THE MUSIC PRODUCER AS CREATIVE AGENT Studio Production, Technology and Cultural Space in the Work of Three Finnish Producers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JES High Glow Bio V6

HIGH GLOW Some people won't be pinned down. Just when you think you got them comfortably pigeon-holed into one area of your music collection, they spin their creativity on its head and send your iTunes playlists into a frenzy of confusion. Is it EDM? Is it Rock? Is it Emo/Trance/Poptronica? How do you put all of that together and still come up with something that simply blows you away with every note ......... meet JES. This chart topping and award winning New York native has been the voice behind countless Superstar DJ's. Propelling hit songs with Tiesto, Armin Van Buuren, BT, Gabriel & Dresden among many others. JES has topped numerous charts worldwide and has earned two honors on Billboards famed Decade End Charts including the #4 Dance Airplay song of the decade. Now JES will bring the weight of the world to a standstill on March 15th 2010, when she releases her third album HIGH GLOW with Black Hole Recordings and Ultra Records. JES sure knows how to grab your attention. One of her first releases, the now legendary "As The Rush Comes" by Motorcycle, (A testament to both her songwriting and vocal abilities), quickly catapulted her into the global spotlight of the world's dance music scene going to #1 in countless countries and winning her several awards including the International Dance Music Award at the world famous WMC conference. “As The Rush Comes” ended up as the #4 most played dance song of the decade on Billboards 2000-2010 charts. JESʼ first solo album DISCONNECT produced 3 hit singles “Ghost”, “Heaven” and the #1 chart hit "Imagination" -Billboard Dance Airplay wk of 1/19/09 (also posted on both Year End 2009 at #6 and Decade 2000-2010 charts at #46). -

The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music from the Dean

WINTER 2012 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music From the Dean On behalf of the College of Fine and Applied Arts, I want to congratulate the School of Music on a year of outstanding accomplishments and to WINTER 2012 thank the School’s many alumni and friends who Published for alumni and friends of the School of Music at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. have supported its mission. The School of Music is a unit of the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and has been an accredited institutional member of the National While it teaches and interprets the music of the past, the School is committed Association of Schools of Music since 1933. to educating the next generation of artists and scholars; to preserving our artistic heritage; to pursuing knowledge through research, application, and service; and Karl Kramer, Director Joyce Griggs, Associate Director for Academic Affairs to creating artistic expression for the future. The success of its faculty, students, James Gortner, Assistant Director for Operations and Finance J. Michael Holmes, Enrollment Management Director and alumni in performance and scholarship is outstanding. David Allen, Outreach and Public Engagement Director Sally Takada Bernhardsson, Director of Development Ruth Stoltzfus, Coordinator, Music Events The last few years have witnessed uncertain state funding and, this past year, deep budget cuts. The challenges facing the School and College are real, but Tina Happ, Managing Editor Jean Kramer, Copy Editor so is our ability to chart our own course. The School of Music has resolved to Karen Marie Gallant, Student News Editor Contributing Writers: David Allen, Sally Takada Bernhardsson, move forward together, to disregard the things it can’t control, and to succeed Michael Cameron, Tina Happ, B. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

MES-Päätökset AUDIOVISUAALINEN TUOTANTO

MES-päätökset 1/56 AUDIOVISUAALINEN TUOTANTO Alajärvi Miina Lappi-räppiä käsittelevän pitkän dokumenttielokuvan “Lappi Itsenäiseksi Mixtape” 1 000,00 € (työnimi) kehittely ja käsikirjoit Anundi Anna Annabella Anundi - OLD TIMES 200,00 € Boogieman Management Oy Temple Balls 'Thunder from the North' 800,00 € Finn Andersson Film Productions Oy Fan Theories - Love Is What Is Left 300,00 € Finnish Metal Events Oy Tuska Utopia -virtuaalikonserttisarjan jatkaminen 1 500,00 € Folk Extreme Oy Suistamon Sähkö -yhtyeen musiikkivideo 'Up'n Down' 500,00 € Suistamon Sähkö -yhtyeen musiikkivideo 'Kutsu' 1 500,00 € Ginger Vine Management Oceanhoarsen One with the Gun -musiikkivideo 200,00 € Heinonen Ilkka Ilkka Heinonen Trion musiikkivideo 'Narrien kruunajaiset' 300,00 € Hermansson Jani Hellä Hermanni -artistin musiikkivideo 'Olivetti Lettera' 400,00 € Ikurin Turpiini oy Pate Mustajärvi - Älkää jättäkö -musiikkivideo 750,00 € Pate Mustajärvi:Elvis - musiikkivideo 500,00 € Pate Mustajärvi: Jos maailma on pystyssä huomenna 500,00 € Insomniac Oy Poets of the Fall -yhtyeen musiikkivideo Stay Forever 350,00 € Intervisio Oy Maalaispoika 1 000,00 € 15.06.2021 MES-päätökset 2/56 AUDIOVISUAALINEN TUOTANTO Joensuun Popmuusikot ry Rokumentti Rock Film Festival 2021 1 000,00 € Kaiku Entertainment Oy Elastinen - Ollu tääl 500,00 € Ares - Matkoil 300,00 € Kameron Oy Moon Shot - Confessions 2 000,00 € KHY Suomen Musiikki Oy Villa - Pisarat 750,00 € Kilpi Topi Pelimannin penkillä 2 (työnimi) 1 500,00 € Kiviniemi Joel Rosa Costa - Musta 750,00 € Klippel Mirja Mirja Klippelin -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Tary Spirits

