A New Era in U.S.-Vietnam Relations: Deepening Ties Two Decades After

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market Via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation

CHAPTER 7 Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation Phi Vinh Tuong This chapter should be cited as: Phi, Vinh Tuong, 2012. “Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation.” In Five Triangle Areas in The Greater Mekong Subregion, edited by Masami Ishida, BRC Research Report No.11, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. CHAPTER 7 DEVELOPING WEST-NORTHEN PROVINCES OF VIETNAM: CHALLENGE TO INTEGRATE WITH GMS MARKET VIA CHINA-LAOS-VIETNAM TRIANGLE COOPERATION Phi Vinh Tuong INTRODUCTION The economy of Vietnam has benefited from regional and world markets over the past 20 years of integration. Increasing trade promoted investment, job creation and poverty reduction, but the distribution of trade benefits was not equal across regions. Some remote and mountainous areas, such as the west-northern region of Vietnam, were left at the margin. Even though they are important to the development of Vietnam, providing energy for industrialization, the lack of resource allocation hinders infrastructure development and, therefore, reduces their chances of access to regional and world markets. The initiative of developing one of the northern triangles, which consists of three west-northern provinces of Vietnam, the northern provinces of Laos and a southern part of Yunnan Province in China (we call the northern triangle as CHLV Triangle hereafter), could be a new approach for this region’s development. Strengthening the cooperation and specialization among these provinces may increase the chances of exporting local products with higher value added to regional markets, including the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) and south-western Chinese markets. -

2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid IUPAC (2,4-dichlorophenoxy)acetic acid name 2,4-D Other hedonal names trinoxol Identifiers CAS [94-75-7] number SMILES OC(COC1=CC=C(Cl)C=C1Cl)=O ChemSpider 1441 ID Properties Molecular C H Cl O formula 8 6 2 3 Molar mass 221.04 g mol−1 Appearance white to yellow powder Melting point 140.5 °C (413.5 K) Boiling 160 °C (0.4 mm Hg) point Solubility in 900 mg/L (25 °C) water Related compounds Related 2,4,5-T, Dichlorprop compounds Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) is a common systemic herbicide used in the control of broadleaf weeds. It is the most widely used herbicide in the world, and the third most commonly used in North America.[1] 2,4-D is also an important synthetic auxin, often used in laboratories for plant research and as a supplement in plant cell culture media such as MS medium. History 2,4-D was developed during World War II by a British team at Rothamsted Experimental Station, under the leadership of Judah Hirsch Quastel, aiming to increase crop yields for a nation at war.[citation needed] When it was commercially released in 1946, it became the first successful selective herbicide and allowed for greatly enhanced weed control in wheat, maize (corn), rice, and similar cereal grass crop, because it only kills dicots, leaving behind monocots. Mechanism of herbicide action 2,4-D is a synthetic auxin, which is a class of plant growth regulators. -

Joint Evaluation of Support to Anti-Corruption Efforts Viet Nam Country Report

Evaluation Department Joint Evaluation of Support to Anti-Corruption Efforts Viet Nam Country Report Report 6/2011 – Study SADEV SWEDISH AGENCY FOR DEVELOPMENT EVALUATION Norad Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation P.O.Box 8034 Dep, NO-0030 Oslo Ruseløkkveien 26, Oslo, Norway Phone: +47 22 24 20 30 Fax: +47 22 24 20 31 Photo: Ken Opprann Design: Agendum See Design Print: 07 Xpress AS, Oslo ISBN: 978-82-7548-602-6 Joint Evaluation of Support to Anti-Corruption Efforts Viet Nam Country Report June 2011 Submitted by ITAD in association with LDP Responsibility for the contents and presentation of findings and recommendations rest with the evaluation team. The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily correspond with those of Norad. Preface Donor agencies have increasingly included the fight against corruption in their over- all governance agenda. In preparation for this evaluation, a literature review1 was undertaken which showed that our support for anti-corruption work has sometimes had disappointing results. Has the donors’ approach to anti-corruption work been adapted to circumstances in the countries? What are the results of support for combating different types of cor- ruption, including forms that affect poor people and women in particular? These were some of the overarching questions that this evaluation sought to answer. The evaluation provides insights for the debate, drawing on recent evidence from five countries. The main conclusions and recommendations are presented in the synthesis report. In addition, separate reports have been prepared for each of the case countries Bangladesh, Nicaragua, Tanzania, Viet Nam and Zambia. -

