Play It Again, Duke: Jazz Performance, Improvisation, and the Construction of Spontaneity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3

1. The Stevedore’s Serenade (Edelstein-Gordon-Ellington) 2. La Dee Doody Doo (Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3. A Blues Serenade (Parish-Signorelli-Grande-Lytell) 4. Love In Swingtime (Lambert-Richards-Mills) 5. Please Forgive Me (Ellington-Gordon-Mills) 6. Lambeth Walk (Furber-Gay) 7. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 8. Hip Chic (Ellington) 9. Buffet Flat (Ellington) 10. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 11. There’s Something About An Old Love (Mills-Fien-Hudson) 12. The Jeep Is Jumpin’ (Ellington-Hodges) 13. Krum Elbow Blues (Ellington-Hodges) 14. Twits And Twerps (Ellington-Stewart) 15. Mighty Like The Blues (Feather) 16. Jazz Potpourri (Ellington) 17. T. T. On Toast lEllington-Mills) 18. Battle Of Swing (Ellington) 19. Portrait Of The Lion (Ellington) 20. (I Want) Something To Live For (Ellington-Strayhorn) 21. Solid Old Man (Ellington) 22. Cotton Club Stomp (Carney-Hodges-Ellington) 23. Doin’The Voom Voom (Miley-Ellington) 24. Way Low (Ellington) 25. Serenade To Sweden (Ellington) 26. In A Mizz (Johnson-Barnet) 27. I’m Checkin’ Out, Goo’m Bye (Ellington) 28. A Lonely Co-Ed (Ellington) 29. You Can Count On Me (Maxwell-Myrow) 30. Bouncing Buoyancy (Ellington) 31. The Sergeant Was Shy (Ellington) 32. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 33. Little Posey (Ellington) 34. I Never Felt This Way Before (Ellington) 35. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 36. Tootin Through The Roof (Ellington) 37. Weely (A Portrait Of Billy Strayhorn) (Ellington) 38. Killin’ Myself (Ellington) 39. Your Love Has Faded (Ellington) 40. Country Gal (Ellington) 41. Solitude (Ellington-De Lange-Mills) 42. Stormy Weather (Arlen-Köhler) 43. -

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and His Kentucky Club Orchestra

MUNI 20070315 DUKE ELLINGTON C D 1 1. East St.Louis Toodle-Oo (Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra. NY, November 29, 1926. 2. Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington-Rudy Jackson-Bubber Miley) 3:14 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, October 26, 1927. 3. Harlem River Quiver [Brown Berries] (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields-Danni Healy) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, December 19, 1927. 2:48 4. Tiger Rag [Part 1] (Nick LaRocca) 2:52 5. Tiger Rag [Part 2] 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, January 8, 1929. 6. A Nite at the Cotton Club 8:21 Cotton Club Stomp (Duke Ellington-Johnny Hodges-Harry Carney) Misty Mornin’ (Duke Ellington-Arthur Whetsol) Goin’ to Town (D.Ellington-B.Miley) Interlude Freeze and Melt (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields) Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra. NY, April 12, 1929. 7. Dreamy Blues [Mood Indigo ] (Albany Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, October 17, 1930. 8. Creole Rhapsody (Duke Ellington) 8:29 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. Camden, New Jersey, June 11, 1931. 9. It Don’t Mean a Thing [If It Ain’t Got That Swing] (D.Ellington-I.Mills) 3:12 Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra. NY, February 2, 1932. 10. Ellington Medley I 7:45 Mood Indigo (Barney Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) Hot and Bothered (Duke Ellington) Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, February 3, 1932. 11. Sophisticated Lady (Duke Ellington-Irving Mills-Mitchell Parish) 3:44 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

JAMU 20141112-2 – Duke Ellington: BLACK, BROWN and BEIGE (1943, 1958, 1965-71)

