Stuart Hall and Black British Art 62

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CVAN Open Letter to the Secretary of State for Education

Press Release: Wednesday 12 May 2021 Leading UK contemporary visual arts institutions and art schools unite against proposed government cuts to arts education ● Directors of BALTIC, Hayward Gallery, MiMA, Serpentine, Tate, The Slade, Central St. Martin’s and Goldsmiths among over 300 signatories of open letter to Education Secretary Gavin Williamson opposing 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects in higher education ● The letter is part of the nationwide #ArtIsEssential campaign to demonstrate the essential value of the visual arts This morning, the UK’s Contemporary Visual Arts Network (CVAN) have brought together leaders from across the visual arts sector including arts institutions, art schools, galleries and universities across the country, to issue an open letter to Gavin Williamson, the Secretary of State for Education asking him to revoke his proposed 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects across higher education. Following the closure of the consultation on this proposed move on Thursday 6th May, the Government has until mid-June to come to a decision on the future of funding for the arts in higher education – and the sector aims to remind them not only of the critical value of the arts to the UK’s economy, but the essential role they play in the long term cultural infrastructure, creative ambition and wellbeing of the nation. Working in partnership with the UK’s Visual Arts Alliance (VAA) and London Art School Alliance (LASA) to galvanise the sector in their united response, the CVAN’s open letter emphasises that art is essential to the growth of the country. -

Read the Introduction

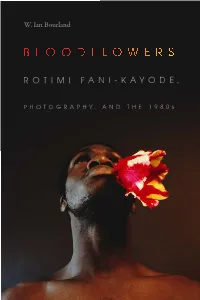

BLOODFLOWERS The Visual Arts of Africa and Its Diasporas A series edited by Kellie Jones and Steven Nelson ii / Exposure One W. Ian Bourland BLOODFLOWERS ROTIMI FANI- KAYODE, PHOTOGRAPHY, AND THE 1980S Duke University Press / Durham and London / 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bourland, W. Ian, [date] author. Title: Bloodfl owers : Rotimi Fani-Kayode, photography, and the 1980s / W. Ian Bourland. Other titles: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, photography, and the 1980s Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: The visual arts of Africa and its diasporas | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers:lccn 2018032576 (print) lccn 2018037542 (ebook) isbn 9781478002369 (ebook) isbn 9781478000686 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478000891 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Fani-Kayode, Rotimi, 1955 – 1989 — Criticism and interpretation. | Photography of men. | Photography of the nude. | Homosexuality in art. | Gay erotic photography. | Photographers — Nigeria. | Photography — Social aspects. Classifi cation:lcc tr681.m4 (ebook) | lcc tr681.m4 b68 2019 (print) | ddc 779/.21 — dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018032576 Frontispiece: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled (1985). © Rotimi Fani-Kayode / Autograph abp. Courtesy of Autograph abp. Cover art: Rotimi Fani- Kayode, Tulip Boy -

Stuart Hall Bibliography 27-02-2018

Stuart Hall (3 February 1932 – 10 February 2014) Editor — Universities & Left Review, 1957–1959. — New Left Review, 1960–1961. — Soundings, 1995–2014. Publications (in chronological order) (1953–2014) Publications are given in the following order: sole authored works first, in alphabetical order. Joint authored works are then listed, marked ‘with’, and listed in order of co- author’s surname, and then in alphabetical order. Audio-visual material includes radio and television broadcasts (listed by date of first transmission), and film (listed by date of first showing). 1953 — ‘Our Literary Heritage’, The Daily Gleaner, (3 January 1953), p.? 1955 — ‘Lamming, Selvon and Some Trends in the West Indian Novel’, Bim, vol. 6, no. 23 (December 1955), 172–78. — ‘Two Poems’ [‘London: Impasse by Vauxhall Bridge’ and ‘Impasse: Cities to Music Perhaps’], BIM, vol. 6, no. 23 (December 1955), 150–151. 1956 — ‘Crisis of Conscience’, Oxford Clarion, vol. 1, no. 2 (Trinity Term 1956), 6–9. — ‘The Ground is Boggy in Left Field!’ Oxford Clarion, vol. 1, no 3 (Michaelmas Term, 1956), 10–12. 1 — ‘Oh, Young Men’ (Extract from “New Landscapes for Aereas”), in Edna Manley (ed.), Focus: Jamaica, 1956 (Kingston/Mona: The Extra-Mural Department of University College of the West Indies, 1956), p. 181. — ‘Thus, At the Crossroads’ (Extract from “New Landscapes for Aereas”), in Edna Manley (ed.), Focus: Jamaica, 1956 (Kingston/Mona: The Extra-Mural Department of University College of the West Indies, 1956), p. 180. — with executive members of the Oxford Union Society, ‘Letter: Christmas Card Aid’, The Times, no. 53709 (8 December 1956), 7. 1957 — ‘Editorial: “Revaluations”’, Oxford Clarion: Journal of the Oxford University Labour Club, vol. -

