A Time Half Dead at the Top: the Professional Societies and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mergers in Public Higher Education in Massachusetts. Donald L

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 Mergers in public higher education in Massachusetts. Donald L. Zekan University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Zekan, Donald L., "Mergers in public higher education in Massachusetts." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 5062. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/5062 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIVE COLLEGE DEPOSITORY MEaRGERS IN PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATIOJ IN MASSACHUSEHTS A Dissertation Presented DCmLD L. ZERAN Subonitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DCXnOR OF EDUCATIOI MAY 1990 School of Education Cc^^ight Donald Loiiis Zekan 1990 All Rights Reserved MERGERS IN PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATIC^J IN MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation Presented by DCmiiD L. ZEKAN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Hiis dissertation was canpleted only with the support and encouragement of many distinguished individuals. Dr. Robert Wellman chaired the committee with steady giiidance, numerous suggestions and insights, and constant encouragement. Dr. Franklin Patterson's observations and suggestions were invaluable in establishing the scope of the work and his positive demeanor helped sustain me through the project. Dr. George Siilzner's critical perspective helped to maintain the focus of the paper through the myriad of details uncovered in the research. At Massasoit Community College, the support and understanding of President Gerard Burke and the Board of Trustees was essential and very much appreciated. -

Umass Selects a New President: Elements of a Search Strategy Richard A

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 8 | Issue 2 Article 3 9-23-1992 UMass Selects a New President: Elements of a Search Strategy Richard A. Hogarty University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Education Policy Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Hogarty, Richard A. (1992) "UMass Selects a New President: Elements of a Search Strategy," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 8: Iss. 2, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol8/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMass Selects a Elements of a New President Search Strategy Richard A. Hogarty The selection of a new university president, an event of major importance in academic life, is usually filled with tensions on the part of those concerned about its outcome. The 1992 presidential search at the University of Massachusetts exemplifies such ten- sions. There were mixed reactions to the overall performance. When they finished reviewing candidates, the search committee had eliminated all but Michael K. Hooker, who, they deemed, has the necessary competence, vision, and stature for the task. The main conflict centered on the question of "process" versus "product. " The trustees rejoiced in what they considered an impressive choice, while many faculty were angered over what they considered a terrible process. -

To All 18F Students!

HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE Orientation 2018 STUDENT PROGRAM SCHEDULE (At Hampshire) broad knowledge will not come predigested...it will come as a natural consequence of exploration. From The Making of a College, by Franklin Patterson and Charles Longsworth, 1965 Disoriented? Uncertain? Lost? If at any time during orientation you are lost, uncertain of where you should be, or wondering where your orientation group is meeting, or if you have any questions, please visit our ORIENTATION HELP DESK. The help desk is located in the lobby of Franklin Patterson Hall and is staffed from Friday, August 31, through Monday, September 3, from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Follow all the great things happening at orientation on our social media! @NewToHamp /NewToHamp Show off your orientation experience using these hashtags: #NewToHamp | #HampOrientation Illustrations by Celeste Jacobs 14F Orientation 2018 Welcome TO ALL 18F STUDENTS! WE’RE GLAD YOU’RE HERE! Your journey at Hampshire begins with orientation, a time for you to learn about the College, meet new people, and settle in. The program you are about to take part in is designed to give you a sense of daily life on campus. Through performances, presentations, and a variety of activities, you will start to experience what it means to be a part of the Hampshire community. Orientation leaders are some of your best resources on campus. They chose to be leaders because they want to help you as you begin to establish yourself at Hampshire — take advantage of that! Remember, they’re here for you. As you participate in this weekend’s activities, there may be times when you feel overwhelmed or uncertain. -

1977-1978 Officefice of Institutional Researesearch F U N Iv Ers Itv O F M a S Sa C H U Se T Ts A...T a Rn He Rs T

