Models from the Past in Roman Culture Matthew B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMANS F/ 52 PART L: the KINGS of ROME

ruuLAE rcWAE STORIES OF FAMOLJS ROMANS f/ 52 PART l: THE KINGS OF ROME 1 iam dEdum: "for a long time already.' 2 aegrl ferre, to take badly, resent. Sex. Tarquinil: the youngest son ofTarquinius Superbus; see 11:17 and the note there" 3 ut . , . statuerent: "that they decided," result clause (see the grammar note on page 56). 5 Tarquinius CollEtlnus, -I (m.), Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus (nephew of Tarquinius Superbus and husband oflucretia). sorOre . n6tus: "born from the sister," ablative ofsourcewith nEtus, perfect participle ofthe verb n6scor. 6 contubernium, -i (n.), the sharing of a tent in the army, the status of be- ing messmates. in contuberrrid iuvenum rEgi0rum . erat: "was a messmate of . ." Ardea, -ae (f), Ardea (a town to the south of Rome). 7 *hber, libera, hberum, free, outspoken, unrestricted, unrestrained. frnusquisque, tnaquaeque, tnumquodque, each one. 8 *nutue, -ts (f), daughter-in-1aw. 9 *ltxus, -0.s (m.), luxury, luxurious living, extravagance. *d6prehend6, d6prehendere (3), dEprehendl, d6preh6nsum, to get hold of, surprise, catch in the act. CollEtia, -ae (f), Collatia (a town in Latium). 10 LucrEtia, -ae (f), Lucretia (wife of Collatinus). lanificium, -I (n.), wool-spinning, weaving (a traditional occupation of a Roman housewife). L1 offendO, offendere (3), offeadi, oftnsum, to strike against, find, en- counf,er. pudlcus, -a, -lrm, chase, virtuous. *itrdicd (1), to judge, proclaim, declare, think. 12 *corrump6, corrumpere (3), corrtrpl, corruptum, to break, corrupt, seduce, Ad quan corrumpendam: "To seduce her," gerundive (see the grammar note on page 59). 13 propinquitds, propinquitdtig (f), family relationship. Sextus Tarquinius was admitted to the house because he was a rela- tive. -

Horatius at the Bridge” by Thomas Babington Macauley

A Charlotte Mason Plenary Guide - Resource for Plutarch’s Life of Publicola Publius Horatius Cocles was an officer in the Roman Army who famously defended the only bridge into Rome against an attack by Lars Porsena and King Tarquin, as recounted in Plutarch’s Life of Publicola. There is a very famous poem about this event called “Horatius at the Bridge” by Thomas Babington Macauley. It was published in Macauley’s book Lays of Ancient Rome in 1842. HORATIUS AT THE BRIDGE By Thomas Babington Macauley I LARS Porsena of Clusium By the Nine Gods he swore That the great house of Tarquin Should suffer wrong no more. By the Nine Gods he swore it, And named a trysting day, And bade his messengers ride forth, East and west and south and north, To summon his array. II East and west and south and north The messengers ride fast, And tower and town and cottage Have heard the trumpet’s blast. Shame on the false Etruscan Who lingers in his home, When Porsena of Clusium Is on the march for Rome. III The horsemen and the footmen Are pouring in amain From many a stately market-place; From many a fruitful plain; From many a lonely hamlet, Which, hid by beech and pine, 1 www.cmplenary.com A Charlotte Mason Plenary Guide - Resource for Plutarch’s Life of Publicola Like an eagle’s nest, hangs on the crest Of purple Apennine; IV From lordly Volaterae, Where scowls the far-famed hold Piled by the hands of giants For godlike kings of old; From seagirt Populonia, Whose sentinels descry Sardinia’s snowy mountain-tops Fringing the southern sky; V From the proud mart of Pisae, Queen of the western waves, Where ride Massilia’s triremes Heavy with fair-haired slaves; From where sweet Clanis wanders Through corn and vines and flowers; From where Cortona lifts to heaven Her diadem of towers. -

Under the Influence of Art: the Effect of the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia on Valerius

Under the Influence of Art: The Effect of the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia on Valerius Maximus’ Facta et Dicta Memorabilia In his work, Facta et Dicta Memorabilia, Valerius Maximus stated in the praefatio of his chapter “De Fortitudine” that he will discuss the great deeds of Romulus, but cannot do so without bringing up one example first; someone whose similarly great deeds helped save Rome (3.2.1-2). This great man is Horatius Cocles. Valerius Maximus noted that he must next talk about another hero, Cloelia, after Horatius Cocles because they fight the same enemy, at the same time, at the same place, and both perform facta memorabilia to save Rome (3.2.2-3). Valerius Maximus mentioned Horatius Cocles and Cloelia together, as if they are a joined pair that cannot be separated. Yet there is another legendary figure, Mucius Scaevola, who also fights the same enemy, at the same time, and also performs facta memorabilia to save Rome. It is strange both that Valerius Maximus seemed compelled to unite Cloelia with the mention of Horatius Cocles, and also that he did not include Mucius Scaevola. Instead, Scaevola’s story is at the beginning of the next chapter (3.3.1). Traditionally these three heroes, Horatius Cocles, Cloelia, and Mucius Scaevola, were mentioned together by historians such as Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, whose works predate Valerius Maximus’ (Ab Urbe Condita 2.10-13, Roman Antiquities 5.23-35). Valerius Maximus was able to split up the triad, despite the tradition, without receiving flack because it had already been done by Virgil in the Aeneid, where he described the dual images of Cocles and Cloelia on Aeneas’ shield, but Scaevola is absent (8.646-651). -

2016 National Latin Exams

2016 ACL/NJCL NATIONAL LATIN EXAM INTRODUCTION TO LATIN EXAM A CHOOSE THE BEST ANSWER FROM A, B, C, OR D. MARK ANSWERS ON ANSWER SHEET. 1. What is the Roman name for the Greek god Hermes? A) Mercury B) Mars C) Vulcan D) Pluto 2. Which goddess is the mother of Cupid and has this bird as a symbol? A) Juno B) Venus C) Minerva D) Vesta 2. 3. The Roman numerals IV + VI = A) VII B) VIII C) IX D) X 4. A Latin teacher asking the name of a person in a picture would ask A) Ubi est? B) Quid agis? C) Quis est? D) Estne laetus? 5. Who in ancient Rome wore a toga praetexta? A) senator B) mater C) libertus D) servus 6. What is the best translation of the Latin motto festīnā lentē? A) hurry slowly B) happy birthday C) time flies D) seize the day 7. Based on the Latin root, who would be considered urbane? A) a sailor B) a city dweller C) a shepherd D) a nymph 8. At what large amphitheater would the Romans watch gladiatorial fights and animal hunts? A) the Forum B) the Curia C) the Colosseum D) the Pantheon 9. Sicilia is on the map in the area numbered A) 1 B) 2 C) 3 D) 4 9. 10. If a bird flew in a straight line from Hispania to Graecia, it would be 10. 2 flying A) north B) south C) east D) west 11. What Latin abbreviation means “and the rest”? A) P.S. B) a.m. -

Clarissimi Viri Joshua Roberts

Clarissimi Viri Joshua Roberts Livy’s histories of Horatius Cocles and Gnaeus Marcius Coriolanus The University of Georgia Department of Classics Summer Institute June, 2015 Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit. 1 Tibi, Domine, qui me potentem facit. Maximas gratias fidelissimae uxori carissimisque liberis, qui semper efficiunt me laetum domum redire. Thank you to my Latin teachers: Mrs. Counts, Mr. Spearman, and Ms. Brown for introducing me to Latin. Mr. Philip W. Rohleder, who was the very embodiment of what my career has become. Uncle Phil, I cannot thank you enough for your friendship and your excellent example. I am still trying to be like you. Dr. Evelyn Tharpe, Dr. Ron Bohrer, and Dr. Josh Davies at the University of Tenneessee at Chattanooga. Dr. Bohrer, you showed me how to be merciful as a teacher. My professors in the University of Georgia Summer Institute faculty: Dr. Christine Albright, Dr. Naomi Norman, Dr. Robert Harris, Dr. John Nicholson, and Dr. Charles Platter. I am a better teacher because of you. Special thanks to Dr. Platter and Dr. Nicholson for serving as the committee for my final teaching project. JLSR MMXV 2 Contents Care Lector, .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Livy’s Preface to Ab urbe condita ................................................................................................................ 8 Horatius at the Bridge, II.10 ...................................................................................................................... -

L31 Passage Romulus and Titus Tatius (Uncounted King of Rome

L31 Passage Romulus and Titus Tatius (uncounted king of Rome) are gone Numa Pompilius is made the second king Numa known for peace, religion, and law Temple of Janusdoors open during war, closed during peace; during Numa’s reign, doors were closed L32 Passage Tullus Hostilius becomes third king (mega war) Horatii triplets (Roman) vs. Curiatii (Albans) Two of Horatii are killed immediately; Curiatii are all wounded Final remaining Horatius separates Curiatii and kills them by onebyone Horatius’ sister engaged to one of the Curiatii; weeps when she sees his stuff; Horatius, angry that she doesn’t mourn her own brothers, kills her L33 Passage Tullus Hostilius makes a mistake in a religious sacrifice to Jupiter Jupiter gets angry and strikes his house with a lightning bolt, killing Tullus Ancus Marcius becomes fourth king Ancus Marcius is Numa’s grandson Lucumo (later Lucius Tarquinius Priscus) moves from Etruria to Rome to hold public office at the advice/instigation of Tanaquil While moving, eagle takes his cap and puts it back on Lucumo’s head Tanaquil interprets it as a sign of his future greatness throws Iggy Iggs parties, wins favor becomes guardian of the king’s children upon Ancus’ death L34 Passage Lucius Tarquinius Priscus makes himself fifth king Servius Tullius is a slave in the royal household Tanaquil has a dream that Servius’ head catches on fire She interprets as a sign of greatness LTP makes Servius his adopted son hire deadly shepherd ninjas to go into the palace and assassinate -

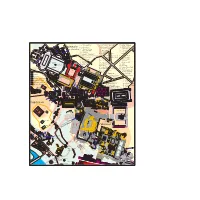

Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence Onto

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2016 Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence onto Urban Topography in the Late Roman Republic, 80-50 BCE Theodore Samuel Rube Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Rube, Theodore Samuel, "Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence onto Urban Topography in the Late Roman Republic, 80-50 BCE" (2016). Honors Theses. 186. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/186 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Searching for Blood in the Streets: Mapping Political Violence onto Urban Topography in the Late Roman Republic, 80-50 BCE An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Classical and Medieval Studies Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Theodore Samuel Rube Lewiston, Maine March 28th, 2016 2 Acknowledgements I want to take this opportunity to express my sincerest gratitude to everybody who during this process has helped me out, cheered me up, cheered me on, distracted me, bothered me, and has made the writing of this thesis eminently more enjoyable for their presence. I am extremely grateful for the guidance, mentoring, and humor of Professor Margaret Imber, who has helped me through every step of this adventure. I’d also like to give a very special thanks to the Bates Student Research Fund, which provided me the opportunity to study Rome’s topography in person. -

Cloaca Maxima Clivus Victoriae Vicus Tuscus

1. Aedes Iovis Optimi 14. Umbilicus Urbis Romae 32. Vicus Tuscus 65 2. T. Iovis Custodis 15. Ara Saturni (Vulcanal) 33. Aedes Castorum Quirinalis 3. Aedes Veiovis 16. Arcus Septimii Severi 34. Aula Domitiani Via Biberatica 4. T. Iunonis Monetae 17. Rostra Vandalica S.Maria Antiqua 5. Aedes Concordiae 18. Lapis Niger 35. T.Augusti (?) 36. Oratorium XL Templum 6. Tabularium 19. Columna Phocae Divi Traiani 7. Aedes Divi Vespasiani 20. Crepido Decennalium Martyrum 8. Porticus Deorum Consentium 21. Crepido statuae Constantii II. 37. Fons Iuturnae 9. Clivus Capitolinus 22. Crepido columnae Arcadio, Honorio 38. Arcus Augusti 10. Aedes Saturni 23. Plutei Traiani 39. Atrium Vestae 63 11. Miliarium Aureum 24. Ficus, olea, vitis 40. T.Vestae 12. Arcus Tiberii 25. Lacus Curtius 41. Aedes Divi Iulii 64 Forum 13. Rostra 26. Columnae honorariae 42. Regia Equus Traiani 27. Doliola 43. Nova Via Traiani 28. Locus statuae Domitiani 44. Horrea Margaritaria Sepulcrum 29. Crepido statuae Constantini 45. Arcus Titi Bibuli T.Martis Ultoris 30. Rostra imperialia 46. T. Iovis Statoris (?) 62 31. Basilica Iulia 47. Thermae Elegabali Res publicaC livu s A 48. T.Elegabali 58. Argiletum Caesar rg en T. 49. T.Veneris et Romae 59. Forum Nervae ta r Minervae Augustus iu 60. Curia s Templum 50. Basilica Maxentii Tiberius usque ad Nervam Veneris 59 Genetricis 55 51. Sepulcrum 61. Forum Iulii Nerva et Trajanus 61 52. T.Romuli 62. Forum Augusti 53. T.Sacrae Urbis 63. Basilica Ulpia Hadrianus usque ad Commodum T.Iani ? Templum 54. T.Antonini et F. 64. Mercatus Traiani III. saec. AD et postea 56 Pacis 55. -

Tacitus, Stoic "Exempla", and the "Praecipuum Munus Annalium"

Swarthmore College Works Classics Faculty Works Classics 10-1-2008 Tacitus, Stoic "Exempla", And The "Praecipuum Munus Annalium" William Turpin Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-classics Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation William Turpin. (2008). "Tacitus, Stoic "Exempla", And The "Praecipuum Munus Annalium"". Classical Antiquity. Volume 27, Issue 2. 359-404. DOI: 10.1525/ca.2008.27.2.359 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-classics/13 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM TURPIN Ta c i t u s , S t o i c exempla,andthepraecipuum munus annalium Tacitus’ claim that history should inspire good deeds and deter bad ones (Annals 3.65) should be taken seriously: his exempla are supposed to help his readers think through their own moral difficulties. This approach to history is found in historians with clear connections to Stoicism, and in Stoic philosophers like Seneca. It is no coincidence that Tacitus is particularly interested in the behavior of Stoics like Thrasea Paetus, Barea Soranus, and Seneca himself. They, and even non-Stoic characters like Epicharis and Petronius, exemplify the behavior necessary if Roman freedom was to survive the monarchy. Exsequi sententias haud institui nisi insignes per honestum aut notabili dedecore, quod praecipuum munus annalium reor, ne virtutes sileantur utque pravis dictis factisque ex posteritate et infamia metus sit. Tac. Ann. 3.65.11 The claim that history should inspire good deeds and deter bad ones has often been seen as purely conventional; scholars like Bessie Walker and Ronald Syme saw Tacitus as more interested in hard-nosed analysis, and dismissed his remark as a mere relic of tradition.2 But T. -

Rome's Holy Mountain: the Capitoline Hill in Late Antiquity

CJ-Online, 2019.04.04 BOOK REVIEW Rome’s Holy Mountain: The Capitoline Hill in Late Antiquity. By JASON MORALEE. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018. Pp. xxv + 278. Hardcover, $74.00. ISBN 978-0-19-049227-4. rom the marble plan of Septimius Severus (the Forma Urbis) to the De- scriptio Urbis Romae of Leon Battista Alberti, the centrality of the Capito- line hill has always been apparent. When the medieval stairway of the Ar- acoeliF was constructed, that “holy mountain” received the marble blocks from a huge temple located on the Quirinal hill; in the late 19th century it was imagined as the Mons Olympus by Giuseppe Sacconi, the architect of the Monument to King Victor Emmanuel II (in its turn compared to the sanctuary at Praeneste). Moralee’s book tackles a long, yet too often neglected, period in the Capitoline’s history – ‘from the third to the seventh centuries CE’ (or, for the sake of preci- sion, ‘from 180 to 741’) – and his investigations successfully dig into countless and poorly known literary sources, bringing to life forgotten people, monuments and stories. These are spread into seven chapters that examine different ways to experience the Capitoline, such as climbing, living and working, worshipping, remembering and destructing. In short, Moralee’s goal is to write ‘a history of the people who used the Capitoline Hill in late antiquity … and wrote about the hill’s variegated past’ (xviii). The ancient distinction between mons and collis would have deserved a brief discussion; in any case, the Capitolium was a mons and a very important one from a religious point of view – hence Moralee’s “holy mountain.” In antiquity the word Capitolium could indicate the southern summit of the hill (as opposed to the Arx) or imply the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. -

THE ROMAN ARMY's EMERGENCE from ITS ITALIAN ORIGINS Patrick Alan Kent a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Universit

THE ROMAN ARMY’S EMERGENCE FROM ITS ITALIAN ORIGINS Patrick Alan Kent A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Richard Talbert Nathan Rosenstein Daniel Gargola Fred Naiden Wayne Lee ABSTRACT PATRICK ALAN KENT: The Roman Army’s Emergence from its Italian Origins (Under the direction of Prof. Richard Talbert) Roman armies in the 4 th century and earlier resembled other Italian armies of the day. By using what limited sources are available concerning early Italian warfare, it is possible to reinterpret the history of the Republic through the changing relationship of the Romans and their Italian allies. An important aspect of early Italian warfare was military cooperation, facilitated by overlapping bonds of formal and informal relationships between communities and individuals. However, there was little in the way of organized allied contingents. Over the 3 rd century and culminating in the Second Punic War, the Romans organized their Italian allies into large conglomerate units that were placed under Roman officers. At the same time, the Romans generally took more direct control of the military resources of their allies as idea of military obligation developed. The integration and subordination of the Italians under increasing Roman domination fundamentally altered their relationships. In the 2 nd century the result was a growing feeling of discontent among the Italians with their position. Indeed, the vital military role of the Italians was reinforced by the somewhat limited use made of non-Italians in Roman armies. -

Excellence Redefined: the Evolution of Virtus in Ancient Rome

Excellence Redefined: The Evolution of Virtus in Ancient Rome A thesis submitted to Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Emily J. Trygstad May 2010 Oxford, Ohio i Abstract While there has been extensive academic research for over a thousand years in the field of Classics, it is impressive to note just how much research still needs to be done. For my thesis, I plan to take some of my own personal academic interest and channel it into a largely understudied topic: the evolution of the Roman value of virtus, and the effects that this change produced in Roman society. Virtus, which was in many ways held to be the paramount quality an ancient Roman male could possess, was initially expressed through an assertion of martial prowess. No simple translation for this ideal exists, however; “bravery” or “manliness”, while sometimes used, do not fully render the complex importance of virtus. Historian Myles McDonnell sums the notion up best: “the relationship... between virtus and all the other things the Romans valued – liberty, property, family, and fatherland – is one of dependence. Virtus embraces all that is good because it is virtus that guards and preserves all that is good” (McDonnell, 32). Over the course of time, however, history sees virtus make a gradual shift as an ideal manifested through military distinction to a more liberal celebration of “excellence”, not dissimilar from the Greek notion of‟αρετή. While most classicists and historians alike seem to agree that the ideal did indeed evolve over time, the study of what caused this shift has only barely been explored.