ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/199 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 A . " f ft.S. &. ft. P. deed not Ucende Some Recent Additions Select Your Choruses conceit cuid.iccitzt fotidt&{ to the Catalog of Oliver Ditson Co. NOW PIANO SOLOS—SHEET MUSIC The wide variety of selections listed below, and the complete AND PUBLISHERS in the THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, AUTHORS BMI catalogue of choruses, are especially noted as compo- MYRA ADLER Grade Pr. MAUDE LAFFERTY sitions frequently used by so many nationally famous edu- payment of the performing fee. Christmas Candles .3-4 $0.40 The Ball in the Fountain 4 .40 correspondence below reaffirms its traditional stand regarding ?-3 Happy Summer Day .40 VERNON LANE cators in their Festival Events, Clinics and regular programs. BERENICE BENSON BENTLEY Mexican Poppies 3 .35 The Witching Hour .2-3 .30 CEDRIC W. -

The Perfect Fool (1923)

The Perfect Fool (1923) Opera and Dramatic Oratorio on Lyrita An OPERA in ONE ACT For details visit https://www.wyastone.co.uk/all-labels/lyrita.html Libretto by the composer William Alwyn. Miss Julie SRCD 2218 Cast in order of appearance Granville Bantock. Omar Khayyám REAM 2128 The Wizard Richard Golding (bass) Lennox Berkeley. Nelson The Mother Pamela Bowden (contralto) SRCD 2392 Her son, The Fool speaking part Walter Plinge Geoffrey Bush. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime REAM 1131 Three girls: Alison Hargan (soprano) Gordon Crosse. Purgatory SRCD 313 Barbara Platt (soprano) Lesley Rooke (soprano) Eugene Goossens. The Apocalypse SRCD 371 The Princess Margaret Neville (soprano) Michael Hurd. The Aspern Papers & The Night of the Wedding The Troubadour John Mitchinson (tenor) The Traveller David Read (bass) SRCD 2350 A Peasant speaking part Ronald Harvi Walter Leigh. Jolly Roger or The Admiral’s Daughter REAM 2116 Narrator George Hagan Elizabeth Maconchy. Héloïse and Abelard REAM 1138 BBC Northern Singers (chorus-master, Stephen Wilkinson) Thea Musgrave. Mary, Queen of Scots SRCD 2369 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Leader, Reginald Stead) Conducted by Charles Groves Phyllis Tate. The Lodger REAM 2119 Produced by Lionel Salter Michael Tippett. The Midsummer Marriage SRCD 2217 A BBC studio recording, broadcast on 7 May 1967 Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir John in Love REAM 2122 Cover image : English: Salamander- Bestiary, Royal MS 1200-1210 REAM 1143 2 REAM 1143 11 drowned in a surge of trombones. (Only an ex-addict of Wagner's operas could have 1 The WIZARD is performing a magic rite 0.21 written quite such a devastating parody as this.) The orchestration is brilliant throughout, 2 WIZARD ‘Spirit of the Earth’ 4.08 and in this performance Charles Groves manages to convey my father's sense of humour Dance of the Spirits of the Earth with complete understanding and infectious enjoyment.” 3 WIZARD. -

MASSENET and HIS OPERAS Producing at the Average Rate of One Every Two Years

M A S S E N E T AN D HIS O PE RAS l /O BY HENRY FIN T. CK AU THO R O F ” ” Gr ie and His Al y sia W a ner and H W g , g is or ks , ” S uccess in Music and it W How is on , E ta , E tc. NEW YO RK : JO HN LANE CO MPANY MCMX LO NDO N : O HN L NE THE BO DLEY HE D J A , A K N .Y . O MP NY N E W Y O R , , P U B L I S HE R S P R I NTI N G C A , AR LEE IB R H O LD 8 . L RA Y BRIGHAM YO UNG UNlVERS lTW AH PRO VO . UT TO MY W I FE CO NTENTS I MASSENET IN AMER . ICA. H . B O GRAP KET H II I IC S C . P arents and Chi dhoo . At the Conservatoire l d . Ha D a n R m M rri ppy ys 1 o e . a age and Return to r H P a is . C oncert a Successes . In ar Time ll W . A n D - Se sational Sacred rama. M ore Semi religious m W or s . P ro e or and Me r of n i u k f ss be I st t te . P E R NAL R D III SO T AITS AN O P INIO NS . A P en P ic ure er en ne t by Servi es . S sitive ss to Griti m h cis . -

