Arroyo Grande Creek Watershed Management Plan Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptual Design Documentation

Appendix A: Conceptual Design Documentation APPENDIX A Conceptual Design Documentation June 2019 A-1 APPENDIX A: CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DOCUMENTATION The environmental analyses in the NEPA and CEQA documents for the proposed improvements at Oceano County Airport (the Airport) are based on conceptual designs prepared to provide a realistic basis for assessing their environmental consequences. 1. Widen runway from 50 to 60 feet 2. Widen Taxiways A, A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4 from 20 to 25 feet 3. Relocate segmented circle and wind cone 4. Installation of taxiway edge lighting 5. Installation of hold position signage 6. Installation of a new electrical vault and connections 7. Installation of a pollution control facility (wash rack) CIVIL ENGINEERING CALCULATIONS The purpose of this conceptual design effort is to identify the amount of impervious surface, grading (cut and fill) and drainage implications of the projects identified above. The conceptual design calculations detailed in the following figures indicate that Projects 1 and 2, widening the runways and taxiways would increase the total amount of impervious surface on the Airport by 32,016 square feet, or 0.73 acres; a 6.6 percent increase in the Airport’s impervious surface area. Drainage patterns would remain the same as both the runway and taxiways would continue to sheet flow from their centerlines to the edge of pavement and then into open, grassed areas. The existing drainage system is able to accommodate the modest increase in stormwater runoff that would occur, particularly as soil conditions on the Airport are conducive to infiltration. Figure A-1 shows the locations of the seven projects incorporated in the Proposed Action. -

LOMR)? for a One-Year Premium Refund

the Arroyo Chico and Tucson Arroyo a FIRM. You may view this tutorial at: Property owners whose buildings have been watercourses. http://www.fema.gov/media- removed from an SFHA and are now located in library/assets/documents/7984 a Zone X or a Shaded Zone X may be eligible What is a Letter of Map Revision (LOMR)? for a one-year premium refund. Your lender When does a LOMR change a FIRM? must provide you with a letter agreeing to A LOMR is an official revision to the Flood remove the requirement for flood insurance. If Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) issued by the LOMRs become effective once the statutory your lender refuses to send you a letter stating Federal Emergency Management Agency Technical Appeal Period is over. The that they will not require flood insurance, you (FEMA). LOMRs reflect changes to the 100- effective date is listed on the LOMR cover will not be eligible for a refund. If you do not year floodplains or Special Flood Hazard letter. have a lender, you will not be eligible for a Areas (SFHA) shown on the FIRMs. In rare refund. To learn if you are eligible, please situations, LOMRs also modify the 500-year Can I drop my flood insurance if my follow these steps: floodplain boundaries. Changes may include residence or business is removed from ARROYO CHICO FLOODPLAIN modifications to Base Flood Elevations, the floodplain by a LOMR? 1. View the revised flood maps to REMAPPING floodplain widths, and floodways. The determine if your property has been re- QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS LOMRs are issued after a floodplain has The Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 mapped to a Zone X or Shaded Zone been remapped due to a major flood event, and the National Flood Insurance Reform Act X. -

Drainage Net

Drainage Net GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL f APER 282-A Ephemeral Streams Hydraulic Factors and Their Relation to the Drainage Net By LUNA B. LEOPOLD and JOHN P. MILLER PHYSIOGRAPHIC AND HYDRAULIC STUDIES OF RIVERS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 282-A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Fin* printing 19M Second printing 1K9 Third printing 1MB For sale by the Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey, 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Page Symbols. __________________________________________ iv Equations relating hydraulic and physiographic Abstract. __________________________________________ 1 factors....________-_______.__-____--__---_-_ 19 Introduction and acknowledgments ___________________ 1 Some relations of hydraulic and physiographic factors to Geographic setting and basic measurements ____________ 2 the longitudinal profile.___________________________ 24 Measurement of hydraulic variables in ephemeral streams, 4 Channel roughness and particle size.______________ 24 General features of flow _________________________ 4 Effect of change of particle size and velocity on Problems of measurement._______________________ 6 stream gradient.____.__._____-_______-____--__ 26 Changes of width, depth, velocity, and load at indi Equilibrium in ephemeral streams _____________________ 28 vidual channel cross sections ___________________ 7 Mutual adjustment of hydraulic factors._____.._._ -

