Organizational Change and Development Chapter 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manager Cascade, Edit, Or Discontinue Goal(S) in Workday

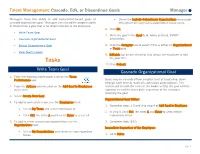

Talent Management: Cascade, Edit, or Discontinue Goals Manager Managers have the ability to add department-based goals or • Check the Include Subordinate Organizations to cascade cascade organization goal. Managers can also edit in-progress goals throughout all supervisory organization below yours. or discontinue a goal that is no longer relevant to the employee. 6. Click OK. • Write Team Goal 7. Write the goal in the Goal field. Add a detailed, SMART • Cascade Organizational Goal description. • Edit or Discontinue a Goal 8. Click the Category box to select if this is either an Organizational or Team goal. • View Team’s Goals 9. Editable will be pre-selected. This allows the employee to edit Tasks the goal title. 10. Click Submit. Write Team Goal Cascade Organizational Goal 1. From the Workday home page, click on the Team Performance app. Goals may be cascaded from a higher level of leadership, down through each level to reach all supervisory organizations. This 2. From the Actions column, click on the Add Goal to Employees section will include the steps of the leader writing the goal and the menu item. approval step of the immediate supervisor of the employee receiving the goal. 3. Select Create New Goal. Organizational Goal Writer: 4. To add to immediate team, use the Employees field: 1. Complete steps 1-3 and skip step 4 of Add Goal to Employee. • Select My Team and select individuals or 2. In step 5, click Ctrl, the letter A and Enter to select entire • Click Ctrl, the letter A and then hit Enter to select all. -

Chapter 6 – Group and Team Performance 90

Chapter 6 – Group and Team Performance 90 CHAPTER 6 – Group and Team Performance OBJECTIVES The major purpose of this chapter on group process and effectiveness is to introduce the student to ways to think about interacting groups so that they will become more effective members and leaders of them. Every student has had some experience with both social and task groups that they can call on as they study this topic. Our first objective in this chapter is to focus on how central these groups are to our lives. We also attempt to impress on the students that they will likely spend large proportions of their work hours in small group settings, because modern management appears to be making increasing use of teams or other small groups to solve problems, make decisions, and execute tasks. The next objective is to help student understand the many types of groups they may be involved with and how groups vary by purpose and organization. Another objective is to introduce students to a basic model of group effectiveness that includes influences from the environment within which the group operates. Environmental influences can have a critical impact on group effectiveness and the different types of influences are considered. At this point the chapter changes its focus to give more emphasis to internal group dynamics by covering such topics as cooperation and competition. Here, one objective is to introduce students to group development and the process by which groups become (or fail to become) mature. Another objective is to introduce the role of norms in influencing group member behavior. -

The View from the Top Mark Cuban Talks Adapting to a COVID-19 World, Diversity and Inclusion, and More

An Equilar publication Issue 34, Fall 2020 The View From the Top Mark Cuban talks adapting to a COVID-19 world, diversity and inclusion, and more FEATURING CEO Pay by U.S. President & Interview with Shellye Archambeau Issue 34 Critical governance issues post-pandemic The rising role of General Counsel Fall 2020 Demystifying data science for board members Setting incentives in uncertain times How CEO pay ratios affect Say on Pay Executive equity awards and the pandemic 36 ASK THE EXPERTS commentary on current topics Lessons Learned What will be the most critical governance issues companies must address post-pandemic? golibtolibov/gettyimages.com 37 Navigating the COVID-19 pandemic has created profound and unique ROBERT BARBETTI challenges for public and private companies. But it’s also an opportunity to Global Head of Executive solidify current corporate governance and create important new policies. Compensation and Benefits Boards and senior management should consider the following as part of good J.P. MORGAN corporate governance, not only in the context of an unprecedented global PRIVATE BANK pandemic, but in any business environment. Ensure communication systems are solid. Understanding the impact COVID-19 has on business operations and suppliers is critical, but Robert Barbetti, Managing Director, is the communicating that understanding to teams is just as important. There are Global Head of Executive Compensation now many new federal and state regulations in place that must be considered and Benefits at J.P. Morgan Private as companies create their policies to mitigate risk and stay compliant. Bank. As a senior member of the Private Management should stay abreast of updated crisis policies, disaster Bank’s Advice Lab, Mr. -

