A Cup of Tea?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multisensory Flavour Perception: Blending, Mixing, Fusion, and Pairing Within and Between the Senses

foods Review Multisensory Flavour Perception: Blending, Mixing, Fusion, and Pairing within and between the Senses Charles Spence Crossmodal Research Laboratory, Oxford University, Oxford OX2 6GG, UK; [email protected] Received: 28 February 2020; Accepted: 21 March 2020; Published: 1 April 2020 Abstract: This review summarizes the various outcomes that may occur when two or more elements are paired in the context of flavour perception. In the first part, I review the literature concerning what happens when flavours, ingredients, and/or culinary techniques are deliberately combined in a dish, drink, or food product. Sometimes the result is fusion but, if one is not careful, the result can equally well be confusion instead. In fact, blending, mixing, fusion, and flavour pairing all provide relevant examples of how the elements in a carefully-crafted multi-element tasting experience may be combined. While the aim is sometimes to obscure the relative contributions of the various elements to the mix (as in the case of blending), at other times, consumers/tasters are explicitly encouraged to contemplate/perceive the nature of the relationship between the contributing elements instead (e.g., as in the case of flavour pairing). There has been a noticeable surge in both popular and commercial interest in fusion foods and flavour pairing in recent years, and various of the ‘rules’ that have been put forward to help explain the successful combination of the elements in such food and/or beverage experiences are discussed. In the second part of the review, I examine the pairing of flavour stimuli with music/soundscapes, in the emerging field of ‘sonic seasoning’. -

The Newsletter

Encouraging knowledge and enhancing the study of Asia iias.asia 80 The Newsletter Tamil film culture and politics The Focus Heritage expertise across Asia Preservation through specific and diverse interventions Chinese tea and Asian societies 2 Contents From the Director In this edition 3 A benevolent crossroads of the Focus 29-40 The Study 5 Representations of the past in a pre- colonial Khmer monastery manuscript Theara Thun 6-7 Empty Home. House ownership in rapidly urbanising China Willy Sier and Sanderien Verstappen 8-9 Southeast Asia and Trump year one: a work in progress Sally Tyler 10-11 Rodrigo Duterte and the Philippine presidency: Rupture or cyclicity? Mesrob Vartavarian The Opinion Heritage 12 Experiences with censorship in research and publication on expertise Singapore’s multiculturalism Lai Ah Eng across Asia The Region 13-15 China Connections Trinidad Rico 16-18 News from Southeast Asia This Focus section proposes to examine and study 19-21 News from Australia and the Pacific cultural heritage debates less on heritage objects 22-25 News from Northeast Asia and practices and more on the human agents that create, promote, and study cultural heritage The Review and its preservation through specific and diverse 26-27 New reviews on newbooks.asia interventions. These interventions do not occur 28 New titles on newbooks.asia in a void: they are often attached to distinct disciplinary approaches and informed by specific political contexts and historical circumstances. The Focus Therefore, the six contributors to this section, 29-30 Introduction: addressing challenging case studies of Heritage expertise across Asia preservation of tangible and intangible heritage Guest editor: Trinidad Rico 31 Palmyra and expert failure in six different regions of Asia, aim to highlight Salam Al Quntar how the involvement of heritage experts affects 32-33 Bordering on the criminal: A clash the very nature of cultural heritage objects and of expertise in Bamyan, Afghanistan practices, including the choice of approaches Constance Wyndham that are used for their study. -

