The Neoliberal Crisis.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clothes, Immigration and Youth Identities in Britain 1965-1972

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository DRESSING RACE: CLOTHES, IMMIGRATION AND YOUTH IDENTITIES IN BRITAIN 1965-1972 by SAM HUMPHRIES A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Modern and Contemporary History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis will explore the role race plays in conceptions and performances of British identity by using clothes as a source. It will use the relationship between the body and clothes to argue that cultural understandings of race are part of the basis for meaningful communication in dress. It offers a new understanding of identity formation in Britain and explains the complex relationship between working-class youth-subcultures and Post-War Immigration. The thesis consists of three case studies of the clothes worn by different groups in British society between the period 1965 and 1972: firstly a study of Afro-Caribbean migrants to the UK, secondly the South Asian Diaspora in the UK, and finally the Skinhead youth-subculture. -

Stuart-Hall-Cultural-Identity.Pdf

Questions of Cultural Identity Edited by STUART HALL and PAUL DU GAY SAGE Publications London • Thousand Oaks • New Delhi Editorial selection and matter © Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay, 1996 Chapter 1 ©Stuart Hall, 1996 Chapter 2 © Zygmunt Bauman, 1996 Chapter 3 © Marilyn Strathern, 1996 Chapter 4 © Homi K. Bhabha, 1996 Chapter 5 © Kevin Robins, 1996 Chapter 6 © Lawrence Grossberg, 1996 Chapter 7 © Simon Frith, 19% Chapter 8 © Nikolas Rose, 1996 Chapter 9 © Paul du Gay, 1996 Chapter 10 ©James Donald, 19% First published 1996. Reprinted 1996,1997, 1998,2000,2002, (twice), 2003. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from the Publishers. SAGE Publications Ltd 6 Bonhill Street <D London EC2A 4PU SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd 32, M-Block Market Greater Kailash -1 New Delhi 110 048 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 08039 7882-0 ISBN 0 8039 7883-9 (pbk) Library of Congress catalog record available Typeset by Type Study, Scarborough, North Yorkshire Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Notes on Contributors vii Preface ix 1 Introduction 1 Who Needs 'Identity'? Stuart Hall 2 From Pilgrim to Tourist - or a Short History of Identity 18 Zygmunt Bauman 3 Enabling Identity? 37 Biology, Choice and the New Reproductive Technologies Marilyn Strathern 4 Culture's In-Between 53 HomiK. -

Hall: Butler's Had a Nightmare Camp – I'll Take Him

HALL: BUTLER’S HAD A NIGHTMARE CAMP – I’LL TAKE HIM OUT Stuart Hall believes Paul Butler has had a ‘nightmare’ camp for their rematch and he’ll take advantage by taking him out in their rematch and eliminator for the WBA World Bantamweight title at the Echo Arena in Liverpool on September 30, live on Sky Sports. Hall and Butler first met in May 2014 in Newcastle where Butler took Hall’s IBF crown in a tight contest, and over three years later the 37 year old finally gets the chance to gain revenge and take a big step towards challenging for the WBA title – a belt held by another old foe of Hall’s, Jamie McDonnell, who is set to defend it again in a rematch with Liborio Solis. Both men have since switched trainers since their first encounter, with Hall basing himself in Birmingham with Max McCracken alongside Kal and Gamal Yafai, while Butler has moved into Joe Gallagher’s Bolton home of champions – but Hall says he’s heard that Butler’s camp has been far from ideal, and he’ll take advantage of that to exact his revenge. “My camp has gone brilliantly, I couldn’t ask for better preparation,” said Hall. “I’m training with the Yafai brothers who are world class fighters. “I’ve been told he’s had a nightmare camp, terrible sparring which is not the best to fight someone like me. Deep down it’s my last chance, but I’m not going off that – I’m just going off what I’m doing and I know it will be too much for him. -