Floods Floods Are the Most Common Natural Disasters in the Country

Floods Floods are the most common natural disasters in the country. However, not all floods are alike. Some can develop slowly over a long period of rain or during warm weather after a heavy snowfall. Others, such as flash floods, can happen quickly, even without any visible signs of rain. It is important to be prepared for flooding no matter where you live, but especially if you live in a low-lying area, near water or downstream from a dam. Even a very small stream or a dry creek bed can overflow and cause flooding. Prepare supplies Make a Plan Stay informed Prepare an emergency supply kit, Develop a family emergency plan. Know the terms which includes items like non- Your family may not be together in the perishable food, water, battery same place when disaster strikes, so Flash Flood Warning: there has been a sudden flood. Head for operated or crank radio, extra it is important to know how you will flashlights and batteries. Consider contact one another, how to get back higher ground immediately keeping a laptop computer in your together and what you will do in case height. vehicle. The kit should include: of emergency. Flood Warning: there has been Prescriptions Plan places where your family will a flood or will there be a flood Bottled water, a battery radio meet, both within and outside your soon. It is advised to evacuate and extra batteries, a first aid immediate neighborhood. immediately. kit and a flashlight. Copies of important Be sure to take into account the Flood Watch: It is possible that specific needs of family members. -

Sediment Discharge in the Upper Arroyo Grande and Santa Rita Creek Basins 23 5

PB 256 422 Sediment Discharge in the Upper Arroyo Grande and 41,111 anta Rita Creek Basins, tot,:San Luis Obispo County, 1144300,6k California U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVPFY Water-Resources Investigations 151/4 76-64 101„,14.11kup lemw QE Prepared in cooperation with the 75 .U58w SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY no.76-64 1976 ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT lkigtikPHIC DATA I. ReportuNo.Gs 2. 3. Recipient's Accession No. S NRD/WRI-76/053 4. Title and Subtitle 5.keport Date WS14/3610WPOISCHARGE IN THE UPPER ARROYO GRANDE AND SANTA RITA June 1976,/ 6. ben,/ erctFardthf INS, SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA (t;"f„ ,, ,/,,,,,,,, °./. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Rept. .„ J. M. Knott,! N'- USGS/WRI 76-64 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Project/Task/Work Unit No. U.SAeological Survey, Water Resources Division California District )- 11. Contract/Grant No. 345 Middlefield Road Menlo Park, California 94025 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report & Period U.S. Geological Survey, Water Resources Division Covered California District Final 345 Middlefield Road 14. Menlo Park, California 9409c 15. Supplementary Notes Prepared in cooperation wit igir. .ng Department 16.AbstractsSediment data collected in the upper Arroyo Grande and Santa Rita Creek basins during the 1968-73 water years were analyzed to determine total sediment discharge at four stations in the basins. Water discharge and total sediment discharge at these stations, representative of the 1943-72 period, were estimated from'long-term flow data for nearby gaging stations and water-sediment discharge relations determined for the 1968-73 water years. -

The Central Arroyo Stream Restoration Program

This presentation premiered at WaterSmart Innovations watersmartinnovations.com Breaking Down the Barriers to Generate Sustainable Water Solutions The Arroyo Seco – A Case Study Tim Brick and Eliza Jane Whitman Arroyo Seco Foundation The Arroyo Seco Major tributary of the Los Angeles River Linking downtown LA to the San Gabriel Mountains Home of JPL and the Rose Bowl Watershed Management Program for last ten years Corps Feasibility Study The Historic Arroyo Seco Two different views of the Colorado Street Bridge The Most Celebrated Canyon in Southern California “This arroyo would make one of the greatest parks in the world” - Theodore Roosevelt, 1911 Current Status of the Arroyo Seco Though long celebrated as one of the most beautiful streams in Southern California, the Arroyo Seco has not escaped wide-spread damage caused by human impact Damage Caused by Urbanization / Channelization * destruction of habitat and wildlife * reduced infiltration * impaired water quality Central Arroyo Planning How does a golf course fit into watershed management and restoration? Alternative Alignments for Stream Restoration Celebrating the Arroyo The Central Arroyo Stream Restoration Program Improving the health of a stream and ensuring the future and sustainability of Pasadena The Central Arroyo Brookside Golf Course Project Accomplishments Improved water quality Enhanced trail network Implemented runoff BMPs Restored aquatic habitat Reintroduced the native Arroyo Chub Provided a model of stream restoration for urban SoCal Improved Aquatic Habitat ☼ Created backwater pools and structures to provide resting, foraging, and spawning areas for fish. ☼ Stabilized stream banks ☼ Improvements were constructed with natural materials (native trees and arroyo Backwater pool and stone). woody debris ☼ Under direction of CDFG, reintroduced 300 arroyo chub to the central Arroyo Seco. -

San Luis Obispo County, California and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 2 SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ARROYO GRANDE, CITY OF 060305 ATASCADERO, CITY OF 060700 EL PASO DE ROBLES, CITY OF 060308 GROVER BEACH, CITY OF 060306 MORRO BAY, CITY OF 060307 PISMO BEACH, CITY OF 060309 SAN LUIS OBISPO, CITY OF 060310 SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY 060304 (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) REVISED: November 16, 2012 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 06079CV001B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this FIS may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: August 28, 2008 Revised Countywide FIS Date: November 16, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS – Volume 1 Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of Study 1 1.2 Authority and Acknowledgments 1 1.3 Coordination 4 2.0 AREA STUDIED 5 2.1 Scope of Study 5 2.2 Community Description 6 2.3 Principal Flood Problems -

Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes National Wildlife Refuge Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Complex 2493 Portola Road, Suite A Ventura, CA 93003 http://www.fws.gov/refuge/guadalupe-nipomo_dunes/ Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes California Telecommunications Relay Service Voice/TTY: 711 National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish & Willdife Service 1 800/344-WILD http://www.fws.gov Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan August 2016 and Environmental Assessment August 2016 Photo: Ian Shive Vision Statement Propelled by relentless ocean waves and strong onshore winds, small grains of sand scour and accumulate to form the impressive migrating dunes of the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes National Wildlife Refuge (Refuge). Harsh, but dynamic processes create unique habitats among the dunes for imperiled plants and animals such as La Graciosa thistle, marsh sandwort, California red- legged frog, and western snowy plover. The Refuge lies within the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Complex (Dunes Complex), an 18-mile- long stretch of coastal dunes located north of Point Sal and south of Pismo Beach. To conserve the dynamic landscape and imperiled natural resources of the Refuge and the Dunes Complex, the Service works cooperatively with other agencies, non-profit organizations, local businesses, private landowners, and private citizens. Working together, we instill stewardship through activities that include habitat restoration, protection of cultural resources, recovery of threatened and endangered species, and opportunities for high-quality visitor experiences in this unique and spectacular dunes landscape. Such cooperative efforts enable all partners to share limited resources to meet common goals, thereby achieving much more together than we could alone. -

Hydrology and Water Quality

Environmental Impact Analysis – Hydrology and Water Quality 4.8 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY This section identifies potential impacts to drainage and watershed resources that would result from the proposed project. A watershed is a region, usually defined by ridgelines, which drains into a specified body of water. Watershed-related impacts are those associated with grading and drainage, erosion and water quality that may arise as a result of construction and occupancy of facilities. The Port Master Plan Final Program EIR (2004) and Hydrology Report (Sherwood Design Engineers [Sherwood] 2014) are incorporated by reference into the analysis below. The Final Program EIR is available for review at the Harbor District office and the Hydrology Report is located in Appendix F of this EIR. 4.8.1 Existing Conditions 4.8.1.1 Regional Drainage Pattern The primary surface drainage feature affecting San Luis Bay and the Avila Beach area is San Luis Obispo Creek, which drains areas north of the City of San Luis Obispo. The San Luis Obispo Creek estuary is located about two miles west of the Harbor Terrace planning area. Historically, flow within much of San Luis Obispo Creek has been absent primarily during the late summer months (July through October) of low rainfall years. High flows within the creek occur primarily during and immediately following significant storm events. The City of San Luis Obispo constructed a Wastewater Reclamation Facility in the 1940s near the southern city boundary, and began direct discharge to the creek in the late 1960s. This 5.0 to 5.5 cubic feet per second (cfs) supplemental discharge flow has altered natural stream flow of San Luis Obispo Creek resulting in a perennial stream. -