Quareia—The Adept Module II—Magical Construction Lesson 7: The Hall of Planetary Spirits by Josephine McCarthy Quareia Welcome Welcome to this lesson of the Quareia curriculum. The Quareia takes a magical apprentice from the beginning of magic to the level of adeptship and beyond. The course has no superfluous text; there is no dressing, no padding—everything is in its place and everything within the course has a good reason to be there. For more information and all course modules please visit www.quareia.com So remember—in order for this course to work, it is wise to work with the lessons in sequence. If you don’t, it won’t work. Yours, Quareia—The Adept Module II—Magical Construction Lesson 7: The Hall of Planetary Spirits Another, and final, layer that we add to the temple is that of the planetary spirits. This brings the influence of the planetary spirits into a closer relationship with the Inner Temple, which focuses the patterns of fate and the tides of influence that the planets have on the temple’s life and work. This enables the Inner Temple adepts to foresee the tides of fate that gather and express out in the world, and to adjust the temple’s work accordingly. Working in such close connection with the planetary spirits and their influences lets our adepts work with the momentum of the streams of fate rather than pushing against them. It also allows the specific qualities of the individual planetary spirits to be worked with, consulted, and brought into action with the work of the temple and individual adepts through the generations. -

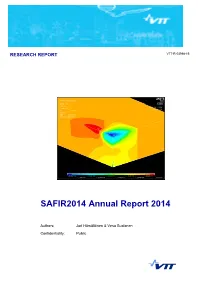

SAFIR2014 Annual Report 2014

RESEARCH REPORT VTT-R-03998-15 SAFIR2014 Annual Report 2014 Authors: Jari Hämäläinen & Vesa Suolanen Confidentiality: Public Preface The mission of the National Nuclear Power Plant Safety Research Programme 2011-2014 (SAFIR2014), derived from the stipulations of the Finnish Nuclear Energy Act, is as follows: The objective of the SAFIR2014 research programme is to develop and maintain experimental research capability, as well as the safety assessment methods and nuclear safety expertise of Finnish nuclear power plants, in order that, should new matters related to nuclear safety arise, their significance can be assessed without delay. The planning period 2011-2014 for the national research programme on nuclear power plant safety involved licensing processes for power plants that are in use or under construction, as well as overall safety evaluations related to licence terms. The construction works of the Olkiluoto 3 plant unit were proceeding, and the construction licence application of Hanhikivi 1 plant unit was to be left for evaluation. These processes are reflected in many ways on national safety research. Research on nuclear safety requires profound training and commitment. The research programme serves as an important environment providing long-term activity that is especially important now when the research community is facing a change of generation. During the planning period and in the following years, many of the experts who have taken part in construction and use of the currently operating plants are retiring. The licensing processes and the possibility of recruiting new personnel for safety-related research projects give an opportunity for experts from different generations to work together, facilitating knowledge transfer to the younger generation. -

Suomalaisen Musiikkiviennin Markkina-Arvo Ja Rakenne 2013-2014

Tunnuslukuja ja tutkimuksia 8 Suomalaisen musiikkiviennin markkina-arvo ja rakenne 2013-2014 Jari Muikku Digital Media Finland Elokuu 2015 K I A I K M I K T Ä – H A A T L S U I A K T I I T S I U E T M Ä A Ä T S S U E S O I M A L A Kirjoittaja FT Jari Muikku on luovien alojen asiantuntija, joka toimii konsulttina Digital Media Finlan- dissa. Hänellä on yli 20 vuoden mittainen kokemus kansainvälisestä musiikkiteollisuudesta, ja hänen toimialaosaamisensa kattaa musiikin lisäksi myös esimerkiksi radion, television sekä internet- ja mobiilipalvelut. Jälkisanat: Music Finland ISSN 2243-0210 Graafinen suunnittelu: L E R O Y Taitto: Music Finland Paino: WhyPrint TUNNUSLUKUJA JA TUTKIMUKSIA 8 Sisällys- luettelo Tiivistelmä ......................................................................................... 4 Johdanto ............................................................................................ 5 Tausta ..................................................................................... 6 Käsitteet ................................................................................. 6 Tutkimusmenetelmä ............................................................... 7 Musiikkiviennin markkina-arvo ........................................................ 9 Elävä musiikki ........................................................................10 Äänitteet .................................................................................11 Tekijänoikeudet ......................................................................11 Muut vientitulot -

Avant Première Catalogue 2017

Avant PreCATALOGUEmi ère 2017 UNITEL is one of the world's leading producers of classical music programmes for film, television, video and new media. Based on exclusive relationships with outstanding artists and institutions like Herbert von Karajan, Leonard Bernstein, the Salzburg Festival and many others, the UNITEL catalogue of more than 1700 titles presents some of the greatest achievements in the last half a century of classical music. Search the complete UNITEL catalogue online at www.unitel.de Front cover: Elīna Garanča in G. Donizetti's “La Favorite” / Photo: Wilfried Hösl UNITEL AVANT PREMIÈRE CATALOGUE 2017 Editorial Team: Konrad von Soden, Franziska Pascher Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: 31st of January 2017 ∙ © Unitel 2017 ∙ All Rights reserved FOR COPRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching / Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas