FILMING for CHANGE: the Art of Influencing Public Policy Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

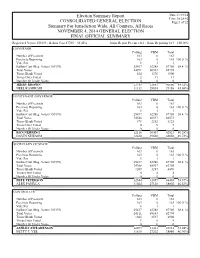

Gems Election Summary Report

Election Summary Report Date:11/19/14 Time:10:28:42 CONSOLIDATED GENERAL ELECTION Page:1 of 22 Summary For Jurisdiction Wide, All Counters, All Races NOVEMBER 4, 2014 GENERAL ELECTION FINAL OFFICIAL SUMMARY Registered Voters 150139 - Ballots Cast 87705 58.42% Num. Report Precinct 163 - Num. Reporting 163 100.00% GOVERNOR Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. Voters 150139) 25417 62288 87705 58.4 % Total Votes 24891 60901 85792 Times Blank Voted 524 1376 1900 Times Over Voted 2 11 13 Number Of Under Votes 0 0 0 JERRY BROWN 13759 32847 46606 54.32% NEEL KASHKARI 11132 28054 39186 45.68% LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. Voters 150139) 25417 62288 87705 58.4 % Total Votes 24546 60027 84573 Times Blank Voted 871 2252 3123 Times Over Voted 0 9 9 Number Of Under Votes 0 0 0 RON NEHRING 12116 30407 42523 50.28% GAVIN NEWSOM 12430 29620 42050 49.72% SECRETARY OF STATE Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. Voters 150139) 25417 62288 87705 58.4 % Total Votes 24208 58997 83205 Times Blank Voted 1209 3287 4496 Times Over Voted 0 4 4 Number Of Under Votes 0 0 0 PETE PETERSON 12544 31859 44403 53.37% ALEX PADILLA 11664 27138 38802 46.63% CONTROLLER Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. -

Sample Ballot Continued…

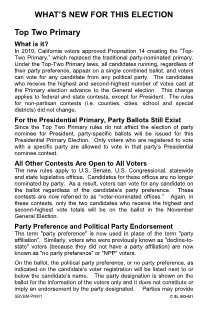

WHAT’S NEW FOR THIS ELECTION Top Two Primary What is it? In 2010, California voters approved Proposition 14 creating the “Top- Two Primary,” which replaced the traditional party-nominated primary. Under the Top-Two Primary laws, all candidates running, regardless of their party preference, appear on a single combined ballot, and voters can vote for any candidate from any political party. The candidates who receive the highest and second-highest number of votes cast at the Primary election advance to the General election. This change applies to federal and state contests, except for President. The rules for non-partisan contests (i.e. counties, cities, school and special districts) did not change. For the Presidential Primary, Party Ballots Still Exist Since the Top Two Primary rules do not affect the election of party nominee for President, party-specific ballots will be issued for this Presidential Primary Election. Only voters who are registered to vote with a specific party are allowed to vote in that party’s Presidential nominee contest. All Other Contests Are Open to All Voters The new rules apply to U.S. Senate, U.S. Congressional, statewide and state legislative offices. Candidates for these offices are no longer nominated by party. As a result, voters can vote for any candidate on the ballot regardless of the candidate’s party preference. These contests are now referred to as “voter-nominated offices.” Again, in these contests, only the two candidates who receive the highest and second-highest vote totals will be on the ballot in the November General Election. Party Preference and Political Party Endorsement The term "party preference" is now used in place of the term "party affiliation”. -

