Newsletter 46 January 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hythe Ward Hythe Ward

Cheriton Shepway Ward Profile May 2015 Hythe Ward Hythe Ward -2- Hythe Ward Foreword ..........................................................................................................5 Brief Introduction to area .............................................................................6 Map of area ......................................................................................................7 Demographic ...................................................................................................8 Local economy ...............................................................................................11 Transport links ..............................................................................................16 Education and skills .....................................................................................17 Health & Wellbeing .....................................................................................22 Housing .........................................................................................................33 Neighbourhood/community ..................................................................... 36 Planning & Development ............................................................................41 Physical Assets ............................................................................................ 42 Arts and culture ..........................................................................................48 Crime .......................................................................................................... -

First Carey Conference in Africa

Editorial Bible Conferences News. Reporting is restricted because the political sihiation in Burma is precarious. There is a vast need in the developing Pastors are subject to persecution. The world, Asia, Latin America and Africa for needs in the sub-continent of India are sound theological training. In these areas almost identi cal to those of Africa. It is Bible-beli eving Christians continue to becoming more difficu lt for Chri stian multiply and there are innumerable workers to obtain visas for India and this in digenous pastors who are wi lling to must surely be a matter of prayer. travel long distances and undergo hardship to be able to improve and refine Th e Life and Legacies of Doctor Martyn understanding of the Bible. They hunger Lloyd-Jones to develop their ski ll s in expository preaching and to grow in their grasp of Doctor David Martyn Lloyd-fones died Biblical, Systematic and Historical on St David's Day (l" March) 198 1. He Theology. Areas of acute need are an was born at the end of the reign of Queen understanding of the attributes of God, a Victoria and lived through 29 years of the grip of God's way of salvation in li eu of reign of Queen Eli zabeth II. His life an over-simplified decisionism, the spanned th e two great World Wars. He doch·ine of progressive sanctification, and ministered tlu·ough the years of the great helps and inspiration for godly, economic depression of the 1930s. He disciplined living in the home and at worked in the heart of London when that work. -

Westminster Chapel - What Happened?

Visit our website www.reformation-today.org Editorial comment Foll owin g the expositi on by Spencer C unnah on the role of the pastor whi ch appeared in the last issue (RT 192), Robert Stri vens shows that theology is the driv ing force in the pastor's li fe and how important it is that every pastor be a theologian. But it is not all stud y. The pastor needs to relate to his people and be w ith them by way of hospita lity or by visitation. That subject is addressed in the artic le on visitation . The degree to which writing on visitation has been neglected is illustrated by th e fact that there is onl y one entry fo r it the new 2003 The FINDER (Banner ofTruth 1955-2002, RT 1970- 2002, Westminster Conference 1955-2002). The above emphasis on the pastor as theologian should not detract from the fact that every Christian is a theologian, not in the sense of being a specialist but certainly in the sense of knowing God and be ing proficient in C hri stian truth . Contributors to this issue Robert Strivens practised as a soli citor in London and Brussels for 12 years before training fo r the pastoral ministry at London Theological Seminary ( 1997-99). In 1999, he was call ed to the pastorate of Banbury Evangeli cal Free C hurch, founded 18 years ago. He li ves in Banbury with hi s w ife Sarah and three children, David, Thomas and Danie l. Roger We il has devoted hi s life to visiting and working with pastors in Eastern Europe. -