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Teacher Resource Packet for Vietnamese Students. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia

)xocliMENTRESUME ,ED 118 679 UD 015 707 TITLE- Teacher Resource Packet for Vietnamese Students. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia. PUB DATE Jul 75 NOTE'-. litp.; This document is available in microfiche only 'due to the print size of parts of the original 0 document EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Asian Americans; Bilingual Education; *Bilingual Students; Educational. Resources; Elementary School Students; English (Second Language); *Ethnic Groups;, Guidelines; Immigrants; *Indo hinese; Minority Group Children; Minority Groups; *Re ugees; Resource Guides; Resource Materials; Se ndary School Students; *Student Characterist cs;- Student Needs; Student Problems; Student TeacheRelationship; Teacher Guidance; Teacher Respons bility IDENTIFIERS *Vietnam r ABSTRACT This packet provides information for classroom , teachers who will be working with Vietnamese students Among the subject matter discussed in the history and general in ormation section are the Republic of Vietnam, family loyalty, p ofessional man, politeness and restraint, village life, fruits and vegetables, meat dishes, festivals, and religion. Other sections include a summary of some cultural differences, a Vietnamese language guide, and Asian immigrant impressions. A section on bilingual education information discus es theory, definition, and the legal situation concerning bilingu4lism and English as a second language. Suggestions for interacting with non-English dominant students in all grade levels in either a regular classroom setting or a secondary school setting are provided. Relevant resources, such as materials that can be used for basic instruction in English (as a second language) classes, reading resources, and community resources are enclosed. (Author/AM) **********L********************************************************* Documents acquired by ERIlinclude many informal unpublished * materials not aotailable from ther sources. -

Vietnam's National Capacity Needs Self-Assessment for Global Environmental Management

MONRE Vietnam’s National Capacity Needs Self-Assessment for Global Environmental Management NATIONAL REPORT Prepared by: Viet Nam NCSA Team Department of Environment Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Hanoi, June 2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENT Page LIST OF FIGURE................................................................................................ 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................. 7 PART I: INTRODUCTION – GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT CONTEXT AND THE NATIONAL CAPACITY SELF-ASSESSMENT (NCSA) PROCESS IN VIETNAM .................................................................................................................. 10 1 Global environmental issues .............................................................................. 10 2 National Capacity Self Assessment Process and Project in Vietnam .................... 10 2.1 Project objectives ...................................................................................... 10 2.2 Implementation arrangement .................................................................. 11 2.3 NCSA implementation process in Viet Nam ........................................ 12 2.4 Major Stakeholders ..................................................................................... 13 2.5 Monitoring Arrangements ........................................................................... 13 PART II: ENVIRONMENTAL SCENARIO, LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS -

The SRAO Story by Sue Behrens

The SRAO Story By Sue Behrens 1986 Dissemination of this work is made possible by the American Red Cross Overseas Association April 2015 For Hannah, Virginia and Lucinda CONTENTS Foreword iii Acknowledgements vi Contributors vii Abbreviations viii Prologue Page One PART ONE KOREA: 1953 - 1954 Page 1 1955 - 1960 33 1961 - 1967 60 1968 - 1973 78 PART TWO EUROPE: 1954 - 1960 98 1961 - 1967 132 PART THREE VIETNAM: 1965 - 1968 155 1969 - 1972 197 Map of South Vietnam List of SRAO Supervisors List of Helpmate Chapters Behrens iii FOREWORD In May of 1981 a group of women gathered in Washington D.C. for a "Grand Reunion". They came together to do what people do at reunions - to renew old friendships, to reminisce, to laugh, to look at old photos of them selves when they were younger, to sing "inside" songs, to get dressed up for a reception and to have a banquet with a speaker. In this case, the speaker was General William Westmoreland, and before the banquet, in the afternoon, the group had gone to Arlington National Cemetery to place a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. They represented 1,600 women who had served (some in the 50's, some in the 60's and some in the 70's) in an American Red Cross program which provided recreation for U.S. servicemen on duty in Europe, Korea and Vietnam. It was named Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas (SRAO). In Europe it was known as the Red Cross center program. In Korea and Vietnam it was Red Cross clubmobile service. -

Vietnam Maximizing Finance for Development in the Energy Sector

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized VIETNAM MAXIMIZING FINANCE FOR DEVELOPMENT IN THE ENERGY SECTOR DECEMBER 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by a core team led by Franz Gerner (Lead Energy Specialist, Task Team Leader) and Mark Giblett (Senior Infrastructure Finance Specialist, Co-Task Team Leader). The team included Alwaleed Alatabani (Lead Financial Sector Specialist), Oliver Behrend (Principal Investment Officer, IFC), Sebastian Eckardt (Lead Country Economist), Vivien Foster (Lead Economist), and David Santley (Senior Petroleum Specialist). Valuable inputs were provided by Pedro Antmann (Lead Energy Specialist), Ludovic Delplanque (Program Officer), Nathan Engle (Senior Climate Change Specialist), Hang Thi Thu Tran (Investment Officer, IFC), Tim Histed (Senior Business Development Officer, MIGA), Hoa Nguyen Thi Quynh (Financial Management Consultant), Towfiqua Hoque (Senior Infrastructure Finance Specialist), Hung Tan Tran (Senior Energy Specialist), Hung Tien Van (Senior Energy Specialist), Kai Kaiser (Senior Economist), Ketut Kusuma (Senior Financial Sector Specialist, IFC), Ky Hong Tran (Senior Energy Specialist), Alice Laidlaw (Principal Investment Officer, IFC), Mai Thi Phuong Tran (Senior Financial Management Specialist), Peter Meier (Energy Economist, Consultant), Aris Panou (Counsel), Alejandro Perez (Senior Investment Officer, IFC), Razvan Purcaru (Senior Infrastructure Finance Specialist), Madhu Raghunath (Program Leader), Thi Ba -

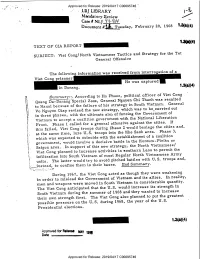

Prisoner Intelligence, Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Tactics and Strategy

Approved for Release: 2019/04/17 C00095746 . .LBj_ LIBRARY 1.9, M"“’“‘°"' R°"‘°“’ ‘ " ' an . i Case#NLji WNW Document February 20, 1968 1-3(8)“) "W" TEXT or cm REPORT i and Strategy for the Tet SUBJECT: Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Tactics General Offensive interr of a The fo information was received Viet C0 oner He was captured in Danang. 1-3<e><~> I Viet Cong According to Ho Phuoc, political officer of #2 ;§_u_zl_nmary:_»:,_ General Nguyen Chi Thanh was recalled ¢ Quang Da-Danang Special Zone, la strategy in South Vietnam. General to Hanoi because of the failure of his -_ which was to bemcarried out \ V0 Nguyen Giap revised the new strategy, u-‘.111. with the ultimate aim of forcing the Government of _,.,.__~._ in three phases, with the National Liberation Vietnam to accept, a coalition government "the cities. If "" called for a general offensive against . Front. Phase 1 cities and, -ff‘ the Viet Cong’ troops during Phase 2 would besiege ... this failed, Phase 3, lure U. S. troops into the Khe Sanh area. i at the same time, a coalition which was expected to coincide with the establishment of Kontum-Pleiku or .... government, would involve a decisive battle in the .,..~.---,--~v_,-.-"1",-_" North Vietnamesel Saigon area. In support of this new strategy, the _ southern Laos to permit the Viet Cong planned to increase activities in Vietnamese Army into South Vietnam of most Regular North ~. infiltration and pitched battles with U. S. troops O units. The latter would try to avoid A 1 them in their bases. -

