1 I. Introduction Interest Rates, Financial Leverage, and Asset Values Are

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Valuation of Apartments

THE VALUATION OF APARTMENTS By Tim Klein & Dan Blonigen Goals of this course Introduction to the basic concepts of Apartment Valuation You will leave with the ability to value an apartment in your jurisdiction! Outline What is an apartment The Inspection Valuation Sales Verification & Comparison Income Capitalization Mass Appraisal Techniques Case Study Q & A Current Market 32% of US Households are Renters – NMHC 30% of Apartment renters are under age 30, 58% under age 44 -NMHC Represents 38% of new housing starts – US Census, May 2014 “Minneapolis-St. Paul, one of the strongest rental markets in the nation.” – Marcus Millichap 2014 4th in the Nation – Marcus Millichap Cap Rates National Korpacz 1Q ’13: Average 5.73% Korpacz 1Q ’14: Average 5.79% Minneapolis RERC 1Q ‘13: Average 6.0% Consumer Life Cycle What is an Apartment What is an Apartment An Apartment is a housing unit of one or more rooms, designed to provide complete living facilities for one or more occupants. An Apartment Building is a structure containing four or more dwelling units with common areas and facilities. Common Area includes entrances, lobby, elevators or stairs, mechanical space, grounds, pool, etc… Apt Styles– Low Rise Typically 1 -3 stories No elevators 12-50 units Intermediate density Apt Styles– Mid Rise Usually steel or reinforced concrete 4-10 stories Elevator service Intermediate density Apt Styles– High Rise Steel or reinforced concrete More than 10 stories Elevator service High density Usually in urban core Apt Styles– -

Down Payment and Closing Cost Assistance

STATE HOUSING FINANCE AGENCIES Down Payment and Closing Cost Assistance OVERVIEW STRUCTURE For many low- and moderate-income people, the The structure of down payment assistance programs most significant barrier to homeownership is the down varies by state with some programs offering fully payment and closing costs associated with getting a amortizing, repayable second mortgages, while other mortgage loan. For that reason, most HFAs offer some programs offer deferred payment and/or forgivable form of down payment and closing cost assistance second mortgages, and still other programs offer grant (DPA) to eligible low- and moderate-income home- funds with no repayment requirement. buyers in their states. The vast majority of HFA down payment assistance programs must be used in combi DPA SECOND MORTGAGES (AMORTIZING) nation with a first-lien mortgage product offered by the A second mortgage loan is subordinate to the first HFA. A few states offer stand-alone down payment and mortgage and is used to cover down payment and closing cost assistance that borrowers can combine closing costs. It is repayable over a given term. The with any non-HFA eligible mortgage product. Some interest rates and terms of the loans vary by state. DPA programs are targeted toward specific popula In some programs, the interest rate on the second tions, such as first-time homebuyers, active military mortgage matches that of the first mortgage. Other personnel and veterans, or teachers. Others offer programs offer more deeply subsidized rates on their assistance for any homebuyer who meets the income second mortgage down payment assistance. Some and purchase price limitations of their programs. -

Commercial Mortgage Loans

STRATEGY INSIGHTS MAY 2014 Commercial Mortgage Loans: A Mature Asset Offering Yield Potential and IG Credit Quality by Jack Maher, Managing Director, Head of Private Real Estate Mark Hopkins, CFA, Vice President, Senior Research Analyst Commercial mortgage loans (CMLs) have emerged as a desirable option within a well-diversified fixed income portfolio for their ability to provide incremental yield while maintaining the portfolio’s credit quality. CMLs are privately negotiated debt instruments and do not carry risk ratings commonly associated with public bonds. However, our paper attempts to document that CMLs generally available to institutional investors have a credit profile similar to that of an A-rated corporate bond, while also historically providing an additional 100 bps in yield over A-rated industrials. CMLs differ from public securities such as corporate bonds in the types of protections they offer investors, most notably the mortgage itself, a benefit that affords lenders significant leverage in the relationship with borrowers. The mortgage is backed by a hard, tangible asset – a property – that helps lenders see very clearly the collateral behind their investment. The mortgage, along with other protections, has helped generate historical recovery from defaulted CMLs that is significantly higher than recovery from defaulted corporate bonds. The private CML market also provides greater flexibility for lenders and borrowers to structure mortgages that meet specific needs such as maturity, loan amount, interest terms and amortization. Real estate as an asset class has become more popular among institutional investors such as pension funds, insurance companies, open-end funds and foreign investors. These investors, along with public real estate investment trusts (REITs), generally invest in higher quality properties with lower leverage. -