Factbook University of Massachusetts Amherst 1977-1978 Officefice of Institutional ResearchResea www.umass.edu/oirw.umass.edu F_u_n_iv_ers_itv_o_f_M_a_s_sa_C_h_u_se_t_ts_a...t A_rn_he_rs_t_-... _ • • • Preface • This factbook has been compiled as a continued effort • (revived last year) to meet the many needs for a compendium of statistical information about the campus. The FACTBOOK • will allow its reade~s to have at hand in one volume the most current data available on most campus operations, as .' well as some historical data reaching as far back as 1863, the first year of operation of what is now the Amherst Campus of the University of Massachusetts. • I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge Melissa Sherman" who typed theinany revisions_of this report, • and thank her for her valuable assistance and patience. • • /A. , ,IfII 7JlIA /I" c; . , • Alison A. Cox ' , Assistant for Institutional Studies .' January 1978 • About the Cover: Photographs i 11 us tra te the Amhers t Campus in four different sta of development. They are, clockwise from • upper left c. 1950, c. 1932, c. 1890, c. 1975. .' • - ; FFICEOFBUDGETINGAND INSTITUTIONAL STUDIES, WHITMORE ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, AMHERST, MASSACHUSETIS01002 (413) 545-2141 I UNIVERSITY or MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST I 1977-1978 FACTBOOK I Co tents I. HISTORY I THE TOWN OF AMHERST. 2 I, HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE UNIVERSITY. 3 ESTABLISHMENT OF SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES. 5 PAST PRESIDENTS AND CHANCELLO.RS. 6 I FIVE COLLEGE COOPERATION . 7 COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE. 9 I SUMMARY INFORMATION SHEET. 10 II. ORGANIZATION I CAMPUS ORGANIZATION AND ADMINISTRATION. 12 ORGANIZATIONAL CHART. 13 DESCRIPTION OF ORGANIZATIONAL UNITS. 14 • BoARD OF TRUSTEES. '. ; . 22 II ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS. -

Searching for a Umass President: Transitions and Leaderships, 1970-1991 Richard A

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 7 | Issue 2 Article 3 9-23-1991 Searching for a UMass President: Transitions and Leaderships, 1970-1991 Richard A. Hogarty University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Education Policy Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Hogarty, Richard A. (1991) "Searching for a UMass President: Transitions and Leaderships, 1970-1991," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 7: Iss. 2, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Searching for a Transitions and UMass President Leaderships, 1970-1991 Richard A. Hogarty This article traces the history of the five presidential successions that have taken place at the University of Massachusetts since 1970. No manual or campus report will reveal the one best way to conduct a presidential search. How to do so is not easy to prescribe. Suitably fleshed out, the events surrounding these five searches tell us a great deal about what works and what doesn 't. It is one thing to offer case illustrations ofpast events, another to say how they might be put to use by other people in another era with quite different situations and concerns. In evaluating these transitions and leaderships, this article also raises the question of what is the proper role of the president in university governance. -

Umass Events and Announcements

Stonewall Center UMass Events and Announcements Last Day to Submit to the LGBTQIA+ Art Show To mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in June 2019, the UMass Stonewall Center is curating an art exhibit -- “LGBTQIA+ Identity, Community, and Activism Today” -- for March 18-23 in the UMass Student Union Art Gallery, which is temporarily located in 310 Bartlett Hall. Submissions in all art mediums are welcomed, including painting, photography, sculpture, film and projected media, and performance. Submissions are open to all and the work does not need to be explicitly LGBTQIA+. To submit a work or to sign up to perform, please fill out the form here. The opening visual arts reception/performance night is March 19 from 6-9 p.m. Art show Facebook page. The deadline for submissions is March 1. Rec Center LGBTQIA+ WorkOUT Group The Stonewall Center is organizing an LGBTQIA+ and allies workout group to meet at the Rec Center as often as the group desires. If interested in being part of this group, please email Stonewall. 10th Annual Five College Queer Gender & Sexuality Conference March 1-3, Franklin Patterson Hall, Hampshire College Among the many conference events are: -- a talk by Gavin Grimm, whose anti-trans discrimination case appeared before the Supreme Court -- a screening of the 2016 movie Kiki with a discussion led by cast member Chi Chi Mizrahi -- a keynote with Caleb Luna and Cyree Jarelle Johnson on femme modalities, disability justice, and fat liberation -- a performance by Grammy-nominated singer and poet Mary Lambert -- plus a QTPOC dessert reception, a queer Shabbat, and a drag brunch file:///H|/email.htm[3/1/2019 10:21:02 AM] "Threshold Academy: Why You Should Drop Out of School and Become a Utopian Bookseller" -- a talk by Zoe Tuck Friday, March 1, 2:30 p.m., W465 South College Sponsored by the graduate student Trans Studies Working Group. -

