The Ballad of Balloon Boy” That Can Also Be Found on Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

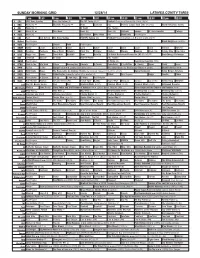

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

M-Ad Shines in Toronto

Volume 44, Issue 3 SUMMER 2013 A BULLETIN FOR EVERY BARBERSHOPPER IN THE MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT M-AD SHINES IN TORONTO ALEXANDRIA MEDALS! DA CAPO maKES THE TOP 10 GImmE FOUR & THE GOOD OLD DAYS EARN TOP 10 COLLEGIATE BROTHERS IN HARMONY, VOICES OF GOTHam amONG TOP 10 IN THE WORLD WESTCHESTER WOWS CROWD WITH MIC-TEST ROUTINE ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, FRANK THE DOG HIT TOP 20 UP ALL NIGHT KEEPS CROWD IN STITCHES CHORUS OF THE CHESAPEAKE, BLACK TIE AFFAIR GIVE STRONG PERFORmaNCES INSIDE: 2-6 OUR INTERNATIONAL COMPETITORS 7 YOU BE THE JUDGE 8-9 HARMONY COLLEGE EAST 10 YOUTH CamP ROCKS! 11 MONEY MATTERS 12-15 LOOKING BACK 16-19 DIVISION NEWS 20 CONTEST & JUDGING YOUTH IN HARMONY 21 TRUE NORTH GUIDING PRINCIPLES 23 CHORUS DIRECTOR DEVELOPMENT 24-26 YOUTH IN HARMONY 27-29 AROUND THE DISTRICT . AND MUCH, MUCH MORE! PHOTO CREDIT: Lorin May ANYTHING GOES! 3RD PLACE BRONZE MEDALIST ALEXANDRIA HARMONIZERS PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS ON STAGE IN TORONTO. INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: QUARTET CONTEST ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, T.J. Carollo, Jeff Glemboski, Larry Bomback and Wayne Grimmer placed 12th. All photos courtesy of Dan Wright. To view more photos, go to www. flickr.com/photosbydanwright UP ALL NIGHT, John Ward, Cecil Brown, Dan Rowland and Joe Hunter placed 28th. DA CAPO, Ryan Griffith, Anthony Colosimo, Wayne FRANK THE Adams and Joe DOG, Tim Sawyer placed Knapp, Steve 10th. Kirsch, Tom Halley and Ross Trube placed 20th. MID’L ANTICS SUMMER 2013 pa g e 2 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: COLLEGIATE QUARTETS THE GOOD OLD DAYS, Fernando Collado, Doug Carnes, Anthony Arpino, Edd Duran placed 10th. -

We Will Rock You”

“We Will Rock You” By Queen and Ben Elton At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 20 By Princess Appau WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS When one walks into the Hippodrome Theatre to view “We Will Rock You,” the common expectation is a compilation of classic rock and roll music held together by a simple plot. This jukebox musical, however, surpasses those expectations by entwining a powerful plot with clever updating of the original 2002 musical by Queen and Ben Elton. The playwright Elton has surrounded Queen’s songs with a plot that highlights the familiar conflict of our era: youths being sycophants to technology. This comic method is not only the key to the show’s success but also the antidote to any fear that the future could become this. The futuristic storyline is connected to many of Queen’s lyrics that foreshadow the youthful infatuation with technology and the monotonous lifestyle that results. This approach is emphasized by the use of a projector displaying programmed visuals of a futuristic setting throughout the show. The opening scene transitions into the Queen song “Radio Gaga,” which further affirms this theme. The scene includes a large projection of hundreds of youth, clones to the cast performing on stage. The human cast and virtual cast are clothed alike in identical white tops and shorts or skirts; they sing and dance in sublime unison, defining the setting of the show and foreshadowing the plot. Unlike most jukebox musicals the plot is not a biographical story of the performers whose music is featured. “We Will Rock You” is set 300 years in the future on the iPlanet when individuality and creativity are shunned and conformity reigns. -