Leaving It All on the Table

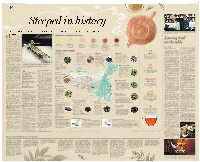

16 CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Tuesday, July 21, 2020 | 17 LIFE Steeped in history The earliest artifacts related to tea in China reveal reciprocal influence between the drink and the civilization, Wang Kaihao reports. Tea-flavored cocktails are the new offerings of Yuanshe Tea Bar in Beijing. JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY istory was rewritten in many respects when the 1,200-year-old underground palace Hwas unearthed at the Famen Bud- Leaving it all dhist Temple in Fufeng county, Shaanxi province, in 1987. Though the bone remains, of which some are thought to be of on the table Buddha, are generally considered to rank among the top archaeolog- ical discoveries in China in the By LI YINGXUE from China Food Information Cen- 20th century, other items found in [email protected] ter, the benefits of tea come from its the 30-square-meter altar of a antioxidants, such as tea polyphe- former Tang Dynasty (618-907) Using peaches from Tangshan, nols, as well as boost provided by royal Buddhist temple are also Hebei province, that were fresh of the caffeine. Additionally, it’s a unmatched. the branch, Chandler Jurinka, 49, good method of consuming water The exquisite silver tea set gilt co-founder of Beijing-based Slow and staying hydrated. with gold — including cages, a con- Boat Brewery, decided to create a He cites research published by tainer with sieves, a grinder, new craft beer. World Cancer Research Fund spoons and other instruments — However, one more ingredient International in 2015, which finds was the beloved possession of was required to perfect the flavor of that there is some evidence to sug- emperor Li Xuan, who reigned the beer, so he chose oolong tea. -

Emperor Huizong

國際茶亭 Global TeaTea Hut& Tao Magazine April 2016 Classics of Tea Emperor Huizong's Treatise on Tea Moonlight White Tea GL BAL TEA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine ContentsIssue 51 / April 2016 Moonlight White This is our second issue in the Classics of Tea series, following the Cha Jing we trans- lated last September. The emperor Huizong’s Love is Treatise on Tea offers a window into Song Dynasty tea, and the lives of some of the ear- changing the world liest Global Tea Hut members. The emperor loved white tea above all else. Moonlight White is a great white tea from the forests of Yunnan. bowl by bowl Features 15 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE EMPEROR 19 THE EMPEROR & THE ART OF TEA By Steven D. Owyoung 29 SONG HUIZONG 15 19 THE ARTIST By Michelle Huang 35 TREATISE ON TEA By Song Huizong 35 Regulars 03 TEA OF THE MONTH “Moonlight White,” White Tea Daqing, Jinggu, Yunnan 11 TEA EXPERIMENTS Song Dynasty-esque Whisked Tea 49 TEAWAYFARER Dalal al Sayer, Kuwait © 2016 by Global Tea Hut All rights reserved. 月 No part of this publication may be re- produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, 光 electronic, mechanical, photocopying, re- cording, or otherwise, without prior writ- 白 ten permission from the copyright owner. From the Editor n April, we move into the heart of spring. Tea buds genres of tea in one book or the many classics we hope are opening to another year’s rain and weather. to translate over the years. -

Tea and Tea Blending, Tea

\-v\u. TEA AND TEA BLENDING, TEA AND TEA BLENDING, A MEMBER OF THE FIRM OF LEWIS & CO. CRUTCHED FRIARS, LONDON. FOURTH EDITION. LONDON : EDEN FISHER & Co., 50, LOMBARD ST., & 96-97, FENCHURCH ST., E.G. 1894. CONTENTS. PAGE INTRODUCTION .. .. .. vi TEA IN ENGLAND .. .. .. .. i HISTORY OF THE TEA TRADE .. .. .-33 THE TEA DUTY . 49 HINTS ON TEA MAKING .. .. .. 52 TEA STATISTICS .. .. .. .. 57 Imports of Tea into England 1610-1841 . 57 Tea Statistics for the Fifty Years 1842-1891 . .. 60 CHINA TEA . 67 Cultivation and Manufacture . 67 Monings . 75 Kaisows . 79 ' New Makes .. .. .. .. ..83 Oolongs and Scented Teas . 86 Green Teas . 90 INDIAN TEA .. .. .. .. .. 95 Tea in India . 95 Cultivation and Manufacture . 99 Indian Tea Districts .. .. .. ..no CEYLON TEA .. .. .. .. .. 120 JAPAN AND JAVA TEAS, ETC. .. .. ..126 TEA BLENDING .. .. .. .. .. 131 SPECIMEN BLENDS .. .. .. 143 SUMMARY AND CONCLUDING HINTS.. .. 149 INTRODUCTION. THE present volume is intended to give all those engaged in the Tea Trade, who wish to take an intelligent interest in it, a sketch of its growth and development in this country and a comprehensive review of its present and to a mass scope position ; bring together of hitherto inaccessible facts and details of practical importance to the Trade, and to give such instructions, hints and advice, on the subject of blending, as shall enable every reader to attain with facility a degree of proficiency in the art which previously could only be arrived at by a course of long and often costly experience. No pains have been spared in the collection of materials, the best authorities having been consulted with regard to all matters on which the author cannot speak from personal experience, and all information is brought down to the latest moment. -