Bradbury Seasholes

Bradbury Seasholes Bradbury Seasholes served Tufts University and the Department of Political Science with distinction for thirty-two years. Through his teaching, scholarship, administrative positions and counseling of thousands of students, Seasholes displayed a record of extraordinary achievement. Seasholes was born and raised in Ohio and received his undergraduate education at Oberlin College. At Oberlin Seasholes pursued a doctorate in his major, Political Science at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. At Chapel Hill, Seasholes sailed through his courses, orals, and dissertation with honors and gained his first teaching experience as well. His dissertation dealt with “Negro,” now “Black” and/or “African-American,” political participation; an area to which he later made significant contributions. At Chapel Hill he met visiting Professor Robert Wood from MIT who enticed Seasholes to Cambridge, Massachusetts and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Political Science Faculty. With is new Ph.D. he worked with Wood at The Institute and the Harvard-MIT Joint Center for Urban Studies on research and scholarly papers. In 1962, at the annual Tufts Assembly on Massachusetts Government, Seasholes met Professor Robert Robbins, Chair of the Department of Political Science, and Lincoln Filene Center Director, Franklin Patterson. These two professors, impressed with the Seasholes-Wood paper and Seasholes’ solid Political Science credentials made Seasholes an offer to come to Tufts University. Thus, Seasholes came to Tufts in July, 1963 as Assistant Professor of Political Science and Director of Political Science for the Lincoln Filene Center. He worked with considerable energy and dedication in many kinds of academic and real-world enterprises. -

Integrating Primary Care and Biomedical Research

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS History of UMass Worcester Office of Medical History and Archives 2012 The University of Massachusetts Medical School, A History: Integrating Primary Care and Biomedical Research Ellen S. More University of Massachusetts Medical School Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/umms_history Part of the Health and Medical Administration Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Repository Citation More ES. (2012). The University of Massachusetts Medical School, A History: Integrating Primary Care and Biomedical Research. History of UMass Worcester. https://doi.org/10.13028/e2m6-hs02. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/umms_history/1 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of UMass Worcester by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Massachusetts Medical School, A History: Integrating Primary Care and Biomedical Research Ellen S. More The Lamar Soutter Library University of Massachusetts Medical School The University of Massachusetts Medical School, A History: Integrating Primary Care and Biomedical Research Ellen S. More Lamar Soutter Library University of Massachusetts Medical School 2012 http://escholarship.umassmed.edu/umms_history/1/ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….......... 1 Part 1 (1962-1970) Chapter 1—Does Massachusetts Really Need Another Medical School?........ -

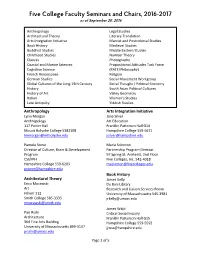

Five College Faculty Seminars and Chairs, 2016-17

Five College Faculty Seminars and Chairs, 2016-2017 as of September 20, 2016 Anthropology Legal Studies Architectural Theory Literary Translation Arts Integration Initiative Marxist and Postcolonial Studies Book History Medieval Studies Buddhist Studies Middle Eastern Studies Childhood Studies Number Theory Classics Photography Coastal and Marine Sciences Propositional Attitudes Task Force Cognitive Science (PATF/Philosophy) French Renaissance Religion German Studies Social Movement Workgroup Global Cultures of the Long 19th Century Social Thought / Political Economy History South Asian Political Cultures History of Art Valley Geometry Italian Women's Studies Late Antiquity Yiddish Studies Anthropology Arts Integration Initiative Lynn Morgan Jana Silver Anthropology Art Education 117 Porter Hall Franklin Patterson Hall G14 Mount Holyoke College 5382108 Hampshire College 559-5671 [email protected] [email protected] Pamela Stone Marla Solomon Director of Culture, Brain & Development Partnership Program Director Program 97 Spring St. Amherst, 2nd Floor CSI/FPH Five Colleges, Inc. 542-4018 Hampshire College 559-6203 [email protected] [email protected] Book History Architectural Theory James Kelly Erica Morawski Du Bois Library Art Research and Liaison Services Room Hillyer 112 University of Massachusetts 545-3981 Smith College 585-3335 [email protected] [email protected] James Wald Pari Riahi Critical Social Inquiry Architecture Franklin Patterson Hall G15 364 Fine Arts Building Hampshire College 559-5592 University -

Hampshire College Spiritual Life; Mount Holyoke College Religious and Spiritual Life; and Smith College Religious and Spiritual Life