The Image of Streetwalkers in Itzik Manger's and Debora Vogel's

The Image of Streetwalkers in Itzik Manger’s and Debora Vogel’s Ballads by Ekaterina Kuznetsova and Anastasiya Lyubas In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2020) For the online version of this article: http://ingeveb.org/articles/the-image-of-streetwalkers In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2020) THE IMAGE OF STREETWALKERS IN ITZIK MANGER’S AND DEBORA VOGEL’S BALLADS Ekaterina Kuznetsova and Anastasiya Lyubas Abstract: This article focuses on three ballads by Itzik Manger ( Di balade fun der zind, Di balade fun gasn-meydl, Di balade fun der zoyne un dem shlankn husar ) and two ballads by Debora Vogel ( Balade fun a gasn-meydl I un II ). We argue that Manger and Vogel subvert the ballad genre and gender hierarchies by depicting promiscuous female embodiment, theatricality, and the valuation of “lowbrow” culture of shund in their sophisticated poetic practices. These polyphonous texts integrate theatrical and folkloric song elements into “highbrow” Modernist aesthetics. Furthermore, these works by Manger and Vogel draw from both European influences and Jewish cultural traditions; they contend with urban modernity, as well as the resultant changes in the structures of Jewish life. By considering the image of the streetwalker in Manger’s and Vogel’s work, we deepen the understanding of Yiddish creativity as ultimately multimodal and interconnected. 1. Itzik Manger’s and Debora Vogel’s Ballads: Points of Contact Our study aims to bring two Yiddish authors—Itzik Manger and Debora Vogel—into dialogue. Manger and Vogel wrote numerous ballads where they integrated Eastern European folklore and interwar popular Jewish culture into this European literary genre. -

Ballad of the Buried Life

Ballad of the Buried Life From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Ballad of the Buried Life rudolf hagelstange translated by herman salinger with an introduction by charles w. hoffman UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 38 Copyright © 1962 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Hagelstange, Rudolf. Ballad of the Buried Life. Translated by Herman Salinger. Chapel Hill: University of North Car- olina Press, 1962. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469658285_Hagel- stange Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Salinger, Herman. Title: Ballad of the buried life / by Herman Salinger. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 38. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1962] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. Identifiers: lccn unk81010792 | isbn 978-0-8078-8038-8 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5828-5 (ebook) Classification: lcc pd25 .n6 no. -

College Women's 400M Hurdles Championship

College Women's 400m Hurdles Championship EVENT 101THURSDAY 10:00 AM FINAL ON TIME PL ID ATHLETE SCHOOL/AFFILIATION MARK SEC 1 2 Samantha Elliott Johnson C. Smith 57.64 2 2 6 Zalika Dixon Indiana Tech 58.34 2 3 3 Evonne Britton Penn State 58.56 2 4 5 Jessica Gelibert Coastal Carolina 58.84 2 5 19 Faith Dismuke Villanova 59.31 4 6 34 Monica Todd Howard 59.33 6 7 18 Evann Thompson Pittsburgh 59.42 4 8 12 Leah Nugent Virginia Tech 59.61 3 9 11 Iris Campbell Western Michigan 59.80 3 10 4 Rushell Clayton UWI Mona 59.99 2 11 7 Kiah Seymour Penn State 1:00.08 2 12 8 Shana-Gaye Tracey LSU 1:00.09 2 13 14 Deyna Roberson San Diego State 1:00.32 3 14 72 Sade Mariah Greenidge Houston 1:00.37 1 15 26 Shelley Black Penn State 1:00.44 5 16 15 Megan Krumpoch Dartmouth 1:00.49 3 17 10 Danielle Aromashodu Florida Atlantic 1:00.68 3 18 33 Tyler Brockington South Carolina 1:00.75 6 19 21 Ryan Woolley Cornell 1:01.14 4 20 29 Jade Wilson Temple 1:01.15 5 21 25 Dannah Hayward St. Joseph's 1:01.25 5 22 32 Alicia Terry Virginia State 1:01.35 5 23 71 Shiara Robinson Kentucky 1:01.39 1 24 23 Heather Gearity Montclair State 1:01.47 4 25 20 Amber Allen South Carolina 1:01.48 4 26 47 Natalie Ryan Pittsburgh 1:01.53 7 27 30 Brittany Covington Mississippi State 1:01.54 5 28 16 Jaivairia Bacote St. -