West Sussex County Council

PRINCIPAL LOCAL BUS SERVICES BUS OPERATORS RAIL SERVICES GettingGetting AroundAround A.M.K. Coaches, Mill Lane, Passfield, Liphook, Hants, GU30 7RP AK Eurostar Showing route number, operator and basic frequency. For explanation of operator code see list of operators. Telephone: Liphook (01428) 751675 WestWest SussexSussex Website: www.AMKXL.com Telephone: 08432 186186 Some school and other special services are not shown. A Sunday service is normally provided on Public Holidays. Website: www.eurostar.co.uk AR ARRIVA Serving Surrey & West Sussex, Friary Bus Station, Guildford, by Public Transport Surrey, GU1 4YP First Capital Connect by Public Transport APPROXIMATE APPROXIMATE Telephone: 0844 800 4411 Telephone: 0845 026 4700 SERVICE FREQUENCY INTERVALS SERVICE FREQUENCY INTERVALS Website: www.arrivabus.co.uk ROUTE DESCRIPTION OPERATOR ROUTE DESCRIPTION OPERATOR Website: www.firstcapitalconnect.co.uk NO. NO. AS Amberley and Slindon Village Bus Committee, Pump Cottage, MON - SAT EVENING SUNDAY MON - SAT EVENING SUNDAY Church Hill, Slindon, Arundel, West Sussex BN18 0RB First Great Western Telephone: Slindon (01243) 814446 Telephone: 08457 000125 Star 1 Elmer-Bognor Regis-South Bersted SD 20 mins - - 100 Crawley-Horley-Redhill MB 20 mins hourly hourly Website: www.firstgreatwestern.co.uk Map & Guide BH Brighton and Hove, Conway Street, Hove, East Sussex BN3 3LT 1 Worthing-Findon SD 30 mins - - 100 Horsham-Billingshurst-Pulborough-Henfield-Burgess Hill CP hourly - - Telephone: Brighton (01273) 886200 Gatwick Express Website: www.buses.co.uk -

Sundials, Solar Rays, and St Paul's Cathedral

Extract from: Babylonian London, Nimrod, and the Secret War Against God by Jeremy James, 2014. Sundials, Solar Rays, and St Paul's Cathedral Since London is a Solar City – with St Paul's Cathedral representing the "sun" – we should expect to find evidence of solar rays , the symbolic use of Asherim to depict the radiant, life-sustaining power of the sun. Such a feature would seem to be required by the Babylonian worldview, where Asherim are conceived as conduits of hidden power, visible portals through which the gods radiate their "beneficent" energies into the universe. The spires and towers of 46 churches are aligned with the center of the dome of St Paul's Cathedral, creating 23 "solar rays". I was already familiar with this idea from my research into the monuments of Dublin, where church steeples and other Asherim are aligned in radial fashion around the "sun," the huge modern obelisk known as the Millennium Spire. As it happens, a total of 23 "solar rays" pass through the center of the dome of St Paul's Cathedral, based on the alignment of churches alone . Thus, in the diagram above, two churches sit on each line. If other types of Asherim are included – such as obelisks, monoliths, columns and cemetery chapels – the number is substantially greater. [The 46 churches in question are listed in the table below .] 1 www.zephaniah.eu The churches comprising the 23 "rays" emanating from St Paul's Cathedral 1 St Stephen's, Westbourne Park St Paul's Cathedral St Michael's Cornhill 2 All Souls Langham Place St Paul's Cathedral St Paul's Shadwell -

Congregationalism in Edwardian Hampshire 1901-1914

FAITH AND GOOD WORKS: CONGREGATIONALISM IN EDWARDIAN HAMPSHIRE 1901-1914 by ROGER MARTIN OTTEWILL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Congregationalists were a major presence in the ecclesiastical landscape of Edwardian Hampshire. With a number of churches in the major urban centres of Southampton, Portsmouth and Bournemouth, and places of worship in most market towns and many villages they were much in evidence and their activities received extensive coverage in the local press. Their leaders, both clerical and lay, were often prominent figures in the local community as they sought to give expression to their Evangelical convictions tempered with a strong social conscience. From what they had to say about Congregational leadership, identity, doctrine and relations with the wider world and indeed their relative silence on the issue of gender relations, something of the essence of Edwardian Congregationalism emerges. In their discourses various tensions were to the fore, including those between faith and good works; the spiritual and secular impulses at the heart of the institutional principle; and the conflicting priorities of churches and society at large. -

