EJC Cover Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASSENET and HIS OPERAS Producing at the Average Rate of One Every Two Years

M A S S E N E T AN D HIS O PE RAS l /O BY HENRY FIN T. CK AU THO R O F ” ” Gr ie and His Al y sia W a ner and H W g , g is or ks , ” S uccess in Music and it W How is on , E ta , E tc. NEW YO RK : JO HN LANE CO MPANY MCMX LO NDO N : O HN L NE THE BO DLEY HE D J A , A K N .Y . O MP NY N E W Y O R , , P U B L I S HE R S P R I NTI N G C A , AR LEE IB R H O LD 8 . L RA Y BRIGHAM YO UNG UNlVERS lTW AH PRO VO . UT TO MY W I FE CO NTENTS I MASSENET IN AMER . ICA. H . B O GRAP KET H II I IC S C . P arents and Chi dhoo . At the Conservatoire l d . Ha D a n R m M rri ppy ys 1 o e . a age and Return to r H P a is . C oncert a Successes . In ar Time ll W . A n D - Se sational Sacred rama. M ore Semi religious m W or s . P ro e or and Me r of n i u k f ss be I st t te . P E R NAL R D III SO T AITS AN O P INIO NS . A P en P ic ure er en ne t by Servi es . S sitive ss to Griti m h cis . -

De Senectute Cantorum

DE SENECTUTE CANTORUM By CARL VAN VECHTEN Downloaded from "T" AM not sure," writes Arthur Symons in his admirable essay I on Sarah Bernhardt, "that the best moment to study an artist is not the moment of what is called decadence. The first energy of inspiration is gone; what remains is the method, the mechanism, and it is that which alone one can study, as one http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ can study the mechanism of the body, not the principle of life itself. What is done mechanically, after the heat of the blood has cooled, and the divine accidents have ceased to happen, is precisely all that was consciously skillful in the performance of an art. To see all this mechanism left bare, as the form of a skeleton is left bare when age thins the flesh upon it, is to learn more easily all that is to be learnt of structure, the art which not art but nature has hitherto concealed with its merciful at University of Birmingham on March 21, 2015 covering." Mr. Symons, of course, had an actress in mind, but his argument can be applied to singers as well, although it is safest to remember that much of the true beauty of the human voice inevitably departs with the youth of its owner. Still, style in singing is not noticeably affected by age and an artist who possesses or who has acquired this quality very often can afford to make lewd gestures at Father Time. If good singing depended upon a full and sensuous tone such artists as Ronconi, Victor Maurel, Max Heinrich, Ludwig Wtillner, and Maurice Renaud would never have had any careers at all. -

View Catalogue

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA [email protected] • www.lubranomusic.com Telephone 516-922-2192 Catalogue 88 SUMMER POTPOURRI 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com Telephone 516-922-2192 1 CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). Please note that all material is in good antiquarian condition unless otherwise described. All items are offered subject to prior sale. We thus suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper right of our homepage. We ask that you kindly wait to receive our invoice to ensure availability before remitting payment. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. New York State sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. We accept payment by: - Credit card (VISA, Mastercard, American Express) - PayPal to [email protected] - Checks in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank - International money order - Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) - Automated Clearing House (ACH), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. -

New York As the Operatic Metropolis by Henry T

NEW YORK AS THE OPERATIC METROPOLIS BY HENRY T. FINCK HETHER New York really is the rar and Caruso in the same opera, because W operatic center of the universe, as the fame of either alone fills the house. some critics and observers claim, is a ques Grau used to delight in arranging all-star tion worth considering. Doubtless the casts that took one's breath away. Once, Metropolitan has a larger number of great when he gave "Les Huguenots" with singers than any foreign opera-house; but Sembrich, Nordica, Jean and Edouard de it is also true that there have been years Reszke, besides Maurel, and Plangon, he when the number of first-class artists asked two dollars extra for parquet seats; gathered under its roof was greater than but often he provided casts nearly or quite it is now. This is particularly the case as remarkable without raising the prices. with the lowest voices. Among fourteen We recall, for instance, "Carmen," with mezzo-sopranos and contraltos, Louise Calve, Fames, Jean and Edouard de Homer alone upholds the high standards Reszke; "Tristan und Isolde" with Lilli of the past; and while Allen Hinckley, Lehmann (or Nordica), Schumann- Andrea de Segurola, and Herbert Wither- Heink, Jean and Edouard de Reszke, and spoon are good bas^s, they do not'rank Bispham (or Van Rooy). These cannot with Edouard de Reszke, Emil Fischer, be equaled to-day. Nevertheless, some of and Pol Plangon. Among the baritones, the present Metropolitan casts are not at however, there are no fewer than seven all to be sneered at. -