YES on Proposition 51

YES on Proposition 51 (As of 8/4/16) Organizations California Association of School Business Officials California County Superintendents Educational Services Association California Democratic Party California Nevada Cement Association California Housing Consortium California Republican Party California Retired Teachers Association California School Boards Association California School Nurses Organization California State Firefighters’ Association California State PTA California Taxpayers Association California Young Democrats Central Valley Education Coalition Community College League of California Construction Management Association of America, Southern California Chapter Contractors Association of Truckee Tahoe County School Facilities Consortium Democratic Party of the San Fernando Valley Faculty Association of California Community Colleges League of Women Voters of California Los Angeles County Democratic Party National Electrical Contractors Association, Northern California Chapter Rural Community Assistance Corporation School Energy Coalition School Services of California, Inc. Small School Districts’ Association Statewide Educational Wrap Up Program Western Manufactured Housing Communities Association American Council of Engineering Companies, California American Institute of Architects, California Council Associated General Contractors of California Association of California Construction Managers California Apartment Association Statewide Leaders and Elected Officials Gavin Newsom, Lieutenant Governor of California Tom Torlakson, -

New Assemblymembers.Pages

Client Brief: New Legislators Profiles - 2017-18 Assemblymember Cecilia Aguiar-Curry (D - Davis) 4th District As the first woman mayor of Winters, Cecilia Aguiar-Curry worked to secure computers for every 6th-grader in the city, bridge the digital divide by bringing broadband to rural communities, build a state of the art senior housing development, and establish an Ag innovation hub in Yolo County. She also helped bring a $75 million PG&E training facility to Winters and worked to establish the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument, to protect environmental lands across five counties. She is Chair of the Yolo Housing Commission, Vice-Chair of the Yolo County Water Association, and serves on the Board of Directors of the Sacramento Council of Governments. Aguiar-Curry earned degrees in business administration and accounting from San Jose State University, after which she launched a consulting firm specializing in water, public policy, and community outreach. Previously, she was chosen as one of Congressman John Garamendi’s “Women of the Year” in 2015. Preceded By: Bill Dodd (D) Counties: Colusa (p), Lake (p), Napa, Solano (p), Sonoma (p), Yolo (p) Major Cities: American Canyon, Calistoga, Clearlake, Davis, Dixon, Lakeport, Napa, Rohnert Park, St. Helena, Williams, Winters, Woodland, Yountville Supported By: EdVoice, Jobs PAC Opposed By: CA Federation of Teachers website link www.capitoladvisors.org Page 1! of 22! ! Client Brief: New Legislators Profiles - 2017-18 Assemblymember Kevin Kiley (R - El Dorado Hills) 6th District After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in social studies from Harvard University, Kevin Kiley taught 10th grade English at a high school in South Central Los Angeles. -

2011 Political Contributions and Related Activity Report

Political Contributions & Related Activity Report 2011 CARTER BECK JOHN JESSER DAVID KRETSCHMER SVP & Counsel VP, Provider Engagement & COC SVP, Treasurer & Chief Investment Officer ANDREW LANG LISA LATTS SVP, Chief Information Officer Staff VP, Public Health Policy JACKIE MACIAS VP & General Manager MIKE MELLOH DEB MOESSNER State Sponsored Business 2011 WellPAC VP, Human Resources President & General Manager KY TRACY WINN Board of Directors JOHN WILLEY ANDREW MORRISON Manager, Public Affairs Director, Government Relations SVP, Public Affairs WellPAC Assistant Treasurer & WellPAC Treasurer WellPAC Chairman Executive Director ALAN ALBRIGHT Legal Counsel to WellPAC 1 from the Chairman One way WellPoint is capitalizing on new opportunities to drive growth for the company is by helping to shape the changing marketplace—and this extends to the public policy arena as well. Public policy decisions have a significant impact on our customers and on our operating environment, and that’s why we are committed to playing an active role in discussions that affect the health insurance marketplace. We also regularly seek to help elect candidates to federal and state office who will participate in that dialogue with us through direct advocacy, policy development, lawful corporate contributions and the sponsorship of WellPAC, the non-partisan political action committee of WellPoint associates. What makes WellPAC’s success possible is the voluntary financial support of more than 1,875 WellPoint associates. Our donations enable WellPAC to give contributions directly to the campaigns of state and federal candidates to express our positions. Our Public Affairs team has been actively engaged with lawmakers and candidates at the federal level and in our 14 core business states throughout 2011. -

