Integration and the Economy. Silesia in the Early Modern Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kamienna Góra

STRESZCZENIE PLANU URZĄDZENIA LASU NADLEŚNICTWA KAMIENNA GÓRA OBOWIĄZUJĄCEGO W LATACH 2019-2028 CELE GOSPODAROWANIA: W Nadleśnictwie Kamienna Góra najważniejszymi celami gospodarki leśnej w najbliższych okresach gospodarczych będą: 1) przeciwdziałanie zjawisku nadmiernej akumulacji surowca drzewnego na pniu w drzewostanach rębnych i przeszłorębnych, 2) obniżenie przeciętnego wieku drzewostanów nadleśnictwa, 3) poprawa powierzchniowej struktury klas wieku drzewostanów i zbliżenie jej do pożądanego układu klas wieku lasu normalnego, 4) utrzymanie lub poprawienie stanu stabilności, zdrowotności, zgodności z siedliskiem i jakości drzewostanów, 5) ochrona cennych elementów środowiska przyrodniczego występujących na gruntach w zarządzie nadleśnictwa. OGÓLNA CHARAKTERYSTYKA LASÓW NADLESNICTWA 1. Położenie, powierzchnia: Nadleśnictwo Kamienna Góra podlega Regionalnej Dyrekcji Lasów Państwowych we Wrocławiu. Jest nadleśnictwem dwu obrębowym, składającym się z obrębów Kamienna Góra i Lubawka. Obszar Nadleśnictwa graniczy z następującymi jednostkami LP: • od północy z Nadleśnictwem Jawor, • od wschodu z Nadleśnictwem Wałbrzych, • od zachodu z Nadleśnictwem Śnieżka. Natomiast od południa graniczy z Republiką Czeską. ZESTAWIENIE POWIERZCHNI NADLEŚNICTWA KAMIENNA GÓRA, WG STANU NA 1.01.2019 Obręb Nadleśnictwo L.p. Cecha Kamienna Góra Lubawka Powierzchnia1 - ha % 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Powierzchnia ogółem 7730,44 8400,24 16130,68 100,00 2 Grunty leśne (razem) 7606,32 8250,31 15856,63 98,30 3 Grunty zalesione 7401,16 7979,49 15380,65 95,35 4 Grunty niezalesione 20,09 23,57 43,66 0,27 5 Grunty zw. z gosp. leśną 185,07 247,25 432,32 2,68 Grunty nie zaliczone do 6 124,12 149,93 274,05 1,70 lasów 7 - w tym grunty do zales. - - - - 1 Powierzchnia bez współwłasności. 1.1. Podział na leśnictwa Nadleśnictwo jest podzielone na 14 leśnictw terytorialnych. -

Albert Breyer's Life and Work Is Closely Connected to the Fate of the Germans of Central Poland and to the Historic Events Between the Two World Wars

Jutta Dennerlein: Breyer the Researcher 1 of 10 Breyer the Researcher Albert Breyer's life and work is closely connected to the fate of the Germans of Central Poland and to the historic events between the two World Wars. This article wants to cover some of the circumstances which had influence on Albert Breyer's life and work. Research for the Heimat As a teacher Albert Breyer belonged to the intellectuals among the German minor- ity in Poland. Already during his stay at St. Petersburg (1913-1918) Breyer got in contact with the publication Geistiges Leben, a monthly periodical for the Germans in Russia. This periodical was initiated by two idealistic teachers from the Dobriner Land and was published in Łódź by Adolf Eichler and Ludwig Wolff. It's subject were the hardships of teachers who had been sent to backward colonies. It supported in a somewhat idealistic way their striving for intellectual challenge, informed about recent teaching methods and also covered the latest developments in questions of the German and Lutheran minorities in Łódź, Poland and Russia. This publication must have had great impact on the young teacher Albert Breyer. He could easily identify himself and his situation in most of the raised questions and issues. Returned to Łódź, Albert Breyer got in touch with Adolf Eichler. Adolf Eichler, who lived in Łódź, was one of the leading characters within the movement of the ethnic Germans in Łódź. He published the daily newspaper Lodzer Rundschau and published during World War I the Deutsche Post and the monthly periodical Geistiges Leben. -

Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Streets 3 I-- ' O LL G OREGON CITY, OREGON

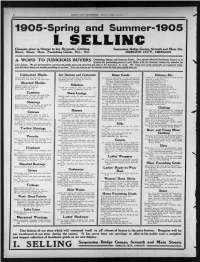

OREGON CITY ENTERPRISE, FRIDAY, APRIL 14, l!0o. (LflDTmOTTD On , Cheapest place in Oregon to buy Dry-goods- Clothing, Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Sts. Boots, Shoes, Hats, Furnishing Goods, Etc., Etc. OREGON CITY, OREGON A. "WORD JUDICIOUS ' BUYERS Conccyning Spring and Summer Goods. Out special effort for the Spring Season is to TO increase the purchasing power of yof Dollar with the Greatest values ever afforded for your money." We are determined to convince the public more and more that out store is the best place to trade. We want yoar trade constantly and regularly when- ever the future finds you needing anything in out tine. Yog can always get the lowest prices for first class goods from ts Unbleached Muslin Art Denims and Cretonnes Dress Goods Notions, Etc. 36 inch wide, best LL, per yard, 5c. Art denims, 36 inch wide, per yard, 15e. Our line of dress goods for the Spring and Clark's O. N. T. spool cotton, 6 spools for 25o 36 inch wide, best Cabot W, per yard, 6y2c. Cretonnes, figured, oil finish, per yard, 8c. Summer of 1905 is a wonderful collection San silk, 2 spools for 5c. ' Twilled heavy, per yard, 10c. of elegant designs and fabrics of the newest Bone crochet hooks, 2 for 5c. Bleached Muslins and most popular fashions for the coming Knitting needles, set, 5c. season. Prices are uniformly low. Besf Eagle pins, 5c paper. Common quality, per yard, 5c. Silkoline 34 inch wide cashmere per yard 15c. Embroidery silk, 3 skeins for 10c. Medium grade, per yard, 7c. -

The Untapped Potential of Scenic Routes for Geotourism: Case Studies of Lasocki Grzbiet and Pasmo Lesistej (Western and Central Sudeten Mountains, SW Poland)

J. Mt. Sci. (2021) 18(4): 1062-1092 e-mail: [email protected] http://jms.imde.ac.cn https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-020-6630-1 Original Article The untapped potential of scenic routes for geotourism: case studies of Lasocki Grzbiet and Pasmo Lesistej (Western and Central Sudeten Mountains, SW Poland) Dagmara CHYLIŃSKA https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2517-2856; e-mail: [email protected] Krzysztof KOŁODZIEJCZYK* https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3262-311X; e-mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Department of Regional Geography and Tourism, Institute of Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Earth Sciences and Environmental Management, University of Wroclaw, No.1, Uniwersytecki Square, 50–137 Wroclaw, Poland Citation: Chylińska D, Kołodziejczyk K (2021) The untapped potential of scenic routes for geotourism: case studies of Lasocki Grzbiet and Pasmo Lesistej (Western and Central Sudeten Mountains, SW Poland). Journal of Mountain Science 18(4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-020-6630-1 © The Author(s) 2021. Abstract: A view is often more than just a piece of of GIS visibility analyses (conducted in the QGIS landscape, framed by the gaze and evoking emotion. program). Without diminishing these obvious ‘tourism- important’ advantages of a view, it is noteworthy that Keywords: Scenic tourist trails; Scenic drives; View- in itself it might play the role of an interpretative tool, towers; Viewpoints; Geotourism; Sudeten Mountains especially for large-scale phenomena, the knowledge and understanding of which is the goal of geotourism. In this paper, we analyze the importance of scenic 1 Introduction drives and trails for tourism, particularly geotourism, focusing on their ability to create conditions for Landscape, although variously defined (Daniels experiencing the dynamically changing landscapes in 1993; Frydryczak 2013; Hose 2010; Robertson and which lies knowledge of the natural processes shaping the Earth’s surface and the methods and degree of its Richards 2003), is a ‘whole’ and a value in itself resource exploitation. -

