The Parish of Durris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

YOUR EVENT at the LONACH HALL Thank You for Considering the Lonach Hall for Your Event

YOUR EVENT AT THE LONACH HALL Thank you for considering the Lonach Hall for your event. It is a wonderful venue in a scenic setting, easily reached by many companies which supply services for meetings, weddings and other functions. FOOD CATERING Please note that if your caterer has not worked at the Hall before, we suggest that before you confirm your booking with them, you visit the Hall with them. Those which are closest, or used to catering at the Hall, are shown first. Colquhonnie Hotel, Strathdon AB36 8UN Tel: (019756) 51210 Web: www.colquhonnie.co.uk (next door to the Hall). Contact Paul or David. The Glenkindie Arms Hotel, Glenkindie, Tel: (019756) 41288 E-mail: [email protected] Aberdeenshire AB33 8SX Contact Eddie / 07854 920172 (also have in-house brewery) / 07971 436354 Spar Shop, Bellabeg, Strathdon, AB36 8UL Tel: (019756) 51211 Contact Paul Toohey (Sale/return on selected food & drink for functions) Harry Fraser Catering Ltd, Tel: (01467) 622008 E-mail: [email protected] Inverurie Food Park, Blackhall Industrial Estate, Inverurie Contact Harry or Gwen. Highland Cuisine, Thainstone Tel: (01467) 623867 Web: www.goanm.co.uk/highlandcuisine Agricultural Centre, Thainstone, Inverurie Buchanan Food, Stables Cottage, Tel: (013398) 87073 E-mail: [email protected] Birsemhor Lodge, Aboyne AB34 5ES / 07743 308039 Contact Val or Callum Deeside Cuisine Ltd, Tel: (01330) 820813 E-mail: [email protected] 4 Cherry Tree Road, Hill of Banchory West, Banchory AB31 5NW Hudson’s Catering, Tel: (01224) 791100 Web: www.hudsonscatering.co.uk Units 14/15 Blackburn Industrial Estate, Kinellar, Aberdeen AB21 0RX Contact Gillian. -

Ideas to Inspire

2016 - Year of Innovation, Architecture and Design Speyside Whisky Festival Dunrobin Castle Dunvegan Castle interior Harris Tweed Bag Ideas to inspire Aberdeenshire, Moray, Speyside, the Highlands and the Outer Hebrides In 2016 Scotland will celebrate and showcase its historic and contemporary contributions to Innovation, Architecture and Events: Design. We’ll be celebrating the beauty and importance of our Spirit of Speyside Whisky Festival - Early May – Speyside whiskies are built heritage, modern landmarks and innovative design, as well famous throughout the world. Historic malt whisky distilleries are found all as the people behind some of Scotland’s greatest creations. along the length of the River Spey using the clear water to produce some of our best loved malts. Uncover the development of whisky making over the Aberdeenshire is a place on contrasts. In the city of Aberdeen, years in this stunning setting. www.spiritofspeyside.com ancient fishing traditions and more recent links with the North Festival of Architecture - throughout the year – Since 2016 is our Year of Sea oil and gas industries means that it has always been at the Innovation, Architecture and Design, we’ll celebrate our rich architectural past and present with a Festival of Architecture taking place across the vanguard of developments in both industries. Aberdeenshire, nation. Morayshire and Strathspey and where you can also find the Doors Open Days - September – Every weekend throughout September, greatest density of castles in Scotland. buildings not normally open to the public throw open their doors to allow visitors and exclusive peak behind the scenes at museums, offices, factories, The rugged and unspoiled landscapes of the Highlands of and many more surprising places, all free of charge. -

Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette 1837-1855

Moray & Nairn Family History Society Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette 18371837----1818181855555555 Compiled by Douglas G J Stewart No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Moray & Nairn Family History Society . Copyright © 2015 Moray & Nairn Family History Society First published 2015 Published by Moray & Nairn Family History Society 2 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements .................................................................................. 4 Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette: 1837 ......................................................................................................................... 7 1838 ......................................................................................................................... 7 1839 ....................................................................................................................... 10 1840 ....................................................................................................................... 11 1841 ....................................................................................................................... 14 1842 ....................................................................................................................... 16 1843 ...................................................................................................................... -