Anglistentag 2010 Saarbrücken

Anglistentag 2010 Saarbrücken Anglistentag 2010 Saarbrücken Proceedings edited by Joachim Frenk Lena Steveker Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier Anglistentag 2010 Saarbrücken Proceedings ed. by Joachim Frenk, Lena Steveker Trier: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2011 (Proceedings of the Conference of the German Association of University Teachers of English; Vol. 32) ISBN 978-3-86821-332-4 Umschlaggestaltung: Brigitta Disseldorf © WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2011 ISBN 978-3-86821-332-4 Alle Rechte vorbehalten Nachdruck oder Vervielfältigung nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Verlags Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem und säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier Bergstraße 27, 54295 Trier Postfach 4005, 54230 Trier Tel.: (0651) 41503 / 9943344, Fax: 41504 Internet: http://www.wvttrier.de e-mail: [email protected] Proceedings of the Conference of the German Association of University Teachers of English Volume XXXII Contents Joachim Frenk and Lena Steveker (Saarbrücken) Preface XI Forum: Anglistik und Mediengesellschaft Eckart Voigts-Virchow und Nicola Glaubitz (Siegen) Einleitung 3 Julika Griem (Darmstadt) Überlegungen für eine Anglistik in der Mediengesellschaft: Verfahren, Praxen und Geltungsansprüche 9 Gudula Moritz (Mainz) Anglistik und Mediengesellschaft 13 Nicola Glaubitz (Siegen) Für eine Diskursivierung der Kultur 15 Regula Hohl Trillini (Basel) Don't Worry, Be Trendy: Shakespeares Rezeption als ermutigender Modellfall 19 Eckart Voigts-Virchow (Siegen) Performative Hermeneutik durch mediendiversifizierte -

Mediated Thugs: Re-Reading Stuart Hall's Work on Football Hooliganism

Piskurek: Mediated Thugs 88 Mediated Thugs: Re-reading Stuart Hall’s Work on Football Hooliganism CYPRIAN PISKUREK TU Dortmund University, Germany Introduction Amidst the countless and seminal contributions by Stuart Hall to discourses around race, representation, politics and identity, it is easy to overlook the equally countless essays about ‘minor’ fields in which he covered a broad range of related topics. One of these texts is an article about football hooliganism from 1978, entitled “The Treatment of ‘Football Hooliganism’ in the Press” from a volume edited by Hall and his colleagues Roger Ingham, John Clarke, Peter Marsh and Jim Donovan. The collection of essays is based on a conference held that previous year at the University of Southampton about football fans and violence, a topic that had become a major concern in the British public and that in consequence became a mainstay for research in the field of sociology. As this is Hall’s only text dealing with violence around football, the essay fills only a minor niche in his oeuvre. Within the field of hooligan studies, however, his contribution to the discipline is still seen as an important addition: one of the major textbooks, Football Hooliganism (2005) by Steve Frosdick and Peter Marsh, mentions the ideas put forward in Hall's work as one of six major approaches to the phenomenon. That is remarkable, given that Hall is cited alongside researchers like Eric Dunning, John Williams or Patrick Murphy from the so-called Leicester School or Ian Taylor and others who spent a large part of their working life researching and publishing on the topic. -

Housing Cultural Studies – a Memoir, with Buildings, of Stuart Hall, Richard Hoggart and Terence Hawkes John Hartley

Housing Cultural Studies – A memoir, with buildings, of Stuart Hall, Richard Hoggart and Terence Hawkes John Hartley Curtin University, Australia and Cardiff University, Wales Abstract Three globally significant figures in cultural studies died in 2014. They were Terence Hawkes (13 May 1932-16 January 2014), Stuart Hall (3 February 1932-10 February 2014), and Richard Hoggart (24 September 1918-10 April 2014). I miss them all. That personal feeling motivates what follows. But there’s a public aspect to it too. Not only did I watch and admire these three people building cultural studies; I know the buildings they built it in. Suddenly those buildings feel empty, not facing the future but confined to their times, ceasing to ‘speak’ as they silently await sufficient neglect and dilapidation to justify the new-generation wrecking ball of ‘creative destruction’ to open up the space for something new that has already forgotten them. Keywords: Terence Hawkes, Stuart Hall, Richard Hoggart. ‘Et credis cineres curare sepultos?’ ‘And do you think that the ashes of the dead concern themselves with our affairs?’ (Virgil, in Stone 2013: 174) I am motivated to write about Hall, Hoggart and Hawkes because academic society, the ‘critical’ humanities, and cultural studies in particular, are careless of their elders and ancestors. They – we – are inclined too often to accept a rote-learned genesis (‘… and Hoggart begat Hall…’), which does no honour to those named, never mind the many whose names are quietly erased by this all too ‘selective tradition’ (Williams 1977).1 So another part of my motivation is that I think the memorialisation process always gets things wrong. -