The Parish of Durris

THE PARISH OF DURRIS Some Historical Sketches ROBIN JACKSON Acknowledgments I am particularly grateful for the generous financial support given by The Cowdray Trust and The Laitt Legacy that enabled the printing of this book. Writing this history would not have been possible without the very considerable assistance, advice and encouragement offered by a wide range of individuals and to them I extend my sincere gratitude. If there are any omissions, I apologise. Sir William Arbuthnott, WikiTree Diane Baptie, Scots Archives Search, Edinburgh Rev. Jean Boyd, Minister, Drumoak-Durris Church Gordon Casely, Herald Strategy Ltd Neville Cullingford, ROC Archives Margaret Davidson, Grampian Ancestry Norman Davidson, Huntly, Aberdeenshire Dr David Davies, Chair of Research Committee, Society for Nautical Research Stephen Deed, Librarian, Archive and Museum Service, Royal College of Physicians Stuart Donald, Archivist, Diocesan Archives, Aberdeen Dr Lydia Ferguson, Principal Librarian, Trinity College, Dublin Robert Harper, Durris, Kincardineshire Nancy Jackson, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Katy Kavanagh, Archivist, Aberdeen City Council Lorna Kinnaird, Dunedin Links Genealogy, Edinburgh Moira Kite, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire David Langrish, National Archives, London Dr David Mitchell, Visiting Research Fellow, Institute of Historical Research, University of London Margaret Moles, Archivist, Wiltshire Council Marion McNeil, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Effie Moneypenny, Stuart Yacht Research Group Gay Murton, Aberdeen and North East Scotland Family History Society, -

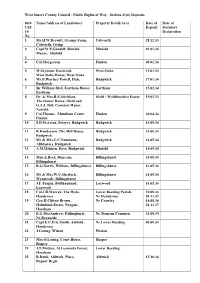

Section 31(6) Deposits 06/0 1/20 10 No. Name/Address of Landowner

West Sussex County Council - Public Rights of Way - Section 31(6) Deposits 06/0 Name/Address of Landowner Property Detail/Area Date of Date of 1/20 Deposit Statutory 10 Declaration No. 1 Mr.H.W.Drewitt, Grange Farm, Colworth 28.12.33 Colworth, Oving 2 Capt.W.P.Gandell, Slinfold Slinfold 01.01.34 Manor, Slinfold 3 4 Col.Margesson Findon 05.01.34 5 W.Seymour Eastwood, West Stoke 12.01.34 West Stoke House, West Stoke 6 Mr.B.Worlsey Powell, Hale, Rudgwick 17.01.34 Rudgwick 7 Sir William Bird, Eartham House, Eartham 15.02.34 Eartham 8 Dr. & Mrs.R.S.Aitchison, Ifield - Woldhurstlea Estate 19.02.34 The Dower House, Ifield and G.A.J. Bell, Cawston Manor, Norfolk. 9 Col.Thynne, Muntham Court, Findon 30.04.34 Findon 10 S.D.Secretan, Swayes, Rudgwick Rudgwick 14.05.34 11 R.Henderson, The Mill House, Rudgwick 14.05.34 Rudgwick 12 Mr & Mrs.C.C.Naumann, Rudgwick 14.05.34 Aliblasters, Rudgwick 13 A.M.Holman, Hyes, Rudgwick Slinfold 14.05.34 14 Miss E.Beck, Duncans, Billingshurst 14.05.34 Billingshurst 15 R.G.Norris, Wildens, Billingshurst Billingshurst 14.05.34 16 Mr & Mrs.W.U.Sherlock, Billingshurst 14.05.34 Wynstrode, Billingshurst 17 J.F.Turpin, Beldhamland, Loxwood 14.05.34 Loxwood 18 Col.J.R.Warren, The Hyde, Lower Beeding Parish, 10.08.34 Handcross Nr.Handcross 24.11.37 19 Gen.H.Clifton-Brown, Nr.Crawley 16.08.34 Holmbush Estate, Faygate, 24.11.37 Horsham 20 E.G.MacAndrew, Pallinghurst, Nr.Tismans Common 31.08.34 Nr.Baynards 21 Capt.E.C.Eric Smith, Ashfold , Nr.Lower Beeding 05.09.34 Handcross 22 J.Goring, Wiston Wiston 23 Mrs.O.Loring, Court House, Rusper Rusper 24 J.T.McGaw, St.Leonards Forest, Lower Beeding Horsham 25 R.Rank, Aldwick Place, Aldwick 15.10.34 Bognor Regis No. -

PREACHING PLACES and MEETING HOUSES a Provisional Gazetteer of Nineteenth-Century Protestant Nonconformity in Southampton by Veronica Green