The Music Trade Review

Music Trade Review -- © mbsi.org, arcade-museum.com -- digitized with support from namm.org THE MUSIC TRADE REVIEW GEISI, OTTOBONI, SANGIOKGI AND SALA, WITH OKCH. TENOR SOLO IN ITALIAN, ORCH. ACCOMP. LATEST RECORD LISTS. 10572 Luisa Miller, Quando le sere al placido 61170 Ernani—Act. 1. No. 9—Finale Verdi 10 (Verdi)^Record made in Milan LA SCALA CHORUS., WITH ORCII. Romeo Berti Victor Co.'s and Columbia Phonograph Co.'s 01171 Ernani—Act 2. No. 10—Esultiam (Day of 10 SOPRANO AND BARITONE DUET IN ITALIAN, ORCH. ACCOMP. Lists for March—Edison List Was Printed Gladness) Verdi 30050 Serenata (Schubert) BERNACCHI, COLAZZA AND DE LUNA, WITH ORCH. ...Mine. Gina Ciaparelli and Taurino Parvis Last Week in This Department. 61172 Ernani—Act 2. No. 11—Oro quant' oro 10 TENOR SOLO, ORCII. ACCOMP. (1 am the Bandit Ernani!) Verdi 30051 I'll Sing Thee Songs of Araby (Clay) CARONNA AND DE LUNA, WITH ORCH. Henry Burr NEW VICTOR RECORDS. 30052 G. A. It. Patrol (R. Fassett) 01173 Ernani—Act 2. No. 12—La vedremo, o Prince's Military Band veglio audace (I Will Prove, Audacious 10 30053 Patrol of the Scouts (E. Boccalari) No. ARTHUH PKYOR S BAM). Size. Greybeard) Verdi 5005 Blue Jackets March Bennet 10 GRISI, CIGADA, OTTOBONI AND LA SCALA CHORUS, Prince's Military Band 31609 La Lettre de Manon Gillet 12 WITH ORCH. BARITONE AND TENOR DUET, ORCH. ACCOMP. SOUSA'S BAND. 61174 Ernani—Act 2. No. 13—Vieni meco (Come 10 30054 In a Chimney Corner (On a winter's night) Thou Dearest Maiden) Verdi (Harry Von Tilzer) Collins and Harlan 4981 The Preacher and the Bear Sorensen 10 VAUDEVILLE SPECIALTY, OUCH. -

Irving Ritterman Collection of Autographs and Musical Memorabilia

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9m3nd0xq No online items Finding Aid for the Irving Ritterman Collection of Autographs and Musical Memorabilia 1901-1961 Processed by Performing Arts Special Collections staff. UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm ©2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 112-M 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Irving Ritterman Collection of Autographs and Musical Memorabilia, Date (inclusive): 1901-1961 Collection number: 112-M Creator: Ritterman, Irving Extent: 2 boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: The majority of the collection consists of autographs and autographed photographs of famous composers, conductors, and vocalists from the early 20th century. Language of Material: Collection materials in English Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

THE RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE Given Below Is the Featured Artist(S) of Each Issue (D=Discography, B=Biographical Information)

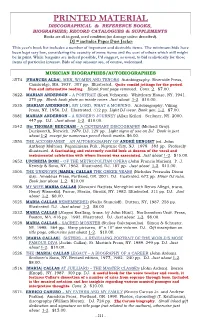

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, BIOGRAPHIES; RECORD CATALOGUES & SUPPLEMENTS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket This year’s book list includes a number of important and desirable items. The minimum bids have been kept very low, considering the scarcity of some items and the cost of others which still might be in print. While bargains are indeed possible, I’d suggest, as usual, to bid realistically for those items of particular interest. Bids of any amount are, of course, welcomed. MUSICIAN BIOGRAPHIES/AUTOBIOGRAPHIES 3574. [FRANCES ALDA]. MEN, WOMEN AND TENORS. Autobiography. Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA. 1937. 307 pp. Illustrated. Quite candid jottings for the period. Fun and informative reading. Blank front page removed. Cons. 2. $7.00. 3622. MARIAN ANDERSON – A PORTRAIT (Kosti Vehanen). Whittlesey House, NY. 1941. 270 pp. Blank book plate on inside cover. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3535. [MARIAN ANDERSON]. MY LORD, WHAT A MORNING. Autobiography. Viking Press, NY. 1956. DJ. Illustrated. 312 pp. Light DJ wear. Book gen. 1-2. $7.00. 3581. MARIAN ANDERSON – A SINGER’S JOURNEY (Allan Keiler). Scribner, NY. 2000. 447 pp. DJ. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3542. [Sir THOMAS] BEECHAM – A CENTENARY DISCOGRAPHY (Michael Gray). Duckworth, Norwich. 1979. DJ. 129 pp. Light signs of use on DJ. Book is just about 1-2 except for numerous pencil check marks. $6.00. 3550. THE ACCOMPANIST – AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDRÉ BENOIST (ed. John Anthony Maltese). Paganiniana Pub., Neptune City, NJ. 1978. 383 pp. Profusely illustrated. A fascinating and extremely candid look at dozens of the vocal and instrumental celebrities with whom Benoist was associated. -

