Concepts and Teaching Workshop, and Helpful Hints and Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams -

Dallas (1978 TV Series)

Dallas (1978 TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the original 1978–1991 television series. For the sequel, see Dallas (2012 TV series). Dallas is a long-running American prime time television soap opera that aired from April 2, 1978, to May 3, 1991, on CBS. The series revolves around a wealthy and feuding Texan family, the Ewings, who own the independent oil company Ewing Oil and the cattle-ranching land of Southfork. The series originally focused on the marriage of Bobby Ewing and Pamela Barnes, whose families were sworn enemies with each other. As the series progressed, oil tycoon J.R. Ewing grew to be the show's main character, whose schemes and dirty business became the show's trademark.[1] When the show ended in May 1991, J.R. was the only character to have appeared in every episode. The show was famous for its cliffhangers, including the Who shot J.R.? mystery. The 1980 episode Who Done It remains the second highest rated prime-time telecast ever.[2] The show also featured a "Dream Season", in which the entirety of the ninth season was revealed to have been a dream of Pam Ewing's. After 14 seasons, the series finale "Conundrum" aired in 1991. The show had a relatively ensemble cast. Larry Hagman stars as greedy, scheming oil tycoon J.R. Ewing, stage/screen actressBarbara Bel Geddes as family matriarch Miss Ellie and movie Western actor Jim Davis as Ewing patriarch Jock, his last role before his death in 1981. The series won four Emmy Awards, including a 1980 Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series win for Bel Geddes. -

Reminder Calendar (FOR CHAPTER OFFICERS, ALUMNJE ADVISERS, and PROVINCE PRESIDENTS) Continued on Cover Ill

Reminder Calendar (FOR CHAPTER OFFICERS, ALUMNJE ADVISERS, AND PROVINCE PRESIDENTS) Continued on Cover ill August 25-KEY correspondent places chapter news letter for October KEY in mail to editor's deputy (See opposite page for name and address) Blue KEY stationery is supplied by central office. October 7-Treasurer places monthly finance report in mail to national accountant and province president. October 7-Aiumna finance adviser places monthly report in mail to national finance chairman. October 10-Treasurer sends chapter's subscription ($2) for Banta's Greek lila:change to the executive secretary, October 13-FOUNDERS' DAY, Wear Kappa colors. October 15-Treasurer sends copy of corrected budget to national accountant, national finance chairman, and province president, October 25-KEY correspondent places chapter news letter for December KEY in mail to editor's deputy. October 30-Registrar sends to executive secretary typewritten lists as follows : names and college ad dresses of all active members; changes of addresses of last semester seniors, transfers, and other initiated girls leaving school since February report for KEY mailing list; list of con1licts with other fraternities. November 1-Treasurer mails return postal to national finance chairman stating that letters and charge sheets have been mailed to all parents of active and pledge members. November 7-Treasurer places monthly finance report in mail to national accountant and province president. November 7-Aiumna finance adviser places monthly report in mail to national finance chairman. November 15-Chairman of alumnm advisory board sends province president a report of monthly board meetings. November 15-Registrar sends to grand registrar annual report of archives. -

Southwest Texas Program 2009

Reeling in the Years 30 Years of Film, TV and Popular Culture Southwest/Texas Popular Culture and American Culture Association Hyatt Regency Albuquerque, New Mexico February 25 – 28, 2009 www.swtxpca.org “ Reeling in the Years “ Southwest Texas 30 Years of Culture of Film, TV and Popular Culture Table of Contents Panels 100‐106 .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1:00 p.m. – 2:30 p.m. Wednesday, February 25, 2009 ............................................................................... 1 100 Creative Writing I ............................................................................................................................... 1 101 Media and Globalization I .................................................................................................................. 1 102 Graphic Novels, Comics, and Popular Culture I ................................................................................. 2 103 Computer Culture I ............................................................................................................................ 2 104 Grateful Dead I ................................................................................................................................... 2 105 American Indians Today I ................................................................................................................... 3 106 Science Fiction and Fantasy I ............................................................................................................ -