Commercial Invest Real Estate September-October

How do investors determine ROI in an unsteady market? byy Eric B. Garfi eld,, MAI, MRICS,, and Matthew T. VanEck capitalization rate is the overall or non- As a reminder, it is noteworthy that cap ers commonly were using physical residual financed return on a real estate invest- rates and discount rates, or internal rates techniques such as land and buildings. In ment, akin to the return on total assets in of return, are not mutually exclusive. A 1959, Ellwood published “Ellwood Tables accounting terms. A cap rate is calculated discount rate is a measure of investment for Real Estate Appraising and Financing,” as a mathematical relationship between net performance over a holding period that which showed that by analyzing market operating income and an asset’s value. Most accounts for risk and return on capital. Cap mortgage terms and equity yields for a par- commonly cap rates are extracted from rates not only account for return on capital, ticular property, an appraiser could identify transactions of buyers and sellers compet- but also return of capital. A discount rate a suitable cap rate and thus property value. ing in a marketplace; but they are related to can be built up from a cap rate if income and This valuation technique became known the current state of capital markets as well growth both change at a constant rate. The as mortgage-equity analysis. Ellwood’s as the future growth outlook. So how can buildup is derived by the formula Y = R + method allowed appraisers to incorporate real estate professionals extract cap rates in CR, where Y = discount (yield) rate, R = cap and explain fi nancing’s impact on value. -

Real Estate Market Fundamentals and Asset Pricing

Real Estate Market Fundamentals and Asset Pricing Petros S. Sivitanides, Raymond G. Torto, and William C. Wheaton n the last year we have heard much discussion of a disconnect between the commercial real estate cap- ital and space markets. We see declines in the cap rates (yields) of property transactions, while a weak- Iened economy has generated deteriorating real estate market fundamentals (Gordon [2003]; Kaiser [2003]). Corcoran and Iwai [2003] argue that such a pattern could be just what an efficient asset market should pro- duce if the space market is always mean-reverting. If fundamentals are temporarily depressed, an efficient mar- ket will keep prices firm and hence produce lower cap rates—in anticipation of a recovery. If the space market is strong, cap rates should fall in anticipation of eventual new supply and market softening. PETROS S. SIVITANIDES is a Our objective in this discussion is an econometric senior economist at Torto examination of the historical movements in office space Wheaton Research in Boston (MA 02110). market fundamentals (vacancy and rental rates) in order psivitanides@ to compare them with a similar history of office market tortowheatonresearch.com capital movements (prices and yields). This comparison supports three conclusions: RAYMOND G. TORTO is a managing director at Torto Wheaton Research in Boston 1. In examining how market fundamentals influ- (MA 02110). ence asset pricing, it is crucial to control for [email protected] interest rates. In fact, a better way to measure how the asset market views the space market is WILLIAM C. WHEATON is a to look at real estate spreads over Treasuries. -

Your Step-By-Step Mortgage Guide

Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide From Application to Closing Table of Contents In this Guide, you will learn about one of the most important steps in the homebuying process — obtaining a mortgage. The materials in this Guide will take you from application to closing and they’ll even address the first months of homeownership to show you the kinds of things you need to do to keep your home. Knowing what to expect will give you the confidence you need to make the best decisions about your home purchase. 1. Overview of the Mortgage Process ...................................................................Page 1 2. Understanding the People and Their Services ...................................................Page 3 3. What You Should Know About Your Mortgage Loan Application .......................Page 5 4. Understanding Your Costs Through Estimates, Disclosures and More ...............Page 8 5. What You Should Know About Your Closing .....................................................Page 11 6. Owning and Keeping Your Home ......................................................................Page 13 7. Glossary of Mortgage Terms .............................................................................Page 15 Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide your financial readiness. Or you can contact a Freddie Mac 1. Overview of the Borrower Help Center or Network which are trusted non- profit intermediaries with HUD-certified counselors on staff Mortgage Process that offer prepurchase homebuyer education as well as financial literacy using tools such as the Freddie Mac CreditSmart® curriculum to help achieve successful and Taking the Right Steps sustainable homeownership. Visit http://myhome.fred- diemac.com/resources/borrowerhelpcenters.html for a to Buy Your New Home directory and more information on their services. Next, Buying a home is an exciting experience, but it can be talk to a loan officer to review your income and expenses, one of the most challenging if you don’t understand which can be used to determine the type and amount of the mortgage process. -

