Phonology and Syntax: a Shifting Relationship Ricardo Bermu´Dez-Oteroa,*, Patrick Honeyboneb,1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Is Language Typology Possible?

Why is language typology possible? Martin Haspelmath 1 Languages are incomparable Each language has its own system. Each language has its own categories. Each language is a world of its own. 2 Or are all languages like Latin? nominative the book genitive of the book dative to the book accusative the book ablative from the book 3 Or are all languages like English? 4 How could languages be compared? If languages are so different: What could be possible tertia comparationis (= entities that are identical across comparanda and thus permit comparison)? 5 Three approaches • Indeed, language typology is impossible (non- aprioristic structuralism) • Typology is possible based on cross-linguistic categories (aprioristic generativism) • Typology is possible without cross-linguistic categories (non-aprioristic typology) 6 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Franz Boas (1858-1942) The categories chosen for description in the Handbook “depend entirely on the inner form of each language...” Boas, Franz. 1911. Introduction to The Handbook of American Indian Languages. 7 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) “dans la langue il n’y a que des différences...” (In a language there are only differences) i.e. all categories are determined by the ways in which they differ from other categories, and each language has different ways of cutting up the sound space and the meaning space de Saussure, Ferdinand. 1915. Cours de linguistique générale. 8 Example: Datives across languages cf. Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. The geometry of grammatical meaning: semantic maps and cross-linguistic comparison 9 Example: Datives across languages 10 Example: Datives across languages 11 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Peter H. Matthews (University of Cambridge) Matthews 1997:199: "To ask whether a language 'has' some category is...to ask a fairly sophisticated question.. -

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

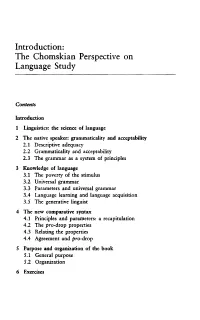

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

1 Meeting of the Committee of Editors of Linguistics Journals January 10

Meeting of the Committee of Editors of Linguistics Journals January 10, 2016 Washington, DC Present: Eric Baković, Greg Carlson, Abby Cohn, Elizabeth Cowper, Kai von Fintel, Brian Joseph, Tom Purnell, Johan Rooryck (via Skype) 1. Unified Stylesheet v2.0 Kai von Fintel discussed his involvement in a working group aiming to “update, revise, amend, precisify” the existing Unified Stylesheet for Linguistics Journals. An email from von Fintel on this topic sent to the editors’ mailing list shortly after our meeting is copied at the end of these minutes. Abby Cohn noted that Laboratory Phonology will continue to use APA style given its close contact with relevant fields that use also this style. It was also noted and agreed that authors should be encouraged to ensure the stability of online works for citation purposes. 2. LingOA Johan Rooryck reported on the very recent transition of subscription Lingua (Elsevier) to open access Glossa (Ubiquity Press), and addressed questions about a document he sent to the editors’ mailing list in November (also appended at the end of these minutes). The document invites the editorial teams of other subscription journals in linguistics and related fields to make the move to fair open access, as defined by LingOA (http://lingoa.eu), to join Glossa as well as Laboratory Phonology and Journal of Portuguese Linguistics. On January 9, David Barner (Psychology & Linguistics, UC San Diego) and Jesse Snedeker (Psychology, Harvard) called for fair open access at Cognition, another Elsevier journal. (See http://meaningseeds.com/2016/01/09/fair- open-access-at-cognition/.) The transition of Lingua to Glossa has apparently gone even smoother than expected. -

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: a Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, Thierry Poibeau, Ekaterina Shutova, Anna Korhonen To cite this version: Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, et al.. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing. 2018. hal-01856176 HAL Id: hal-01856176 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01856176 Preprint submitted on 9 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Maria Ponti∗ Helen O’Horan∗∗ LTL, University of Cambridge LTL, University of Cambridge Yevgeni Berzaky Ivan Vuli´cz Department of Brain and Cognitive LTL, University of Cambridge Sciences, MIT Roi Reichart§ Thierry Poibeau# Faculty of Industrial Engineering and LATTICE Lab, CNRS and ENS/PSL and Management, Technion - IIT Univ. Sorbonne nouvelle/USPC Ekaterina Shutova** Anna Korhonenyy ILLC, University of Amsterdam LTL, University of Cambridge Understanding cross-lingual variation is essential for the development of effective multilingual natural language processing (NLP) applications. -

Multi-Disciplinary Lexicography

Multi-disciplinary Lexicography Multi-disciplinary Lexicography: Traditions and Challenges of the XXIst Century Edited by Olga M. Karpova and Faina I. Kartashkova Multi-disciplinary Lexicography: Traditions and Challenges of the XXIst Century, Edited by Olga M. Karpova and Faina I. Kartashkova This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Olga M. Karpova and Faina I. Kartashkova and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4256-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4256-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix List of Tables............................................................................................... x Editors’ Preface .......................................................................................... xi Olga M. Karpova and Faina I. Kartashkova Ivanovo Lexicographic School................................................................ xvii Ekaterina A. Shilova Part I: Dictionary as a Cross-road of Language and Culture Chapter One................................................................................................ -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