Family of George Brebner and Janet Jack, Durris, KCD February 6Th, 2015

Family of George Brebner and Janet Jack, Durris, KCD February 6th, 2015 Generation One 1. George Brebner #1090, b. c 1775 in Durris?, KCD, SCT. It's likely that George is related to James Brebner and Isobel Gillespie... He married Janet Jack #1091, in (no record in OPRI), b. c 1775 in Durris?, KCD, SCT, d. 04 August 1817 in Durris? KCD, SCT.1 Children: 2. i. George Brebner #1094 b. January 1798. 3. ii. Christian Brebner #1093 b. July 1800. 4. iii. John Brebner #2474 b. August 1802. 5. iv. James Brebner #1095 b. 03 May 1806. 6. v. Alexander Brebner #14562 b. 14 April 1809. 7. vi. Jean Brebner #1096 b. 04 April 1811. Generation Two 2. George Brebner #1094, b. January 1798 in Durris, KCD, SCT, baptized 28 January 1798 in Uppertown of Blearydrine, Durris, KCD,2 d. 28 April 1890 in Broomhead, Durris, KCD, SCT,3 buried in Durris Kirkyard, KCD, SCT,4 occupation Miller/Farmer. 1841-51: Lived at Mill of Blearydrine, Durris. 1851: Farmed 55 acres. 1881: Lived with wife Ann at son-in-law William REITH's farm. He married Ann Ewan #1098, 05 July 1825 in Durris, KCD, SCT, b. 1799 in Kinneff, KCD, SCT,5 (daughter of James Ewan #10458 and Ann Watt #10459), baptized 29 January 1800 in Kinneff & Catterline, KCD, SCT,6 d. 07 July 1881 in Broomhead, Durris, KCD, SCT,7 buried in Durris Kirkyard, KCD, SCT.4 Ann: 1881: Lived with son-in-law William REITH. Children: 8. i. William Brebner #1822 b. c 1825. 9. ii. -

Family and Estate Papers in Special Collections Andrew Macgregor, May 2018 QG HCOL018 [

Library guide Family and estate papers in Special Collections Andrew MacGregor, May 2018 QG HCOL018 [www.abdn.ac.uk/special-collections/documents/guides/qghcol018.pdf] The Wolfson Reading Room Burnett of Leys (Crathes Castle papers): 14th century – 20th century (MS 3361). Special Collections Centre The Sir Duncan Rice Library Chalmers family, Aberdeen: 1845 – 1966 (MS 2884). University of Aberdeen Bedford Road Davidson of Kebbaty, Midmar, Aberdeenshire: Aberdeen 1711 – 1878 (MS 4018). AB24 3AA Dingwall Fordyce of Brucklay family: th th Tel. (01224)272598 16 century – 19 century (MS 999). E–mail: [email protected] Dunecht Estate Office (Viscounts of Cowdray): Website: www.abdn.ac.uk/special-collections 18th century to 20th century (MS 3040). Dalrymple of Tullos, Nigg, Aberdeen: Introduction 1813 – 1937 (MS 3700). Many notable families have deposited their papers Douglas of Glenbervie and Nicolson of Glenbervie: with the University and as a result it has acquired 15th century – 20th century (MS 3021). an unrivalled collection of material relating to the history and culture of the north-east of Scotland. Duff of Braco and Wharton-Duff of Orton: 17th century – 19th century: (MS 2727). These archives are fantastically rich for the study of th estate management, local and regional politics, law Duff, Earls of Fife (Duff House): 13 century – th enforcement, art and architecture, foreign trade, 20 century (MS 3175). military adventure and colonial power. Duff of Meldrum: 15th century – 19th century (MS Some collections are particularly rich for family 2778). For more material relating to the Duffs see the main Earls of Fife catalogue, MS 3175, above. -

THE ROYAL CASTLE of KINDKOCHIT in MAR. 75 III. the ROYAL CASTLE OP KINDROCHIT in MAR. SIMPSON, M.A., F.S.A.Scot. by W. DOUGLAS T