The British Linen Trade with the United States in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1990 The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries N.B. Harte University College London Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Harte, N.B., "The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries" (1990). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 605. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/605 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -14- THE BRITISH LINEN TRADE WITH THE UNITED STATES IN THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES by N.B. HARTE Department of History Pasold Research Fund University College London London School of Economics Gower Street Houghton Street London WC1E 6BT London WC2A 2AE In the eighteenth century, a great deal of linen was produced in the American colonies. Virtually every farming family spun and wove linen cloth for its own consumption. The production of linen was the most widespread industrial activity in America during the colonial period. Yet at the same time, large amounts of linen were imported from across the Atlantic into the American colonies. Linen was the most important commodity entering into the American trade. This apparently paradoxical situation reflects the importance in pre-industrial society of the production and consumption of the extensive range of types of fabrics grouped together as 'linen*. -

MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City Major Disturbance

In Breslau, the overthrow of the imperial authorities passed off without MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City major disturbance. On 8 November, a Loyal Appeal for the citizens to uphold by Norman Davies (pp. 326-379) their duties to the Kaiser was distributed in the names of the Lord Mayor, Paul Matting, Archbishop Bertram and others. But it had no great effect. The Commander of the VI Army Corps, General Pfeil, was in no mood for a fight. Breslau before and during the Second World War He released the political prisoners, ordered his men to leave their barracks, 1918-45 and, in the last order of the military administration, gave permission to the Social Democrats to hold a rally in the Jahrhunderthalle. The next afternoon, a The politics of interwar Germany passed through three distinct phases. In group of dissident airmen arrived from their base at Brieg (Brzeg). Their arrival 1918-20, anarchy spread far and wide in the wake of the collapse of the spurred the formation of 'soldiers' councils' (that is, Soviets) in several military German Empire. Between 1919 and 1933, the Weimar Republic re-established units and of a 100-strong Committee of Public Safety by the municipal leaders. stability, then lost it. And from 1933 onwards, Hitler's 'Third Reich' took an The Army Commander was greatly relieved to resign his powers. ever firmer hold. Events in Breslau, as in all German cities, reflected each of The Volksrat, or 'People's Council', was formed on 9 November 1918, from the phases in turn. Social Democrats, union leaders, Liberals and the Catholic Centre Party. -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Classification of Synoptic Conditions of Summer Floods in Polish

water Article Classification of Synoptic Conditions of Summer Floods in Polish Sudeten Mountains Ewa Bednorz 1,* , Dariusz Wrzesi ´nski 2 , Arkadiusz M. Tomczyk 1 and Dominika Jasik 2 1 Department of Climatology, Adam Mickiewicz University, 61-680 Pozna´n,Poland 2 Department of Hydrology and Water Management, Adam Mickiewicz University, 61-680 Pozna´n,Poland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-61-829-6267 Received: 24 May 2019; Accepted: 12 July 2019; Published: 13 July 2019 Abstract: Atmospheric processes leading to extreme floods in the Polish Sudeten Mountains were described in this study. A direct impact of heavy precipitation on extremely high runoff episodes was confirmed, and an essential role of synoptic conditions in triggering abundant rainfall was proved. Synoptic conditions preceding each flood event were taken into consideration and the evolution of the pressure field as well as the moisture transport was investigated using the anomaly-based method. Maps of anomalies, constructed for the days prior to floods, enabled recognizing an early formation of negative centers of sea level pressure and also allowed distinguishing areas of positive departures of precipitable water content over Europe. Five cyclonic circulation patterns of different origin, and various extent and intensity, responsible for heavy, flood-triggering precipitation in the Sudetes, were assigned. Most rain-bringing cyclones form over the Mediterranean Sea and some of them over the Atlantic Ocean. A meridional southern transport of moisture was identified in most of the analyzed cases of floods. Recognizing the specific meteorological mechanisms of precipitation enhancement, involving evolution of pressure patterns, change in atmospheric moisture and occurrence of precipitation may contribute to a better understanding of the atmospheric forcing of floods in mountain areas and to improve predicting thereof. -