'Hooting for Houry'

MARCH 19, 2016 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVI, NO. 35, Issue 4429 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF MP Garo Paylan Confidential Demands Freedom of Document Worship for Minorities ISTANBUL (Armenpress) — Turkish-Armenian Garo Targeting Hrant Paylan, a member of the Turkish Parliament as a representative of the People’s Democratic Party, defended the right to freedom of worship for reli- Dink in 1990s gious minorities in the country during the regular session of parliament. Exposed Demokrathaber.net reported that Paylan last week accused the Turkish authorities of infringing ISTANBUL (Armenpress) — Procedural upon the rights to worship of Christians and other instruments of Hrant Dink’s case reveal minorities. striking details on the participation of the “We all, including me, pay taxes, Christians, state, particularly the police and intelli- Muslims, Alevis, everybody professing some reli- gence services, in the murder of the gion pay taxes. But the Directorate for Religious Affairs serves only one religion and one sect of it,” he said. He referred also to the comments of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has said previously that “he wishes for a religious society.” Paylan inquired why, in that case, are religious schools not Houry Gebeshian at the European championships in France, April 2015 opened. “This means Christians have no right to be reli- gious? Why? Why should the religious school of ‘Hooting for Houry’ the Armenian Patriarchate be closed?” he asked. Battle for Armenian WATERTOWN Striving to By Aram Arkun — Armenian Patriarchate Rages on Mirror-Spectator Staff women in the Be the First Hrant Dink Soviet Union ISTANBUL (Daily Sabah) — A Turkish court’s deci- were trained as Female sion to appoint the mother of ailing Armenian professional gymnasts, but after the indepen- Patriarch Mesrob II Mutafyan as his custodian, has revived the long-standing debate over his potential Istanbul-Armenian journalist. -

Aimpoint Press Kit V2

COMPANY INFORMATION AimPoint, Inc. was created to assist companies, political campaigns, trade associations and not-for-profits with the growing demand for financial resources and advocacy. To maximize resources and service, AimPoint, Inc.’s partners merged over 30 years combined experience in fundraising and legislative event management. There are numerous fundraising companies and political consultants across California, but none can match AimPoint’s combination of talented professionals with statewide expertise and a top-to-bottom team approach to delivering client success. • Aimpoint, Inc. was founded in May 2007 by company partners Justin and Michelle Matheson and Beth Holder • Office locations in Northern and Southern California provide AimPoint clients a geographical advantage as professional relationships are developed and maintained across the entire state • AimPoint, Inc. utilizes the most sophisticated computer and internet-based programs to ensure exact targeting and the most current donor databases • In an effort to evolve and adapt with a social environment that is increasingly technologically based, AimPoint, Inc. uses numerous social networking services to increase awareness and advocate both clients and company services alike • AimPoint, Inc. employs a skilled staff of individuals who adhere to the highest standards of ethics and professionalism • Partners and staff at AimPoint have worked on numerous high-profile campaigns such as Mike Huckabee for U.S. President and Steve Poizner for Governor of California • In 2010 -

Ballot Type 12

OFFICIAL BALLOT NOVEMBER 4, 2014 CONSOLIDATED GENERAL ELECTION SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTERS: To vote, fill in the oval like this: Vote both sides of the card. To vote for or against candidates for Associate Justice of the Supreme Court; Presiding Justice, Court of Appeal; or Associate Justice, Court of Appeal, fill in the OVAL next to the word "Yes" or "No," respectively. To vote for any other candidate of your choice, fill in the OVAL next to the candidate's name. Do not vote for more than the number of candidates allowed. To vote for a qualified write-in candidate, write in the candidate's full name on the Write-In line and fill in the OVAL next to it. To vote on a measure, fill in the OVAL next to the word "Yes" or the word "No". If you tear, deface or wrongly mark this ballot, return it to the Elections Official and get another. VOTER-NOMINATED AND NONPARTISAN OFFICES All voters, regardless of the party preference they disclosed upon registration, or refusal to disclose a party preference, may vote for any candidate for a voter-nominated or nonpartisan office. The party preference, if any, designated by a candidate for a voter-nominated office is selected by the candidate and is shown for the information of the voters only. It does not imply that the candidate is nominated or endorsed by the party or that the party approves of the candidate. The party preference, if any, of a candidate for a nonpartisan office does not appear on the ballot. -

