Lady Llanover and the Creation of a Welsh Cultural Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C ANGELL, Glandwr Street, Gl

No Redg Chassis Chasstype Body Seats Orig Redg Date Status Operator Livery Location CSANGABER "C ANGELL, Glandwr Street, Glandwr Industrial Estate, Aberbeeg, Blaenau Gwent (0,5,0) FN: C & R Transport PG7402/I G200 RRN Vo B10M-60 020302 VH 13917 C49F G501 CJT Feb-08 J222 CNR Vo B10M-60028692 Pn 9112VCP0492 C48FT J701 CWT Sep-07 H 11 CNR MB 811D 670303-2P-082331 RB C33F 18471 J764 ONK Jun-06 M111 CNR MB 711D WDB6693632N030899 Onyx C24F M 20 TGC N111 CNR MB 814D 670313-2N-027798 Pn C33F 958.5MMY3616 N 98 BHL Aug-05 N125 FFV Fd Tt SFAEXXBDVESS30782 Fd M8 Mar-03 N213 TAX Fd Tt P111 CNR MB 711D R111 CNR Fd Tt WF0EXXGBFE2B39351 Ford M16 WN52 XTO Jun-06 T726 SCN Fd Tt Y162 GBO Fd Tt CSBENGRIF JSB & KE BENNING, 13 East View, GRIFFITHSTOWN, NP4 5DW PG6666/N (0,2,2) FN: B's Travel OC: Unit 18, The Old Cold Stores, Court Road Industrial Estate, Cwmbran, Torfaen, NP44 H315 TWE Mercedes 811D WDB6703032P020867 Ce C16.108 B32F Mar-07 sale 2/08 R222 BST LDV Cy X222 BST MB 311D BU56 AZW Ibs 45C14 ZCFC45A100D315479 Excel 664 M16 Oct-06 CSBOYDNEW "MB CHICK, ISCA Works, Mill Parade, NEWPORT, NP20 2JQ" (0,8,12) FN: Croydon Minibus Hire PG6750/N DXI 84 Scania K113T Irizar C FT P 26 RGO Feb-05 JUI 1716 Vo B10M-53 16728 VH C49FT 13500 (E280HRY) Sep-00 TIL 7205 Kassbohrer S215HD WKK17900001035026 Setra C49FT APA 672Y Jan-07 YAZ 6392 MB 811D 670303-20-815779 Oe C29F 311 (E872EHK/MXX481/E872EHK)Apr-06 A 7 FRX Sca K93CRB 1818346 Pn C53F 9012SFA2221 (H524DVM) Mar-06 sale 4/07 A 8 FRX Sca K93CRB 1818350 Pn 9012SFA2225 C53F (H528DVM) Mar-06 w G 57 KTG Oe MR09 VN2020 -

Introduction to the Pack

INTRODUCTION TO THE PACK Wales Millennium Centre will be a landmark centre for the performing arts staging musicals, opera, ballet and dance. International festivals, workshops, tours and visiting art exhibitions will take place against the background of a mixed retail setting. When the Centre opens in 2004 on Cardiff Bay waterfront it will stand alongside the most culturally outstanding arts venues in Europe. The building makes a strong cultural statement for Wales and demonstrates the nation’s new-found confidence as a player in Europe and on a world stage. The design concepts are inspired by the landscape and industrial heritage of Wales – the layered strata of sea cliffs – the multi-coloured slate of North Wales - the texture and colour of steel, and the simple beauty of Welsh hardwoods. Wales Millennium Centre will be a landmark building and will become a national icon. Aim of education pack To utilise the exciting opportunity of the construction of the Wales Millennium Centre to develop resources to enhance educational provision in Wales and ensure that all our young people, their teachers and parents are aware of the arrival of this unique international arts centre in Cardiff Bay. Concept A “think tank” was organised in November 2001, involving teachers and education advisers from all over Wales with the architects and WMC personnel responsible for the construction of the Centre. The group agreed on two guiding principles: • The product should consist of a box of exciting resources, supported by suggested activities for teachers to use with a wide range of pupils. The suggestions would be provided to stimulate further activity and not meant to be in any way prescriptive. -