For Immediate Release Isaac Julien

For immediate release Isaac Julien - Vintage April 22 – June 11, 2016 Opening reception: April 22, 6-8pm Jessica Silverman Gallery is pleased to present “Vintage,” a show of early photographs by Isaac Julien. The exhibition presents three bodies of work - Looking for Langston (1989), Trussed (1996) and The Long Road to Mazatlan (1999-2000). Isaac Julien’s artistic practice is rooted in photography. Looking for Langston is an homage to Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. When Julien was preparing to make what would become this award- winning work, he studied the photographs of James Van der Zee, George Platt Lynes and Robert Mapplethorpe. His research led not only to a critical response to their work but the creation of a landmark in the exploration of desire and the reciprocity of the gaze. Throughout his career, Julien has worked simultaneously with photographers and cinematographers to make still and moving picture artworks. For Julien, the photographs act as “memorial sites.” Sometimes they reveal facts behind his fictions and explore the creative process, other times they zero in on a portrait or go deeper into a moment of contested history. Whatever the case, Julien is unapologetic about his pursuit of beauty. Visual pleasure is essential to his exploration of subaltern issues and so he often works with advanced pre- and post-production technologies to orchestrate what he calls an “aesthetics of reparation.” The three photographic series included in the exhibition are vintage in several senses of the word. Working with Nina Kellgren (cinematographer) and Sunil Gupta (photographer), Julien shot Looking for Langston in the 1980s in London but set it in the jazz world of 1920s Harlem. -

A Listening Eye: the Films of Mike Dibb Part Three: Conversation Pieces

A Listening Eye: The Films of Mike Dibb Part Three: Conversation Pieces Week Two Available to view 5 - 11 March 2021 For the ninth week of A Listening Eye, as we move further into the final phase of Mike Dibb’s series, we focus on his dynamic films about and with writers, thinkers, activists and public intellectuals, as well as an artist or two. This programme continues to demonstrate the sheer range of engaged lives and ideas that Dibb has documented. Available to view 5 - 11 March: The Further Adventures of Don Quixote, 1995, 50’ The Beginning of the End of the Affair, 1999, 50’ Memories of the Future, John Ruskin and William Morris 1984, 2x52’ A Curious Mind – AS Byatt, 1996, 50’ Somewhere Over the Rainbow, 1982, 50’ Steven Rose – A Profile 2003, 30’ The Spirit of Lorca, 1986, 75’ The Fame and Shame of Salvador Dali, 1997-98, 120’ The Further Adventures of Don Quixote (Bookmark) As early as chapter two in this astonishingly original and prescient novel, Miguel de Cervantes was already aware of his hero’s impending immortality: “Happy shall be the times and happy shall be the age, in which my famous deeds shall come to light; deeds worthy to be engraved in bronZe, carved in marble, and re-created in painting, as a monument to posterity!” Cervantes’ clairvoyance didn’t quite stretch to the arrival of cinema and television; but I’m sure that, if he had known about them, he would have guessed that a film about Don Quixote and Sancho Panza’s astonishing after-life would eventually be made. -