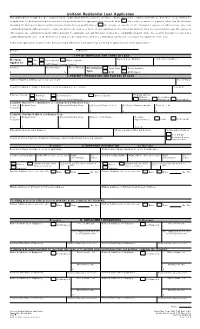

Sample Mortgage Application (PDF)

Uniform Residential Loan Application This application is designed to be completed by the applicant(s) with the Lender's assistance. Applicants should complete this form as "Borrower" or "Co-Borrower," as applicable. Co-Borrower information must also be provided (and the appropriate box checked) when the income or assets of a person other than the Borrower (including the Borrower's spouse) will be used as a basis for loan qualification or the income or assets of the Borrower's spouse or other person who has community property rights pursuant to state law will not be used as a basis for loan qualification, but his or her liabilities must be considered because the spouse or other person has community property rights pursuant to applicable law and Borrower resides in a community property state, the security property is located in a community property state, or the Borrower is relying on other property located in a community property state as a basis for repayment of the loan. If this is an application for joint credit, Borrower and Co-Borrower each agree that we intend to apply for joint credit (sign below): Borrower Co-Borrower I. TYPE OF MORTGAGE AND TERMS OF LOAN Agency Case Number Lender Case Number Mortgage VA Conventional Other (explain): Applied for: FHA USDA/Rural Housing Service Amount Interest Rate No. of Months Amortization Fixed Rate Other (explain): $%Type: GPM ARM (type): II. PROPERTY INFORMATION AND PURPOSE OF LOAN Subject Property Address (street, city, state & ZIP) No. of Units Legal Description of Subject Property (attach description if necessary) Year Built Purpose of Loan Purchase Construction Other (explain): Property will be: Primary Secondary Refinance Construction-Permanent Residence Residence Investment Complete this line if construction or construction-permanent loan. -

Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 on CRE Property Valuations

May 2020 CRE Research Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 on CRE Property Valuations Commercial real estate’s immunity to the COVID-19 • Payment is made in cash or its equivalency pandemic is about to be tested in a multitude of ways. Each of the commercial property sectors: Lodging, Re- • The sales price is not impacted by special or creative tail, Multifamily, Industrial, and Office are going to face financing terms or concessions their own unique set of COVID related challenges. The In summary, market value is representative of a transac- million-dollar question looming for each of the market tion where no exceptional factors influence the parties participants, i.e. owners, brokers, lenders, and apprais- (buyers, sellers, lenders) to the transaction. ers, is straightforward and simple to understand, but not so simple to answer: COVID-19 would be considered an exceptional factor that would influence all parties to a transaction. The market value definitions, nor the additional bullet points above, What is my Property’s Value? provide much clarity or guidance for appraisers to rely on Appraisal of commercial real estate is an interesting en- when appraising a commercial property during this pan- deavor with its share of skeptics, even when the market demic. The concepts of market value as previously de- is stable and operating efficiently. The Uniform Standards fined do not contemplate how short-term occupancy and of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) 2020-2021 revenue declines caused by external forces, beyond the edition defines market value as, “a type of value, stated control of the owner/property manager, should be treated as an opinion, that presumes the transfer of a property by the appraiser. -

Community Land Trust (CLT) FAQ

Community Land Trust (CLT) FAQ Q1: What are CLTs? CLTs are nonprofit organizations created to increase and maintain the supply of affordable housing by providing homeownership opportunities to low- and moderate-income families. Properties are acquired by the CLT and the homes are sold to borrowers using standard mortgage products. The land under the houses is held by the CLT and leased to the homeowners at very low monthly rates. By eliminating the cost of land ownership, this low monthly lease rate helps keep the home affordable in higher cost areas. To date, more than 6,000 CLT properties have been developed across the United States according to the Institute for Community Economics (ICE). Q2: Are there resale restrictions for CLTs? Yes, the lease includes provisions that require the continued use of the land to assist future eligible borrowers. Q3: If the borrower is in default, does the CLT have the right of first refusal to purchase the property? Yes, the terms of the Fannie Mae ground lease rider give the CLT the right to purchase the subject property from the lender prior to foreclosure. Q4: How can I find out more about setting up a CLT? A national organization called the Grounded Solutions Network (formerly the National Community Land Trust Network) provides training resources, technical assistance, and other information to new and existing CLTs. For more information, visit their website: https://groundedsolutions.org/. Q5: What are the requirements for a CLT mortgage to be eligible for sale to Fannie Mae? The lender must confirm that the CLT is a nonprofit organization or public entity, such as a state or local government, county, school district, university, or college. -