![Soils of Lower Silesia [Gleby Dolnego Śląska]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5667/soils-of-lower-silesia-gleby-dolnego-%C5%9Bl%C4%85ska-775667.webp)

Soils of Lower Silesia [Gleby Dolnego Śląska]

GLEBY DOLNEGO ŚLĄSKA: geneza, różnorodność i ochrona SOILS OF LOWER SILESIA: origins, diversity and protection SOILS of Lower Silesia: origins, diversity and protection Monograph edited by Cezary Kabała Polish Society of Soil Science Wrocław Branch Polish Humic Substances Society Wrocław 2015 GLEBY Dolnego Śląska: geneza, różnorodność i ochrona Praca zbiorowa pod redakcją Cezarego Kabały Polskie Towarzystwo Gleboznawcze Oddział Wrocławski Polskie Towarzystwo Substancji Humusowych Wrocław 2015 Autorzy (w porządku alfabetycznym) Contributors (in alphabetic order) Jakub Bekier Andrzej Kocowicz Tomasz Bińczycki Mateusz Krupski Adam Bogacz Grzegorz Kusza Oskar Bojko Beata Łabaz Mateusz Cuske Marian Marzec Irmina Ćwieląg-Piasecka Agnieszka Medyńska-Juraszek Magdalena Dębicka Elżbieta Musztyfaga Bernard Gałka Zbigniew Perlak Leszek Gersztyn Artur Pędziwiatr Bartłomiej Glina Ewa Pora Elżbieta Jamroz Agnieszka Przybył Paweł Jezierski Stanisława Strączyńska Cezary Kabała Katarzyna Szopka Anna Karczewska Rafał Tyszka Jarosław Kaszubkiewicz Jarosław Waroszewski Dorota Kawałko Jerzy Weber Jakub Kierczak Przemysław Woźniczka Recenzenci Reviewers Tadeusz Chodak Michał Licznar Jerzy Drozd Stanisława Elżbieta Licznar Stanisław Laskowski Polskie Towarzystwo Gleboznawcze Oddział Wrocławski Polskie Towarzystwo Substancji Humusowych Redakcja: Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy we Wrocławiu Instytut Nauk o Glebie i Ochrony Środowiska 50-357 Wrocław, ul. Grunwaldzka 53 Druk i oprawa: Ultima-Druk Sp z o.o. 51-123 Wrocław, ul. W. Pola 77a ISBN 978-83-934096-4-8 Monografia -

Charakterystyka Obszaru Powiatu Jeleniogórskiego

CHARAKTERYSTYKA OBSZARU POWIATU JELENIOGÓRSKIEGO WYDZIAŁ ARCHITEKTURY POLITECHNIKI WROCŁAWSKIEJ INFORMACJE OGÓLNE POWIERZCHNIA GĘSTOŚĆ ZALUDNIENIA STRUKTURA POWIERZCHNI BEZROBOTNI POWIAT JELENIOGÓRSKI składa się z: 1 miasta na prawach powiatu – Jelenia Góra 4 gmin miejskich – Karpacz, Kowary, Piechowice, Szklarska Poręba 5 gmin wiejskich – Janowice Wielkie, Jeżów Sudecki, Mysłakowice, Podgórzyn, Stara Kamienica L.p. Jednostka terytorialna Ludność Powierzchnia Gęstość zaludniania [km2] [os/km2] 1. Powiat jeleniogórski 63 757 627 102 2. Karpacz (gm. m) 5 004 39 128 3. Kowary (gm. m) 11 579 37 313 4. Piechowice (gm. m) 6 496 43 151 5. Szklarska Poręba (gm. m) 6 970 75 93 6. Janowice Wielkie (gm. w) 4 074 57 71 7. Jeżów Sudecki (gm. w) 6 544 94 70 8. Mysłakowice (gm. wiejska) 10 058 88 114 9. Podgórzyn (gm. w) 7 783 83 94 10. Stara Kamienica (gm. w) 5 249 111 47 11. Powiat m. Jelenia Góra 85 378 109 783 WOJEWÓDZTWO 12. DOLNOŚLĄSKIE 2 877 059 19 947 144 POWIERZCHNIA, STAN LUDNOŚCI (stan na 2008 rok) źródło GUS Jednostka Użytki rolne Lasy grunty leśne Pozostałe grunty i nieużytki terytorialna ha % ha % ha % Karpacz 397 10 2 479 65 920 24 Kowary 816 22 2 444 65 479 13 Piechowice 960 22 2 892 67 477 11 Szklarska Poręba 428 6 6 361 84 753 10 Janowice Wielkie 3 045 52 2 360 41 404 7 Jeżów Sudecki 5 838 62 2 762 29 838 9 Mysłakowice 4 263 48 3 690 42 922 10 Podgórzyn 2 964 36 4 325 52 958 12 Stara Kamienica 6 193 56 4 098 37 755 7 Jelenia Góra 4 248 39 3 695 34 2 893 27 STRUKTURA POWIERZCHNI (stan na 2005 rok) źródło GUS Powierzchnia użytków rolnych, -