Students with ACC Concert

SMC security - page 3 ......--. .r VOL XX, NO. l 7 till" IIH.kpnH.Icnl .,lulknt Ill"" ... p;11wr .,,,:n mg notn dame ;md .,aint man·., nJESDAY, SEPTEMBER I 7, 198~ Senate makes plan to 'sting' students j with ACC concert I By CHRIS BEDNARSKI "There's liable to be a lot of things Senior Staff Reporter that come up that we don't know how to handle. It will be a big bonus The Student Senate approved a to have a professional around," said J resolution last night that could bring Jim Hagan, off-campus senator. rock performer Sting to the Athletic "I think Sting is a bigger draw than and Convocation Center on Novem Tina Turner," said Howard. "Let's ber7. sell out and make a profit for a "It's an opportunity to bring a change," he said. major entertainer to campus," said The Turner concert did not sell Lee Broussard, Student Activities out, but instead sold approximately Board manager. 7,000 tickets in her ACC appearance Sting charges an appearance fee of onSept. 1. S40,000 plus 60 percent of the con Reminding the senate that the Stu cert's profits, said Ron Mileti, the dent Activities Board is not in the i\ Student Activites musical entertain· business of making money, Badin ment commissioner. Hall President Judith Windhorst, ... · \ - I There would be an additional said "We shouldn't have to worry \~ charge of approximately S27,000 in about splitting our profits. production costs, and 1 5 percent of "If we have to split profits with The Obeervn/Paul Pahoresky the gross revenues from the concert someone I will be happy to. -

Dallas (1978 TV Series) Ç”Μ影Ƽ”Å‘˜ ĸ²È¡Œ (Cast)

Dallas (1978 TV series) 电影演员 串行 (Cast) Steve Kanaly https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/steve-kanaly-471957/movies William Boyett https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/william-boyett-595638/movies Casey Sander https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/casey-sander-2940994/movies Parley Baer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/parley-baer-973490/movies William Bassett https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/william-bassett-16096817/movies Frank Marth https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/frank-marth-3082704/movies Jack Collins https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/jack-collins-3805565/movies è‘›è˜Â ·å¯‡çˆ¾è²ç ‰¹ https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/%E8%91%9B%E8%98%AD%C2%B7%E5%AF%87%E7%88%BE%E8%B2%9D%E7%89%B9-478443/movies çº¦ç¿°Â·éº¦å…‹è¿žæ© https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/%E7%BA%A6%E7%BF%B0%C2%B7%E9%BA%A6%E5%85%8B%E8%BF%9E%E6%81%A9-3182067/movies Jack Scalia https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/jack-scalia-1386159/movies Karen Carlson https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/karen-carlson-3812964/movies Michael C. Gwynne https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/michael-c.-gwynne-3308078/movies Cliff Potts https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/cliff-potts-346245/movies è˜æ –¯Â·è“‹æ–¯ç‰¹ https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/%E8%98%AD%E6%96%AF%C2%B7%E8%93%8B%E6%96%AF%E7%89%B9-3216928/movies Harry Carey https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/harry-carey-1397312/movies George Coe https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/george-coe-3760469/movies 喬治·DÂ·è¯ èŠ -

Remington Steele Episo De Guide

Remington Steele Episo de Guide Version Compiled by Raymond Chen Revision history Version Septemb er Version Version Version Version x February internal Version Decemb er c Copyright Raymond Chen all rights reserved Permission is granted to copy and repro duce this do cument provided that it b e distributed in its entirety including this page No charge may b e made for this do cument b eyond the costs of printing and distribution No mo dications may b e made to this do cument Preface This episo de guide b egan as a collection of private notes on the program Remington Steele which I had kept while watching the show on NBC in the eighties Yes I take notes on most television programs I watch Call me analretentive Sometime in early I got the crazy idea of creating an episo de guide and the rst edition of this guide eventually app eared later that year Still not satised and unable to recall the plots of most of the episo des b eyond the sketchiest of descriptions I decided to give my feeble brain cells a breather and write out more detailed plot summaries as I watched the episo des I consider using a VCR to b e cheating and b esides you can read a plot summary faster than you can watch a tap e There you have it the confessions of a neurotic televisionwatcher Not in the printed guide but available in the guide source is a summary of musical themes and a list of quotes Remington Steele still gets my vote for the show with the b est incidental music No other show I know comes even close The quotes you can add to your favorite -