THE ROYAL CASTLE OF KINDKOCHIT IN MAR. 75 III. E ROYATH L CASTL P KINDROCHIO E MARN I T . BY W. DOUGLAS SIMPSON, M.A., F.S.A.ScOT. The scanty remains of the great Aberdeenshire Castle of Kindrochit occup ya ver y strong positio e righth n te Clun no ban th f yo k Water, a short distance from its confluence with the Dee, and immediately above the bridge which connects the two portions (Auchendryne and Castleton e villagth f f Braemarwalle o o )e th placo n se emorar n I . e than 10 feet high, and for the greater part they are reduced to mere foundations. These fragments are much overgrown with grass and moss, and the whole sits i obscuree y larcd b d an h rowan trees, scrubby undergrowtd an h luxuriant nettles, amidst whic harde hth , metamorphic bedrock here and there n roundedi crop t ou s , ice-worn bosses. e Aeas th roat n side,o d d variouan ' s erections connected with the adjoining farm, encroach upon the precincts. Also a considerable amount of refuse has been dumped upo sitee nthath o s , t what remains of the castle is now "a desola- tion of rubbish and weeds."1 But by a careful examination of the existing masonry, and of the green mounds with protruding stones which mark buried courses of wall, it is possible to recover KINDROCHIT CASTLE. GROUND PLAN a fairly accurate ground plan (fig, 1) . althoug a hcompletel y satisfactory sur- vey would entail extensive excavation. Fig . Kindrochi1 . -

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

6 Arbuthnott Street Gourdon, DD10 0LA

6 Arbuthnott Street Gourdon, DD10 0LA Offers Over £180,000 6 Arbuthnott Street, Gourdon, DD10 0LA LOCATION Gourdon is a small fishing village on the East coast situated approximately 25 miles south of Aberdeen and 12 miles north of Montrose. The village has a picturesque working harbour, local shop with post office and a local pub. Primary schooling is catered for in the village with secondary education available at nearby Mackie Academy in Stonehaven. Additional shops and health centre can be found in Inverbervie which is approximately one mile away. DESCRIPTION This semi-detached villa enjoys a delightful location within the heart of Gourdon and enjoys sea views over the surrounding rooftops towards the North Sea. Full of character and charm this traditional property benefits from oil central heating and double glazing, is well presented and enjoys spacious accommodation over three floors. Entry is into a hallway with access to a utility/cloaks cupboard and into a rear facing lounge, rear hallway with storage cupboard and also gives access into the rear garden. Also on the ground floor is an impressive modern dining kitchen with front and rear facing windows. The kitchen is fitted with wall and base units, a five ring ceramic hob and double oven/grill with cooker hood. A central island provides additional units with seating area, sink unit and integrated dishwasher and a storage cupboard provides plumbing for an automatic washing machine. A wooden stairway leads to the first floor where a rear facing window provides views over the garden towards the sea beyond. Here there is a spacious master bedroom with adjoining en-suite shower room, 4th Bedroom/Study and the family bathroom with three piece suite and over the bath shower. -

Final Deeside Railway Inside

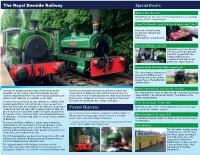

The Royal Deeside Railway Special Events Mothers Day - March 26 Bring Mum and the rest of the family along for our opening service of 2017. Steam hauled Cream Tea Specials - April 15-16, May 28, July 16, Aug 13, Sep 17 Enjoy one of our famous Cream Teas onboard our Buet Car. Trains will be steam hauled. Victorian Weekend - June 3-4 Experience our recreation of the 1860s when the Deeside Line first opened with the railway sta in period costume Cream Teas in the Buet Car. Steam hauled. Deeside Steam & Vintage Rally - August 19-20 This ever-popular event takes place in the Milton Events Fieldadjacent to the station. Cream Teas in the Buet Car. Steam hauled. Return of Bon-Accord - September 30 - October 1 The Deeside Railway operates train services from April to The line was regularly patronised by the Royal Family and December on the original route of the Deeside Line. All other visitors to Balmoral Castle until it closed in 1966 as a We celebrate the return of “Bon-Accord”, our Victorian steam journeys depart from Milton of Crathes station and take 20-25 result of the notorious Beeching Report. Thirty years later the engine built for Aberdeen Gas Works, from duties in the minutes. Refreshments are available on the train. Royal Deeside Railway Preservation Society was formed and South. Steam hauled. the work of restoring the line commeced in 2003. Steam services are hauled by our resident loco 'Salmon', built End of Season Gala - October 14-15 by Andrew Barclay in 1942. Later in the season, we welcome back sister loco 'Bon-Accord' built for the Aberdeen Corporation Private Charters Non-stop steam services throughout the weekend to mark Gasworks in 1897 and owned by Grampian Transport Museum. -

