announced COURTESY OF HOPE GALLERY Christ Teaching Mary and Martha, by Anton Dorph The Savior “entered into a certain village: and a certain woman named Martha received him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, which also sat at Jesus’ feet, and heard his word” (Luke 10:38–39). NOVEMBER 2008 • VOLUME 38 • NUMBER 11 2 Conference Summary for the 178th SUNDAY MORNING SESSION 100 Testimony as a Process Semiannual General Conference 68 Our Hearts Knit as One Elder Carlos A. Godoy President Henry B. Eyring 102 “Hope Ya Know, We Had SATURDAY MORNING SESSION 72 Christian Courage: The Price a Hard Time” 4 Welcome to Conference of Discipleship Elder Quentin L. Cook President Thomas S. Monson Elder Robert D. Hales 106 Until We Meet Again 7 Let Him Do It with Simplicity 75 God Loves and Helps All President Thomas S. Monson Elder L. Tom Perry of His Children 10 Go Ye Therefore Bishop Keith B. McMullin GENERAL RELIEF SOCIETY MEETING Silvia H. Allred 78 A Return to Virtue 108 Fulfilling the Purpose 13 You Know Enough Elaine S. Dalton of Relief Society Elder Neil L. Andersen 81 The Truth of God Shall Go Forth Julie B. Beck 15 Because My Father Read the Elder M. Russell Ballard 112 Holy Temples, Sacred Covenants Book of Mormon 84 Finding Joy in the Journey Silvia H. Allred Elder Marcos A. Aidukaitis President Thomas S. Monson 114 Now Let Us Rejoice 17 Sacrament Meeting and the Barbara Thompson Sacrament SUNDAY AFTERNOON SESSION 117 Happiness, Your Heritage Elder Dallin H. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996

Journal of Mormon History Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 1 1996 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1996) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol22/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --The Emergence of Mormon Power since 1945 Mario S. De Pillis, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --The Mormon Nation and the American Empire D. W. Meinig, 33 • --Labor and the Construction of the Logan Temple, 1877-84 Noel A. Carmack, 52 • --From Men to Boys: LDS Aaronic Priesthood Offices, 1829-1996 William G. Hartley, 80 • --Ernest L. Wilkinson and the Office of Church Commissioner of Education Gary James Bergera, 137 • --Fanny Alger Smith Custer: Mormonism's First Plural Wife? Todd Compton, 174 REVIEWS --James B. Allen, Jessie L. Embry, Kahlile B. Mehr. Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894-1994 Raymonds. Wright, 208 --S. Kent Brown, Donald Q. Cannon, Richard H.Jackson, eds. Historical Atlas of Mormonism Lowell C. "Ben"Bennion, 212 --Spencer J. Palmer and Shirley H. -

Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2009 Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Travis Q. Mecham Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Mecham, Travis Q., "Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints" (2009). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 376. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/376 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANGES IN SENIORITY TO THE QUORUM OF THE TWELVE APOSTLES OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS by Travis Q. Mecham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: _______________________ _______________________ Philip Barlow Robert Parson Major Professor Committee Member _______________________ _______________________ David Lewis Byron Burnham Committee Member Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2009 ii © 2009 Travis Mecham. All rights reserved. iii ABSTRACT Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by Travis Mecham, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2009 Major Professor: Dr. Philip Barlow Department: History A charismatically created organization works to tear down the routine and the norm of everyday society, replacing them with new institutions. -

Lds.Org and in the Questions and Answers Below

A New Balance between Gospel Instruction in the Home and in the Church Enclosure to the First Presidency letter dated October 6, 2018 The Council of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles has approved a significant step in achieving a new balance between gospel instruction in the home and in the Church. Purposes and blessings associated with this and other recent changes include the following: Deepening conversion to Heavenly Father and the Lord Jesus Christ and strengthening faith in Them. Strengthening individuals and families through home-centered, Church-supported curriculum that contributes to joyful gospel living. Honoring the Sabbath day, with a focus on the ordinance of the sacrament. Helping all of Heavenly Father’s children on both sides of the veil through missionary work and receiving ordinances and covenants and the blessings of the temple. Beginning in January 2019, the Sunday schedule followed throughout the Church will include a 60-minute sacrament meeting, and after a 10-minute transition, a 50-minute class period. Sunday Schedule Beginning January 2019 60 minutes Sacrament meeting 10 minutes Transition to classes 50 minutes Classes for adults Classes for youth Primary The 50-minute class period for youth and adults will alternate each Sunday according to the following schedule: First and third Sundays: Sunday School. Second and fourth Sundays: Priesthood quorums, Relief Society, and Young Women. Fifth Sundays: youth and adult meetings under the direction of the bishop. The bishop determines the subject to be taught, the teacher or teachers (usually members of the ward or stake), and whether youth and adults, men and women, young men and young women meet separately or combined. -

Capitol Hill Master Plan Called for Street Street

CAPITOL HILL Marmalade Hill Center this plan. cally and architecturally important districts and resources OVERVIEW as well as the quality of life inherent in historic areas. Ensure new construction is compatible with the historic district within which it is located. Purpose • Enhance the visual and aesthetic qualities of the communi- This is an updated community master plan which replaces ty by implementing historic preservation principles, he Capitol Hill Community is one of Salt Lake the 1981 Capitol Hill Community Master Plan and is the designing public facilities to enhance the established resi- City's eight planning areas. It is generally bounded land use policy document for the Capitol Hill Community. dential character of the Capitol Hill Community and by the Central Business District (North Temple) on However, the 1981 plan will be retained as a valuable sup- encouraging private property improvements that are visual- T the south; Interstate-15 on the west; the north City plemental resource of additional information relating to the ly compatible with the surrounding neighborhood. limits on the north; and City Creek Canyon on the east. community. Land Use, Historic Preservation, Urban Design, • Provide for safe, convenient circulation patterns for vehic- Transportation and Circulation, Environment and Public ular and non-vehicular traffic movement, while discourag- Facilities are all elements of planning reevaluated with ing commuter and commercial traffic on residential streets regard to established formulated goals and policies. This and restricting industrial traffic to appropriate routes. plan should be consulted in conjunction with other city-wide • Ensure adequate community parking while mitigating master plans and strategic plans as they relate to the Capitol adverse effects of parking that comes from outside the Hill Community. -

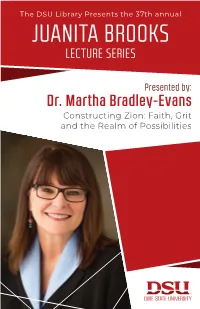

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

One Side by Himself: the Life and Times of Lewis Barney, 1808-1894

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2001 One Side by Himself: The Life and Times of Lewis Barney, 1808-1894 Ronald O. Barney Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Barney, R. O. (2001). One side by himself: The life and times of Lewis Barney, 1808-1894. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Side by Himself One Side by Himself The Life and Times of Lewis Barney, 1808–1894 by Ronald O. Barney Utah State University Press Logan, UT Copyright © 2001 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper 654321 010203040506 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Barney, Ronald O., 1949– One side by himself : the life and times of Lewis Barney, 1808–1894 / Ronald O. Barney. p.cm. — (Western experience series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87421-428-9 (cloth) — ISBN 0-87421-427-0 (pbk.) 1. Mormon pioneers—West (U.S.)—Biography. 2. Mormon pioneers—Utah— Biography. 3. Frontier and pioneer life—West (U.S.). 4. Frontier and pioneer life—Utah. 5. Mormon Church—History—19th century. 6. West (U.S.)—Biography. 7. Utah— Biography.