Organizational Behavior Management in Health Care: Applications for Large-Scale Improvements in Patient Safety

Organizational Behavior Management in Health Care: Applications for Large-Scale Improvements in Patient Safety Thomas R. Cunningham, MS, and E. Scott Geller, PhD Abstract Medical errors continue to be a major public health issue. This paper attempts to bridge a possible disconnect between behavioral science and the management of medical care. Epidemiologic data on patient safety and a sampling of current efforts aimed at patient safety improvement are provided to inform relevant applications of organizational behavior management (OBM). The basic principles of OBM are presented, along with recent innovations in the field that are relevant to improving patient safety. Safety-related applications of behavior- based interventions from both the behavioral and medical literature are critically reviewed. Potential OBM targets in health care settings are integrated within a framework of those OBM techniques with the greatest possibility of improving patient safety on a large scale. Introduction Organizational behavior management (OBM) focuses on what people do, analyzes why they do it, and then applies an evidence-based intervention strategy to improve what people do. The relevance of OBM to improving health care is obvious. While poorly designed systems contribute to most medical errors, OBM provides a practical approach for addressing a critical component of every imperfect health care system—behavior. Behavior is influenced by the system in which it occurs, yet it can be treated as a unique contributor to many medical errors, and certain changes in behavior can prevent medical error. This paper reviews the principles and procedures of OBM as they relate to reducing medical error and improving health care. -

Planning for Organization Development in Operations Control Centers

Federal Aviation Administration DOT/FAA/AM-12/6 Office of Aerospace Medicine Washington, DC 20591 Planning for Organization Development in Operations Control Centers Linda G. Pierce Clara A. Williams Cristina L. Byrne Darendia McCauley Civil Aerospace Medical Institute Federal Aviation Administration Oklahoma City, OK 73125 June 2012 Final Report OK-12-0025-JAH NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents thereof. ___________ This publication and all Office of Aerospace Medicine technical reports are available in full-text from the Civil Aerospace Medical Institute’s publications Web site: www.faa.gov/library/reports/medical/oamtechreports Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT/FAA/AM-12/6 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Planning for Organization Development in Operations Control Centers June 2012 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Pierce LG, Williams CA, Byrne CL, McCauley D 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute P.O. Box 25082 11. Contract or Grant No. Oklahoma City, OK 73125 12. Sponsoring Agency name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of Aerospace Medicine Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Ave., S.W. Washington, DC 20591 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplemental Notes Work was accomplished under approved task AM-B-11-HRR-523 16. Abstract The first step in a proposed program of organization development (OD) was to assess organizational processes within the Technical Operations Services (TechOps) Operations Control Centers (OCCs). -

Shared Leadership Underpinning of the MLCF

Shared Leadership Underpinning of the MLCF A key product from the Enhancing Engagement in Medical Leadership project has been the development of a Medical Leadership Competency Framework (MLCF). This document defines the skills and competences needed by doctors to engage effectively in the planning, provision and improvement of health care services. It applies to all doctors and is intended to be acquired across the medical career at each appropriate level (Undergraduate, Postgraduate and Continuing Practice). It is therefore not aimed at specific, positional leaders but is seen as a set of competences that should be fully integrated into the medical role and not a separate function. The philosophical leadership model that underpins this approach is that of shared leadership, a more modern conception of leadership that departs from traditional charismatic or hierarchical models. In working with the MLCF it is useful to understand the shared leadership approach and this paper is an attempt to provide a simple description and guide to the shared leadership model, and to answer some of the questions about shared leadership that have been asked during the development of the MLCF: • What is shared leadership? • How does shared leadership underpin the MLCF? • How does shared leadership relate to positional leadership? • Where is the evidence that shared leadership works and what can we learn from other settings? • What evidence is there from health care and how do we apply shared leadership in a clinical setting? • What do the critics of shared leadership say? What is shared leadership? Leadership in any context has historically been described in relation to the behaviour of an individual and their relationship to their followers. -