A New State-Of-The-Art Language Laboratory Is Used for Listening

International Journal of English Studies IJES UNIVERSITY OF MURCIA www.um.es/ijes Online Dictionaries and the Teaching/Learning of English in the Expanding Circle PEDRO A. FUERTES-OLIVERA* BEATRIZ PÉREZ CABELLO DE ALBA Universidad de Valladolid / UNED Received: 10 February 2011 / Accepted: 22 April 2011 ABSTRACT This article follows current research on English for Specific Business Purposes, which focuses on the analysis of contextualized business genres and on identifying the strategies that can be associated with effective business communication (Nickerson, 2005). It explores whether free internet dictionaries can be used for promoting effective business communication by presenting a detailed analysis of the definitions and encyclopedic information associated with three business terms that are retrieved from YourDictionary.com, and BusinessDictionary.com. Our results indicate that these two dictionary structures can be very effective for acquiring business knowledge in cognitive use situations. Hence, this paper makes a case for presenting free internet dictionaries as adequate tools for guiding instructors and learners of Business English into the new avenues of knowledge that are already forming, which are characterized by an interest in continuous retraining, especially in the field of ESP where both teachers and students have to deal with areas of knowledge with which they might not be very familiar. KEYWORDS: Internet; Business Dictionary; Business English; Knowledge; Definitions; Encyclopaedic Information RESUMEN En el campo del Inglés para Finés Específicos la investigación actual está muy relacionada con el estudio del genre, y sus implicaciones retóricas, docentes y discursivas. Por ejemplo, Nickerson (2005) edita un número monográfico de English for Specific Purposes dedicado al Business English como lingua franca de la comunicación empresarial internacional. -

Redalyc.English As a Lingua Franca in Higher Education: Implications For

Ibérica ISSN: 1139-7241 [email protected] Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos España Björkman, Beyza English as a lingua franca in higher education: Implications for EAP Ibérica, núm. 22, 2011, pp. 79-100 Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos Cádiz, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=287023888005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 04 IBERICA 22.qxp:Iberica 13 21/09/11 17:01 Página 79 English as a lingua franca in higher education: Implications for EAP Beyza Björkman Stockholm University (Sweden) and Roskilde University (Denmark) [email protected] Abstract The last decade has brought a number of changes for higher education in continental Europe and elsewhere, a major one being the increasing use of English as a lingua franca (ELF) as the medium of instruction. With this change, EAP is faced with a new group of learners who will need to use it predominantly in ELF settings to communicate with speakers from other first language backgrounds. This overview paper first discusses the changes that have taken place in the field of EAP in terms of student body, followed by an outline of the main findings of research carried out on ELF. These changes and the results of recent ELF research have important implications for EAP instruction and testing. It is argued here that EAP needs to be modified accordingly to cater for the needs of this group. -

An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity the Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity The Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers Sarah Dawn Cooper West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the German Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Sarah Dawn, "An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity The Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3848. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3848 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity The Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers Sarah Dawn Cooper Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in World Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics Cynthia Chalupa, Ph.D., Chair Jonah Katz, Ph.D. -

Syntax-Semantics Interface

: Syntax-Semantics Interface http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/mitecs/chierchia.html Subscriber : California Digital Library » LOG IN Home Library What's New Departments For Librarians space GO REGISTER Advanced Search The CogNet Library : References Collection : Table of Contents : Syntax-Semantics Interface «« Previous Next »» A commonplace observation about language is that it consists of the systematic association of sound patterns with meaning. SYNTAX studies the structure of well-formed phrases (spelled out as sound sequences); SEMANTICS deals with the way syntactic structures are interpreted. However, how to exactly slice the pie between these two disciplines and how to map one into the other is the subject of controversy. In fact, understanding how syntax and semantics interact (i.e., their interface) constitutes one of the most interesting and central questions in linguistics. Traditionally, phenomena like word order, case marking, agreement, and the like are viewed as part of syntax, whereas things like the meaningfulness of a well-formed string are seen as part of semantics. Thus, for example, "I loves Lee" is ungrammatical because of lack of agreement between the subject and the verb, a phenomenon that pertains to syntax, whereas Chomky's famous "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" is held to be syntactically well-formed but semantically deviant. In fact, there are two aspects of the picture just sketched that one ought to keep apart. The first pertains to data, the second to theoretical explanation. We may be able on pretheoretical grounds to classify some linguistic data (i.e., some native speakers' intuitions) as "syntactic" and others as "semantic." But we cannot determine a priori whether a certain phenomenon is best explained in syntactic or semantics terms.