Agenda California Authority of Racing Fairs Board of Directors Meeting John Alkire, Chair 12:30 P.M., Tuesday, February 5, 2013

1776 Tribute Road, Suite 205 Sacramento, CA 95815 Office: 916.927.7223 Fax: 916.263.3341 www.calfairs.com AGENDA CALIFORNIA AUTHORITY OF RACING FAIRS BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING JOHN ALKIRE, CHAIR 12:30 P.M., TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2013 Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the California Authority of Racing Fairs’ Board of Directors will commence at 12:30 p.m., Tuesday, February 5, 2013. The meeting will be held in Sacramento. 1776 Tribute Road Conference Room, Sacramento, CA 95815 AGENDA I. Date, time and location of next meeting: March 5, 2013 II. Approval of minutes. III. Report, discussion and action, if any, on Legislative Program. IV. Report, discussion and action, if any, on Sonoma County Fair use of CARF Management Services in 2013. V. Report, discussion and action, if any, on CARF policies regarding security agreement for moneys owed the Agency by Member Fairs. VI. Report, discussion and action, if any, on overpayments from CARF Consolidated Purse Account in 2012. VII. Discussion and action, if any, on financial reports on purses and Parimutuel commissions at racing fairs in 2012. VIII. Financials IX. Executive Director’s Report CALIFORNIA AUTHORITY OF RACING FAIRS 1776 Tribute Road, Suite 205 Sacramento, CA 95815 Office: 916.927.7223 Fax: 916.263.3341 www.calfairs.com NOTICE CALIFORNIA AUTHORITY OF RACING FAIRS BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING JOHN ALKIRE, CHAIR 12:30 P.M., TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2013 Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the California Authority of Racing Fairs’ Board of Directors will commence at 12:30 p.m., Tuesday, February 5, 2013. -

General Election - November 4, 2014 Official Certified List of Candidates 8/28/2014 Page 1 of 90 GOVERNOR

General Election - November 4, 2014 Official Certified List of Candidates 8/28/2014 Page 1 of 90 GOVERNOR EDMUND G. "JERRY" BROWN* Democratic 2355 BROADWAY #407 OAKLAND, CA 94612 (510) 628-0202 (Business) WEBSITE: www.jerrybrown.org Governor of California NEEL KASHKARI Republican 2404 P ST SACRAMENTO, CA 95816 (916) 538-6502 (Business) WEBSITE: www.neelkashkari.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Businessman LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR GAVIN NEWSOM* Democratic PO BOX 355 KENTFIELD, CA 94914-0355 (415) 346-9876 (Business) WEBSITE: www.gavinnewsom.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Lieutenant Governor RON NEHRING Republican 1015 OLD MOUNTAIN VIEW RD EL CAJON, CA 92021 WEBSITE: www.ronnehring.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Small Businessman/Educator * Incumbent General Election - November 4, 2014 Official Certified List of Candidates 8/28/2014 Page 2 of 90 SECRETARY OF STATE ALEX PADILLA Democratic 969 COLORADO BLVD STE 103 LOS ANGELES, CA 90041 (323) 254-5700 (Business) (323) 254-5788 (FAX) WEBSITE: www.alex-padilla.com E-MAIL: [email protected] California State Senator PETE PETERSON Republican 19528 VENTURA BLVD STE 507 LOS ANGELES, CA 91356 (323) 450-7536 (Business) (646) 219-5763 (FAX) WEBSITE: www.petesos.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Educator/Institute Director CONTROLLER BETTY T. YEE Democratic 381 BUSH ST STE 300 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94104 (415) 692-3556 (Business) (415) 397-3768 (FAX) WEBSITE: www.bettyyee.com E-MAIL: [email protected] California State Board of Equalization Member ASHLEY SWEARENGIN Republican 2444 MAIN ST #125 FRESNO, CA -