Cyngor Sir Fynwy/ Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol

Cyngor Sir Fynwy/ Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol Ceisiadau Cynllunio a Benderfynwyd/ Weekly List of Determined Planning Applications Wythnos / Week 18.03.21 i/to 24.03.21 Dyddiad Argraffu / Print Date 25.03.2021 Mae’r Cyngor yn croesawu gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg, Saesneg neu yn y ddwy iaith. Byddwn yn cyfathrebu â chi yn ôl eich dewis. Ni fydd gohebu yn Gymraeg yn arwain at oedi. The Council welcomes correspondence in English or Welsh or both, and will respond to you according to your preference. Corresponding in Welsh will not lead to delay. Ward/ Ward Rhif Cais/ Disgrifia d o'r Cyfeiriad Safle/ Penderfyniad/ Dyddiad y Lefel Penderfyniad/ Application Datblygiad/ Site Address Decision Penderfyniad/ Decision Level Number Development Decision Date Description Llantilio DM/2021/00007 A portal steel frame with The Croft Farm Barn Acceptable 24.03.2021 Delegated Officer Crossenny box profile exterior, Whitecastle Road concrete floor a Llanvetherine Plwyf/ Parish: pedestrian door 2 roller Abergavenny Llantilio shutter doors. Monmouthshire Crossenny NP7 8RA Community Council Llantilio DM/2021/00063 Proposed single storey Brynawelon Approve 22.03.2021 Delegated Officer Crossenny extension. Tre-adam Lane Llantilio Crossenny Plwyf/ Parish: Abergavenny Llantilio Monmouthshire Crossenny NP7 8TA Community Council Llantilio DM/2021/00467 The demolition of 3 Ash Grove Approve 22.03.2021 Delegated Officer Crossenny existing single story Brynderi Road extension. Groundwork's Llantilio Crossenny Plwyf/ Parish: for new extension Abergavenny Llantilio footings, with private NP7 8TE Crossenny drainage included. The Community construction of a new Council two story extension, compliant to permitted development which includes doors and windows on the rear of property. -

Project Newsletter Vol.1 No.2 Nov 1983

The ROATH LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY was formed in November 1978. Its objects include collecting, interpreting and disseminating information about the old ecclesiastical parish of Roath, which covered an area which includes not only the present district of Roath but also Splott, Pengam, Tremorfa, Adamsdown, Pen-y-lan and parts of Cathays and Cyncoed. Meetings are held every Thursday during school term at 7.15 p.m. at Albany Road Junior School, Albany Road, Cardiff. The Society works in association with the Exra-mural Department of the University College, Cardiff who organise an annual series of lectures (Fee:£8.50) during the Autumn term at Albany Road School also on Thursday evenings. Students enrolling for the course of ten Extra-mural lectures may join the Society at a reduced fee of £3. for the period 1 January to 30 September 1984. The ordinary membership subscription for the whole year (1 October to 30 September 1984) is £5. Members receive free "Project Newsletters" containing results of research as well as snippets of interest to all who wish to find out more about the history of Roath. They have an opportunity to assist in group projects under expert guidance and to join in guided tours to Places of local historic interest. Chairman: Alec Keir, 6 Melrose Avenue, Pen-y-lan,Cardiff. Tel.482265 Secretary: Jeff Childs, 30 Birithdir Street,Cathays, Cardiff. Tel.40038 Treasurer: Gerry Penfold, 28 Blenheim Close, Highlight Park, Barry, S Glam Tel: (091) 742340 ABBREVIATIONS The following abbreviations may be used in the Project Newsletters Admon. Letters of Administration Arch.Camb. -

Handbook to Cardiff and the Neighborhood (With Map)