History Workshop Audio Archive Catalogue

HISTORY WORKSHOP AUDIO ARCHIVE (RS 5) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Various, 2020. RS 5 History Workshop Audio Archive 1977-1991 Name of Creator: History Workshop Extent: 130 wav files Administrative/Biographical History: History Workshop was a popular movement for the democratisation of History which flourished in Britain from the late 1960s to the mid 1980s (with sporadic activity continuing into the 1990s). It emerged from Ruskin College Oxford where Raphael Samuel, the movement’s initiator and presiding spirit, taught history for many decades. In the course of the 1970s History Workshop spread across Britain, spawning dozens of regional and local initiatives, publishing many books, pamphlets and journals (including the still-extant History Workshop Journal), and acquiring influence throughout intellectual and educational circles. During these years the movement also went international, spawning sister workshops in Germany, France, Italy, South Africa and America. Its high point was reached in the late 1970s, and thereafter it went into a slow decline, although many of the developments it helped to foster (such as oral history and women’s history) continue to flourish today. The early workshops were Ruskin-based, participant-led events that drew on what Raphael Samuel described as a ‘fluid coalition of worker-students from Ruskin and other socialist historians’. The first one, ‘A Day with the Chartists’, held in 1967, was a modest affair with about 50 in attendance. But five years later a workshop on ‘Workers’ Control’ attracted over 700 and by the mid 1970s the workshops had become major festivals of history, attracting up to a thousand participants. While the themes explored varied widely, the events were primarily a showcase for history seen from a non-elite perspective, ‘people’s history’ as it was labelled. -

The Following Title Bouts Have Been Already Staged in the First Part of the 2018 Season

WBC International Championships - The 2018 season up to August 6th The following title bouts have been already staged in the first part of the 2018 season Sauerland Event 175 Lbs silver Riga, Latvia Yohann Kongolo WUD10 Andrej Pokumeiko Jan 27 Mario Loreni 200 Lbs silver Florence, Italy Fabio TURCHI WTKO1 Dario G. Balmaceda Feb 2 Aram Davtyan 135 Lbs Adler (Soči), Russia Vage Sarykhanyan Lost KO7 Hurricane FUTA Feb 3 Igor Korolev, ABC 154 Lbs silver St Petersburg Russia Nikolozi Tasidis Lost UD10 Evgeny Terentiev Feb 10 J.M.Boucheron 160 Lbs vacant Limoges, France Karin Achour WUD 12 Patrice Sou Toke Feb 10 Rodney Berman 105 Lbs Emperors, RSA Dee Jay Kriel WUD 12 Xolisa Magusha March 3 Rodney Berman 147 Lbs vacant Emperors, RSA Thulani Mbenge WUD 12 Diego Cruz March 3 Ahmet Öner 168 Lbs Köln, Germany Avni Yildirim WUD 12 Dereck Edwards March 3 Ahmet Öner 135 Lbs silver Köln, Germany Robert Tlatlik WKO 7 Marek Jedrzejewsky March 3 Eddie Hearn 122 Lbs Sheffield, UK Gamal Yafai Lost UD12 Gavin McDonnell March 3 Brian Amatruda 175 Lbs vacant Melbourne, AUS Isaac Chilemba WUD12 Blake Caparello March 16 Ken Casey, Murphy 140 Lbs silver Boston, USA Danny O’Connor WUD10 Steve Clagett March 17 Armin Tan 108 Lbs silver Jakarta, IND Tibo Monabesa WUD10 Lester Abutan March 31 Rodney Berman 126 Lbs vacant Emperors, RSA Lerato Dlamini WSD12 Sydney Maluleka April 8 Mario Margossian 130 Lbs silver Mercedes, ARG Horacio Cabral Lost SD10 Pablo Ojeda April 20 Ahmet Öner 168 Lbs Hürth, Germany Avni Yildirim W UD 12 Ryan Ford May 12 Aram Davtyan 126 Lbs silver -

