Racial History Surrounding the Lynchings in Duluth, MN Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Studies Journal 2013

Blending Gender: Colorado Denver University of The Flapper, Gender Roles & the 1920s “New Woman” Desperate Letters: Abortion History and Michael Beshoar, M.D. Confessors and Martyrs: Rituals in Salem’s Witch Hunt The Historic American StudiesHistorical Journal Building Survey: Historical Preservation of the Built Arts Another Face in the Crowd Commemorating Lynchings Studies Manufacturing Terror: Samuel Parris’ Exploitation of the Salem Witch Trials Journal The Whigs and the Mexican War Spring 2013 . Volume 30 Spring 2013 Spring . Volume 30 Volume Historical Studies Journal Spring 2013 . Volume 30 EDITOR: Craig Leavitt PHOTO EDITOR: Nicholas Wharton EDITORIAL STAFF: Nicholas Wharton, Graduate Student Jasmine Armstrong Graduate Student Abigail Sanocki, Graduate Student Kevin Smith, Student Thomas J. Noel, Faculty Advisor DESIGNER: Shannon Fluckey Integrated Marketing & Communications Auraria Higher Education Center Department of History University of Colorado Denver Marjorie Levine-Clark, Ph.D., Thomas J. Noel, Ph.D. Department Chair American West, Art & Architecture, Modern Britain, European Women Public History & Preservation, Colorado and Gender, Medicine and Health Carl Pletsch, Ph.D. Christopher Agee, Ph.D. Intellectual History (European and 20th Century U.S., Urban History, American), Modern Europe Social Movements, Crime and Policing Myra Rich, Ph.D. Ryan Crewe, Ph.D. U.S. Colonial, U.S. Early National, Latin America, Colonial Mexico, Women and Gender, Immigration Transpacific History Alison Shah, Ph.D. James E. Fell, Jr., Ph.D. South Asia, Islamic World, American West, Civil War, History and Heritage, Cultural Memory Environmental, Film History Richard Smith, Ph.D. Gabriel Finkelstein, Ph.D. Ancient, Medieval, Modern Europe, Germany, Early Modern Europe, Britain History of Science, Exploration Chris Sundberg, M.A. -

Duluth Lynchings Newspaper Index for the Duluth News Tribune

Duluth Lynchings Newspaper Index for the Duluth News Tribune June 17, 1920 through September 20, 1920 Index created by Heather Hawkins, volunteer, December 2002. Minnesota Historical Society z 345 Kellogg Blvd. West z St. Paul, Minnesota 55102-1906 1 Date Newspaper Article Name Page(s) Comments 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Duluth's Disgrace 1 editorial 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Superior Police to Deport Idle Negroes at Once 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune 3 Dragged from Jail and Hanged at Street Corner 1,3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Lynchers Will Be Prosectured By Att'y Greene 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune 4-Hour Battle Waged By Mob to Get Victims 1,3 Long 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Attack on Girl Was Cause of Negro Lynching 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Negros Nabbed at Virginia Sent to Saint Paul 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Opposes Mob 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Attorney Hugh M'Clearn Attempts to Stay Mob 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Woman Curses Police for Failure to Save Negroes 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Chief Murphy Promises a Thorough Investigation 3 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Demand Quiz of Police Efforts to Defeat Mob 1,8 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Aftermath of Lynching Orgy 1 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Militiamen Kept on Duty to Help Maintain Order 1,9 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Damage to Police Headquarters by Mob Over $2,000 1 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Officials Will Act After Quiz of Mob Leaders 1,9 Long 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Guardsmen Sent to Virginia For Negro Suspects -

The Lynchings in Duluth : Second Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LYNCHINGS IN DULUTH : SECOND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Fedo | 224 pages | 15 Feb 2016 | Minnesota Historical Society Press | 9781681340135 | English | none The Lynchings in Duluth : Second Edition PDF Book There are some liberties taken with the docudrama; it's presented in a radio bulletin format, and Duluth didn't have a radio station in , Fedo noted. Melissa Taylor first saw the postcard when she was in high school. Read, 53, an associate high school principal, lived across the country in Kingston, Wash. Create An Account. As the camera flashed, some stared impassively; others grinned and slapped each other on the shoulders, stretching their necks and cocking their heads to make sure they got in the picture. Boyte incites readers to join today's "citizen movement," offering practical tools for how we can change the face of America by focusing on issues close to home. It was front-page news for the Duluth, Minn. Cloud State graduate, mixed and mastered the program, according to the university. He served about a year in state prison. Warren Read is the great-grandson of Louis Dondino, who was involved in the lynching of Black men in Boyte incites readers to join today's "citizen Together, they planted an oak tree near the grave sites of Clayton, Jackson and McGhie in Duluth in June for the anniversary of the lynchings. Miller was acquitted , but Mason was convicted and sentenced to serve seven to thirty years in prison. Christmas in Minnesota: A celebration in memories, stories,. The Lynchings in Duluth is a powerful reminder of the broader American pattern. -

Resource List

RESOURCE LIST Resources for Option A (the lynchings, Max Mason trial, and Max Mason pardon) 1. Who’s Who document 2. Video of Jerry Blackwell introducing the history of the Duluth lynchings, which includes CBS Minnesota/WCCO media clip: “Minnesota’s First Posthumous Pardon Granted to Black Man, Max Mason, Convicted in Century-Old Duluth Case” 3. Article: “On June 15, 1920, a Duluth mob lynched three black men,” by Tina Burnside | July 29, 2019 minnpost.com/mnopedia/2019/07/on-june-15-1920-a-duluth-mob-lynched-three-black- men/?gclid=CjwKCAiAl4WABhAJEiwATUnEFwBcpXPeqsMV8xeego8BBv7b33cnpJOQnLAEEc8vUr wb0IY2mv-8PhoClMUQAvD_BwE 4. Article: “Centennial remembrance of Duluth lynchings subdued - but hopeful,” by Dan Kraker | June 15, 2020 https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/06/15/centennial-remembrance-of-duluth-lynchings- subdued-but-hopeful 5. Video: “Minnesota governor marks 100th anniversary of Duluth lynching” | Nation Jun 15, 2020 pbs.org/newshour/nation/watch-minnesota-governor-marks-100th-anniversary-of-duluth- lynching 6. History Center information regarding the lynchings, legal proceedings, and incarcerations https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/lynchings.php https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/legal.php https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/incarcerations.php 7. Max Mason pardon application, letters in support and the pardon certificate. 8. Max Mason pardon hearing 9. Article: “Minn. grants state’s first posthumous pardon to Max Mason, in case related to Duluth lynchings,” by Dan Kraker | June 12, 2020 https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/06/12/minn-grants-states-first-posthumous-pardon-to- max-mason 10. Article: “Century after Minnesota lynchings, black man convicted of rape ‘because of his race’ up for pardon,” by Meagan Flynn | June 12, 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/12/duluth-lynchings-mason-pardon/ 11. -

America Without the Death Penalty

................................ America without the Death Penalty .................................. America without the Death Penalty States Leading John F. Galliher the Way Larry W. Koch David Patrick Keys Teresa J. Guess Northeastern University Press Boston published by university press of new england hanover and london To Hugo Adam Bedau Northeastern University Press Published by University Press of New England One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com ᭧ 2002 by John F. Galliher First Northeastern University Press/UPNE paperback edition 2005 Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. ISBN for the paperback edition 1–55553–639–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data America without the death penalty : states leading the way / John F. Galliher . [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–55553–529–1 (cloth : alk. paper) Capital punishment—United States—States. I. Galliher, John F. HV8699.U5 G35 2002 364.66Ј0973—dc21 2002004923 -

Thesis Pdf (252.5Kb)

The Duluth Lynching By: Angie Nelson History 489 Dr. Kate Lang Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Chapter 1 Introduction Racial Conflict across the Nation There have been decades of violence following the civil war; the early twentieth century continued that trend. The power and control lust of the white mob and the use of lynching has been a tradition for over a hundred years. Not one state is free from blame, each state has its own stained past and record of lynching. In the Midwest the lynching numbers are lower. Between 1882 and 1962, Minnesota had nine recorded lynchings, Wisconsin had six recorded lynchings, and Illinois had thirty-four recorded lynchings.1 Although states like Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas have recorded lynchings numbering over two hundred, the north contributed to the nation‟s theme of discrimination. In fact lynching was such a trend across the United States that between 1882 and1962, 4,736 lynchings have been recorded.2 Lynchings were happening across the United States for a number of reasons but mostly to intimidate blacks into political, social, and economic submission. About 25 % of lynch victims were lynched because they were accused of rape or attempted rape. “Most blacks were lynched for outspokenness or other presumed offenses against whites, or in the aftermath of race riots. In many cases lynchings were not spontaneous mob 1“Lynching by State and Race 1882-1962” Online at: http://www.nathanielturner.com/lynchingbystateandrace.htm, visited on: 09/18/2006 2“The History of Jim Crow” Online at: http://www.jimcrowhistory.org/geography/violence.htm visited on: 09/18/2006 violence but involved a degree of planning and law-enforcement cooperation.”3 What did the United States‟ legal system do about the crimes against blacks? Today the United States has laws against lynching by state, but these laws were not always in place and were late in coming. -

The NAACP's Rape Docket and the Origins of Criminal Procedure

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA JOURNAL OF LAW ANDSOCIAL CHANGE Volume 24, Number 3 2021 THE NAACP’S RAPE DOCKET AND THE ORIGINS OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE BY SCOTT W. STERN* Abstract. This Article provides the definitive account of the surprisingly voluminous docket of rape cases argued by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It argues, for the first time, that the NAACP’s rape docket was central to the development of modern criminal procedure—to the establishment of the right to counsel, the right to remain silent, the right to a trial free from mob violence or influence, the right against self-incrimination via a coerced confession, and the right to a jury of one’s peers selected without discrimination. Drawing on original archival research, this Article demonstrates that all of these rights have their origins in the hundreds of cases argued by the NAACP on behalf of Black men accused of sexual assault by white women. This Article also argues that these cases were central to the development of the NAACP’s legal department, the relationships between local branches and the national office, and the careers of the famous civil rights attorneys—from Charles Hamilton Houston to Jack Greenberg—who rose to national prominence with the NAACP. Thus, these cases were central to the development of civil rights litigation itself. Indeed, the first significant Supreme Court case argued for the NAACP by a Black attorney was an interracial rape case. The first Supreme Court case ever argued by a Black woman, Constance Baker Motley, was an interracial rape case. -

To Kill a Mockingbird Pathfinder Ideas for Research REQUIRED Databases for Research

To Kill a Mockingbird Pathfinder Ideas for Research Civilian Conservation Corps & New Deal Harper Lee Civil Rights Jim Crow Laws Duluth Lynchings Ku Klux Klan Dust Bowl Prohibition Eleanor & Franklin Delano Roosevelt Scottsboro Boys Trial The Great Depression Stock Market Crash of 1929 REQUIRED databases for research: Britannica Online Academic Gale - Discovering Collection Be sure to print off your sources. Additional websites for research: Information about the Civilian Conservation Corps and New Deal: The New Deal from the National Archives Links to web sites relating to the New Deal era for research on New Deal agriculture, labor, and arts programs. Information about Civil Rights: African-American Resources on the Internet Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement NAACP Documenting the American South – primary sources from the University of North Carolina Information about the Duluth Lynchings: Duluth News Tribune/Newsbank Minneapolis Star Tribune/Newsbank This collection of Duluth News Tribune articles is located with the Duluth Public Library databases. The password is on the gold tag taped to your computer. Sort by oldest date first. Search Duluth Lynchings or Clayton, Jackson, McGhie Memorial Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial – Official Site Minnesota Historical Society – Duluth Lynching Information about the Dust Bowl: American Memory—Library of Congress—Voices from the Dust Bowl The Dust Bowl—PBS Information about Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum Information about The Great Depression: Timeline of the Great Depression Information about Harper Lee: Biography In Context This Duluth Public Library database has great biographic articles that come from reference books. -

The Great Migration Resource Title: the Great Migration, Godfathers and Sons

Teacher’s Guide Rondo Trunk Grade 6 Dear 6th Grade Educator, Greetings! First off we are excited that you have checked out the Rondo 6th Grade Trunk. We were passionate about putting this trunk together, comprising stories that often go untold, and using the Common Core Standards and the GANAG format to complete this project. Our hope that this trunk experience aids both you and your class in learning and understanding more about how migration and immigration have impacted Minnesota society, especially the Rondo neighborhood. We also want to express that the lesson plans are full! They are full of exciting activities, options for multi-modal learning and GANAG strategies that will assist you in reaching all of your students! We purposely did this so that you can be an instructional leader and have options for success in your classroom. We also want to challenge you take time to review the lesson plans, look at the options provided for lesson planning and read the background information provided in the additional resource sections and literature provided. In addition, members of the community have agreed to volunteer their time to assist in making your lesson plans come to life. Please contact your prospective speaker(s) at least two weeks in advance of the lesson. Our sincere hope is that you and your class enjoy these lesson plans just as much as we enjoyed putting them together. Sincerely, Alecia Mobley and Rebecca Wade Potential Speakers for Rondo Trunk Project Individuals also featured in Voices of Rondo. 1. Mr. Nathaniel Kahliq Phone: (651) 335-0743 Email: [email protected] • Born and Raised at 304 Rondo • Grandfather was Rev. -

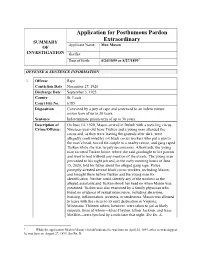

Application for Posthumous Pardon Extraordinary [Matter No

Application for Posthumous Pardon SUMMARY Extraordinary Applicant Name: Max Mason OF INVESTIGATION aka/fka: Date of Birth: 4/24/1899 or 8/27/18991 OFFENSE & SENTENCE INFORMATION 1. Offense Rape Conviction Date November 27, 1920 Discharge Date September 3, 1925 County St. Louis Court File No. 6785 Disposition Convicted by a jury of rape and sentenced to an indeterminate prison term of up to 30 years. Sentence Indeterminate prison term of up to 30 years. Description of On June 14, 1920, Mason arrived in Duluth with a traveling circus. Crime/Offense: Nineteen-year-old Irene Tusken and a young man attended the circus and, as they were leaving the grounds after dark, were allegedly confronted by six black circus workers who put a gun to the man’s head, forced the couple to a nearby ravine, and gang raped Tusken while she was largely unconscious. Afterwards, the young man escorted Tusken home, where she said goodnight to her parents and went to bed without any mention of the events. The young man proceeded to his night job and, in the early morning hours of June 15, 2020, told his father about the alleged gang rape. Police promptly arrested several black circus workers, including Mason, and brought them before Tusken and the young man for identification. Neither could identify any of the workers as the alleged assailants and Tusken shook her head no when Mason was presented. Tusken was also examined by a family physician who found no evidence of sexual intercourse, including abrasions, bruising, inflammation, soreness, or tenderness. Mason was allowed to leave with the circus to its next destination in Virginia, Minnesota. -

Midamerica XXXIX 2012

MidAmerica XXXIX The Yearbook of the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature DAVID D. ANDERSON, FOUNDING EDITOR MARCIA NOE, EDITOR The Midwestern Press The Center for the Study of Midwestern Literature and Culture Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1033 2012 Copyright 2012 by the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this work may be reproduced without permission of the publisher MidAmerica 2012 (0190-2911) is a peer-reviewed journal that is published annually by the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature. This journal is a member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF MIDWESTERN LITERATURE http://www.ssml.org/home EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Marcia Noe, Editor, The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Marilyn Judith Atlas Ohio University William Barillas University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Robert Beasecker Grand Valley State University Roger Bresnahan Michigan State University Robert Dunne Central Connecticut State University Scott D. Emmert University of Wisconsin-Fox Valley Philip Greasley University of Kentucky Sara Kosiba Troy University Nancy McKinney Illinois State University Mary DeJong Obuchowski Central Michigan University Ronald Primeau Central Michigan University James Seaton Michigan State University Jeffrey Swenson Hiram College EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Kaitlin Cottle Gale Mauk Rachel Davis Jeffrey Melnik Laura Duncan Heather Palmer Christina Gaines Mollee Shannon Blake Harris Meghann Tarry Michael Jaynes MidAmerica, a peer-reviewed journal of the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature, is published annually. We welcome scholarly contri- butions from our members on any aspect of Midwestern literature and cul- ture. -

Status of Women in State Social Studies Standards

Where are the Wo men? www.WomensHistory.org A Report on the Status of Women in the United States Social Studies Standards Report By: Elizabeth L. Maurer, Director of Program Jeanette Patrick, Project Director Liesle M. Britto, Editorial Assistant Henry Millar, Editorial Assistant Museum Advisory Council Dr. Catherine Allgor, Chair Nancy Hayward Massachusetts Historical Society Former Director of School Programs George Washington’s Mount Vernon Dr. Franky Abbott The Digital Public Library Fath Davis Ruffin Smithsonian National Museum of American Dr. Carol Berkin History Baruch College, The City University of New York Dr. Katrin Schultheiss Audrey Davis George Washington University Alexandria Black History Museum Dr. Marjorie Spruill Dr. Julie Des Jardins University of South Carolina Independent Scholar Jennifer Thomas Dr. Laura Edwards Virginia Association of Museums Duke University Jill Tietjen Dr. Cathy Gorn Former Director National History Day National Women’s Hall of Fame Kristina Graves Dr. William White Clayton County Public Schools Retired Director of Educational Program Development Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Where are the Women? A Report on the Status of Women in the United States Curricula. Copyright © 2017 by National Women’s History Museum. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this report may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission by the copyright owner. The National Women’s History Museum would like to give special thanks to all the Charter Members whose generous tax-deductible gifts made the research for this report possible and enable the organization to continue its important work bringing women’s history into the light of day.