PROGRAM SESSIONS Madison Suite, 2Nd Floor, Hilton New York Chairs: Karen K

Wednesday the Afterlife of Cubism PROGrAM SeSSIONS Madison Suite, 2nd Floor, Hilton New York Chairs: Karen K. Butler, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Wednesday, February 9 Washington University in St. Louis; Paul Galvez, University of Texas, Dallas 7:30–9:00 AM European Cubism and Parisian Exceptionalism: The Cubist Art Historians Interested in Pedagogy and Technology Epoch Revisited business Meeting David Cottington, Kingston University, London Gibson Room, 2nd Floor Reading Juan Gris Harry Cooper, National Gallery of Art Wednesday, February 9 At War with Abstraction: Léger’s Cubism in the 1920s Megan Heuer, Princeton University 9:30 AM–12:00 PM Sonia Delaunay-Terk and the Culture of Cubism exhibiting the renaissance, 1850–1950 Alexandra Schwartz, Montclair Art Museum Clinton Suite, 2nd Floor, Hilton New York The Beholder before the Picture: Miró after Cubism Chairs: Cristelle Baskins, Tufts University; Alan Chong, Asian Charles Palermo, College of William and Mary Civilizations Museum World’s Fairs and the Renaissance Revival in Furniture, 1851–1878 Series and Sequence: the fine Art print folio and David Raizman, Drexel University Artist’s book as Sites of inquiry Exhibiting Spain at the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 Petit Trianon, 3rd Floor, Hilton New York M. Elizabeth Boone, University of Alberta Chair: Paul Coldwell, University of the Arts London The Rétrospective and the Renaissance: Changing Views of the Past Reading and Repetition in Henri Matisse’s Livres d’artiste at the Paris Expositions Universelles Kathryn Brown, Tilburg University Virginia Brilliant, John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Hey There, Kitty-Cat: Thinking through Seriality in Warhol’s Early The Italian Exhibition at Burlington House Artist’s Books Andrée Hayum, Fordham University Emerita Lucy Mulroney, University of Rochester Falling Apart: Fred Sandback at the Kunstraum Munich Edward A. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio magazine Board of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer Creative Director The Studio Museum in Harlem is sup- Thelma Golden Dr. Anita Blanchard ported, in part, with public funds provided Jacqueline L. Bradley Managing Editor by the following government agencies and Valentino D. Carlotti Dana Liss elected representatives: Kathryn C. Chenault Joan S. Davidson Copy Editor The New York City Department of Cultural Gordon J. Davis, Esq. Samir S. Patel Aairs; New York State Council on the Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Arts, a state agency; National Endowment Design Sandra Grymes for the Arts; the New York City Council; Pentagram Arthur J. Humphrey Jr. and the Manhattan Borough President. George L. Knox Printing Nancy L. Lane Allied Printing Services The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Dr. Michael L. Lomax grateful to the following institutional do- Original Design Concept Bernard I. Lumpkin nors for their leadership support: 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi Ann G. Tenenbaum Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies John T. Thompson by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Booth Ferris Foundation Reginald Van Lee 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027. Ed Bradley Family Foundation The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Hon. Bill de Blasio, ex-oicio Copyright ©2015 Studio magazine. Charitable Trust Hon. Tom Finkelpearl, ex-oicio Ford Foundation All rights, including translation into other The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation languages, are reserved by the publisher. -

Clothes, Immigration and Youth Identities in Britain 1965-1972

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository DRESSING RACE: CLOTHES, IMMIGRATION AND YOUTH IDENTITIES IN BRITAIN 1965-1972 by SAM HUMPHRIES A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Modern and Contemporary History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis will explore the role race plays in conceptions and performances of British identity by using clothes as a source. It will use the relationship between the body and clothes to argue that cultural understandings of race are part of the basis for meaningful communication in dress. It offers a new understanding of identity formation in Britain and explains the complex relationship between working-class youth-subcultures and Post-War Immigration. The thesis consists of three case studies of the clothes worn by different groups in British society between the period 1965 and 1972: firstly a study of Afro-Caribbean migrants to the UK, secondly the South Asian Diaspora in the UK, and finally the Skinhead youth-subculture. -

Historical Argument and Practice Bibliography for Lectures 2019-20

HISTORICAL ARGUMENT AND PRACTICE BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR LECTURES 2019-20 Useful Websites http://www.besthistorysites.net http://tigger.uic.edu/~rjensen/index.html http://www.jstor.org [e-journal articles] http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/ejournals_list/ [all e-journals can be accessed from here] http://www.historyandpolicy.org General Reading Ernst Breisach, Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983) R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1946) Donald R. Kelley, Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998) Donald R. Kelley, Fortunes of History: Historical Inquiry from Herder to Huizinga (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003) R. J. Evans, In Defence of History (2nd edn., London, 2001). E. H. Carr, What is History? (40th anniversary edn., London, 2001). Forum on Transnational History, American Historical Review, December 2006, pp1443-164. G.R. Elton, The Practice of History (2nd edn., Oxford, 2002). K. Jenkins, Rethinking History (London, 1991). C. Geertz, Local Knowledge (New York, 1983) M. Collis and S. Lukes, eds., Rationality and Relativism (London, 1982) D. Papineau, For Science in the Social Sciences (London, 1978) U. Rublack ed., A Concise Companion to History (Oxford, 2011) Q.R.D. Skinner, Visions of Politics Vol. 1: Regarding Method (Cambridge, 2002) David Cannadine, What is History Now, ed. (Basingstoke, 2000). -----------------------INTRODUCTION TO HISTORIOGRAPHY---------------------- Thu. 10 Oct. Who does history? Prof John Arnold J. H. Arnold, History: A Very Short Introduction (2000), particularly chapters 2 and 3 S. Berger, H. Feldner & K. Passmore, eds, Writing History: Theory & Practice (2003) P. -

