The CHAIRMAN. NOW, Our Next Distinguished Panel Is Comprised Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's Constitutional Narrative

America’s Constitutional Narrative Laurence H. Tribe Abstract: America has always been a wonderfully diverse place, a country where billions of stories span- ning centuries and continents converge under the rubric of a Constitution that unites them in an ongoing narrative of national self-creation. Rather than rehearse familiar debates over what our Constitution means, this essay explores what the Constitution does. It treats the Constitution as a verb–a creative and contested practice that yields a trans-generational conversation about the meaning of our past, the im- Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/daed/article-pdf/141/1/18/1830095/daed_a_00126.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 peratives of our present, and the values and aspirations that should point us toward our future. And it meditates on how this practice, drawing deeply on the capacious wellsprings of text and history, simulta- neously reinforces the political order and provides a language for challenging its legitimacy, thereby con- stituting us as “We, the People,” joined in a single project framed centuries ago that nevertheless remains inevitably our own. What is the Constitution? This question has puzzled many of its students and conscripted whole forests in the service of books spelling out grand theories of constitutional meaning. In their quest to resolve this enigma, scholars have power- fully illuminated both the Constitution’s inescap- LAURENCE H. TRIBE, a Fellow of able writtenness and its unwritten extensions, its the American Academy since 1980, bold enumeration of rights and its construction of is the Carl M. Loeb University Pro- structural protections lest those rights become fessor and Professor of Constitu- mere “parchment barriers,” and the centuries-long tional Law at Harvard Law School. -

Editor's Letter

Editor’s Letter Every quarter when it is time to prepare the next Newsletter for distribution, my husband asks me why I ever agreed to do this, given the hours it takes, and given that I usually demur on my other duties around the house. It’s never been a question for me: the desire to give back to an organization that gave me such a unique and enriching experience is overwhelming. Especially now that I have Ien Cheng, our new Deputy Editor to help share the responsibilities of putting these issues together. Ien comes to us with more publishing experience than anyone else on the team, Ushma Savla Neill,Neill Managing Editor having served as Publisher and Managing Editor of FT.com and now chief of staff of Bloomberg’s global multimedia group. (Northwestern, BS 996, MS 996, Ph.D. 1999; Sherfield Postdoctoral Fellow, Impe- Together, the contributors below and I bring you another spectacular issue featuring some extraordinary individuals. Bryan Leach profiles Kathleen Sullivan (Oxford ’76), rial College 1999) As a Marshall Sherfield who has served as AMS President and Dean of Stanford Law School and was the Fellow, Ushma studied the mechanics of the first woman to become a named partner at one of America’s 200 largest law firms. vascular system at Imperial College, Lon- Nick Hartman got a chance to talk to 3 alumni who are launching their careers in don. She returned to the US in 2001, and diplomacy – in Sudan and in the Middle East. We also feature an update on the after 2 years as an editor at the biomedical shenanigans of the class of 2010 from the class secretary Aroop Mukharji. -

The Discourse Ethics Alternative to Rust V. Sullivan Gary Charles Leedes University of Richmond

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 26 | Issue 1 Article 4 1991 The Discourse Ethics Alternative to Rust v. Sullivan Gary Charles Leedes University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Gary C. Leedes, The Discourse Ethics Alternative to Rust v. Sullivan, 26 U. Rich. L. Rev. 87 (1991). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol26/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DISCOURSE ETHICS ALTERNATIVE TO RUST v. SULLIVAN Gary Charles Leedes* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 88 II. A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF RUST V. SULLIVAN ...... 91 A. Overview of the So-Called Gag Rule Regulations 91 B. A Closer Look at the Content and Context of the R egulations ................................. 92 1. Historical Background of Title X Regulations 92 2. The New Regulations ..................... 94 III. THE LIMITATIONS OF LEGAL THEORY ................ 98 A. The Impotence of Legal Scholarship .......... 98 1. The Critical Legal Studies Movement ...... 98 2. The Law and Economics Approach ........ 99 3. Process-Oriented Theory .................. 100 4. Rights-Oriented Jurisprudence ............ 101 5. Communitarianism ....................... 101 6. The Law and Literature Movement ........ 102 7. Do Theories Have Consequences? . 103 B. A Half-Hearted Doctrine of Unconstitutional Conditions .................................. 105 C. The Paradigms of Positivism and of Communicative Action Compared ............ -

Foreword: Loving Lawrence

Michigan Law Review Volume 102 Issue 7 2004 Foreword: Loving Lawrence Pamela S. Karlan Stanford Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Pamela S. Karlan, Foreword: Loving Lawrence, 102 MICH. L. REV. 1447 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol102/iss7/1 This Colloquium is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOREWORD: LOVING LAWRENCE Pamela S. Karlan* When you come to a fork in the road, take it. - Lawrence Peter (Yogi) Berra Two interracial couples. Two cases. Two clauses. In Loving v. Virginia,1 the Supreme Court struck down a Virginia statute outlawing interracial marriage. In Lawrence v. Texas,2 the Court struck down a Texas statute outlawing sexual activity between same-sex individuals. Each case raised challenges under both the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Loving marked the crystallization, a dozen years after Brown,3 of the antisubordination principle: Virginia's law ran afoul of the Equal Protection Clause because it reflected nothing more than arbitrary and invidious discrimination "designed to maintain White Supremacy."4 In reaching that conclusion, the Court employed a then-novel formulation: strict scrutiny.5 Chief Justice Warren noted that in cases * Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Professor of Public Interest Law, Stanford Law School. -

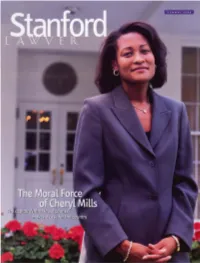

Summer 1999 ~Tanfor~ Law ~C~Ool [Xecutive [~Ucation Programs

Summer 1999 ~tanfor~ law ~c~ool [xecutive [~ucation Programs Since 1993 the Executive Education Programs at Stanford Law School have provided a national forum for leaders in the business and legal communities to share their expertise. Our law and business faculty will challenge and inspire you. We invite you to Jam us. ': .. This was the most beneficial course I've attended in my career. " Directors' College '99 Parricipant Mark Segura, CLECO Corporation 'Informal discussion and associating with other participants is very valuable-just bringing this group together is worthwhile. " General Counsel '98 Parricipant Contact us: Executive Education Phone: (650) 723-5905 Fax: (650) 72P861 Visit us at our website: http://lawschool.stanford.edu/execed ISSUE55 / SUMMER 1999 FEATURLS 18 PAUL BREST'S FOOTSTEPS A confluence of events 12 years ago fated Paul Brest's deanship to a troubled infancy. But Brest's relentless quest for improvement-his own and the Law School's-ensured that those baby steps would become historic strides. 26 THE STORY OF A SENTENCE 12 Does this guy deserve three years in jail? Yes, says an DAUGHTER OF A SOLDIER assistant U.s. attorney, who does his best to string With the poise of a veteran together a sentence that makes sense. and the confidence of her convictions, 33-year-old Cheryl Mills defended the Presidency, woke up the Senate, and wowed 3 Washington. Sullivan's appointment as Dean makes a splash Gunther, Babcock add to their honors Two faculty earn tenure Antitrust legend William Baxter dies A new book on "don't ask, -

Interview with Kathleen Sullivan # ISE-A-L-2011-059.01 Interview # 1: December 14, 2011 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Kathleen Sullivan # ISE-A-L-2011-059.01 Interview # 1: December 14, 2011 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Wednesday, December 14, 2011. My name is Mark DePue, the Director of Oral History with the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. This morning I’m delighted to have Kathleen Sullivan on the phone. Good morning Kathleen. Sullivan: Good morning. Thank you very much for this opportunity. DePue: Well why don’t you tell us why we’re not doing this in person, which is the way I like to do things. Sullivan: Well, it certainly would be an honor and a pleasure to get together on it, but I’m at the point in life where traveling around does not appeal to me any more, though I loved it when I was younger. -

The Project of the Harvard Forewords: a Social and Intellectual Inquiry

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Constitutional Commentary 1995 The rP oject of the Harvard Forewords: A Social and Intellectual Inquiry. Mark Tushnet Timothy Lynch Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tushnet, Mark and Lynch, Timothy, "The rP oject of the Harvard Forewords: A Social and Intellectual Inquiry." (1995). Constitutional Commentary. 680. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm/680 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Constitutional Commentary collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROJECf OF THE HARVARD FOREWORDS: A SOCIAL AND INTELLECTUAL INQUIRY Mark Tushnet* and Timothy Lynch** Since 1951 the editors of the Harvard Law Review have se lected a prominent scholar of constitutional law to write a "Fore word" to the Review's annual survey of the work of the Supreme Court. Within the community of scholars of constitutional law the "Forewords" are widely taken to be good indications of the state of the field. The Foreword project defines a vision of the field of constitutional scholarship. After describing the history and current reputation of the Forewords, this Essay examines some of the structural constraints on the project. It concludes with an analysis of some dimensions of the intellectual project the Forewords have defined. In addition to proposing a modest revision of the accepted understanding of the intellectual history of constitutional law scholarship, we hope that, by suggesting a less-than-obvious connection between constitutional scholarship and constitutional law, the analysis can give us insight into the directions constitutional law scholarship may take in the next decade. -

Teaching Slavery in American Constitutional Law Paul Finkelman

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 Teaching Slavery in American Constitutional Law Paul Finkelman Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Finkelman, Paul (2001) "Teaching Slavery in American Constitutional Law," Akron Law Review: Vol. 34 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol34/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Finkelman: Teaching Slavery in Constitutional Law TEACHING SLAVERY IN AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW by Paul Finkelman* From 1787 until the Civil War, slavery was probably the single most important economic institution in the United States. On the eve of the Civil War, slave property was worth at least two billion dollars.1 In the aggregate, the value of all the slaves in the United States exceeded the total value of all the nations railroads or all its factories. Slavery led to two major political compromises of the antebellum period,2 as well as to the most politically divisive Supreme Court decision in our history.3 Vast amounts of political and legal energy went into dealing with the institution. -

America's Constitutional Narrative Laurence H. Tribe

America’s Constitutional Narrative Laurence H. Tribe Abstract: America has always been a wonderfully diverse place, a country where billions of stories span- ning centuries and continents converge under the rubric of a Constitution that unites them in an ongoing narrative of national self-creation. Rather than rehearse familiar debates over what our Constitution means, this essay explores what the Constitution does. It treats the Constitution as a verb–a creative and contested practice that yields a trans-generational conversation about the meaning of our past, the im- peratives of our present, and the values and aspirations that should point us toward our future. And it meditates on how this practice, drawing deeply on the capacious wellsprings of text and history, simulta- neously reinforces the political order and provides a language for challenging its legitimacy, thereby con- stituting us as “We, the People,” joined in a single project framed centuries ago that nevertheless remains inevitably our own. What is the Constitution? This question has puzzled many of its students and conscripted whole forests in the service of books spelling out grand theories of constitutional meaning. In their quest to resolve this enigma, scholars have power- fully illuminated both the Constitution’s inescap- LAURENCE H. TRIBE, a Fellow of able writtenness and its unwritten extensions, its the American Academy since 1980, bold enumeration of rights and its construction of is the Carl M. Loeb University Pro- structural protections lest those rights become fessor and Professor of Constitu- mere “parchment barriers,” and the centuries-long tional Law at Harvard Law School. dance of text, original meaning, history and tradi- The recipient of ten honorary de- tion, judicial doctrine, social movements, and aspi- grees, he was appointed by the rational values. -

Leading Women Lawyers in New York City, Powered by Crain’S Custom, Are Trailblaz- Ers Who Found Multiple Paths to Excellence

An Advertising Supplement to Crain’s New York Business Meet some of the New York Bar’s most talented lawyers, who just happen to be women The 100 New Yorkers named to the inaugural list of Leading Women Lawyers in New York City, powered by Crain’s Custom, are trailblaz- ers who found multiple paths to excellence. Some are partners and practice leaders at the city’s big law firms, others corporate counsel at Manhattan companies. Some unabashedly champion their fellow minority female attorneys, while others feed their passions for public service by donating their time generously to pro bono causes. These are women who juggle both distinguished careers and exceptional civic and philanthropic activities. In acknowledging the talents of to the heights of their careers against Morales advises law firms to keep close these 100 women, Crain’s is merely a background of sometimes blatant, watch on who they elevate to partner. sometimes unconscious bias. Only If there are too few women, they must tapping into New York’s rich history a very foolish man, though, would reassess whether females have access of female lawyers who refused to try to objectify or demean these to power in the firm structure, and be defined by their gender. gifted attorneys. guard against unconscious bias and blind spots. Law firms must also lean on Since the 1800s, the state has been “When someone said obnoxious specific tools that cultivate the careers of home to “amazing trailblazing women things or made a stupid comment, I younger female attorneys and give them attorneys who broke through barriers was so incredulous I’d laugh and say, access to training, client development, and blatant discrimination to make ‘Are you kidding me?’ because it was mentoring and management opportu- major contributions in the legal profes- so ridiculous,” said Terri Adler, who nities. -

Honorabl~:A~;, Has Elias, J Tlon's Looked to the Na Forgotten Past to Forge a New Type of Justice

Stanf HAIL TO THE CHIEF Zealand's court New tem Is breaking sys Its colonial away from Ight traditions. The R slan Honorabl~:a~;, has Elias, J tlon's looked to the na forgotten past to forge a new type of Justice. What They Teach The Law School welcomes the opening of the Stanford Community Law Clinic THE CLINIC'S LAUNCH TEAM, Yvonne Mere, clinical supervising attorney and former 2117 University Ave. supervising attorney, Homeless Advocacy Project, San Francisco; Peter Reid CAB '64), clinjc director and former executive director, Legal Aid Society of San Mateo County; East Palo Alto Peggy Stevenson CAB '75), clinical supervising attorney and former executive director, East Palo Alto Community Law Project; Guadalupe (Lupe) Buenrostro, legal assis 650/475·0560 tant; and Gary Blasi, a visiting professor in clinical law from UCLA. he Stanford Community Law Clinic began assisting clients in January 2003. Its mission is to T serve low-income residents of East Menlo Park, East Palo Alto, Redwood City, and other nearby communities, while providing opportunities for the clinical training of Stanford Law School students. Operated and managed by the Law School in cooperation with the Legal Aid Society of San Mateo County, the clinic will focus on housing issues, workers' rights, and government benefits. Special thanks to: The Stanford University President's Fund Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Mamtt, Phelps & Phillips Bingham McCutchen Gordon & Rees Morrison & Foerster Cooley Godward Gray Cary Ware & Freidenrich PillsbUlY Winthrop Fenwick & West Hanson Bridgett Marcos Vlahos Rudy Townsend and Townsend and Crew Genentech Heller Ehrman White & McAuliffe \i\Tilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati FRO,\l TIlE DE \ 1 STANFORO LAWYER The Law School Goes Live BY KATHLEEN M. -

Kathleen Sullivan

NEWSLETTER 2010-11 SPRING • VOLUME 98, NUMBER 1 Centennial Kathleen Sullivan Celebrations— TA: Launching Register Now! Tomorrow’s Leaders August 12-14, 2011 By Elizabeth Tulis, SP96 TA01 Ithaca, New York Kathleen M. Sullivan, SP71 CB72 TA74, lic schools in the New York City area, Featuring is the Stanley Morrison Professor of and then on to Queens College—the • Keynote speech by Kathleen Sullivan Law and former Dean of Stanford Law first people in their families to go to • A book discussion event featuring School, and a partner at the law firm college. I was the firstborn child, and Danielle Evans, author of Before You of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan. I got the benefit of all of their teach- Suffocate Your Own Fool Self She is the first female name partner of ing and their love of books and ideas. an American Lawyer 100 firm. On Au- My mother was a schoolteacher. She October 14-16, 2011 gust 13, 2011, she will deliver the Key- taught Ojibway children at a tribal Ann Arbor, Michigan note Address at Telluride’s Centennial school in the Upper Peninsula of Celebration in Ithaca, NY. Michigan before I was born. My fa- Featuring ther was an accountant and financial In your previous interview for the • Keynote speech by Esther Dyson executive; he had been a navigator in Newsletter [published in 2004], you • A group service project event, with the Air Force. said that your TASPlication changed guided reflection on the meaning of I was born on an Air Force base your life. Could you tell me a bit service in the Upper Peninsula.