HANDBOOK British Asscciation CARUTFF1920. BRITISH ASSOCIATION CARDIFF MEETING, 1920. Handbook to Cardiff AND THE NEIGHBOURHOOD (WITH MAP). Prepared by various Authors for the Publication Sub-Committee, and edited by HOWARD M. HALLETT. F.E.S. CARDIFF. MCMXX. PREFACE. This Handbook has been prepared under the direction of the Publications Sub-Committee, and edited by Mr. H. M. Hallett. They desire me as Chairman to place on record their thanks to the various authors who have supplied articles. It is a matter for regret that the state of Mr. Ward's health did not permit him to prepare an account of the Roman antiquities. D. R. Paterson. Cardiff, August, 1920. — ....,.., CONTENTS. PAGE Preface Prehistoric Remains in Cardiff and Neiglibourhood (John Ward) . 1 The Lordship of Glamorgan (J. S. Corbett) . 22 Local Place-Names (H. J. Randall) . 54 Cardiff and its Municipal Government (J. L. Wheatley) . 63 The Public Buildings of Cardiff (W. S. Purchox and Harry Farr) . 73 Education in Cardiff (H. M. Thompson) . 86 The Cardiff Public Liljrary (Harry Farr) . 104 The History of iNIuseums in Cardiff I.—The Museum as a Municipal Institution (John Ward) . 112 II. —The Museum as a National Institution (A. H. Lee) 119 The Railways of the Cardiff District (Tho^. H. Walker) 125 The Docks of the District (W. J. Holloway) . 143 Shipping (R. O. Sanderson) . 155 Mining Features of the South Wales Coalfield (Hugh Brajiwell) . 160 Coal Trade of South Wales (Finlay A. Gibson) . 169 Iron and Steel (David E. Roberts) . 176 Ship Repairing (T. Allan Johnson) . 182 Pateift Fuel Industry (Guy de G. -

'Daylight Upon Magic': Stained Glass and the Victorian Monarchy

‘Daylight upon magic’: Stained Glass and the Victorian Monarchy Michael Ledger-Lomas If it help, through the senses, to bring home to the heart one more true idea of the glory and the tenderness of God, to stir up one deeper feeling of love, and thankfulness for an example so noble, to mould one life to more earnest walking after such a pattern of self-devotion, or to cast one gleam of brightness and hope over sorrow, by its witness to a continuous life in Christ, in and beyond the grave, their end will have been attained.1 Thus Canon Charles Leslie Courtenay (1816–1894) ended his account of the memorial window to the Prince Consort which the chapter of St George’s Chapel, Windsor had commissioned from George Gilbert Scott and Clayton and Bell. Erected in time for the wedding of Albert’s son the Prince of Wales in 1863, the window attempted to ‘combine the two ele- ments, the purely memorial and the purely religious […] giving to the strictly memorial part, a religious, whilst fully preserving in the strictly religious part, a memorial character’. For Courtenay, a former chaplain- in-ordinary to Queen Victoria, the window asserted the significance of the ‘domestic chapel of the Sovereign’s residence’ in the cult of the Prince Consort, even if Albert’s body had only briefly rested there before being moved to the private mausoleum Victoria was building at Frogmore. This window not only staked a claim but preached a sermon. It proclaimed the ‘Incarnation of the Son of God’, which is the ‘source of all human holiness, the security of the continuousness of life and love in Him, the assurance of the Communion of Saints’. -

Planning Committee Chairmans Urgent 26 June 2019

CHAIRMANS URGENT ITEM THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE 26 JUNE 2019 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING MATTER WHICH THE CHAIRMAN HAS DECIDED IS URGENT BY REASON THAT THIS APPLICATION WOULD NORMALLY BE DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS BUT HAS BEEN ‘CALLED IN’ BY THE LOCAL MEMBER. THE COUNCIL HAS ENTERED INTO A PLANNING PERFORMANCE AGREEMENT TO ENSURE THE APPLICATION IS DEALT WITH PROMPTLY IN LIGHT OF THE POTENTIAL ECONOMIC BENEFITS IT PROVIDES, AND AS ALL MATTERS HAVE BEEN CONSIDERED TO ENABLE A RECOMMENDATION TO BE MADE, IT IS CONSIDERED EXPEDIENT TO REPORT THE MATTER TO THE FIRST AVAILABLE COMMITTEE TO PREVENT UNNECESSARY DELAY. 2019/00532/FUL Received on 23 May 2019 Mr Stephen Leeke J H Leeke & Sons Ltd.,, Hensol Castle, Hensol Castle Park, Hensol, Vale of Glamorgan, CF72 8JX Mr Stephen Leeke J H Leeke & Sons Ltd.,, Hensol Castle, Hensol Castle Park, Hensol, Vale of Glamorgan, CF72 8JX Hensol Castle, Hensol Castle Park, Hensol Change of use of part of the approved bar / restaurant building for the hotel, for use as a gin distillery REASON FOR COMMITTEE DETERMINATION The application is required to be determined by Planning Committee under the Council’s approved scheme of delegation because the application has been called in for determination by Councillor M. Morgan because he regards the proposal as a matter of public interest. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY P.1 This is an application for full planning permission to use part of an existing basement at Hensol Castle as a gin distillery and warehouse in association with the approved hotel and restaurant use. -