Black's Morayshire Directory, Including the Upper District of Banffshire

tfaU. 2*2. i m HE MOR CTORY. * i e^ % / X BLACKS MORAYSHIRE DIRECTORY, INCLUDING THE UPPER DISTRICTOF BANFFSHIRE. 1863^ ELGIN : PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES BLACK, ELGIN COURANT OFFICE. SOLD BY THE AGENTS FOR THE COURANT; AND BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : ELGIN PRINTED AT THE COURANT OFFICE, PREFACE, Thu ''Morayshire Directory" is issued in the hope that it will be found satisfactorily comprehensive and reliably accurate, The greatest possible care has been taken in verifying every particular contained in it ; but, where names and details are so numerous, absolute accuracy is almost impossible. A few changes have taken place since the first sheets were printed, but, so far as is known, they are unimportant, It is believed the Directory now issued may be fully depended upon as a Book of Reference, and a Guide for the County of Moray and the Upper District of Banffshire, Giving names and information for each town arid parish so fully, which has never before been attempted in a Directory for any County in the JTorth of Scotland, has enlarged the present work to a size far beyond anticipation, and has involved much expense, labour, and loss of time. It is hoped, however, that the completeness and accuracy of the Book, on which its value depends, will explain and atone for a little delay in its appearance. It has become so large that it could not be sold at the figure first mentioned without loss of money to a large extent, The price has therefore been fixed at Two and Sixpence, in order, if possible, to cover outlays, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/blacksmorayshire1863dire INDEX. -

Tipperty Farm Auchenblae, Laurencekirk

TIPPERTY FARM AUCHENBLAE, LAURENCEKIRK TIPPERTY FARM, AUCHENBLAE, LAURENCEKIRK, AB30 1UJ An exceptionally well equipped farm situated in a productive farming area. Auchenblae 2 miles ■ Laurencekirk 8 miles ■ Aberdeen 25 miles For sale as a whole or in 3 lots ■ Lot 1: Tipperty Farm comprising 2 bedroom farmhouse, an exceptional range of farm buildings, 328.29 hectares (811.20 acres) of land and Corsebauld Farmhouse and buildings Lot 1 ■ Lot 2: Land at Glenfarquhar, extending to 48.51 hectares (119.87 acres) ■ Lot 3: Land at Goosecruives, extending to 60.68 hectares (149.96 acres) Aberdeen 01224 860710 Lot 1 [email protected] LOCATION Tipperty Farm is situated 2 miles north of Auchenblae, 8 miles north of Laurencekirk and 25 miles south of Aberdeen, in the former county of Kincardineshire. VIEWING Strictly by appointing with the sole selling agents –Galbraith, 337 North Deeside Road, Cults, Aberdeen, AB15 9SN. Tel: 01224 860710. Fax: 01224 869023. Email: [email protected] DIRECTIONS Travelling north on the A90, turn left at Fordoun, signposted for Auchenblae. Continue for 2 miles and proceed into the village of Auchenblae. Continue through the village and after leaving turn left where signposted Stonehaven. Continue for a further 2 miles and Tipperty can be found on the left hand side. Travelling south on the A90 turn right at Fordoun, signposted Auchenblae and thereafter follow the directions above. SITUATION Tipperty Farm is situated approximately 2 miles north of the village of Auchenblae, 8 miles north of Laurencekirk and 25 miles south of Aberdeen in the former county of Kincardineshire. The land is of undulating nature, rising from the Howe of the Mearns, being in prime farming country.