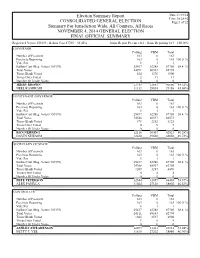

Gems Election Summary Report

Election Summary Report Date:11/19/14 Time:10:28:42 CONSOLIDATED GENERAL ELECTION Page:1 of 22 Summary For Jurisdiction Wide, All Counters, All Races NOVEMBER 4, 2014 GENERAL ELECTION FINAL OFFICIAL SUMMARY Registered Voters 150139 - Ballots Cast 87705 58.42% Num. Report Precinct 163 - Num. Reporting 163 100.00% GOVERNOR Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. Voters 150139) 25417 62288 87705 58.4 % Total Votes 24891 60901 85792 Times Blank Voted 524 1376 1900 Times Over Voted 2 11 13 Number Of Under Votes 0 0 0 JERRY BROWN 13759 32847 46606 54.32% NEEL KASHKARI 11132 28054 39186 45.68% LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. Voters 150139) 25417 62288 87705 58.4 % Total Votes 24546 60027 84573 Times Blank Voted 871 2252 3123 Times Over Voted 0 9 9 Number Of Under Votes 0 0 0 RON NEHRING 12116 30407 42523 50.28% GAVIN NEWSOM 12430 29620 42050 49.72% SECRETARY OF STATE Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. Voters 150139) 25417 62288 87705 58.4 % Total Votes 24208 58997 83205 Times Blank Voted 1209 3287 4496 Times Over Voted 0 4 4 Number Of Under Votes 0 0 0 PETE PETERSON 12544 31859 44403 53.37% ALEX PADILLA 11664 27138 38802 46.63% CONTROLLER Polling VBM Total Number of Precincts 163 0 163 Precincts Reporting 163 0 163 100.0 % Vote For 1 1 1 Ballots Cast (Reg. -

Sample Ballot Continued…

WHAT’S NEW FOR THIS ELECTION Top Two Primary What is it? In 2010, California voters approved Proposition 14 creating the “Top- Two Primary,” which replaced the traditional party-nominated primary. Under the Top-Two Primary laws, all candidates running, regardless of their party preference, appear on a single combined ballot, and voters can vote for any candidate from any political party. The candidates who receive the highest and second-highest number of votes cast at the Primary election advance to the General election. This change applies to federal and state contests, except for President. The rules for non-partisan contests (i.e. counties, cities, school and special districts) did not change. For the Presidential Primary, Party Ballots Still Exist Since the Top Two Primary rules do not affect the election of party nominee for President, party-specific ballots will be issued for this Presidential Primary Election. Only voters who are registered to vote with a specific party are allowed to vote in that party’s Presidential nominee contest. All Other Contests Are Open to All Voters The new rules apply to U.S. Senate, U.S. Congressional, statewide and state legislative offices. Candidates for these offices are no longer nominated by party. As a result, voters can vote for any candidate on the ballot regardless of the candidate’s party preference. These contests are now referred to as “voter-nominated offices.” Again, in these contests, only the two candidates who receive the highest and second-highest vote totals will be on the ballot in the November General Election. Party Preference and Political Party Endorsement The term "party preference" is now used in place of the term "party affiliation”. -

YES on Proposition 51

YES on Proposition 51 (As of 8/4/16) Organizations California Association of School Business Officials California County Superintendents Educational Services Association California Democratic Party California Nevada Cement Association California Housing Consortium California Republican Party California Retired Teachers Association California School Boards Association California School Nurses Organization California State Firefighters’ Association California State PTA California Taxpayers Association California Young Democrats Central Valley Education Coalition Community College League of California Construction Management Association of America, Southern California Chapter Contractors Association of Truckee Tahoe County School Facilities Consortium Democratic Party of the San Fernando Valley Faculty Association of California Community Colleges League of Women Voters of California Los Angeles County Democratic Party National Electrical Contractors Association, Northern California Chapter Rural Community Assistance Corporation School Energy Coalition School Services of California, Inc. Small School Districts’ Association Statewide Educational Wrap Up Program Western Manufactured Housing Communities Association American Council of Engineering Companies, California American Institute of Architects, California Council Associated General Contractors of California Association of California Construction Managers California Apartment Association Statewide Leaders and Elected Officials Gavin Newsom, Lieutenant Governor of California Tom Torlakson,