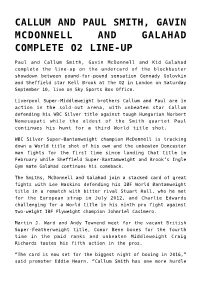

Callum and Paul Smith, Gavin Mcdonnell and Galahad Complete O2 Line-Up

CALLUM AND PAUL SMITH, GAVIN MCDONNELL AND GALAHAD COMPLETE O2 LINE-UP Paul and Callum Smith, Gavin McDonnell and Kid Galahad complete the line-up on the undercard of the blockbuster showdown between pound-for-pound sensation Gennady Golovkin and Sheffield star Kell Brook at The O2 in London on Saturday September 10, live on Sky Sports Box Office. Liverpool Super-Middleweight brothers Callum and Paul are in action in the sold-out arena, with unbeaten star Callum defending his WBC Silver title against tough Hungarian Norbert Nemesapati while the eldest of the Smith quartet Paul continues his hunt for a third World title shot. WBC Silver Super-Bantamweight champion McDonnell is tracking down a World title shot of his own and the unbeaten Doncaster man fights for the first time since landing that title in February while Sheffield Super-Bantamweight and Brook’s Ingle Gym mate Galahad continues his comeback. The Smiths, McDonnell and Galahad join a stacked card of great fights with Lee Haskins defending his IBF World Bantamweight title in a rematch with bitter rival Stuart Hall, who he met for the European strap in July 2012, and Charlie Edwards challenging for a World title in his ninth pro fight against two-weight IBF Flyweight champion Johnriel Casimero. Martin J. Ward and Andy Townend meet for the vacant British Super-Featherweight title, Conor Benn boxes for the fourth time in the paid ranks and unbeaten Middleweight Craig Richards tastes his fifth action in the pros. “The card is now set for the biggest night of boxing in 2016,” said promoter Eddie Hearn. -

World Boxing Council R a T I N G S

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2016 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2016 WORLD BOXING COUNCIL / CONSEJO MUNDIAL DE BOXEO COMITE DE CLASIFICACIONES / RATINGS COMMITTEE WBC Adress: Cuzco # 872, Col. Lindavista 07300 – México D.F., México Telephones: (525) 5119-5274 / 5119-5276 – Fax (525) 5119-5293 E-mail: [email protected] RATINGS RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2016 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2016 HEAVYWEIGHT (+200 - +90.71) CHAMPION: DEONTAY WILDER (US) EMERITUS CHAMPION: VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: January 17, 2015 LAST DEFENCE: July 16, 2016 LAST COMPULSORY: January 17, 2015 WBA CHAMPION: Tyson Fury (GB) IBF CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) WBO CHAMPION: Tyson Fury (GB) Contenders: WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Johann Duhaupas (France) WBC INT. CHAMPION: Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) 1 Alexander Povetkin (Russia) * CBP * CLEAN BOXING PROGRAM 2 Bermane Stiverne (Haiti/Canada) 3 Kubrat Pulev (Bulgaria) EBU 4 Joseph Parker (New Zealand) OPBF 5 David Haye (GB) 6 Johann Duhaupas (France) SILVER 7 Andy Ruiz (Mexico) NABF 8 Bryant Jennings (US) 9 Malik Scott (US) 10 Eric Molina (US) 11 Gerald Washington (US) 12 Carlos Takam (Cameroon) 13 Mariusz Wach (Poland) 14 Dereck Chisora (GB) 15 Jarrell Miller (US) 16 Kyotaro Fujimoto (Japan) 17 Andrzej Wawrzyk (Poland) 18 David Price (GB) 19 Chris Arreola (US) 20 Alexander Dimitrenko (Russia) 21 Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) INTL 22 Dominic Breazeale (US) 23 Andriy Rudenko (Ukraine) INTL Silver 24 Charles Martin (US) 25 Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) 26 Francesco -