An Exploration Into the Elegant Tastes of Chinese Tea Culture

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 5, No. 2; 2013 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education An Exploration into the Elegant Tastes of Chinese Tea Culture Hongliang Du1 1 Foreign Language Department, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, China Correspondence: Hongliang Du, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, 5 Dongfeng Road, Jinshui District, Zhengzhou 450002, China. Tel: 86-138-380-659-16. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 13, 2013 Accepted: February 19, 2013 Online Published: March 8, 2013 doi:10.5539/ach.v5n2p44 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v5n2p44 This research is funded by Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (11YJA751011). Abstract China was the first to produce tea and consumed the largest quantities and its craftsmanship was the finest. During the development of Chinese history, Chinese Tea culture came into being. In ancient China, drinking tea is not only a very common phenomenon but also an elegant taste for men of letters and officials. Chinese tea culture is extensive and profound and it is necessary for foreigners to understand Chinese tea culture for the purpose of smooth and deepen the communication with the Chinese people. Keywords: tea culture, elegant taste, cultural communication 1. Introduction Chinese tea culture is a unique phenomenon about the production and drinking of tea. There is an old Chinese saying which goes, “daily necessaries are fuel, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce, vinegar and tea” (Zhu, 1984: 106). Drinking tea was very common in ancient China. Chinese tea culture is of a long history, profound and extensive. -

Master Xie Yuan Zai (謝元在)

of the ver the course of this issue, ous reasons are the thick, juicy leaves to a particular terroir. Farmers were we are going to explore diet, of this varietal, as well as its strong and learning, honing their skills through 茶 food and some of the Cen- powerful flavor and aroma, and the some trial and error, as well as a deep Oter’s food philosophy as well as recipes. patience of this tea—one of the lon- connection to a life of tea, trying to To accompany such a culinary explo- gest-lasting teas there are. The vibrancy process their local varietals in a way that ration, we need a delicious tea—one of the tree, the processed leaves and the would highlight their greatest qualities that excites us in fragrance and aroma, liquor suit the name, in other words. and fulfill the tea’s potential. It would bringing delicious cups to the table The first waves of immigration not be correct to say that oolong, for along with all the food we’re going from the Mainland to Taiwan were example, is just a method of processing to be cooking. For that, we decided from Fujian, and the colonists quickly tea, because that processing was ad- on one of our favorite types of tea, recognized that Taiwan had the per- vanced to suit certain varietals of tea. Tieguanyin. fect terroir for tea production. They And as varietals have changed, moving Tieguanyin originally comes from began bringing seeds over to start tea from place to place (whether natural- Anxi, in southern Fujian. -