JAMU 20141112-2 – Duke Ellington: BLACK, BROWN AND BEIGE (1943, 1958, 1965-71) Carnegie Hall, New York City, January 23, 1943: 1. Black 20:44 2. Brown 10:10 3. Beige 13:29 Rex Stewart, Harold Baker, Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Tricky Sam Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster, Harry Carney, Otto Hardwicke, Chauncey Haughton-reeds; Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Junior Raglin-b; Sonny Greer-dr; Betty Roche-voc; Billy Strayhorn-assistant arranger. LP Prestige P-34004 (1977) / CD Prestige 2PCD-34004-2 (1991) Columbia Studios, New York City, February 4, 11 & 12, 1958: 1. Part I 8:17 2. Part II 6:14 3. Part III (Light) 6:26 4. Part IV (Come Sunday) 7:58 5. Part V (Come Sunday) 3:46 6. Part VI (23rd Psalm) 3:01 (plus 10 bonus tracks on CD reissue) Cat Anderson, Harold Baker, Clark Terry-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Quentin Jackson, Britt Woodman-tb; John Sanders-vtb; Jimmy Hamilton-cl; Russell Procope-cl, as; Bill Graham-as; Paul Gonsalves-ts; Harry Carney-bs; Duke Ellington-p; Jimmy Woode-b; Sam Woodyard-dr; Mahalia Jackson-voc. LP Columbia CS 8015 (1958) / CD Columbia/Legacy CK 65566 (1999) New York, March 4, 1965 & May 6, 1971; Chicago, March 31, 1965 & May 18, 1965: 1. Black 8:09 2. Comes Sunday 5:59 3. Light 6:29 4. West Indian Dance 2:15 5. Emancipation Celebration 2:36 6. The Blues 5:23 7. Cy Runs Rock Waltz 2:18 8. Beige 2:24 9. -

ELLINGTON '2000 - by Roger Boyes

TH THE INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN22 year of publication OEMSDUKE ELLINGTON MUSIC SOCIETY | FOUNDER: BENNY AASLAND HONORARY MEMBER: FATHER JOHN GARCIA GENSEL As a DEMS member you'll get access from time to time to / jj£*V:Y WL uni < jue Duke material. Please bear in mind that such _ 2000_ 2 material is to be \ handled with care and common sense.lt " AUQUSl ^^ jj# nust: under no circumstances be used for commercial JUriG w «• ; j y i j p u r p o s e s . As a DEMS member please help see to that this Editor : Sjef Hoefsmit ; simple rule is we \&! : T NSSESgf followed. Thus will be able to continue Assisted by: Roger Boyes ^ fueur special offers lil^ W * - DEMS is a non-profit organization, depending on ' J voluntary offered assistance in time and material. ALL FOR THE L O V E D U K E !* O F Sponsors are welcomed. Address: Voort 18b, Meerle. Belgium - Telephone and Fax: +32 3 315 75 83 - E-mail: [email protected] LOS ANGELES ELLINGTON '2000 - By Roger Boyes The eighteenth international conference of the Kenny struck something of a sombre note, observing that Duke Ellington Study Group took place in the we’re all getting older, and urging on us the need for active effort Roosevelt Hotel, 7000 Hollywood Boulevard, Los to attract the younger recruits who will come after us. Angeles, from Wednesday to Sunday, 24-28 May This report isn't the place for pondering the future of either 2000. The Duke Ellington Society of Southern conferences or the wider activities of the Ellington Study Groups California were our hosts, and congratulations are due around the world. -

60 / Running Head

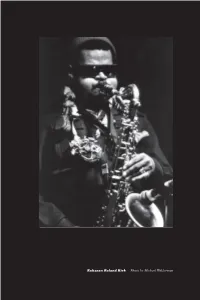

60 / running head RahsaRahsaaRahsaan Roland Kirk Photo by Michael Wilderman monstrosioso 1965: The Creeper The fussy encyclopedic gravity of the Hammond B-3 overcome and the electric organ lofted to hard-bop orbit, still trailing diapasons of his mother’s church music and the boogie-woogie tap-dance routines of his father’s band—The Incredible Jimmy Smith proclaimed the block letters on a score of albums since the 1956 breakout recordings on Blue Note, those words celebrating a nearly miraculous mating of technology and soul. The thing had first stirred to life at a club in Atlantic City where he heard Wild Bill Davis make the Hammond roar like a big wave. It was a monster, upsurged through chocked, choppy chords and backwashed through rilling legatos, wattage enough there to power the entire Basie band. Davis was gruff, brash, gloriously loud, a bumptious lumbering at- tack, great swoops down on the keys and shameless ripsaw goosings of reverb and tremolo, the organ not so much singing as signaling, the music stripped to pure swelling impulse. For a piano player schooled in the over- brimming muscular lines of Art Tatum and the stabbing, nervous prances of Bud Powell, it was almost risible, the goddamned wired-up thing rock- ing on stage like a gurgling showboat. Fats Waller on “Jitterbug Waltz” coaxed over the organ with a percolating finesse as if running a trapeze artist up a swaying wire, but Davis almost seemed clumsy by design, as if in awe of the organ’s powers yet unable to forego provoking them. -