EBU Ratings August 2013

EBU Ratings August 2013 President Mr Bob Logist Chairman Mr Pertti Augustin In collaboration with: Board of Directors Techincal Advisors: Mr Eric Armit Mr Michele Schiavone Ratings referred to all the fights up to August 2013 HEAVYWEIGHTS (over 90,719 kg) CRUISERWEIGHTS (up to 90,719 kg) LIGHT-HEAVYWEIGHTS (up to 79,379 kg) VACANT TITLE * Champ:Mateusz MASTERNAK (PDec 15, 2012 * Champ: Juergen BRAEHMER (DE/AT) Feb 2, 2013 * Chall: Derek CHISORA (GB) * Chall : Jeremy OUANNA (FR) * Chall: Tony BELLEW (GB) * Chall: Edmund GERBER (DE) EU: Richard TOWERS (GB) EU: Mirko LARGHETTI (IT) EU: Vacant EEEU: Vacant EEEU: Vacant EEEU: Vacant Contenders: Contenders: Contenders: 1 Kubrat PULEV (BG/AT) 1 Denis LEBEDEV (RU) 1 Nathan CLEVERLY (GB) 2 Robert HELENIUS (FI) 2 Ola AFOLABI (GB/DE) 2 Eduard GUTKNECHT (DE) 3 Tyson FURY (GB) 3 Firat ARSLAN (DE) 3 Dmitri SUKHOTSKY (RU) 4 Denis BOYTSOV (RU) 4 Rakhim CHAKHKIEV (RU) 4 Nadjib MOHAMMEDI (FR) 5 Richard TOWERS (GB) EU Champion 5 Mirko LARGHETTI (IT) EU Champion 5 Orial KOLAJ (IT) 6 Alexander DIMITRENKO (DE) 6 Alexander ALEKSEEV (RU/DE) 6 Robert WOGE (DE) 7 Artur SZPILKA (PL) 7 Giacobbe FRAGOMENI (IT) 7 Igor MICHALKIN (RU) 8 Francesco PIANETA (IT/DE) 8 Grigory DROZD (RU) 8 Oleksander CHERVYAK (UA) 9 David PRICE (GB) 9 Silvio BRANCO (IT) 9 Vyacheslav UZELKOV (UA) 10 Alexander USTINOV (BY/UA) 10 Pawel KOLODZEJ (PL) 10 Enzo MACCARINELLI (GB) 11 Erkan TEPER (DE) 11 Krzystof GLOWACKI (PL) 11 Dariusz SEK (PL) 12 Andrzej WAWRZYK (PL) 12 Dmytro KUCHER (UA) 12 Stefano ABATANGELO (IT) 13 Johann DUHAUPAS (FR) 13 Juho -

Bibliography: Books 1992-2012

Museum Studies, Museology, Museography, Museum Architecture, Exhibition Design Bibliography: Books 1992-2012 Luca Basso Peressut (ed.) Updated January 2012 2 Sections: p. 3 Introduction p. 4 General Readers, Anthologies, and Dictionaries p. 18 The Idea of Museum: Historical Perspectives p. 38 Museums Today: Debate and Studies on Major Issues p. 97 Making History and Memory in Museums p. 103 Museums: National, Transnational, and Global Perspectives p. 116 Representing Cultures in Museums: From Colonial to Postcolonial p. 124 Museums and Communities p. 131 Museums, Heritage, and Territory p. 144 Museums: Identity, Difference and Social Equality p. 150 ‘Hot’ and Difficult Topics and Histories in Museums p. 162 Collections, Objects, Material Culture p. 179 Museum and Publics: Interpretation, Learning, Education p. 201 Museums in a digital age: ICT, virtuality, new media p. 211 Museography, Exhibitions: Cultural Debate and Design p. 247 Museum Architecture: Theory and Practice p. 266 Contemporary Art, Artists and Museums: Investigations, Theories, Actions p. 279 Museums and Libraries Partnership Updated January 2012 3 Introduction This bibliography is intended as a general overview of the printed books on museums topics published in English, French, German, Spanish and Italian in Europe and the United States over the last twenty years or so. The chosen period (1992-2012) is only apparently arbitrary, since this is the period of major output of studies and research in the rapidly changing contemporary museum field. The 80s of the last century began with the affirmation of the schools of ‘museum studies’ in the Anglophone countries, as well as with the development of the Nouvelle Muséologie in France (consolidated in 1985 with the foundation of the Mouvement International pour la Nouvelle Muséologie-MINOM, as an ICOM affiliate).