Soldiers Claim Success Obama Staff of the New Student Rec- Reation Center Will Be Conduct- Ing Their Fall Fitness Fling from 7 Rallies P.M

SPORTS: Three Titans help US National News: Page 6 Team bring home the gold, page B 10 CSUF Administrator and FEATURES: Check out the Daily Titan’s prof. promoted to V.P. photo essay of the DNC, page 12 Since 1960 Volume 87, Issue 2 Tuesday September 2, 2008 DailyThe Student Voice of California Titan State University, Fullerton DTSHORTHAND Campus Life Soldiers claim success Obama Staff of the new Student Rec- reation Center will be conduct- ing their Fall Fitness Fling from 7 rallies p.m. - 8 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 4. The fling offers visiting -stu dents free personal training on Human Sport Machines. native For more information, stu- dents can call the SRC at 714-278-PLAY. support A New Jersey computer BY JESSIca TERRELL Daily Titan News Editor programmer rigs his [email protected] girlfreind’s video game Obama’s charisma, his ability to to propose marriage inspire, his stance on the environ- ment and his promise for a respon- sible withdrawal from Iraq are a few MORRISTOWN, N.J. (AP) of the most common reasons that – He reprogrammed her favor- young voters cite for supporting the ite video game so a ring and a presidential candidate. marriage proposal would pop up Not Russell Waxman. when his girlfriend reached a cer- One reason that the 25-year-old tain score. Obama delegate from South Dakota And on Saturday, computer said he supports Obama is because programmer Bernie Peng mar- the senator has verbalized misgivings ried Tammy Li in a New Jersey about the Federal government’s rela- ceremony and reception replete The Iraq Veterans Against tions with Native Americans. -

History Early History

Cable News Network, almost always referred to by its initialism CNN, is a U.S. cable newsnetwork founded in 1980 by Ted Turner.[1][2] Upon its launch, CNN was the first network to provide 24-hour television news coverage,[3] and the first all-news television network in the United States.[4]While the news network has numerous affiliates, CNN primarily broadcasts from its headquarters at the CNN Center in Atlanta, the Time Warner Center in New York City, and studios in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. CNN is owned by parent company Time Warner, and the U.S. news network is a division of the Turner Broadcasting System.[5] CNN is sometimes referred to as CNN/U.S. to distinguish the North American channel from its international counterpart, CNN International. As of June 2008, CNN is available in over 93 million U.S. households.[6] Broadcast coverage extends to over 890,000 American hotel rooms,[6] and the U.S broadcast is also shown in Canada. Globally, CNN programming airs through CNN International, which can be seen by viewers in over 212 countries and territories.[7] In terms of regular viewers (Nielsen ratings), CNN rates as the United States' number two cable news network and has the most unique viewers (Nielsen Cume Ratings).[8] History Early history CNN's first broadcast with David Walkerand Lois Hart on June 1, 1980. Main article: History of CNN: 1980-2003 The Cable News Network was launched at 5:00 p.m. EST on Sunday June 1, 1980. After an introduction by Ted Turner, the husband and wife team of David Walker and Lois Hart anchored the first newscast.[9] Since its debut, CNN has expanded its reach to a number of cable and satellite television networks, several web sites, specialized closed-circuit networks (such as CNN Airport Network), and a radio network. -