NEWSLETTER September 2016

________________________________________________________________________________________ NEWSLETTER September 2016 www.womansarchivewales.org_______________________________________________________________ Eisteddfod 2016 The WAW lecture at the Eisteddfod this year was full of the usual attendees as well as new faces from all over Wales and from Abergavenny itself. The theme was ‘The Suffagettes, the ‘Steddfod and more …’ and the lecturers were Dr Ryland Wallace and Dr Elin Jones. Ryland’s learned and witty talk was received with enthusiasm. He described how the 1912 National Eisteddfod held in Wrexham was the object of Suffragette demonstrations, especially directed at Lloyd George. The 1913 Eisteddfod, the last one held in Abergavenny, was not going to be caught out, and the Pavilion was protected with fencing and a guard dog. Then, Elin Jones presented a lively and comprehensive lecture, based on the research and book by Professor Angela John, on Magaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda, a business woman and noted Suffragette. The session was chaired by Dr Siân Rhiannon Williams. The tent was packed, and it was a lovely day. Women in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography National biographies are a way of making a nation by creating its memory and recording the lives of those people who have shaped it. Therefore, who is included in this repository and resource is very important. Women are still under-represented in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, which was launched in 1937 and for which the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies and the National Library of Wales have been responsible since January 2014. Although the DWB’s statistics look no worse than those of most other national biographies, we have to concede that even in 2016, only about 10% of authors contributing entries to the DWB were women. -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales Cymorth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Lady Charlotte Guest Manuscripts (GB 0210 GUEST) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 24, 2019 Printed: May 24, 2019 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/lady-charlotte-guest-manuscripts https://archives.library.wales/index.php/lady-charlotte-guest-manuscripts Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Lady Charlotte Guest Manuscripts Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 4 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

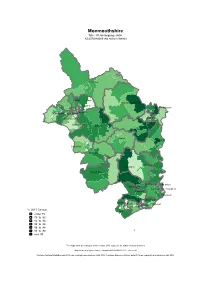

Monmouthshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Monmouthshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Crucorney Cantref Mardy Llantilio Crossenny Croesonen Lansdown Dixton with Osbaston Priory Llanelly Hill GrofieldCastle Wyesham Drybridge Llanwenarth Ultra Overmonnow Llanfoist Fawr Llanover Mitchel Troy Raglan Trellech United Goetre Fawr Llanbadoc Usk St. Arvans Devauden Llangybi Fawr St. Kingsmark St. Mary's Shirenewton Larkfield St. Christopher's Caerwent Thornwell Dewstow Caldicot Castle The Elms Rogiet West End Portskewett Green Lane %, 2011 Census Severn Mill under 79 79 to 82 82 to 84 84 to 86 86 to 88 88 to 90 over 90 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Monmouthshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Crucorney Mardy Llantilio Crossenny Cantref Lansdown Croesonen Priory Dixton with Osbaston Llanelly Hill Grofield Castle Drybridge Wyesham Llanwenarth Ultra Llanfoist Fawr Overmonnow Llanover Mitchel Troy Goetre Fawr Raglan Trellech United Llanbadoc Usk St. Arvans Devauden Llangybi Fawr St. Kingsmark St. Mary's Shirenewton Larkfield St. Christopher's Caerwent Thornwell Caldicot Castle Portskewett Rogiet Dewstow Green Lane The Elms %, 2011 Census West End Severn Mill under 1 1 to 2 2 to 2 2 to 3 3 to 4 4 to 5 over 5 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 -