Stuart-Hall-Cultural-Identity.Pdf

Questions of Cultural Identity Edited by STUART HALL and PAUL DU GAY SAGE Publications London • Thousand Oaks • New Delhi Editorial selection and matter © Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay, 1996 Chapter 1 ©Stuart Hall, 1996 Chapter 2 © Zygmunt Bauman, 1996 Chapter 3 © Marilyn Strathern, 1996 Chapter 4 © Homi K. Bhabha, 1996 Chapter 5 © Kevin Robins, 1996 Chapter 6 © Lawrence Grossberg, 1996 Chapter 7 © Simon Frith, 19% Chapter 8 © Nikolas Rose, 1996 Chapter 9 © Paul du Gay, 1996 Chapter 10 ©James Donald, 19% First published 1996. Reprinted 1996,1997, 1998,2000,2002, (twice), 2003. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from the Publishers. SAGE Publications Ltd 6 Bonhill Street <D London EC2A 4PU SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd 32, M-Block Market Greater Kailash -1 New Delhi 110 048 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 08039 7882-0 ISBN 0 8039 7883-9 (pbk) Library of Congress catalog record available Typeset by Type Study, Scarborough, North Yorkshire Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Notes on Contributors vii Preface ix 1 Introduction 1 Who Needs 'Identity'? Stuart Hall 2 From Pilgrim to Tourist - or a Short History of Identity 18 Zygmunt Bauman 3 Enabling Identity? 37 Biology, Choice and the New Reproductive Technologies Marilyn Strathern 4 Culture's In-Between 53 HomiK. -

Gunn-Vernon Cover Sheet Escholarship.Indd

UC Berkeley GAIA Books Title The Peculiarities of Liberal Modernity in Imperial Britain Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6wj6r222 Journal GAIA Books, 21 ISBN 9780984590957 Authors Gunn, Simon Vernon, James Publication Date 2011-03-15 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Peculiarities of Liberal Modernity in Imperial Britain Edited by Simon Gunn and James Vernon Published in association with the University of California Press “A remarkable achievement. This ambitious and challenging collection of tightly interwoven essays will find an eager au- dience among students and faculty in British and imperial history, as well as those interested in liberalism and moder- nity in other parts of the world.” Jordanna BaILkIn, author of The Culture of Property: The Crisis of Liberalism in Modern Britain “This volume investigates no less than the relationship of liberalism to Britain’s rise as an empire and the first modern nation. In its global scope and with its broad historical perspective, it makes a strong case for why British history still matters. It will be central for anyone interested in understanding how modernity came about.” Frank TrenTMann, author of Free Trade Nation: Consumption, Commerce, and Civil Society in Modern Britain In this wide-ranging volume, leading scholars across several disciplines—history, literature, sociology, and cultural studies—investigate the nature of liberalism and modernity in imperial Britain since the eighteenth century. They show how Britain’s liberal version of modernity (of capitalism, democracy, and imperialism) was the product of a peculiar set of historical cir- cumstances that continues to haunt our neoliberal present. -

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006 BECAUSE FILMS INSPIRE... WONDER There’s more to discover about film and television British Film Institute through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning Report & Financial resources are here to inspire you. Statements 2006 Contents The mission about the BFI 3 Great expectations Governors’ report 5 Out of the past Archive strategy 7 Walkabout Cultural programme 9 Modern times Director’s report 17 The commitments key aims for 2005/06 19 Performance Financial report 23 Guys and dolls how the BFI is governed 29 Last orders Auditors’ report 37 The full monty appendices 57 The mission ABOUT THE BFI The BFI (British Film Institute) was established in 1933 to promote greater understanding, appreciation and access to fi lm and television culture in Britain. In 1983 The Institute was incorporated by Royal Charter, a copy of which is available on request. Our mission is ‘to champion moving image culture in all its richness and diversity, across the UK, for the benefi t of as wide an audience as possible, to create and encourage debate.’ SUMMARY OF ROYAL CHARTER OBJECTIVES: > To establish, care for and develop collections refl ecting the moving image history and heritage of the United Kingdom; > To encourage the development of the art of fi lm, television and the moving image throughout the United Kingdom; > To promote the use of fi lm and television culture as a record of contemporary life and manners; > To promote access to and appreciation of the widest possible range of British and world cinema; and > To promote education about fi lm, television and the moving image generally, and their impact on society.