The Birth of the Manhattan Opera Company

News From VHSource, LLC Vol 11 November 2013 The Birth of the Manhattan Opera Company It was during the summer of 1904 that the sauce pan Out of Nothing Comes Success! slipped quietly, but resolutely, from the back burner to the forefront when Oscar related to son Arthur his he 1906 New York City was totally unprepared for intention to build the “largest theatre in the world.” The the Manhattan Opera Company. Everybody knew Victoria was on firm profit making ground. There was Twho Oscar Hammerstein was – he built theatres – a monthly income from the rental of both the Theatre he tried to do opera in English – he was a REAL character, Republic to David Belasco and the Lew M. Fields good for an amazing quote almost any day – he wore a top Theatre to Lew Fields. For the first time in his career, hat, old fashioned formal clothes and always had a cigar in Oscar had a positive cash flow, and he was looking to his hand or mouth, lit or unlit – he and his son Willie were build once again. See Vol 9 Sept 2013 newsletter for a the kings of vaudeville. Oh yes, everyone knew who complete discussion of the second Manhattan Opera House Oscar was! No one was prepared for the Manhattan Opera and its acoustical perfection. Company. While little is actually known of Hammerstein’s The Oscar we have met over the past few months truly acoustical designs or methods, we did run across the believed in opera for the people and because this was following description in Hammerstein biographer America, opera in English. -

Opens His Second Season Scribner's

THE FTHTDAY OREGOJflAN, PORTLAND, NOVEMBER 17, 1907. I HAMME-RSTEI- N SCRIBNER'S OPENS HIS SECOND SEASONHONORS MANHATTAN OPERA HOUSE IS OPENED WITH "LA GIOCONDA " NORDICA AND CAMPANINI SHARE IN THE MAGAZINE A GREAT 1 908 YEAR "eornf's la m grmmt mootf m a g m z I n mnd W hm In eirwy Ammrl-cm- n hmmm. " WIIUR kilt WHITE. THE NEW SERIAL STORY THE TRAIL OF THE LONESOME PINE By JOHN FOX, JR. Author of "The Utclc Shepherd of Kingdom Com.' etc. The heroine, JUNE, is most ap- pealing both as s little girl and ss s frown -- up woman. The pathos of her childhood and the difficulties of her maturity sre depicted with that in-- ti active sympathy which unfailing- ly guides Mr. Fox masterly literary skill and shows him not only an artist bat s nre interpreter of hearts. The seene is jn the Kentucky mountain. The love story v is s charm i etf one. Mr. Yoho will illustrate "The Trail of the Lonesome Pine. A CHRONICLE OF FRIEND- SHIPS '. Reminiscences h? WILL H. LOW Three Article. Hluatraud by the Author. Artist Ufa in Paris ins eirfciisn la the Tim ins Circis nf the STEVENS0HS There can he no better picture of the life of an ambitious art student thirty yean sgo. in the days when Millet was still living at Barbizon. The gayer side of the life among the young students is depicted, and there are many delightful account of ROB- ERT LOUIS 5T EVEN 3 ON and his cousin Bob.4 thet art critic, who added much to the joy of Mr. -