Ihaurliratrr Hrralft Oolira Muot Bo Orosontod to Staining Done

W Ma n c h e s t e r h e r a l d , Thursday. July 30. 1M7 rUBUC HMmiM Piojyin. com. FOR RENT CAM ICAM FM8ALE Iforsale a Sm m F )* ROOMS, Mala or FOmala. Cancen Reagan pays price for sun / page Contratly locattd. Klt- PONTIAC SunMrd 1978.6 CHEVY 1979. Excellent N L E a st Mets sweep g ? * jyo lin f comnMiito chon prlvllodflot. Reas cylinder, sunroof, new ggg* Wibdivltlon tlrea. Many good porta. onable. Apply at 39 brakes, tires end 8190. Coll after 5:30. SSSnSSSLay MeCorrlton- Cottape Street, be- e S t t A - J " ’* "Tinicnr clutch. 8750 or best 643-9997. Cards’ series to tighten t 22?. $!**vlslen. SMtIor tween 9-4.____________ offer. 643-6370 or 74^ i a s i r “ £h r y Al 6 r £ o rd o b i sailor FE M A LE preferred, klt- — J < ^ N tv Chid care? 7667. 7om-2:30pm. W r ^ M omitoln Hood / VUI'- Ooes It eeem you never ALLphasSofVBr3w 1976. Good condition, cross Atlantic / page the race / page 20 chen prlvllepes, bus Coli' NoimlBt “ R " Us MEDICAL Tr« F i r e b i r d Fi , V-6 power dependable car. 8450. line. Evenings and hove tlmetoenloy itfet Very reosonoblet Jim 2SL22!"*. wf'wy «*«♦ rood lne.< Qt 233-7457. Ask for Let me relieve you of tionist win steering, brakes, air. 643-2929 after 5:30. - SJJKJJji"**_W®*lonbory, weekends only 647- SuionnB. 6494M77. time o f v< .««■ wouM contain lota. household chores a i^ Mint condition. S3300. -

Annual Report 2019 Justice in Every Borough

Annual Report 2019 Justice in Every Borough Leading through partnership, expertise where it matters The Legal Aid Society Employees Daniel Abdul-Malak, Charlene Abney, Hope Acevedo, Joshua Ackerman, Benjie Acunis, Alexander Adami, Lindsay Adams, Vanessa Adegbite, Melissa Ader, Katherine Adler, David Affler, Gabriella Agranat- Getz, Alena Aguilar, Jacqueline Ahearn, Noor Ahmad, Mastaque Ahmed, Hira Ahmed, Hatire Aikebaier, Diane Akerman, Akintunde Akinjiola, Sukayna Al-Aaraji, Shivani Alamo, Michael Alcarese, Myra Alcarese, Jean Alexandre, Gary Alexion, Ronald Alfano, Marianne Allegro, Melinda Allen, Chevelle Allison-McIntosh, Rebekah Almanzar, Jodi Almengor, Steve Alonso, Juan Alonzo, Michelle Altamirano, Charles Alvarez, Carla Alvarez-Gould, Lizet Amado, Katherine Amaya, Chelsey Amelkin, Nana Ama Amoah-Kusi, Akeem Amodu, Sara Amri, Anyamobi Ananaba, Sarah Anderson, Sharon Anderson, Tareek Anderson, Melinda Andra, Cheryl Andrada, Kaitlin Andrews, Nefertiti Ankra, Carmine Annunziato, Bahar Ansari, Kenneth Ansley, Alexandra Anthony, Odessa Antoine, Ikenna Anyoku, Nana Aoki, Anastasia Apostoleris, Ruth Appadoo-Johnson, Israel Appel, Rigodis Appling, Marienil Aquino, Haifa Arab, Noha Arafa, Rumzi Araj, Violeta Arciniega, Juan Ardila, Martha Arellano, Rebecca Arian, Jimmy Arias, Vivian Arismendiz Arevalo, Tarini Arogyaswamy, Marisol Arriaga, Jessica Arroyo, William Artus, Sherry Ashkins, Daniel Ashworth, Richard Asphall, Nicole Attara, Edward Auffant, Lynda Augente, Quincy Auger, Germaine Auguste, Garrett Austin, Elenor Austrie, Jesse Aviles, -