Vietnam Business: Vietnam Development Report 2006 Report Business: Development Vietnam Vietnam Report No

Report No. 34474-VNReport No. Vietnam 34474-VN Vietnam Development Business: Report 2006 Vietnam Business Vietnam Development Report 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized November 30, 2005 Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit East Asia and Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized IMF International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation JSB Joint Stock Bank JSC Joint Stock Company LDIF Local Development Investment Fund LEFASO Vietnam Leather and Footwear Association LUC Land-Use Right Certificate MARD Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development MDG Millennium Development Goal MOC Ministry of Construction MOET Ministry of Education and Training MOF Ministry of Finance MOH Ministry of Health MOHA Ministry of Home Affairs MOI Ministry of Industry MOLISA Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs MONRE Ministry ofNatural Resources and the Environment MOT Ministry of Transport MPDF Mekong Private Sector Development Facility MPI Ministry of Planning and Investment NBIC National Business Information Center NGO Non-Governmental Organization NOIP National Office for Intellectual Property NPL Non-Performing Loan NPV Net Present Value ODA Official Development Assistance OOG Office of Government OSS One-Stop Shop PCF People’s Credit Fund PCI Provincial Competitiveness Index PER-IFA Public Expenditure Review-Integrated -

History of Seed in the U.S. the Untold American Revolution 660 Pennsylvania Ave SE Suite 302 Washington, D.C

History of Seed in the U.S. The Untold American Revolution 660 Pennsylvania Ave SE Suite 302 Washington, D.C. 20003 P (202) 547-9359 F (202) 547-9429 www.centerforfoodsafety.org Save Our Seeds An exhibition at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., What’s Cooking Uncle Sam?, traces the history of U.S. agriculture from “the horse and plow (SOS) to today’s mechanized farm.” While the exhibition contains humorous elements, including a corporate campaign to win the War Food A program of the Administration’s endorsement of its Vitamin Donuts—“For pep and vigor… Center for Food Safety Vitamin Donuts!”—it also chronicles a sobering story of American farming and how the effects of U.S. food and agricultural policies reach far beyond the borders of Uncle Sam. Throughout, it is clear that the path of agriculture begins with the seed. Over the past 40 years, the U.S. has led a radical shift toward commercialization, consolidation, and control of seed. Prior to the advent of industrial agriculture, there were thousands of seed companies and public breeding institutions. At present, the top 10 seed and chemical companies, with the majority stake owned by U.S. corporations, control 73 1 Debbie Barker percent of the global market. International Program Today, fewer than 2 percent of Americans are farmers,2 whereas 90 percent 3 Director of our citizens lived on farms in 1810. This represents perhaps a more transformative revolution than even the Revolutionary War recorded in our history books. August 2012 This report will provide a summary of U.S. -

University of California Santa Cruz the Vietnamese Đàn

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE VIETNAMESE ĐÀN BẦU: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT IN DIASPORA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by LISA BEEBE June 2017 The dissertation of Lisa Beebe is approved: _________________________________________________ Professor Tanya Merchant, Chair _________________________________________________ Professor Dard Neuman _________________________________________________ Jason Gibbs, PhD _____________________________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter One. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Geography: Vietnam ............................................................................................................................. 6 Historical and Political Context .................................................................................................... 10 Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 17 Vietnamese Scholarship .............................................................................................................. 17 English Language Literature on Vietnamese Music