Lower Silesian Voivodshipx

Institute of Enterprise Collegium of Business Administration (KNoP) Warsaw School of Economics (SGH) Investment attractiveness of regions 2010 Lower Silesian voivodship Hanna Godlewska-Majkowska Patrycjusz Zarębski 2010 Warsaw, October 2010 The profile of regional economy of Lower Silesian voivodship Lower Silesian voivodship belongs to the most attractive regions of Poland from investors’ point of view. Its advantages are: - a very high level of economic development, significantly exceeding the national average, - a highly beneficial geopolitical location by virtue of the proximity of Germany and the Czech Republic as well as an attractive location in view of sales markets of agglomerations of Prague, Berlin and Warsaw, - very well-developed transport infrastructure (road, railways, waterways, airways) and communications infrastructure: • convenient road connections: A4 highway, international roads: E40, E36, E65 and E67, • an expanded system of railways: international railways E30 and E59, • a well-developed network of water transport (the Oder system enables to ship by barges from Lower Silesia to the port complex of Szczecin-Świnouj ście and through the Oder-Spree and Oder-Havel channels Lower Silesia is connected to the system of inland waterways of Western Europe), • Copernicus Airport Wrocław in Wrocław-Strachowice offers international air connections with Frankfurt upon Main, Munich, London, Copenhagen, Milan, Dublin, Nottingham, Dortmund, Shannon, Glasgow, Liverpool, Stockholm, Cork and Rome, • a very good access to the Internet -

Hunting Shirts and Silk Stockings: Clothing Early Cincinnati

Fall 1987 Clothing Early Cincinnati Hunting Shirts and Silk Stockings: Clothing Early Cincinnati Carolyn R. Shine play function is the more important of the two. Shakespeare, that fount of familiar quotations and universal truths, gave Polonius these words of advice for Laertes: Among the prime movers that have shaped Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy, But not expressed infancy; history, clothing should be counted as one of the most potent, rich not gaudy; For the apparel oft proclaims the man.1 although its significance to the endless ebb and flow of armed conflict tends to be obscured by the frivolities of Laertes was about to depart for the French fashion. The wool trade, for example, had roughly the same capital where, then as now, clothing was a conspicuous economic and political significance for the Late Middle indicator of social standing. It was also of enormous econo- Ages that the oil trade has today; and, closer to home, it was mic significance, giving employment to farmers, shepherds, the fur trade that opened up North America and helped weavers, spinsters, embroiderers, lace makers, tailors, button crack China's centuries long isolation. And think of the Silk makers, hosiers, hatters, merchants, sailors, and a host of others. Road. Across the Atlantic and nearly two hundred If, in general, not quite so valuable per pound years later, apparel still proclaimed the man. Although post- as gold, clothing like gold serves as a billboard on which to Revolution America was nominally a classless society, the display the image of self the individual wants to present to social identifier principle still manifested itself in the quality the world.