De Senectute Cantorum

DE SENECTUTE CANTORUM By CARL VAN VECHTEN Downloaded from "T" AM not sure," writes Arthur Symons in his admirable essay I on Sarah Bernhardt, "that the best moment to study an artist is not the moment of what is called decadence. The first energy of inspiration is gone; what remains is the method, the mechanism, and it is that which alone one can study, as one http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ can study the mechanism of the body, not the principle of life itself. What is done mechanically, after the heat of the blood has cooled, and the divine accidents have ceased to happen, is precisely all that was consciously skillful in the performance of an art. To see all this mechanism left bare, as the form of a skeleton is left bare when age thins the flesh upon it, is to learn more easily all that is to be learnt of structure, the art which not art but nature has hitherto concealed with its merciful at University of Birmingham on March 21, 2015 covering." Mr. Symons, of course, had an actress in mind, but his argument can be applied to singers as well, although it is safest to remember that much of the true beauty of the human voice inevitably departs with the youth of its owner. Still, style in singing is not noticeably affected by age and an artist who possesses or who has acquired this quality very often can afford to make lewd gestures at Father Time. If good singing depended upon a full and sensuous tone such artists as Ronconi, Victor Maurel, Max Heinrich, Ludwig Wtillner, and Maurice Renaud would never have had any careers at all. -

View Catalogue

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA [email protected] • www.lubranomusic.com Telephone 516-922-2192 Catalogue 88 SUMMER POTPOURRI 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com Telephone 516-922-2192 1 CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). Please note that all material is in good antiquarian condition unless otherwise described. All items are offered subject to prior sale. We thus suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper right of our homepage. We ask that you kindly wait to receive our invoice to ensure availability before remitting payment. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. New York State sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. We accept payment by: - Credit card (VISA, Mastercard, American Express) - PayPal to [email protected] - Checks in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank - International money order - Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) - Automated Clearing House (ACH), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. -

New York As the Operatic Metropolis by Henry T

NEW YORK AS THE OPERATIC METROPOLIS BY HENRY T. FINCK HETHER New York really is the rar and Caruso in the same opera, because W operatic center of the universe, as the fame of either alone fills the house. some critics and observers claim, is a ques Grau used to delight in arranging all-star tion worth considering. Doubtless the casts that took one's breath away. Once, Metropolitan has a larger number of great when he gave "Les Huguenots" with singers than any foreign opera-house; but Sembrich, Nordica, Jean and Edouard de it is also true that there have been years Reszke, besides Maurel, and Plangon, he when the number of first-class artists asked two dollars extra for parquet seats; gathered under its roof was greater than but often he provided casts nearly or quite it is now. This is particularly the case as remarkable without raising the prices. with the lowest voices. Among fourteen We recall, for instance, "Carmen," with mezzo-sopranos and contraltos, Louise Calve, Fames, Jean and Edouard de Homer alone upholds the high standards Reszke; "Tristan und Isolde" with Lilli of the past; and while Allen Hinckley, Lehmann (or Nordica), Schumann- Andrea de Segurola, and Herbert Wither- Heink, Jean and Edouard de Reszke, and spoon are good bas^s, they do not'rank Bispham (or Van Rooy). These cannot with Edouard de Reszke, Emil Fischer, be equaled to-day. Nevertheless, some of and Pol Plangon. Among the baritones, the present Metropolitan casts are not at however, there are no fewer than seven all to be sneered at. -

The Music Trade Review

Music Trade Review -- © mbsi.org, arcade-museum.com -- digitized with support from namm.org THE MUSIC TRADE REVIEW GEISI, OTTOBONI, SANGIOKGI AND SALA, WITH OKCH. TENOR SOLO IN ITALIAN, ORCH. ACCOMP. LATEST RECORD LISTS. 10572 Luisa Miller, Quando le sere al placido 61170 Ernani—Act. 1. No. 9—Finale Verdi 10 (Verdi)^Record made in Milan LA SCALA CHORUS., WITH ORCII. Romeo Berti Victor Co.'s and Columbia Phonograph Co.'s 01171 Ernani—Act 2. No. 10—Esultiam (Day of 10 SOPRANO AND BARITONE DUET IN ITALIAN, ORCH. ACCOMP. Lists for March—Edison List Was Printed Gladness) Verdi 30050 Serenata (Schubert) BERNACCHI, COLAZZA AND DE LUNA, WITH ORCH. ...Mine. Gina Ciaparelli and Taurino Parvis Last Week in This Department. 61172 Ernani—Act 2. No. 11—Oro quant' oro 10 TENOR SOLO, ORCII. ACCOMP. (1 am the Bandit Ernani!) Verdi 30051 I'll Sing Thee Songs of Araby (Clay) CARONNA AND DE LUNA, WITH ORCH. Henry Burr NEW VICTOR RECORDS. 30052 G. A. It. Patrol (R. Fassett) 01173 Ernani—Act 2. No. 12—La vedremo, o Prince's Military Band veglio audace (I Will Prove, Audacious 10 30053 Patrol of the Scouts (E. Boccalari) No. ARTHUH PKYOR S BAM). Size. Greybeard) Verdi 5005 Blue Jackets March Bennet 10 GRISI, CIGADA, OTTOBONI AND LA SCALA CHORUS, Prince's Military Band 31609 La Lettre de Manon Gillet 12 WITH ORCH. BARITONE AND TENOR DUET, ORCH. ACCOMP. SOUSA'S BAND. 61174 Ernani—Act 2. No. 13—Vieni meco (Come 10 30054 In a Chimney Corner (On a winter's night) Thou Dearest Maiden) Verdi (Harry Von Tilzer) Collins and Harlan 4981 The Preacher and the Bear Sorensen 10 VAUDEVILLE SPECIALTY, OUCH. -

Irving Ritterman Collection of Autographs and Musical Memorabilia

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9m3nd0xq No online items Finding Aid for the Irving Ritterman Collection of Autographs and Musical Memorabilia 1901-1961 Processed by Performing Arts Special Collections staff. UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm ©2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 112-M 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Irving Ritterman Collection of Autographs and Musical Memorabilia, Date (inclusive): 1901-1961 Collection number: 112-M Creator: Ritterman, Irving Extent: 2 boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: The majority of the collection consists of autographs and autographed photographs of famous composers, conductors, and vocalists from the early 20th century. Language of Material: Collection materials in English Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

|What to Expect from Cendrillon

| WHAT TO EXPECT FROM CENDRILLON IT IS THE MOST BELOVED FAIRY TALE OF ALL TIME: A YOUNG WOMAN THE WORK: of unmatched grace, beauty, and goodness overcomes the abuse of her CENDRILLON stepfamily, profits from the help of a fairy godmother, wins the heart of a An opera in four acts, sung in French royal suitor, and lives happily ever after. For almost two thousand years, Music by Jules Massenet versions of the Cinderella story have spread across the globe, inspiring inter- Libretto by Henri Cain pretation by myriad authors, playwrights, musicians, and filmmakers. In the Based on the fairy tale fin-de-siècle opera by Jules Massenet, the virtue of the title character is made Cendrillon by Charles Perrault more poignant by her sadness—occasionally, even her despair. In addition First performed May 24, 1899 to incorporating the iconic elements familiar from Charles Perrault’s fairy at the Opéra-Comique, Paris, France tale—the carriage formed from a pumpkin, the midnight curfew, and the singular glass slipper—Massenet infuses his opera with comedy, romance, PRODUCTION and wistfulness. Bertrand de Billy, Conductor This new production by director Laurent Pelly quite literally brings the Laurent Pelly, Production storybook tale to life. Inspired by an edition of Perrault’s Cendrillon as illus- Barbara de Limburg, Set Designer trated by Gustave Doré that Pelly read as a child, the production is steeped Laurent Pelly, Costume Designer in the physical, typographical materials of the fairy tale. The set evokes Duane Schuler, Lighting Designer the pages of a book, with black and white text forming its walls, and the shapes of characters and props appearing as large cut-out letters. -

THE RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE Given Below Is the Featured Artist(S) of Each Issue (D=Discography, B=Biographical Information)

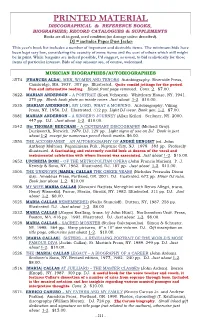

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, BIOGRAPHIES; RECORD CATALOGUES & SUPPLEMENTS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket This year’s book list includes a number of important and desirable items. The minimum bids have been kept very low, considering the scarcity of some items and the cost of others which still might be in print. While bargains are indeed possible, I’d suggest, as usual, to bid realistically for those items of particular interest. Bids of any amount are, of course, welcomed. MUSICIAN BIOGRAPHIES/AUTOBIOGRAPHIES 3574. [FRANCES ALDA]. MEN, WOMEN AND TENORS. Autobiography. Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA. 1937. 307 pp. Illustrated. Quite candid jottings for the period. Fun and informative reading. Blank front page removed. Cons. 2. $7.00. 3622. MARIAN ANDERSON – A PORTRAIT (Kosti Vehanen). Whittlesey House, NY. 1941. 270 pp. Blank book plate on inside cover. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3535. [MARIAN ANDERSON]. MY LORD, WHAT A MORNING. Autobiography. Viking Press, NY. 1956. DJ. Illustrated. 312 pp. Light DJ wear. Book gen. 1-2. $7.00. 3581. MARIAN ANDERSON – A SINGER’S JOURNEY (Allan Keiler). Scribner, NY. 2000. 447 pp. DJ. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3542. [Sir THOMAS] BEECHAM – A CENTENARY DISCOGRAPHY (Michael Gray). Duckworth, Norwich. 1979. DJ. 129 pp. Light signs of use on DJ. Book is just about 1-2 except for numerous pencil check marks. $6.00. 3550. THE ACCOMPANIST – AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDRÉ BENOIST (ed. John Anthony Maltese). Paganiniana Pub., Neptune City, NJ. 1978. 383 pp. Profusely illustrated. A fascinating and extremely candid look at dozens of the vocal and instrumental celebrities with whom Benoist was associated. -

The Vocality of Sibyl Sanderson in Massenet's Manon and Esclarmonde Tamara D. Thompson

The Vocality of Sibyl Sanderson in Massenet’s Manon and Esclarmonde Tamara D. Thompson Submitted to the Royal College of Music, London in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology May, 2016 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Figures iv Tables vi Examples vii INTRODUCTION 1 Research Aims and Objectives 1 Key Definitions 3 Sources and Methodology 4 Literature Review 14 Why Manon and Esclarmonde? 25 CHAPTER ONE SIBYL SANDERSON: LA BELLE CRÉATRICE 27 Biographical Information 27 Personality 34 Physical Appearance 39 CHAPTER TWO TRAINING LA BELLE SIBYL: THE ARTISTIC EDUCATION OF SIBYL SANDERSON 47 Conservatoire and California (1881–1885) 47 Paris (1885–1887) 56 Composers as Coaches (1887–1892) 78 Paris (1892–1896) 83 CHAPTER THREE VOCALITY: LA VOIX EST UN RAVISSEMENT 100 Sound 105 Characterisation 108 Vocal Demands in Manon 113 Vocal Demands in Esclarmonde 119 iii CHAPTER FOUR MANON: SANDERSON’S RE-CREATION OF THE RÔLE 128 Manon: History of the Opera 128 Manon: How Story and Staging Inform Vocality 136 Manon: Score Annotations 157 Musical Analysis: ‘Je suis encore tout étourdie’ 183 Musical Analysis of ‘Gavotte’ 206 Musical Analysis: ‘Fabliau’ 217 CHAPTER FIVE ESCLARMONDE: SANDERSON’S CREATION OF THE RÔLE 233 Esclarmonde: History of the Opera and Sanderson as la créatrice 233 Esclarmonde: How Story and Staging Inform Vocality 257 Musical Analysis: Esprits de l’air’ 278 Musical Analysis: Ah ! Roland ! 295 CONCLUSION 307 Research Questions and Answers 307 Contributions to Knowledge 311 Future Research Plans 316 BIBLIOGRAPHY 318 iv Figures Figure 1: List of Sources ..................................................................................................... 4 Figure 2: Letter excerpt .................................................................................................... -

The Birth of the Manhattan Opera Company

News From VHSource, LLC Vol 11 November 2013 The Birth of the Manhattan Opera Company It was during the summer of 1904 that the sauce pan Out of Nothing Comes Success! slipped quietly, but resolutely, from the back burner to the forefront when Oscar related to son Arthur his he 1906 New York City was totally unprepared for intention to build the “largest theatre in the world.” The the Manhattan Opera Company. Everybody knew Victoria was on firm profit making ground. There was Twho Oscar Hammerstein was – he built theatres – a monthly income from the rental of both the Theatre he tried to do opera in English – he was a REAL character, Republic to David Belasco and the Lew M. Fields good for an amazing quote almost any day – he wore a top Theatre to Lew Fields. For the first time in his career, hat, old fashioned formal clothes and always had a cigar in Oscar had a positive cash flow, and he was looking to his hand or mouth, lit or unlit – he and his son Willie were build once again. See Vol 9 Sept 2013 newsletter for a the kings of vaudeville. Oh yes, everyone knew who complete discussion of the second Manhattan Opera House Oscar was! No one was prepared for the Manhattan Opera and its acoustical perfection. Company. While little is actually known of Hammerstein’s The Oscar we have met over the past few months truly acoustical designs or methods, we did run across the believed in opera for the people and because this was following description in Hammerstein biographer America, opera in English.