Plu Hydref 2011 Fersiwn

PAPUR BRO LLANGADFAN, LLANERFYL, FOEL, LLANFAIR CAEREINION, ADFA, CEFNCOCH, LLWYDIARTH, LLANGYNYW, CWMGOLAU, DOLANOG, RHIWHIRIAETH, PONTROBERT, MEIFOD, TREFALDWYN A’R TRALLWM. 426 Hydref 2017 60c BRENIN Y BOWLIO LLYWYDDION LLAWEN Ar brynhawn Sul gwlyb yn ddiweddar chwaraewyd twrnamaint bowlio yn Llanfair Caereinion. Er gwaetha’r tywydd roedd y cystadleuwyr yn benderfynol o orffen y gystadleuaeth gan fod y ‘Rose Bowl’ yn wobr mor hynod o dlws i’w hennill. Yn y gêm derfynol roedd Gwyndaf James yn chwarae yn erbyn y g@r profiadol Llun Michael Williams Richard Edwards. Gwyndaf oedd y pencampwr hapus a fo gafodd ei ddwylo ar y ‘Rose Bowl’. Rwan mae Enillwyr y stondin fasnach orau ar faes y Sioe eleni oedd stondin ar y cyd Philip angen dod o hyd i le parchus i arddangos y wobr Edwards, For Farmers a H.V. Bowen. Gwelir Huw, Guto a Rhidian Glyn o For Farm- arbennig hon! ers; Mark Bowen a Philip yn derbyn eu gwobr gan Enid ac Arwel Jones. DWY NAIN FALCH Mae dwy nain falch iawn yn Nyffryn Banw yn dilyn yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol yn Sir Fôn ym mis Awst. Uchod gwelir Dilys, Nyth y Dryw, Llangadfan gyda’i h@yr Steffan Prys Roberts, Llanuwchllyn a enillodd wobr y Rhuban Glas. Mae Steff yn gweithio i’r Urdd yng Nglanllyn ac yn aelod o Gwmni Theatr Maldwyn, tri chôr a sawl parti canu! Nain arall sy’n byrlymu â balchder yw Marion Owen, Rhiwfelen, Foel sy’n ymfalchïo yn llwyddiant ei hwyres Marged Elin Owen a enillodd Ysgoloriaeth yr Artist Ifanc. Mae Marged bellach wedi cael swydd gyda chwmni castio gwydr y tu allan i Blackpool. -

Framing Welsh Identity Moya Jones

Framing Welsh identity Moya Jones To cite this version: Moya Jones. Framing Welsh identity. Textes & Contextes, Université de Bourgogne, Centre Interlangues TIL, 2008, Identités nationales, identités régionales, https://preo.u- bourgogne.fr/textesetcontextes/index.php?id=109. halshs-00317835v2 HAL Id: halshs-00317835 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00317835v2 Submitted on 8 Sep 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Article tiré de : Textes et Contextes. [Ressource électronique] / Centre de Recherche Interlangues « texte image langage ». N°1, « identités nationales, identités régionales ». (2008). ISSN : 1961-991X. Disponible sur internet : http://revuesshs.u-bourgogne.fr/textes&contextes/ Framing Welsh identity Moya Jones, UMR 5222 CNRS "Europe, Européanité, Européanisation ", UFR des Pays anglophones, Université Michel de Montaigne - Bordeaux 3, Domaine universitaire, 33607 Pessac Cedex, France, http://eee.aquitaine.cnrs.fr/accueil.htm, moya.jones [at] u-bordeaux3.fr Abstract Welsh Studies as a cross-disciplinary field is growing both in Wales and beyond. Historians, sociologists, political scientists and others are increasingly collaborating in their study of the evolution of Welsh identity. This concept which was for so long monopolised and marked by a strong reference to the Welsh language and the importance of having an ethnic Welsh identity is now giving way to a more inclusive notion of what it means to be Welsh.