FICO Mortgage Credit Risk Managers Handbook

FICO Mortgage Credit Risk Manager’s Best Practices Handbook Craig Focardi Senior Research Director Consumer Lending, TowerGroup September 2009 Executive Summary The mortgage credit and liquidity crisis has triggered a downward spiral of job losses, declining home prices, and rising mortgage delinquencies and foreclosures. The residential mortgage lending industry faces intense pressures. Mortgage servicers must better manage the rising tide of defaults and return financial institutions to profitability while responding quickly to increased internal, regulatory, and investor reporting requirements. These circumstances have moved management of mortgage credit risk from backstage to center stage. The risk management function cuts across the loan origination, collections, and portfolio risk management departments and is now a focus in mortgage servicers’ strategic planning, financial management, and lending operations. The imperative for strategic focus on credit risk management as well as information technology (IT) resource allocation to this function may seem obvious today. However, as recently as June 2007, mortgage lenders continued to originate subprime and other risky mortgages while investing little in new mortgage collections and infrastructure, technology, and training for mortgage portfolio management. Moreover, survey results presented in this Handbook reveal that although many mortgage servicers have increased mortgage collections and loss mitigation staffing, few servicers have invested sufficiently in data management, predictive analytics, scoring and reporting technology to identify the borrowers most at risk, implement appropriate treatments for different customer segments, and reduce mortgage re-defaults and foreclosures. The content of this Handbook is based on a survey that FICO, a leader in decision management, analytics, and scoring, commissioned from TowerGroup, a leading research and advisory firm focusing on the strategic application of technology in financial services. -

Investment Strategy, Vacancy and Cap Rates †

INVESTMENT STRATEGY, VACANCY AND CAP RATES † Eli Beracha Associate Professor of Real Estate Director, Hollo School of Real Estate Florida International University, 1101 Brickell Avenue Suite 1100 S, Miami, FL 33131 305-779-7906 [email protected] David H. Downs Professor, Alfred L. Blake Endowed Chair Director, The Kornblau Institute Kornblau Real Estate Program Virginia Commonwealth University School of Business Richmond, VA 23284-4000 804-475-9125 [email protected] Greg MacKinnon Director of Research Pension Real Estate Association 100 Pearl Street, 13th floor Hartford CT 06103 806-785-3847 [email protected] Abstract In this paper we examine whether and to what extent the vacancy of a commercial real estate property is related to its valuation and investment performance. Using data on individual properties, we find that high- vacancy properties are associated with lower cap rates, which suggests the expectation for higher future NOI growth from the potential occupancy of vacant space. Consistent with these expectations, we also find that, on average, high-vacancy properties are associated with higher future NOI growth compared with low-vacancy properties. On the other hand, we find evidence that the investment performance of high-vacancy properties is inferior to the performance of low-vacancy properties, on average. Overall, these results suggest an overvaluation of vacant space. This version: February 22, 2019 † We thank the Real Estate Research Institute for a research grant. We also thank the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries and CoStar for providing their commercial real estate data. INVESTMENT STRATEGY, VACANCY AND CAP RATES Introduction: The vacant space associated with commercial real estate (CRE) properties can be viewed by investors as an option for additional revenue in the event the vacant space is occupied. -

Nber Working Paper Series Covered Farm Mortgage

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES COVERED FARM MORTGAGE BONDS IN THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY U.S. Kenneth A. Snowden Working Paper 16242 http://www.nber.org/papers/w16242 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2010 This paper has benefited from the comments of Walid BuSaba, Charles Courtemanche, John Neufeld, Dan Rosenbaum, Chris Ruhm, Chris Swann, Insan Tunali, two anonymous referees and participants of seminars at UNC Greensboro, Rutgers and the University of Western Ontario. Nidal Abu Saba assembled the Watkins loan sample while Debra Ritch and Michael Cofer provided invaluable research assistance in coding Watkins’s mortgage ledgers. The material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Grant No. SES-9122566. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by Kenneth A. Snowden. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Covered Farm Mortgage Bonds in the Late Nineteenth Century U.S. Kenneth A. Snowden NBER Working Paper No. 16242 July 2010 JEL No. G28,G29,N1,N11,N2,N21,N5,N51,R51 ABSTRACT Covered mortgage bonds have been used successfully in Europe for two centuries, but failed in the U.S.