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China ANNE BIRRELL Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880347 (PDF) 9780824880354 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1988, 1993 Anne Birrell All rights reserved To Hans H. Frankel, pioneer of yüeh-fu studies Acknowledgements I wish to thank The British Academy for their generous Fel- lowship which assisted my research on this book. I would also like to take this opportunity of thanking the University of Michigan for enabling me to commence my degree programme some years ago by awarding me a National Defense Foreign Language Fellowship. I am indebted to my former publisher, Mr. Rayner S. Unwin, now retired, for his helpful advice in pro- ducing the first edition. For this revised edition, I wish to thank sincerely my col- leagues whose useful corrections and comments have been in- corporated into my text. -

Addendum for Outlook & District Music Festival

ADDENDUM FOR OUTLOOK & DISTRICT MUSIC FESTIVAL 2020 PIANO CLASSES JAZZ 713 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 19 years and under (D) 712 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 18 years and under (D) 711 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 17 years and under (D) 710 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 16 years and under (D) 709 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 15 years and under (D) 708 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 14 years and under (D) 707 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 13 years and under (D) 706 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 12 years and under (D) 705 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 11 years and under (D) 704 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 10 years and under (D) 703 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 9 years and under (D) 702 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 8 years and under (D) 701 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 7 years and under (D) 700 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, 6 years and under (D) 720 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 19 years and under (D) 719 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 18 years and under (D) 718 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 16 years and under (D) 717 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 14 years and under (D) 716 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 12 years and under (D) 715 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 10 years and under (D) 714 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, 8 years and under (D) 726 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 18 years and under (D) 725 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 16 years and under (D) 724 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 14 years and under (D) 723 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 12 years and under (D) 722 Piano Duet, Jazz Style, Parent & Son/Daughter, 10 years and under (D) 734 Piano Solo, Jazz Style, Concert Group, 19 years and -

Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture Through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2017 Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens Cristy Dougherty Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dougherty, C. (2017). Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/730/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens By Cristy A. Dougherty A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Communication Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota July 2017 Title: Drag Performance and Femininity: Redefining Drag Culture through Identity Performance of Transgender Women Drag Queens Cristy A. -

Feb March 2013 VE

COLORADO IDAHO KANSASKANSAS MONTANA NEBRASKANEBRASKA Proud members of PROBE www.RMDsing.org Barbershop Harmony Society Classic Collection, 1982 — International Quartet Champions — Storm Front, 2010 2012 Barbershopper of the Year: Dr. Dan Clark, Scottsbluff/Denver Mile High Vol. 35, No. 1 Published by the Rocky Mountain District Association of Chapters Feb/March 2013 NEW MEXICO SOUTH DAKOTA UTAH WYOMING Mountain West Voices 52eighty Die Heart Acafellas Stephen Dugdale, dir. Jay Doughtery, dir. Chelsea Asmus, dir. Brigham Young University Denver Mile High Western Colorado Bernalillo County, NM From the Duke City Sound Congratulations to the fine young men of The 505 for their fine showing at the Midwinter Convention in Orlando. We’re very proud of their singing, earning their highest score to date, second in their Plateau, and third place overall! The 505 Tony Sparks, dir. Bernalillo County, NM RMD VOCAL EXPRESSIONS PAGE 2 FEB/MARCH 2013 Vocal Expressions is published six times yearly Feb/March, April/May, June/July Aug/Sept, Oct/Nov, Dec/Jan issues are posted online Send articles, photos, ads, business cards, news, etc. in ASCII text, jpgs, text only, pdf, or Word documents. Subscription price is $5.00 per year. VE DEADLINES DukeDuke CityCity SoundSound WinsWins WildWild Card!Card! Feb/March: Jan 20 Bernalillo County Chorus invited to Toronto April/May: March 20 June/July: May 20 The Rocky Mountain District chorus prelims in Albuquerque had every- Aug/Sept: July 20 one jazzed after Duke City Sound hit a home run – could the Rocky Oct/Nov: