George Frideric Handel's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Early Music Festival Announces 2013 Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 1, 2012 CONTACT: Kathleen Fay, Executive Director | Boston Early Music Festival 161 First Street, Suite 202 | Cambridge, MA 02142 617-661-1812 | [email protected] | www.bemf.org BOSTON EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2013 FESTIVAL OPERATIC CENTERPIECE , HANDEL ’S ALMIRA Cambridge, MA – April 1, 2012 – The Boston Early Music Festival has announced plans for the 2013 Festival fully-staged Operatic Centerpiece Almira, the first opera by the celebrated and beloved Baroque composer, George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), in its first modern-day historically-conceived production. Written when he was only 19, Almira tells a story of intrigue and romance in the court of the Queen of Castile, in a dazzling parade of entertainment and delight which Handel would often borrow from during his later career. One of the world’s leading Handel scholars, Professor Ellen T. Harris of MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), has said that BEMF is the “perfect and only” organization to take on Handel’s earliest operatic masterpiece, as it requires BEMF’s unique collection of artistic talents: the musical leadership, precision, and expertise of BEMF Artistic Directors Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs; the stimulating and informed stage direction and magnificent production designs of BEMF Stage Director in Residence Gilbert Blin; “the world’s finest continuo team, which you have”; the highly skilled BEMF Baroque Dance Ensemble to bring to life Almira ’s substantial dance sequences; the all-star BEMF Orchestra; and a wide range of superb voices. BEMF will offer five fully-staged performances of Handel’s Almira from June 9 to 16, 2013 at the Cutler Majestic Theatre at Emerson College (219 Tremont Street, Boston, MA, USA), followed by three performances at the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center (14 Castle Street, Great Barrington, MA, USA) on June 21, 22, and 23, 2013 ; all performances will be sung in German with English subtitles. -

Nicholas Mcgegan Principal Guest Conductor

Nicholas McGegan Principal Guest Conductor As he embarks on his fourth decade on the podium, Nicholas McGegan — long hailed as “one of the finest baroque conductors of his generation” (London Independent) and “an expert in 18th- century style” (The New Yorker) — is recognized for his probing and revelatory explorations of music of all periods. In 2015, Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra celebrates his 30th year as music director and he is also Principal Guest Conductor of the Pasadena Symphony. McGegan has established the San Francisco-based Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Philharmonia Chorale as one of the world’s leading period-performance ensembles, with notable appearances at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, the London Proms, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, and the International Handel Festival, Göttingen. PBO’s 2015/16 season sees the orchestra returning to Carnegie Hall for a performance of Scarlatti’s La Gloria di primavera, in addition to tours of the piece in California’s Bay Area and Quebec. As a guest conductor, McGegan’s 15/16 season features appearances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic (with which he has appeared annually for nearly 20 years), St. Louis, Baltimore, BBC Scottish, RTÉ National, and New Zealand Symphonies; the Cleveland Orchestra/Blossom Music Festival; and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s at Caramoor and Carnegie Hall. Throughout his career, McGegan has defined an approach to period style that sets the current standard: intelligent, infused with joy, and never dogmatic. Under his leadership Philharmonia Baroque continues to expand its repertoire into the Romantic Era and beyond. Calling the group’s recent recording of the Brahms Serenades “a truly treasurable disc,” James R. -

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia

Title Artist Label Tchaikovsky: Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 6689 Prokofiev: Two Sonatas for Violin and Piano Wilkomirska and Schein Connoiseur CS 2016 Acadie and Flood by Oliver and Allbritton Monroe Symphony/Worthington United Sound 6290 Everything You Always Wanted to Hear on the Moog Kazdin and Shepard Columbia M 30383 Avant Garde Piano various Candide CE 31015 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 352 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 353 Claude Debussy Melodies Gerard Souzay/Dalton Baldwin EMI C 065 12049 Honegger: Le Roi David (2 records) various Vanguard VSD 2117/18 Beginnings: A Praise Concert by Buryl Red & Ragan Courtney various Triangle TR 107 Ravel: Quartet in F Major/ Debussy: Quartet in G minor Budapest String Quartet Columbia MS 6015 Jazz Guitar Bach Andre Benichou Nonsuch H 71069 Mozart: Four Sonatas for Piano and Violin George Szell/Rafael Druian Columbia MS 7064 MOZART: Symphony #34 / SCHUBERT: Symphony #3 Berlin Philharmonic/Markevitch Dacca DL 9810 Mozart's Greatest Hits various Columbia MS 7507 Mozart: The 2 Cassations Collegium Musicum, Zurich Turnabout TV-S 34373 Mozart: The Four Horn Concertos Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Mason Jones Columbia MS 6785 Footlifters - A Century of American Marches Gunther Schuller Columbia M 33513 William Schuman Symphony No. 3 / Symphony for Strings New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 7442 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Westminster Choir/various artists Columbia ML 5200 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 (Pathetique) Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Columbia ML 4544 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 Cleveland Orchestra/Rodzinski Columbia ML 4052 Haydn: Symphony No 104 / Mendelssohn: Symphony No 4 New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia ML 5349 Porgy and Bess Symphonic Picture / Spirituals Minneapolis Symphony/Dorati Mercury MG 50016 Beethoven: Symphony No 4 and Symphony No. -

HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for Cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009

CORO CORO HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009 “Overall, this disc ranks as The Sixteen’s most exciting achievement in its impressive Handel discography.” HANDEL gramophone Choruses HANDEL: Dixit Dominus cor16076 STEFFANI: Stabat Mater The Sixteen adds to its stunning Handel collection with a new recording of Dixit Dominus set alongside a little-known treasure – Agostino Steffani’s Stabat Mater. THE HANDEL COLLECTION cor16080 Eight of The Sixteen’s celebrated Handel recordings in one stylish boxed set. The Sixteen To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit HARRY CHRISTOPHERS www.thesixteen.com cor16180 He is quite simply the master of chorus and on this compilation there is much rejoicing. Right from the outset, a chorus of Philistines revel in Awake the trumpet’s lofty sound to celebrate Dagon’s festival in Samson; the Israelites triumph in their victory over Goliath with great pageantry in How excellent Thy name from Saul and we can all feel the exuberance of I will sing unto the Lord from Israel in Egypt. There are, of course, two Handel oratorios where the choruses dominate – Messiah and Israel in Egypt – and we have given you a taster of pure majesty in the Amen chorus from Messiah as well as the Photograph: Marco Borggreve Marco Photograph: dramatic ferocity of He smote all the first-born of Egypt from Israel in Egypt. Handel is all about drama; even though he forsook opera for oratorio, his innate sense of the theatrical did not leave him. Just listen to the poignancy of the opening of Act 2 from Acis and Galatea where the chorus pronounce the gloomy prospect of the lovers and the impending appearance of the monster Polyphemus; and the torment which the Israelites create in O God, behold our sore distress when Jephtha commands them to “invoke the holy name of Israel’s God”– it’s surely one of his greatest fugal choruses. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Bach Festival the First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation

Bach Festival The First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 1921, 2013 THE 2013 BACH FESTIVAL IS MADE POSSIBLE BY: e Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil DEDICATION ELINORE LOUISE BARBER 1919-2013 e Eighty-rst Annual Bach Festival is respectfully dedicated to Elinore Barber, Director of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute from 1969-1998 and Editor of the journal BACH—both of which she helped to found. She served from 1969-1984 as Professor of Music History and Literature at what was then called Baldwin-Wallace College and as head of that department from 1980-1984. Before coming to Baldwin Wallace she was from 1944-1969 a Professor of Music at Hastings College, Coordinator of the Hastings College-wide Honors Program, and Curator of the Rinderspacher Rare Score and Instrument Collection located at that institution. Dr. Barber held a Ph.D. degree in Musicology from the University of Michigan. She also completed a Master’s degree at the Eastman School of Music and received a Bachelor’s degree with High Honors in Music and English Literature from Kansas Wesleyan University in 1941. In the fall of 1951 and again during the summer of 1954, she studied Bach’s works as a guest in the home of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Since 1978, her Schweitzer research brought Dr. Barber to the Schweitzer House archives (Gunsbach, France) many times. In 1953 the collection of Dr. Albert Riemenschneider was donated to the University by his wife, Selma. Sixteen years later, Dr. Warren Scharf, then director of the Conservatory, and Dr. -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 | Peter Jay Sharp Theater FRANCE ANDRÉ CAMPRA Ouverture from L’Europe Galante (1660–1744) SOUTHERN EUROPE: ITALY AND SPAIN JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus (1697–1764) Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK Menuet from Don Juan (1714–87) MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies (1657–1726) de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, (1709-70) after Domenico Scarlatti CELTIC LANDS: SCOTLAND AND IRELAND GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 (1681–1767) NATHANIEL GOW Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and (1763–1831) Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 EASTERN EUROPE: POLAND, BOHEMIA, AND HUNGARY ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes RUSSIA TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Program continues 1 EUROPE DREAMS OF THE EAST: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 PERSIA AND CHINA JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes (1683–1764) Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois -

1 Press Release ORCHESTRA of ST. LUKE's ANNOUNCES ITS

Press Release ORCHESTRA OF ST. LUKE’S ANNOUNCES ITS 2020–2021 SERIES PRESENTED BY CARNEGIE HALL AND LED BY PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR BERNARD LABADIE December 2020 Program Begins Multi-Year Exploration of Mendelssohn’s Masterpieces with Violinist Isabelle Faust, Soprano Lauren Snouffer, Mezzo-Soprano Cecelia Hall, Women of the Westminster Symphonic Choir, and Actor David Hyde Pierce Pianist Emanuel Ax Joins OSL in January 2021 for a Concert Celebrating Mozart and Schubert La Chapelle Québec Joins OSL for Festive Music for Royals in March 2021, with Soprano Amanda Forsythe, Tenor Samuel Boden, and Bass-Baritone Matthew Brook New York, NY, January 28, 2020 — Orchestra of St. Luke’s (OSL) announced details of its 2020–21 subscription series presented by Carnegie Hall. Principal Conductor Bernard Labadie, a specialist in music of the Baroque and Classical era, will lead the three programs. Joining OSL will be an array of soloists, some of them making their Carnegie Hall or OSL debuts, as well as such returning favorites as the chamber choir founded by Labadie, La Chapelle de Québec, and internationally celebrated pianist Emanuel Ax. In the Carnegie Hall programs, Maestro Labadie will bring his singular artistic vision and historically informed performance practice to New York audiences with works by Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, Handel and Bach. Maestro Labadie opens the series with two works by Felix Mendelssohn on December 3, 2020. The concert serves as a point of departure for the ensemble to embark on a multi-year exploration of the composer's works. Celebrated violinist Isabelle Faust, praised for her “passion, grit and electricity” by The New York Times, makes her OSL debut with Mendelssohn’s beloved Violin Concerto. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XVIII, Number 1 April 2003 A PILGRIMAGE TO IOWA As I sat in the United Airways terminal of O’Hare International Airport, waiting for the recently bankrupt carrier to locate and then install an electric starter for the no. 2 engine, my mind kept returning to David Lodge’s description of the modern academic conference. In Small World (required airport reading for any twenty-first century academic), Lodge writes: “The modern conference resembles the pilgrimage of medieval Christendom in that it allows the participants to indulge themselves in all the pleasures and diversions of travel while appearing to be austerely bent on self-improvement.” He continues by listing the “penitential exercises” which normally accompany the enterprise, though, oddly enough, he omits airport delays. To be sure, the companionship in the terminal (which included nearly a dozen conferees) was anything but penitential, still, I could not help wondering if the delay was prophecy or merely a glitch. The Maryland Handel Festival was a tough act to follow and I, and perhaps others, were apprehensive about whether Handel in Iowa would live up to the high standards set by its august predecessor. In one way the comparison is inappropriate. By the time I started attending the Maryland conference (in the early ‘90’s), it was a first-rate operation, a Cadillac among festivals. Comparing a one-year event with a two-decade institution is unfair, though I am sure in the minds of many it was inevitable. Fortunately, I feel that the experience in Iowa compared very favorably with what many of us had grown accustomed Frontispiece from William Coxe, Anecdotes fo George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith to in Maryland. -

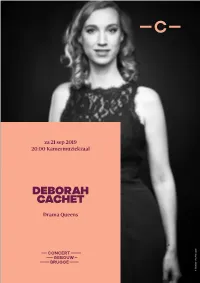

Deborah Cachet

za 21 sep 2019 20.00 Kamermuziekzaal DEBORAH CACHET Drama Queens © Stefaan Achtergael Biografieën Uitvoerders Deborah Cachet (BE) is sinds 2013 bezig Sofie Vanden Eynde (BE) begon op jonge en programma aan een operacarrière met finaleplekken en leeftijd gitaar te spelen, om later over te prijzen in concoursen als die van Froville en schakelen op luit en teorbe. Ze studeerde Innsbruck. Ze maakte deel uit van Le Jardin bij Philippe Malfeyt en Hopkinson Smith des Voix, het jonge-artiestenprogramma en speelde sindsdien bij groepen als Neue van Les Arts Florissants (Arminda in Hofkapelle Graz, Hathor Consort, a nocte Mozarts Finta Giardiniera), en zong de temporis, Vox Luminis, en in duo met Romina rollen van Dido en Didon in Purcells Dido Lischka, Thomas Hobbs, Emma Kirkby, and Aeneas en Desmarests Didon et Énee Lore Binon, Lieselot De Wilde en Rebecca 19.15 Inleiding door Sofie Taes Francesco Cavalli (1602-1676) in een Europese tournee in het kader van de Ockenden. In 2012 creëerde ze Imago Volgi, deh volgi il piede, uit Gli amori Académie Baroque d’Ambronay gedirigeerd Mundi, een ontmoetingsplaats voor oude — d’Apollo e di Dafne (1640) door Paul Agnew. Ze werkt ondertussen en nieuwe, westerse en oosterse muziek, met ensembles als Les Talens Lyriques, en voor verschillende artistieke disciplines. Deborah Cachet: sopraan Stefano Landi (1587-1639) Pygmalion, Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, De productie Divine Madness kon op veel Edouard Catalan: cello T’amai gran tempo, uit Il secondo libro Collegium 1704 (Alphise in Rameaus Les bijval rekenen, in 2018 gevolgd door In My Sofie Vanden Eynde: luit d’arie musicali (1627) Boréades), Correspondances, Le Poème End is My Beginning, een voorstelling rond Bart Naessens: klavecimbel Harmonique, Scherzi Musicali, Les Muffatti, de fascinerende figuur van Mary Stuart Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) L’Achéron en a nocte temporis, met wie ze al gecreëerd op Operadagen Rotterdam.