The Impact of Tea in Song Dynasty China

The Impact of Tea in Song Dynasty China Brett Harris Submitted to the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures of the University of Florida in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Dr. Richard Wang, Honors Thesis Advisor Abstract This thesis is a study on the impact that tea played in Song Dynasty China, 960-1276 A.D. Tea reached a vogue that was unmatched at the time, and it impacted the culture of the time in many different ways. Additionally, tea played a huge role in the Song economy. In a time of almost perpetual warfare, the Chinese needed a way to procure horses. Through the Tea and Horse Agency, the Song Dynasty government was able to trade tea for the extremely valuable warhorses. Without horses, the Chinese had no chance against the powerful, highly organized steppe empires of the time. Tea was the major commodity traded to obtain the requisite horses used to keep peace for over three hundred years. 1 Tea’s Impact in Song Dynasty China Tea in China dates back to at least the Han Dynasty. The earliest written records of tea drinking come from “A Contract with a Child Servant” by Wang Bao in the year 59 B.C. (Wang 2). While originally popular mostly among the southern Chinese, tea drinking spread throughout the country. This permeation through China took place mainly during the eighth century. The eighth century saw Lu Yu’s “Book of Tea,” and many poets composed poems to the drink. An eighth century tea aficionado named Feng Yan also attributes its prevalence to Buddhism. -

Tea, Its Mystery and History

TEA MYSTERY AND HISTOff ILLUSTRATED. m LO FONG LOH, C.LC.S SECRETARY TO THE CHINESE EDUCATIONAL MISSION, IN EUROPE, o z UJ u < z z CC O tl CO Q: I O O Li- o S TEA ITS MYSTERY AND HISTORY. TEA ITS MYSTERY AND HISTORY BY SAMUEL PHILLIPS DAY, Author of "Food Papers : a Popular Treatise on Dietetics "etc. WITH A PEEFACE IN CHINESE AND ENGLISH BY LO FONG LOH, C.I.C.S., Secretary to the Chinese Educational Mission in Europe. ILLUSTRATED. " The Sovereign drink of Pleasure and of Health." BRADY. LONDON: SIMPKIN, MARSHALL & CO., STATIONERS' HALL COURT. 1878. Price Onfi Shilling. TO THE LOVERS OF PURE TEA, THIS TREATISE IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. CONTENTS. PREFACE IN CHINESE. NOTES ON THE CHINESE LANGUAGE EXTRACT FROM MR. Lo FONG LOH'S JOURNAL CHAPTER I. LEGENDARY ORIGIN OF THE PLANT 17 CHAPTER II. INTRODUCTION OF TEA INTO ENGLAND 27 CHAPTER III. APPRECIATION OF THE LEAF 36 CHAPTER IV. THE PLANT BOTANICALLY CONSIDERED ... CHAPTER V. HISTORY OF THE TEA TRADE 48 CONTENTS. CHAPTER VI THE COLOURING OF THE LEAF ... f>7 CHAPTER VII. SOCIAL CHARACTER OF THE BEVERAGE f>0 CHAPTER VIIL THE "DRINK OF HEALTH" 70 CHAPTER IX. THE VIRTUES OF THE LEAF 78 CHAPTER X. A CUP OF TEA DO NOTES ON THE CHINESE LANGUAGE. HE Chinese writing is eminently pic- as the admits turesque ; and language of no alphabet, all ideas and objects are conveyed through the medium of groups of characters, each group representing a series of impressions, or opinions. By an ingenious and elaborate combination of strokes, upwards of 40,000 distinct symbols are perfected. -

More Than Just a Drink: Tea Consumption, Material Culture, and 'Sensory Turn' in Early Modern China (1550-1700) a DISSERTATI