The Highest Note in the Century Since His Birth, Duke Ellington Has Been the Most Important Composer of Any Music, Anywhere Blumenthal, Bob

Document 1 of 1 The highest note In the century since his birth, Duke Ellington has been the most important composer of any music, anywhere Blumenthal, Bob. Boston Globe [Boston, Mass] 25 Apr 1999: 1. Abstract The late Duke Ellington, whose 100th birthday will be celebrated on Thursday, disliked the word "jazz." As he famously remarked, the only subsets of music he recognized were good and bad. Rather than stress categorical distinctions, Ellington preferred to celebrate artists and works that were, in another of his oft-quoted phrases, "beyond category." The magnitude of Ellington's legacy should be clear to all who can hear, and even to those who can only count. Just look at the numbers. From 1914, when he wrote "Soda Fountain Rag" as an aspiring pianist in his native Washington, D.C., until shortly before his death, on May 24, 1974, Ellington was responsible for nearly 2,000 documented compositions. From 1923, when he first gained employment in New York for his Washingtonians at Barron Wilkins's Harlem nightclub, he kept an orchestra together through boom andbust. The notion of writing for specific individuals as part of an ensemble reached its highest form of expression with Ellington. Rather than simply creating music for a three-piece trombone section, he crafted lines that fit the plungered growl of Joe "Tricky Sam" Nanton, the fluency of Lawrence Brown, and the warmth of Jual Tizol's valved instrument; and he applied this practice to every chair in the band. This led Ellington to collect musicians whose "tonal personality" (another favor-ite image) inspired him, ratherthan those who might simply blendinto an undifferentiated orchestral mass. -

Duke Ellington's Sophisticated Ladies

study guide contents The Play Meet the “Duke” Cotton Club Harlem Renaissance Jazz Music The U Street Connection Musical Revue Dancing Brothers Additional Resources the play Duke Ellington’s Sophisticated Ladies is a musical revue set during America’s Big Band Era (1920-1945). Every song tells a story, and together they paint a colorful pic- ture of Duke Ellington’s life and career as a musician, composer and band leader. Duke Ellington’s Act I highlights the Duke’s early days on tour, while Sophisticated Act II offers a glimpse into his private life and his often Ladies troubled relationships with women. Now Playing at the Lincoln Theatre April 9 – May 30, 2010 Concept by Donald McKayle Based on the music of Duke Ellington Musical and dance arrangements by Lloyd Mayers Vocal arrangements by Malcolm Dodds and Lloyd Mayers Original music direction by Mercer Ellington Directed by Charles Randolph-Wright Choreographed by Maurice Hines meet the “Duke” Harlem Renaissance “His music sounds “Drop me off in Harlem — any place in Harlem. like America.” There’s someone waiting there who makes – Wynton Marsalis it seem like heaven up in Harlem.” dward Kennedy rom the mid-1920s until the early 1930s, the African-American community “Duke” Ellington was in Harlem enjoyed a surging period of cultural, creative and artistic growth. born in Washington, Spurred by an emerging African-American middle class and the freedom D.C. on April 29, after slavery, the Harlem Renaissance began as a literary movement. Authors 1899.E He began playing the Fsuch as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston expressed the spirit of African- piano at age 7, and by 15, Americans and shed light on the black experience. -

Black, Brown and Beige

Jazz Lines Publications Presents black, brown, and beige by duke ellington prepared for Publication by dylan canterbury, Rob DuBoff, and Jeffrey Sultanof complete full score jlp-7366 By Duke Ellington Copyright © 1946 (Renewed) by G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP) International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by Permission. Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2017 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA duke ellington series black, brown, and beige (1943) Biographies: Edward Kennedy ‘Duke’ Ellington influenced millions of people both around the world and at home. In his fifty-year career he played over 20,000 performances in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East as well as Asia. Simply put, Ellington transcends boundaries and fills the world with a treasure trove of music that renews itself through every generation of fans and music-lovers. His legacy continues to live onward and will endure for generations to come. Wynton Marsalis said it best when he said, “His music sounds like America.” Because of the unmatched artistic heights to which he soared, no one deserves the phrase “beyond category” more than Ellington, for it aptly describes his life as well. When asked what inspired him to write, Ellington replied, “My men and my race are the inspiration of my work. I try to catch the character and mood and feeling of my people.” Duke Ellington is best remembered for the over 3,000 songs that he composed during his lifetime. -

1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993

dF Universitycrldaho LIoNEL HmPToN/CHEVRoN JnzzFrsrr\Al 1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993 t./¡ /ìl DR. LYNN J. SKtNNER, Jazz Festival Executive Director VtcKt KtNc, Program Coordinator BRTNoR CAtN, Program Coordinator J ¡i SusnN EHRSTINE, Assistant Coordinator ltl ñ 2 o o = Concert Producer: I É Lionel Hampton, J F assisted by Bill Titone and Dr. Lynn J. Skinner tr t_9!Ð3 ü This project is supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts We Dedicate this 1993 Lionel Hømpton/Chevron Jøzz Festivül to Lionel's 65 Years of Devotion to the World of Juzz Page 2 6 9 ll t3 r3 t4 l3 37 Collcgc/Univcrsity Compctition Schcdulc - Thursday, Feh. 25, 1993 43 Vocal Enserrrbles & Vocal Conrbos................ Harnpton Music Bldg. Recital Hall ...................... 44 45 46 47 Vocal Compctition Schcrlulc - Fridav, Fcli. 2ó, 1993 AA"AA/AA/Middle School Ensenrbles ..... Adrrrin. Auditoriunr 5l Idaho Is OurTenitory. 52 Horizon Air has more flights to more Northwest cities A/Jr. High/.Ir. Secondary Ensenrbles ........ Hampton Music Blclg. Recital Hall ...............,...... 53 than any other airline. 54 From our Boise hub, we serve the Idaho cities of Sun 55 56 Valley, Idaho Falls, Lewiston, MoscowÆullman, Pocatello and AA/A/B/JHS/MIDS/JR.SEC. Soloists ....... North Carnpus Cenrer ll ................. 57 Twin Falls. And there's frequent direct service to Portland, lnstrurncntal Corupctilion'Schcrlulc - Saturday, Fcll. 27, 1993 Salt Lake City, Spokane and Seattle as well. We also offer 6l low-cost Sun Valley winter 8,{. {ÀtûåRY 62 and summer vacation vt('8a*" å.t. 63 packages, including fOFT 64 airfare and lodging. -

10-25-13 Jazz Ensemble

Williams College Department of Music Williams Jazz Ensemble Kris Allen, Director Introduction: Smile Please - Stevie Wonder, arranged by Kris Allen Young up- and -coming composers and arrangers of the New York scene: After the Morning - John Hicks, arranged by David Gibson Arabia - Curtis Fuller, arranged by Chris Casey Noctilucent Shift - Sara Jacovino Small Combo: Passion Dance - McCoy Tyner Jonathan Dely '15, trumpet; Taylor Halperin '14, piano; Greg Ferland '16, bass; Brian Levine '16, drums Coached by Avery Sharpe My Funny Valentine - Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart, arranged by Max Seigel SKJ Blues - Milt Jackson, arranged by James Burton Going Somewhere - James Burton Saxophones Trumpets Rhythm Nikki Caravelli '16 Richard Whitney '16 Nathaniel Vilas '17 - piano Max Dietrick '16 Jonathan Dely '15 Austin Paul '16 - vibraphone Jackson Myers '17 Will Hayes '14 Jack Schweighauser '15 - guitar Samantha Polsky '17 Byron Perpetua '14 Greg Ferland '16 - bass Sammi Jo Stone '17 Paul Heggeseth Brian Levine '16 - drumset Trombones Hartley Greenwald '16 Jeff Sload '17 Allen Davis '14 Nico Ekasumara '14 Friday, October 25, 2013 8:00 p.m. Chapin Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts Please turn off cell phones. No photography or recording is permitted. Upcoming Events: See music.williams.edu for full details and additional happenings as well as to sign up for the weekly e-newsletters. 10/27 3:00pm Visiting Artists Freddie Bryant & Shubhendra Rao Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall 10/29 4:15pm Master Class with Visiting Artist Jonathan Biss, piano Chapin Hall