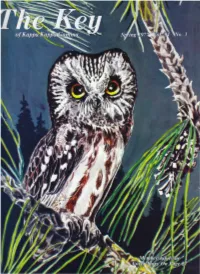

THE KEY VOL 94 NO 1 SPRING 1977.Pdf

The Key of Kappa Kappa Gamma EDUCATIONAL JOURNAL Vol. 94, No. 1, Spring 1977 The .first college wo men 's magazine. Published continuously Stnce 1882 Fraternity Headquarters, 530 East Town St., Columbus, OH 43215. (Mailing address : P.O. Box 2079, Columbus, OH 43216) Send all editorial material and corre spondence to the: EDITOR-Mrs. David B. Selby, 6750 Merwin Place, Worthington, OH 43085 Send all active chapter news and pictures to: Alums greeting Sandy Hartman, rushee and new pledge of ET ACTIVE CHAPTER EDITOR-Mrs. Willis C. Mississippi State. Left to right: Carrie Evans, ET Membership Pflugh, Jr., 2359 Juan St., San Diego, CA Adviser; Betty Jane Gary, 6P -Mississippi Membership Adviser; 92103 Kay McMahon, ET Personnel Adviser; and Ellen Weatherly, ET Send all alumnae news and pictures to: Chapter Council adviser. ALUMNAE EDITOR-Mrs. Robert Whittaker, 683 Vance Av ., Wyckoff, NJ 07481 Send all business items and change of address, six weeks prior to month of publica Building Kappas- tion to FRATERNITY HEADQUARTERS-P.O. Box In intramural competition, KKC 2079, Columbus, OH 43216. (Duplicate Active Viewpoint were football champs and took trophi copies cannot be sent to replace those in volleyball and softball. undelivered through failure to send advance notice.) Second class postage paid at Co Kappa is a kaleidoscope of many per The Kappa Fraternity philanthropy lumbus, OH and at additional mailing offices. sonalities opening a door to friendship rehabilitation. Here in Columbia, t Copyright, Kappa Kappa Gamma Fraternity and sisterhood. In Kappa, a girl will get Rusk Rehab Center is our special pre 1977. Price $1 .50 single copy. -

The Chronicle Friday, October 9, 1987 « Duke University Durham, North Carolina Circulation: 15,000 Vol

THE CHRONICLE FRIDAY, OCTOBER 9, 1987 « DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 83. NO. 31 University administrator dies Community, University leader described as 'selfless' From staff reports said Edward Hill, director of the Mary Richard Whitted, highly regarded Uni Lou Williams Center and a close friend of versity administrator, community servant Whitted. "He was the kind of person that and counselor to students, died early makes our job stimulating and interest Thursday morning of cancer. He was 43. ing. "He was important to me and my asso "He had an unusual selflessness, giving ciates because of his thought processes," of himself, especially to students. He had said William Griffith, vice president for a tremendous respect for students and student affairs. "He had a political in their ideas. stinct in the best sense ofthe word." He "He learned a great deal about himself was a "special person" who had a unique from his association from these young ability "to coalesce people to resolve diffi people," Hill said. cult problems and tasks. Whitted came to the University in 1971. Whitted served most recently as as A native of Hillsborough, he graduated sistant to the vice president for student from North Carolina Central University affairs. in 1968. Before he became assistant to "He was a good listener, yet he was not Griffith in 1982, Whitted served the Uni reluctant to give his own reasoned versity as supervisor of general accoun advice," Griffith said. ting, cost accounting specialist for the in As Griffith's assistant, Whitted worked surance department and community rela on a number of projects. -

2019-2020 Board of Trustees Installation Service and Dinner

6930 Alpha Road / Dallas, Texas 75240-3602 / 972-661-1810 / FAX 972-661-2636 E-mail: [email protected] / Facebook: Temple Shalom Dallas / Website: www.templeshalomdallas.org MAY 2019 NISAN & IYAR 5779 VOLUME 53 NO. 10 2019-2020 Board of Trustees Installation Service and Dinner Open to the Entire Congregation Friday, May 24, 2019 6:00pm - Wine & Cheese Reception 6:30pm - Shabbat Service, Installation, and Guest Speaker Congressperson Colin Allred 7:45pm - Optional Shabbat Dinner (register by Friday, May 17 at 5:00pm) $25 per person Enjoy a catered Shabbat dinner of Homemade challah made by Julie Gadsby Pecan Crusted Chicken or Vegetarian meal provided by Lush Catering Background music by our very own Slava Kutman Planning Committee Michelle Falk Julie Gadsby Kim Kort Lisa Rosenfeld Cristie Schlosser Babysitting reservations by May 17 to Michelle Falk at [email protected] Questions? Email Cristie Schlosser at [email protected] Be sure to indicate the number in your party when you make your reservation. Payment must accompany your reservation. You may pay on our website by clicking here. You may also contact Deena at 972-661-1810 ext. 203 with a credit card number, or make your reservation in the Temple Administration Office with a check or cash. SHABBAT SERVICES FRIDAY ~ May 3 SATURDAY ~ May 18 Acharei Mot ~ Leviticus 16: 1-34 10:30am - Morning Minyan 6:30pm - Confirmation Service Epstein Chapel Sanctuary FRIDAY ~ May 24 SATURDAY ~ May 4 B’har ~ Leviticus 25:1-28 8:00am - Music, Meditation, Movement Shabbat 6:30pm -