Exploring the Conceptual Expansion Within the Field of Organizational Behavior: Organizational Climate and Organizational Culture

Exploring the conceptual expansion within the field of organizational behavior: Organizational climate and organizational culture. Willem Verbeke, Marco Volgering, and Marco Hessels Erasmus University Rotterdam Abstract Developments within social and exact sciences take place because scientists engage in scientific practices that allow them to further expand and refine the scientific concepts within their scientific disciplines. There is disagreement among scientists as to what the essential practices are that allow scientific concepts within a scientific discipline to expand and evolve. One group looks at conceptual expansion as something that is being constrained by rational practices. Another group however suggests that conceptual expansion proceeds along the lines of ‘everything goes.’The goal of this paper is to test whether scientific concepts expand in a rational way within the field of organizational behavior. We will use organizational climate and culture as examples. The essence of this study consists of two core concepts: one within organizational climate and one within organizational culture. It appears that several conceptual variations are added around these core concepts. The variations are constrained by rational scientific practices. In other terms, there is evidence that the field of organizational behavior develops rationally. 1. Introduction In every scientific discipline scholars come to ask what the researchers in their field have been doing, what the focus of research should be and/or where their research field is or should be heading to. These kind of questions are also being asked in the field of organizational behavior by scholars like Schneider (1985), Dunnette (1991) and O'Reilly (1991). From a theoretical point of view, these scholars question what and how scientific concepts--like emotions, organizational environment, performance etc.--could be used in order to answer the more fundamental question within their discipline: “i.e. -

Team Leadership Styles

Team Leadership Styles Leadership Skills Team FME www.free-management-ebooks.com ISBN 978-1-62620-988-6 Copyright Notice © www.free-management-ebooks.com 2013. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-62620-988-6 The material contained within this electronic publication is protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and treaties, and as such any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is strictly prohibited. You may not copy, forward, or transfer this publication or any part of it, whether in elec- tronic or printed form, to another person, or entity. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the permission of the copy- right holder is against the law. Your downloading and use of this eBook requires, and is an indication of, your complete acceptance of these ‘Terms of Use.’ You do not have any right to resell or give away part, or the whole, of this eBook. TEAM LEADERSHIP STYLES Table of Contents Preface 2 Visit Our Website 3 Introduction 4 Team Examples 6 Development Team Example 7 Customer Support Team Example 9 Steering Team Example 10 Leadership Theories 13 Early Trait Theories 13 Leadership for Management 16 Transactional Leadership 17 Applied to the Team Examples 19 Transformational Leadership 22 Applied to the Team Examples 24 Situational Leadership® 26 Applied to the Team Examples 28 The Leadership Continuum 30 Applying this Style to the Team Examples 32 Summary 34 Other Free Resources 35 References 36 ISBN 978-1-62620-988-6 © www.free-management-ebooks.com 1 TEAM LEADERSHIP STYLES Preface This eBook has been written for managers who find themselves in a team leadership role. -

Customer Relationship Management, Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact on Customer Loyalty

Customer Relationship Management, Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact on Customer Loyalty Sulaiman, Said Musnadi Faculty of Economic and Business, University of Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia Keywords: Customer Relationship Management, Satisfaction, Customer Loyalty. Abstract: This study aims to determine the effect of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) on Customer Satisfaction and its impact on Customer Loyalty of Islamic Bank in Aceh’s Province. The study population is all customers in in the Islamic Bank. This study uses convinience random sampling with a sample size of 250 respondents. The analytical method used is structural equation modeling (SEM). The results showed that the Customer Relationship Management significantly influences both on satisfaction and its customer loyalty. Furthermore, satisfaction also affects its customer loyalty. Customer satisfaction plays a role as partially mediator between the influences of Customer Relationship Management on its Customer Loyalty. The implications of this research, the management of Islamic Bank needs to improve its Customer Relationship Management program that can increase its customer loyalty. 1 INTRODUCTION small number of studies on customer loyalty in the bank, as a result of understanding about the loyalty 1.1 Background and satisfaction of Islamic bank’s customers is still confusing, and there is a very limited clarification The phenomenon underlying this study is the low about Customer Relationship Management (CRM) as a good influence on customer satisfaction and its -

An Exploration of Organizational Buying Behavior in the Public Sector

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Marketing and Supply Chain Marketing & Supply Chain 2018 AN EXPLORATION OF ORGANIZATIONAL BUYING BEHAVIOR IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR Kevin S. Chase University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.119 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Chase, Kevin S., "AN EXPLORATION OF ORGANIZATIONAL BUYING BEHAVIOR IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Marketing and Supply Chain. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/marketing_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Marketing & Supply Chain at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Marketing and Supply Chain by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Performance Management at R&D Organizations

MTR090189 MITRE TECHNICAL REPORT Performance Management at R&D Organizations Practices and Metrics from Case Examples Carolyn Kahn Sheila McGourty In support of: • FY 2009 Sponsor Performance Management Investigations (POCs: K. Buck and M. Steinbach) • FY 2009 CEM Stakeholder-Driven Performance Management MOIE (POCs: L. Oakley-Bogdewic and K. Buck) April 2009 This page intentionally left blank. MTR090189 MITRE TECHNICAL REPORT Performance Management at R&D Organizations Practices and Metrics from Case Examples Dept. No.: E520 Carolyn Kahn Project No.: 1909M140-AA Sheila McGourty The views, opinions and/or findings contained in this report are those of The In support of: MITRE Corporation and should not be construed as an official government position, • FY 2009 Sponsor Performance Management policy, or decision, unless designated by Investigations (POCs: K. Buck and M. Steinbach) other documentation. • FY 2009 CEM Stakeholder-Driven Performance Approved for public release; Management MOIE (POCs: L. Oakley-Bogdewic and distribution unlimited. K. Buck) Case #09-2188 ©2009 The MITRE Corporation. April 2009 All Rights Reserved. 3 Abstract Performance management supports and enables achievement of an organization and/or program's strategic objectives. It connects activities to stakeholder and mission needs. Effective performance management focuses an organization or program to achieve optimal value from the resources that are allocated to achieving its objectives. It can be used to communicate management efficiencies and to show transparency of goal alignment and resource targeting, output effectiveness, and overall value of agency outcomes or progress toward those outcomes. This paper investigates performance management from the perspective of research and development (R&D) organizations and programs. -

Experimenting Team-Building Strategies in an Innovative Nexus Learning Capstone Course

Experimenting Team-Building Strategies in an Innovative Nexus Learning Capstone Course Gulbin Ozcan-Deniz, Ph.D, LEED AP BD+C, [email protected] Assistant Professor, College of Architecture and the Built Environment, Philadelphia University, Philadelphia, PA Agenda Motivation and Primary Goals Re-design Steps of Capstone Sample Team-building Activities Problem-solving in a Team Student Assessment Results Digital Tools for Collaboration Conclusions Motivation and Primary Goals Research Primary Goals Motivation the need for a experiment with stimulate peer and collaborative team-building and team-based capstone course in collaborative learning many disciplines working problems Ozcan Deniz, G. (2016), Innovative Nexus Learning Capstone Experience for Construction Management Students, Philadelphia University Nexus Learning Grant Proposal, 2016-2017. Motivation and Primary Goals Specific Project Goals To understand the background, To determine the characteristics, To determine which impact of collaborative processes, and digital tools enables learning on preparing dynamics that collaboration within and presenting an contribute to team- teams actual bid package to working and team- external parties success in construction Re-design Steps of Capstone Revise learning outcomes Design an active Create an hybrid teaching database of course delivery team-building and module by using team-work activities Blackboard Prepare start-of-semester, mid- Run the revised course semester and end-semester Analyze survey results with a group of pilot surveys to analyze team- and update course students and collect building and collaborative material as needed feedback working problems faced by Capstone students Sample Team-building Activities 3-truths and a lie Which team player style are you? Contributor Challenger Collaborator Communicator Parker, G.M.