ARSC Journal

"L'EXQUISE" MAGGIE TEYTE: Nuits d'ete • -Le s ctre de la rose; Absence (Berlioz) (Orch; Leslie Heward • Poeme de l'amour et de la mer, Qil.:....12. (Chausson) {Orch; Leighton Lucas); Shghgrazade (Ravel) (Royal Opera House Orch; Hugo Rignold); L'invitation au vo~e; Phidyle (Duparc) {Orch; Heward); Pelleas et Melisande-Voici ce gu'il ecrit; ... Tune sais pourguoi (Debussy); Apr~s un r~ve; Clair de lune; Le secret; Ici-bas!; Dans les ruines d'une abbaye; L'absent; ~; Les roses d'Isehan; .§2k (F~~~J; Chanson d'Estelle (Godard); Chanson triste; Extase DuparcJ; Le temps des lilas; Les papillons; Le colibri (Chausson); Troia Chansons de Bilitis; Fetes galantes, I, II; Ballade des fe11U11es de Paris; ~ (Debussy); Deux Epigrammes (Ravel; La rosee sainte (stravinsky); Si mes vers avaient des ailes; L'heure exquise; Offrande; En sourdine (Hahn); Heures d'ete Rhene-Baton); Vieille chanson de chasse (arr. Manning); Vieille chanson Webber); Clair de lune Szulc ; ~ {Massenet); King Arthur-Fairest isle of isles excelli~ Purcell); Now sleeps the crimson petal (Quilter); 0 thank me not (Franz; The Bayley beareth the bell away; Lullaby {Warlock); Sir John in Love-Greensleeves (Vaughan Williams); Comin' thro' the Rze; Oft in the stilly night (Trad.); Land of heart's desire (Kennedy-Fraser); Still as the night (with John McCormack, tenor) (Goetze); M:msieur Beaucaire-Philomel; I do not know (with chorus); ••• Lightly, lightly; What are the names (with Marion Green, baritone) {Messager); ~ Appointment-White roses {Russell); Mozart-tf:.re adore; L'adieu (Hahn); Because ( D' Hardelot) • Dame Maggie Teyte, soprano; Gerald Moore and Alfred Cortot, piano. -

AULIKKI RAUTAWAARA [S] ANTENORE

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs AULIKKI RAUTAWAARA [s] 1580. 12” Blue Telefunken E1795 [020549/020550]. PEER GYNT: Solvejgs Wiegenlied/ PEER GYNT: Solvejgs Lied (Grieg). Orch. dir. Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt. Few rubs, 2. $8.00. ANTENORE REALI [b] 1824. 12” Green Cetra 25130 [2-70930/2-70968]. ARLESIANA: Come due tizzi ardenti (Cilèa)/ ZAZÀ: Zazà, piccolo zingara (Leoncavallo). Orch. dir. Arturo Basile. Just about 1-2. $12.00. GEORGES RÉGIS [t] 2946. 10” Blue Pats. Victor 45025 [14122u/6013h]. ILLUSION- SÉRÉNADE (Barbirolli)/ PARAIS À TA FENÊTRE-SÉRÉNADE (Gregh). IMs. Minor rubs, 2-3. $10.00. HEINRICH REHKEMPER [b]. Schwerte, 1894- Munich, 1949. After working for a period as a machinist, Rehkemper studied singing in Hagen, Düsseldorf and finally Munich. His debut was in Colberg, 1919, and then he sang as a leading baritone at Stuttgart. From 1925 he was with the Munich Staatsoper where he achieved great popularity and musical success. He was equally at home on the con- cert stage and was considered as one of the great lieder interpreters of his era. During World War II, in addition HEINRICH REHKEMPER to singing, Rehkemper taught at the Mozarteum in Salzburg. 2694. 10” PW Green elec. Polydor 23148 [1689BH/1690½BH]. NICHT MEHR ZU DIR ZU GEHEN, Op. 32, No. 2/DIE BOTSCHAFT, Op. 47, No. 1 (both Brahms). Piano acc. Michael Raucheisen. IMs. Just about 1-2. $15.00. 2395. 10” PW Green elec. Polydor 23150 [1686BH/1687BH]. ZUR JOHANNISNACHT, Op. 60, No. 5 (Grieg)/IM KAHNE (Grieg). Piano acc. Michael Raucheisen. Just about 1-2. $15.00. HANS REINMAR [b] 3700. -

Red Sealf Aged Fifty

54 Series, whatever its shortcomings as a business venture, had the fortunate end result of stimulating Victor to produce a similar series. Columbia Red Sealf Aged Fifty had let it be known that they were "the only ones in the talking machine business who have the means to employ singers whose time is valued ROLAND GELATT pany to begin I'ecording operatic ce at several dollars per second." The lebrities thi'oughout Europe. In March rising young Victor Talking Machine 1902 this firm engaged Enrico Caruso Company would not allow this sort of HEN the popular Australian to record ten arias—the first truly talk to go unchallenged. It countered contralto Ada Crossley re satisfactory operatic discs in the his with plans of its own for a Victor Wcorded the first Victor Red tory of the phonograph—and this ses celebrity seiies. An agreement was Seal discs fifty years ago this month, sion was soon followed by others in effected with the Gramophone Com she did not so much establish a pre which such notables as Emma Calve. pany whereby Victor could issue the cedent as she did an institution. In Maurice Renaud. Mattia Battistini. former's operatic recordings in the 1903 "celebrity recording" as such and Pol Plangon took part. United States. At the same time, was no longer a novelty. During the Early in 1903 the Columbia Phono Victor laid plans for its own cata Nineties the studio of Lt. Gianni Bet- graph Company, of New York, fol logue of celebrity discs. The new tini on Fifth Avenue offered cylinder lowed suit.