Sr. Helen Prejean , Anti-Death Penalty Advocate Anti-death penalty advocate Sr. Helen Prejean, C.S.J. comes to the Connecticut River Valley on Thursday, September 20, 2012. A pre-lecture screening of the film based on her book “Dead Man Walking” will be screened at 8 pm. on Friday, September 14 in East Lecture Hall in Franklin Patterson Hall, Hampshire College. The screening is free and open to the public. Sister Helen will hold a conversation with invited guests at Amherst College before going to Hampshire College to offer the September 20 lecture at 8 pm. in the Main Lecture Hall of Franklin Patterson Hall. A book signing will follow in the faculty lounge of the same building. Both the lecture and the book signing are free and open to the public. Sister Helen Prejean, C.S.J is a pioneering opponent of the death penalty, helping to shape the Catholic Church’s opposition to state executions. She is the author of “Dead Man Walking”, an account of her relationship with death row inmate Patrick Sonnier. “Dead Man Walking” became an Academy Award- winning movie, an opera, and a play. Since 1984, Prejean has divided her time between educating citizens about the death penalty and counseling individual death row prisoners. She has accompanied six men to their deaths. In addition to Dead Man Walking, she also authored “The Death of Innocents: An Eyewitness Account of Wrongful Executions”, released by Random House in December of 2004. Prejean’s current book is “River of Fire: My Spiritual Journey”. For more information, please contact [email protected] or phone 413.559.5282. -

Bulletin University Publications and Campus Newsletters

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston 1971-1977, UMass Boston Bulletin University Publications and Campus Newsletters 9-17-1974 Bulletin - Vol. 09, No. 03 - September 17, 1974 University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/umb_bulletin Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons Recommended Citation University of Massachusetts Boston, "Bulletin - Vol. 09, No. 03 - September 17, 1974" (1974). 1971-1977, UMass Boston Bulletin. Paper 170. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/umb_bulletin/170 This University Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications and Campus Newsletters at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1971-1977, UMass Boston Bulletin by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I I I I I I I I I r-t I University of Massachusetts at Boston u _Volume 9, Number 3 September 17, 1974 Faculty Meeting Professor Paul Gagnon (History I I) was elected by faculty members to serve as the UMass-Boston faculty representative to the Board of Trustees of the University of Massachusetts at the first faculty convocation of the academic year. On a motion introduced by Professor James Broderick (English I) the fac ulty attending the meeting voted unanimously to instruct Professor Gagnon to inform the President of the University and the Board of Trustees of the faculty's "surprise and dismay" with the Board's vote in June on the Polley Statement and Poli~y Guideline for the future enrollment and composition of the Harbor Campus. -

IV Community, Justice, and Resilience

dIV HAMPSHIRE IN ACTION Community, Justice, and Resilience June 1–3, 2018 2 ONGOING ALL-WEEKEND ACTIVITIES HAMPSTORE Harold F. Johnson Library, ground floor Friday: 1–5 P.M. Visit the newly renovated Hampstore and pick up your College gear. KERN KAFÉ Friday: 10 A.M.–3 P.M. Saturday: 10 A.M.–2:30 P.M. R.W. Kern Center, first floor Stop by and pick up some of our delicious pastries. Thirsty? We’ve got an espresso, a latte, or a daily-drip brew (hot or cold) just for you. THE MUSEUM OF THE OLD COLONY (EXHIBITION) Friday: 10 A.M.–7 P.M. Saturday: 10 A.M.–4 P.M. Sunday: 10 A.M.–2 P.M. Harold F. Johnson Library, Hampshire College Art Gallery The Museum of the Old Colony, a conceptual art installation by Hartford-based artist Pablo Delano, employs enlarged and carefully-sequenced reproductions of original historical materials to reveal and reflect on the faultlines of US-Puerto Rico relations. The exhibition is co-curated by the artist and Gallery Director Amy Halliday, with assistance from Professor Wilson Valentín-Escobar, Joy Diaz 18S and Charlotte Hawkins 13F. VIEW THE SOURCE WALL OF RESILIENCE Franklin Patterson Hall, exterior Created as a Div III project by Mika Gonzalez 13F, this mural reflects the power, connectivity, and divinity of femmes and trans femmes of color in the fight for Black and Brown liberation. The medium was chosen for its ability to express political realities through collective imagination. From the conception of the project, the artist recognized the importance of working collaboratively and valuing the voices of many, and the mural was imagined and co-created by members of Hampshire College SOURCE (Students of Under-Represented Cultures and Ethnicities).