PREACHING PLACES AND MEETING HOUSES A Provisional Gazetteer of Nineteenth-Century Protestant Nonconformity in Southampton By Veronica Green Nineteenth-century nonconformists were prone to rebellion and revival, to schism and secession. New congregations arose by division from an existing church, by the missionary efforts of travelling preachers, by the inspiration of charismatic evangelists. They met in rooms over pubs and workshops, in scaffold lofts and converted laundries. They rented the Victoria Rooms, of the Philharmonic Hall, or Mr Monk’s Schoolroom, until they could build for themselves, or come into an inheritance from another denomination moving on to better things, or failing to keep up the payments on an ambitious building. Some of the back-street chapels and the smaller groups played “musical chapels” well into this century. This is a chapel gazetteer, in that it lists nonconformist places of worship. It is not only a list of chapels, that is, buildings used exclusively for worship, but also of known meeting rooms and private houses used for worship. It attempts to trace the history of worshippers as well as the buildings they worshipped in, and for the moment it concentrates on the old borough before the boundary extensions in 1895. It excludes the French Protestant congregation at St Julian’s, which had conformed in the eighteenth century, and Roman Catholics, who were listed as “nonconformists” in nineteenth-century directories, but would not now be so described. Basic sources, other than those mentioned in the text, are: Directories 1803-1899 Appendix A: Buildings used as Methodist places of worship, in The story of St Andrew’s Methodist Church, Sholing, by James W M Brown, Sholing Press, 1995 Willis, Arthur J: A Hampshire Miscellany, Vol. -

Chichester District Council Schedule of Planning Appeals, Court And

Chichester District Council Planning Committee Wednesday 06 May 2020 Report of the Director Of Planning and Environment Services Schedule of Planning Appeals, Court and Policy Matters Between 19-Feb 2020 and 15-Apr-2020 This report updates Planning Committee members on current appeals and other matters. It would be of assistance if specific questions on individual cases could be directed to officers in advance of the meeting. Note for public viewing via Chichester District Council web siteTo read each file in detail, including the full appeal decision when it is issued, click on the reference number (NB certain enforcement cases are not open for public inspection, but you will be able to see the key papers via the automatic link to the Planning Inspectorate). * - Committee level decision. 1. NEW APPEALS (Lodged) Reference/Procedure Proposal 19/01240/FUL Land South West Of Guidford Road Loxwood West Loxwood Parish Sussex - Demolition of existing dwelling and the erection of 50 dwellings to include 35 private units and 15 affordable units, creation of proposed vehicular access, internal roads Case Officer: Jeremy Bushell and footpaths, car parking, sustainable drainage system, open space with associated landscaping and amenity space. Public Inquiry 19/00141/CONHH Oakham Farmhouse Church Lane Oving Chichester West Oving Parish Sussex PO20 2BT - Appeal against a fence in excess of 1 metre in height erected adjacent to the highway, subject to Enforcement Notice O/30. Case Officer: Emma Kierans Written Representation Reference/Procedure Proposal -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Re-Imagining Methodist Property Living Buildings: Adaptation and Reuse

Re-imagining Methodist Property Living Buildings: Adaptation and Reuse Reimagining Methodist Property i Who we are Founded 60 years ago by Sir Donald Insall, we are an employee-owned team of 120 with offices in London, Birmingham, Chester and Cambridge and studios in Bath, Oxford, Manchester and Conwy. As well as architects, the team includes historians, former Conservation Officers and Historic England Inspectors. Our motto is ‘Living Buildings.’ Most of our work is in the UK but we also advise abroad with jobs in Trinidad and Tobago, Abu Dubai and India. Reimagining Methodist Property Methodist Property Holdings: Heritage Assets “In 2006 there were about 5,312 [Methodist] chapels in England of which 869 (16 per cent) are listed.’”– Historic England, Places of Worship Listing Selection Guide (2017). Listed buildings also include: Central Halls (unique to Methodism), Sunday schools, halls, manses, stables and open sites. Reimagining Methodist Property Types of Heritage Assets • Grade I buildings are of exceptional interest, only 2.5% of listed buildings are Grade I. • Grade II* buildings are particularly important buildings of more than special interest; 5.8% of listed buildings are Grade II*. • Grade II buildings are of special interest; 91.7% of all listed buildings are in this class and it is the most likely grade of listing for a home owner. Often buildings that have had some alterations or important historically rather than architecturally. They are still protected externally and internally. Reimagining Methodist Property Grade I Capel Peniel in Tremadog, Gwynedd. Built 1810-11 and credited with influencing the architecture of later Welsh chapels.