Sample Ballots for All Parties Are Included in This Booklet

PLEASE NOTE: The sample ballots for all parties are included in this booklet. If you plan to mark a sample ballot to bring with you to the polls, be sure to mark the ballot corresponding to your registered party preference. OFFICIAL BALLOT JUNE 7, 2016 PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY ELECTION SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTERS: To vote, fill in the oval like this: Vote both sides of the card. To vote for the candidate of your choice, fill in the OVAL next to the candidate's name. Do not vote for more than the number of candidates allowed (i.e. vote for no more than Two). To vote for a qualified write-in candidate, write in the candidate's full name on the Write-In line and fill in the OVAL next to it. To vote on a measure, fill in the OVAL next to the word "Yes" or the word "No". If you tear, deface or wrongly mark this ballot, return it to the Elections Official and get another. AMERICAN INDEPENDENT PARTY PARTY-NOMINATED OFFICES VOTER-NOMINATED AND NONPARTISAN OFFICES Only voters who disclosed a preference upon registering to vote for the same All voters, regardless of the party preference they disclosed upon registration, party as the candidate seeking the nomination of any party for the Presidency or or refusal to disclose a party preference, may vote for any candidate for a voter- election to a party committee may vote for that candidate at the primary nominated or nonpartisan office. The party preference, if any, designated by a election, unless the party has adopted a rule to permit non-party voters to vote in its primary elections. -

Recipient Amount Type Abercrombie for Governor $3,000.00 Hawaii Joe

Contributions Report Calendar Year 2012 The Walt Disney Company Political Contributions January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2012 Recipient Amount Type Abercrombie for Governor $3,000.00 Hawaii Joe Abruzzo Campaign $7,500.00 Florida Senate Katcho Achadjian for Assembly 2012 $1,000.00 CA State Janet Adkins Campaign $2,000.00 Florida House Larry Ahern Campaign $5,000.00 Florida House Richard Alarcon Officeholder Account $500.00 LA City Luis Alejo for Assembly 2012 $1,000.00 CA State Alliance for a Strong Economy $60,000.00 Florida CCE Thad Altman Campaign $2,500.00 Florida Senate Anaheim Chamber of Commerce ACCPAC $135,825.00 Anaheim Anaheim Firefighter's Association PAC $1,500.00 Anaheim Anaheim Neighborhood Association $5,000.00 Anaheim Tax Fighters for Anderson 2014 $1,000.00 CA State Antonovich Officeholder Account $500.00 LA County Brandon Arrington Campaign $6,000.00 Osecola County, Florida Carey Baker Campaign $1,000.00 Lake County, Florida Aaron Bean Campaign $3,500.00 Florida Senate LizBeth Benacquisto Campaign $2,500.00 Florida Senate Lori Berman Campaign $1,000.00 Florida House Mack Bernard Campaign $4,000.00 Florida Senate Bill Berryhill for State Senate 2012 $1,500.00 CA State Tom Berryhill for Senate 2014 $1,000.00 CA State Halsey Beshears Campaign $2,000.00 Florida House Michael Bileca Campaign $4,500.00 Florida House Marty Block for Senate 2012 $1,000.00 CA State Bob Blumenfield for Assembly 2012 $1,000.00 CA State Raul Bocanegra for Assembly 2012 $1,000.00 CA State Randolph Bracy Campaign $2,500.00 Florida House 1 Contributions