More than just a Drink: Tea Consumption, Material Culture, and ‘Sensory Turn’ in Early Modern China (1550-1700) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Yuanxin Jiang IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ann Waltner December 2019 © Yuanxin Jiang 2019 Table of Contents List of Figures ii List of Maps iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Rise and Fall of Luojie Tea: Materiality, “Sensory 31 Turn,” and Gender Relations in Late-Ming Tea Literature Chapter 2 Songluo and Longjing: New Taste, New Method, and New 83 Market Chapter 3 The Taste of Tastelessness: Water Tasting, Tea Drinking, 122 and Social Status in Late-Ming China Chapter 4 An Elegant Object in a Studio: Scholar-officials’ Taste and 172 the Development of Yixing Teapots in the Seventeenth Century Chapter 5 Consuming Space in Late-Ming China: The Pleasures of 227 the Teahouse and the Joys of Exclusiveness Conclusion 270 Bibliography 272 Glossary 283 i List of Figures Figure 1.1 Songxi lun hua tu zhou by Qiu Ying 57 Figure 1.2 Yi lan xiao jing by Wen Zhengming 58 Figure 2.1 The Location of the Dragon Well and West Lake 119 Figure 3.1 Huishan cha hui tu juan by Wen Zhengming 165 Figure 4.1. Tea wares found in Famen Monastery 176 Figure 4.2 Ming yuan du shi tu attributed to Liu Songnian 181 Figure 4.3 A teapot with an inscription of Dabin on the bottom 207 Figure 5.1 An excerpt from Qingming shang he tu 247 ii List of Maps Map 1.1 The Production Area of Luojie Tea 36 Map 2.1 Huizhou in the Late Imperial Yangzi River -

Special Extended Edition 國際茶亭

Global 國際茶亭Tea Hut Tea & Tao Magazine September 2016 Special Extended Edition Taiwanese Oolong Tea History, processing & Lore GL BAL TEA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine ContentsIssue 56 / September 2016 Nostalgia It is that special time of year again: time for the extended special edition of our maga- zine, with lots of extra pages to explore a tea Love is topic in greater depth! This year, we’re staying home, touring the island of Taiwan to learn more about Taiwanese oolong tea, sipping changing the world cups of Nostalgia along the way—one of the best teas we’ve ever shared! bowl by bowl Features 17 INTRODUCTION Special thanks to Li Guang Chung 27 HOW OOLONG GOT ITS NAME 29 29 VARIETALS OF TAIWANESE OOLONG 43 THE LOST ART OF OOLONG Interview with He Jian 49 A HISTORY OF TAIWANESE OOLONG By Ruan Yi Ming 57 73 57 ORGANIC OOLONGS OF THE NORTH 73 TRADITIONAL OOLONG NOWADAYS Interview with Lu Li Zhen Regulars 03 TEA OF THE MONTH “Nostalgia,” 2016 Traditional Oolong, Li Shan, Taiwan 37 GONGFU EXPERIMENTS 43 Outside the Boundaries 77 TEAWAYFARER © 2016 by Global Tea Hut Caitlin Mercado, USA All rights reserved. 懷 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored 舊 in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by 之 any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, re- cording, or otherwise, without prior written permis- 情 sion from the copyright owner. From the Editor n September, the weather in Taiwan turns to tea. Traveling further into any tea region, history or topic It cools down and the oppressive heat of the sum- exposes just how vast, rich and varied the tea world is. -

The Influence of Teacup Shape on the Cognitive Perception of Tea, and the Sustainability Value of the Aesthetic and Practical De

sustainability Article The Influence of Teacup Shape on the Cognitive Perception of Tea, and the Sustainability Value of the Aesthetic and Practical Design of a Teacup Su-Chiu Yang 1,2, Li-Hsun Peng 3,* and Li-Chieh Hsu 2 1 Graduate School of Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin 64002, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 School of Arts and Design, Sanming University, Sanming 365004, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Creative Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin 64002, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 September 2019; Accepted: 21 November 2019; Published: 4 December 2019 Abstract: The ceramic industry is among the most profitable industries in the world, but, because of the use of nonrenewable materials and high fuel consumption, it also has a carbon footprint. Ceramic materials account for the majority of drinking vessels. Several scholars found that consumers’ awareness of drinks and purchasing desires are highly correlated with a vessel’s shape and color—in other words, the visual stimulation. However, since prior studies have focused on alcohol, bubble drinks, juice, coffee, cocoa, etc., there has rarely been any research on the appropriate drinking vessels for Chinese tea. This study intends to investigate the visual design of vessels for Chinese tea, in terms of its impact on the taste of the drink, by integrating the thinking and methods of expert users and designers for the sustainability of design and industry. In this study, tea experts and designers were asked for their opinions as a means of data collection.