Constellations of Struggle Luisa Moreno, Charlotta Bass, and the Legacy for Ethnic Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

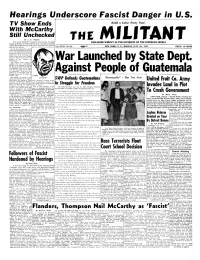

Fascist Danger in U.S

Hearings Underscore Fascist Danger in U.S. ------------------------------------------- ® --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- TV Show Ends Build a Labor Party Now! With McCarthy Still Unchecked By L. P. Wheeler The Army-McCarthy hearings closed June 17 after piling up 36 days of solid evidence that a fascist movement called McCarthyism has sunk roots deep into the govern ment and the military. For 36 days McCarthy paraded before some 20,000,000 TV viewers as the self-appointed custodian of America’s security. No one chal lenged him when he turned the Senate caucus room into a fascist forum to lecture with charts and pointer on the “menace of Communism.” War Launched by State Dept. This ghastly farce seems in credible. Yet the “anti-<McCar- thyites’’ in the hearing sat before the Wisconsin Senator and nodded in agreement while he hit them over the head with the “menace of Communism.” And then they blinked as if astonished when he Against People of Guatemala brought down his “21 years of treason” club. The charge of treason is the M cCa r t h y “Eventually” - But Not Now ready-made formula of the Amer SWP Defends Guatemalans ican fascists for putting a “save many unionists, minority people United Fruit Co. -

Conspiracy of Peace: the Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956

The London School of Economics and Political Science Conspiracy of Peace: The Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956 Vladimir Dobrenko A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 90,957 words. Statement of conjoint work I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by John Clifton of www.proofreading247.co.uk/ I have followed the Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition, for referencing. 2 Abstract This thesis deals with the Soviet Union’s Peace Campaign during the first decade of the Cold War as it sought to establish the Iron Curtain. The thesis focuses on the primary institutions engaged in the Peace Campaign: the World Peace Council and the Soviet Peace Committee. -

Charlotta A. Bass Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6c60052d No online items Register of the Charlotta A. Bass Papers Processed by The Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research staff; supplementary encoding and revision supplied by Xiuzhi Zhou. Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research 6120 S. Vermont Avenue Los Angeles, California 90044 Phone: (323) 759-6063 Fax: (323) 759-2252 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.socallib.org © 2000 Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. All rights reserved. Register of the Charlotta A. Bass MSS 002 1 Papers Register of the Charlotta A. Bass Papers Collection number: MSS 002 Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research Los Angeles, California Contact Information: Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research 6120 S. Vermont Avenue Los Angeles, California 90044 Phone: (323) 759-6063 Fax: (323) 759-2252 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.socallib.org Processed by: Mary F. Tyler Date completed: Nov. 1983 © 2000 Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Charlotta A. Bass Papers Collection number: MSS 002 Creator: Bass, Charlotta A., 1874-1968 Extent: 8 document cases 3 cubic feet Repository: Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. Los Angeles, California Language: English. Access The collection is available for research only at the Library's facility in Los Angeles. The Library is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday. Researchers are encouraged to call or email the Library indicating the nature of their research query prior to making a visit. -

Policies for an Equitable and Inclusive Los Angeles Authors

September 2020 No Going Back POLICIES FOR AN EQUITABLE AND INCLUSIVE LOS ANGELES AUTHORS: 1 Contents Foreword ................................................................................... 3 Land Acknowledgement .......................................................... 8 Acknowledgements ................................................................. 9 Executive Summary ............................................................... 11 Context: Los Angeles and the State Budget ........................ 16 Framing Principle: Infusing Equity into all Policies ............. 19 Policy Section 1: Economic Stress ......................................... 20 Policy Section 2: Black Life in Los Angeles .......................... 39 Policy Section 3: Housing Affordability ................................ 52 Policy Section 4: Homelessness ........................................... 65 Policy Section 5: Healthcare Access .................................... 78 Policy Section 6: Healthcare Interventions ........................86 Policy Section 7: Internet as a Right .................................... 95 Policy Section 8: Education ................................................ 103 Policy Section 9: Child and Family Well-Being .................. 113 Policy Section 10: Mental Health ........................................ 123 Policy Section 11: Youth ....................................................... 133 Policy Section 12: Immigrants .............................................148 Policy Section 13: Alternatives to Incarceration .............. -

December 2020

African American Experience Infusion Monthly Digest Black Women in Politics November/ December 2020. U.S. Rep. Shirley Chisholm announcing her candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination on Jan. 25, 1972. Photo: Thomas J. O'Halloran hhttps://www.rutgers.edu/news/black-women-still-underrepresented-american-politics-show-continued-gai ns by Jon Rehm on November Each month a new topic will be spotlighted in this newsletter. The goal is for each school to have access to a consistent source of information to assist in the infusion of the African American experience. With Sen. Kamala Harris the presumptive Vice President this month’s topic is the African American women in politics. As of the 2018 election, African american women were underrepresented in all areas of politics never having served as governor of a state, comprising 3.6 percent of the members of Congress and 3.7 percent of state legislators nationwide, less than 1 percent of elected executive officials, and of the mayors of the 100 most populous U.S. cities, five are black women (Branson. 2018). Yet African American women should be a force in politics. African american Women vote at a higher percentage than any other gender or racial group (Galofaro and Stafford, 2020). More and more African American Women are running and with base that votes, winning seats across the country. Resources U.S. House of Representatives website- Includes biographies Suffrage for Black Women- video and lesson plan Stacy Abrams- served in the Georgia House of Representatives from 2007-2017 and minority leader from 2011-2017. In 2018 she became the First African American woman to be the nominee for governor of a state by a major party. -

California Un-American Activities Committees Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft9p3007qg No online items Inventory of the California Un-American Activities Committees Records Processed by Archives Staff California State Archives 1020 "O" Street Sacramento, California 95814 Phone: (916) 653-2246 Fax: (916) 653-7363 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.sos.ca.gov/archives/ © 2000 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Inventory of the California 93-04-12; 93-04-16 1 Un-American Activities Committees Records Inventory of the California Un-American Activities Committees Records Collection number: 93-04-12; 93-04-16 California State Archives Office of the Secretary of State Sacramento, California Processed by: Archives Staff Date Completed: March 2000; Revised August 2014 Encoded by: Jessica Knox © 2000 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: California Un-American Activities Committees Records Dates: 1935-1971 Collection number: 93-04-12; 93-04-16 Creator: Senate Fact-Finding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities, 1961-1971;Senate Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, 1947-1960;Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities in California, 1941-1947;Assembly Relief Investigating Committee on Subversive Activities, 1940-1941 Collection Size: 48 cubic feet and 13 boxes Repository: California State Archives Sacramento, California Abstract: The California Un-American Activities Committees (CUAC) files (identification numbers 93-04-12 and 93-04-16) span the period 1935-1971 and consist of eighty cubic feet. The files document legislative investigations of labor unions, universities and colleges, public employees, liberal churches, and the Hollywood film industry. Later the committee shifted focus and concentrated on investigating communist influences in America, racial unrest, street violence, anti-war rallies, and campus protests. -

ITALIANS in the UNITED STATES DURING WORLD WAR II Mary

LAW, SECURITY, AND ETHNIC PROFILING: ITALIANS IN THE UNITED STATES DURING WORLD WAR II Mary Elizabeth Basile Chopas A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Wayne E. Lee Richard H. Kohn Eric L. Muller Zaragosa Vargas Heather Williams ©2013 Mary Elizabeth Basile Chopas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Mary Elizabeth Basile Chopas: Law, Security, and Ethnic Profiling: Italians in the United States During World War II (under the direction of Wayne E. Lee) The story of internment and other restrictions during World War II is about how the U.S. government categorized persons within the United States from belligerent nations based on citizenship and race and thereby made assumptions about their loyalty and the national security risk that they presented. This dissertation examines how agencies of the federal government interacted to create and enact various restrictions on close to 700,000 Italian aliens residing in the United States, including internment for certain individuals, and how and why those policies changed during the course of the war. Against the backdrop of wartime emergency, federal decision makers created policies of ethnic-based criteria in response to national security fears, but an analysis of the political maturity of Italian Americans and their assimilation into American society by World War II helps explain their community’s ability to avoid mass evacuation and internment. Based on the internment case files for 343 individuals, this dissertation provides the first social profile of the Italian civilian internees and explains the apparent basis for the government’s identification of certain aliens as “dangerous,” such as predilections for loyalty to Italy and Fascist beliefs, as opposed to the respectful demeanor and appreciation of American democracy characterizing potentially good citizens. -

African American History of Los Angeles

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: African American History of Los Angeles Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources NOVEMBER 2017 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Context: African American History of Los Angeles Certified Local Government Grant Disclaimers The activity that is the subJect of this historic context statement has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975 as amended, the Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination based on race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity National Park Service 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington -

Battle of the Brains: Election-Night Forecasting at the Dawn of the Computer Age

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: BATTLE OF THE BRAINS: ELECTION-NIGHT FORECASTING AT THE DAWN OF THE COMPUTER AGE Ira Chinoy, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Emeritus Maurine Beasley Philip Merrill College of Journalism This dissertation examines journalists’ early encounters with computers as tools for news reporting, focusing on election-night forecasting in 1952. Although election night 1952 is frequently mentioned in histories of computing and journalism as a quirky but seminal episode, it has received little scholarly attention. This dissertation asks how and why election night and the nascent field of television news became points of entry for computers in news reporting. The dissertation argues that although computers were employed as pathbreaking “electronic brains” on election night 1952, they were used in ways consistent with a long tradition of election-night reporting. As central events in American culture, election nights had long served to showcase both news reporting and new technology, whether with 19th-century devices for displaying returns to waiting crowds or with 20th-century experiments in delivering news by radio. In 1952, key players – television news broadcasters, computer manufacturers, and critics – showed varied reactions to employing computers for election coverage. But this computer use in 1952 did not represent wholesale change. While live use of the new technology was a risk taken by broadcasters and computer makers in a quest for attention, the underlying methodology of forecasting from early returns did not represent a sharp break with pre-computer approaches. And while computers were touted in advance as key features of election-night broadcasts, the “electronic brains” did not replace “human brains” as primary sources of analysis on election night in 1952. -

Robert W. Kenny Papers, 1823-1975

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf3199n6b1 No online items Register of the Robert W. Kenny Papers, 1823-1975 Processed by Mary F. Tyler; supplementary encoding and revision supplied by Xiuzhi Zhou. Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research 6120 S. Vermont Avenue Los Angeles, California 90044 Phone: (323) 759-6063 Fax: (323) 759-2252 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.socallib.org © 2000 Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. All rights reserved. Register of the Robert W. Kenny MSS 003 1 Papers, 1823-1975 Register of the Robert W. Kenny Papers, 1823-1975 Collection number: MSS 003 Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research Los Angeles, California Contact Information: Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research 6120 S. Vermont Avenue Los Angeles, California 90044 Phone: (323) 759-6063 Fax: (323) 759-2252 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.socallib.org Processed by: Mary F. Tyler Date Completed: 1984 © 2000 Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Robert W. Kenny Papers, Date (inclusive): 1823-1975 Collection number: MSS 003 Creator: Kenny, Robert Walker, 1901-1978 Extent: 17 document cases 15 cubic feet Repository: Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. Los Angeles, California Language: English. Access The collection is available for research only at the Library's facility in Los Angeles. The Library is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday. Researchers are encouraged to call or email the Library indicating the nature of their research query prior to making a visit. -

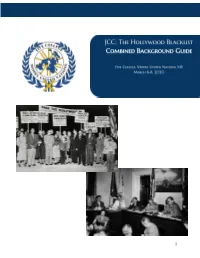

Background Guide for Elaboration on This System and Its History

1 Note from the Crisis Director Hello delegates! My name is Amelia Benich and I’ll be your CD for FCMUN. I am ecstatic to finally get to run this JCC and I hope you are as excited as I am. This is my final FCMUN as I graduate in May and I am determined to make it the best crisis committee to ever be run...or close. I have done Model UN every year I have been in college and have been in so many crisis committees as a delegate I recently had to be reminded of all of them. With this experience both as a delegate and having run 3 committees before both at FCMUN and abroad at LSE’s conference, I can assure you I’ve seen it all and am preparing to stop the common committee frustrations before they begin. As you prepare for the conference, I want you to be fully aware of the parameters of our note system before you plan out a crisis arc. Electronic notes will speed things up, however for this committee to keep things running smoothly, there will be an approximate word limit for notes. Try to keep all notes around 250 words or less (about two paragraphs/a page double spaced), and expect each committee session to get approximately 3 notes answered, meaning your crisis arc should be accomplished in 12-15 notes, assuming notes get shorter and more direct towards the end. Of course, I will do my best to answer faster and get more notes through, but this is to help you both plan effectively and also stay engaged in-room as well. -

Eson Passport Fight — Mrs

FAME Tos = Half Million Strong — Vee k Paul Rob eson Passport Fight — Mrs. Sampson and State Dept. Sit Out Vote as 3,000 Cheer On May 16, Senior Bishop William J. Walls took the microphone at a session of the 34th quadrennial conference of the AME Zion church and said to the assembled Vol. II—No. 6 “JUNE, 1952 Ge *"° 10c audience of 3,000 delegates and visitors: “We are not judges here, but we can demand fair play for all. Everyone here who is in favor of having Mr. Robeson’s passport returned to him—Stand up on your feet!” Three thousand people stood ab once. Only two persons in exciting evening of the drama- leader of the church, castigat- the entire church | remained packed two week session. Mrs. ing the fugitive slave act. He seated: Mrs, Edith Sampson, - Sampson read. a prepared read Frederick Douglass’s fa- U.S. State Department spokes- speech describing the interest- mous admonition on the phil- man, and Mrs. Ruth Whitehead of Europeans in the Negro osophy . of | reform—‘Where Whaley, Secretary to the Board question .and what she had there is no. struggle there is no of Estimate of New York City. told them of the progress made progress’—and the audience That action brought to Mr. by Negroes in the past decade. joined him in singing songs be- Robeson’s suppport in the fight As a. State Department rep- loved in the. Chureh and by the to restore his right to travel resentative, she called for sup- Negro people. abroad, the backing of the third port of U.S.