Roland Jeffery, 'Something in the City', the Georgian Group Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson A Thesis submitted by: Andre Weiss B. A. 1998 Supervisor: Dr. Gavin Stamp Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Architecture Mackintosh School of Architecture, The University of Glasgow September 1999 ProQuest N um ber: 13833922 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13833922 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................9 1. The Previous Claims of an InfluentialRelationship ............................................18 2. An Exploration of the Individual Backgrounds of Thomson and Schinkel .............................................................................................................38 -

University College London: Library DDA Works PPG15 Justification

DRAFT UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON LIBRARY DDA WORKS PPG15 JUSTIFICATION Prepared for UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON ALAN BAXTER & ASSOCIATES MAY 2004 DRAFT CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. Introduction...................................................... 2 2. History of the Wilkins building .......................... 3 3. The Wilkins building today .............................. 10 4. Significance.................................................... 12 5. Impact of proposals ........................................ 15 6. Conclusion ..................................................... 17 Prepared by: William Filmer-Sankey and Lucy Markham Reviewed by: [name] Revised: [date] This report may not be issued to third parties without the prior permission of Alan Baxter & Associates © Alan Baxter & Associates 2004 ALAN BAXTER & ASSOCIATES UCL CONSERVATION STRATEGY REPORT AND PPG 15 JUSTIFICATION • MAY 2004 1 DRAFT 1. INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION This report has been prepared for the Estates and Facilities Division of University College London (UCL). UCL needs to make alterations to the Wilkins building to improve access to the library (on its upper floors) by the end of the year in order to comply with the terms of the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA). In December 2003 Alan Baxter & Associates produced draft Management Guidelines for UCL which identified what is significant about the UCL buildings and to help streamline the process of gaining future listed building consents. This report is based on these Management Guidelines but includes information from the recent opening-up works. The Wilkins Building is Grade I listed. The new access proposals involve removing a staircase, one of which was inserted by TL Donaldson in 1849-51, and installing a lift (along with a new staircase) to provide access for the mobility impaired to the library. This report has been written to accompany an application for listed building consent, and to demonstrate that the alterations are required by the DDA, and are justifiable in terms of the criteria set out in PPG15. -

Download the Annual Report And

SIR JOHN SOANE'S MUSEUM Registered Charity No. 313609 THE ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR 1 APRIL 2013 TO 31 MARCH 2014 HC 359 SIR JOHN SOANE'S MUSEUM Registered Charity No. 313609 THE ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR 1 APRIL 2013 TO 31 MARCH 2014 PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 3(3) OF THE GOVERNMENT RESOURCES AND ACCOUNTS ACT 2000 (AUDIT OF PUBLIC BODIES) ORDER 2003 (SI 2003/1326) ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 15 JULY 2014 HC 359 © Sir John Soane’s Museum (2014) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as Sir John Soane’s Museum copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications Print ISBN 9781474109130 Web ISBN 9781474109147 Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 07071401 07/14 41865 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum TRUSTEES OF SIR JOHN SOANE'S MUSEUM (AS AT 31 MARCH 2014) Guy Elliott (Chairman) Alderman Alison Gowman (Deputy Chairman) Molly Lowell Borthwick Bridget Cherry, OBE, FSA, Hon. -

Masterworks Architecture at the Masterworks: Royal Academy of Arts Neil Bingham

Masterworks Architecture at the Masterworks: Royal Academy of Arts Neil Bingham Royal Academy of Arts 2 Contents President’s Foreword 000 Edward Middleton Barry ra (1869) 000 Sir Howard Robertson ra (1958) 000 Paul Koralek ra (1991) 000 Preface 000 George Edmund Street ra (1871) 000 Sir Basil Spence ra (1960) 000 Sir Colin St John Wilson ra (1991) 000 Acknowledgements 000 R. Norman Shaw ra (1877) 000 Donald McMorran ra (1962) 000 Sir James Stirling ra (1991) 000 John Loughborough Pearson ra (1880) 000 Marshall Sisson ra (1963) 000 Sir Michael Hopkins ra (1992) 000 Architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts 000 Alfred Waterhouse ra (1885) 000 Raymond Erith ra (1964) 000 Sir Richard MacCormac ra (1993) 000 Sir Thomas Graham Jackson Bt ra (1896) 000 William Holford ra, Baron Holford Sir Nicholas Grimshaw pra (1994) 000 The Architect Royal Academicians and George Aitchison ra (1898) 000 of Kemp Town (1968) 000 Michael Manser ra (1994) 000 Their Diploma Works 000 George Frederick Bodley ra (1902) 000 Sir Frederick Gibberd ra (1969) 000 Eva M. Jiricna ra (1997) 000 Sir William Chambers ra (1768, Foundation Sir Aston Webb ra (1903) 000 Sir Hugh Casson pra (1970) 000 Ian Ritchie ra (1998) 000 Member, artist’s presentation) 000 John Belcher ra (1909) 000 E. Maxwell Fry ra (1972) 000 Will Alsop ra (2000) 000 George Dance ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Richard Sheppard ra (1972) 000 Gordon Benson ra (2000) 000 no Diploma Work) 000 Sir Reginald Blomfield ra (1914) 000 H. T. Cadbury-Brown ra (1975) 000 Piers Gough ra (2001) 000 John Gwynn ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Ernest George ra (1917) 000 no Diploma Work) 000 Ernest Newton ra (1919) 000 Ernö Goldfinger ra (1975) 000 Sir Peter Cook ra (2003) 000 Thomas Sandby ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Edwin Lutyens pra (1920) 000 Sir Philip Powell ra (1977) 000 Zaha Hadid ra (2005) 000 bequest from great-grandson) 000 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott ra (1922) 000 Peter Chamberlin ra (1978) 000 Eric Parry ra (2006) 000 William Tyler ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir John J. -

GOSLING Pp01-13.V2:Layout 3

GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 21.07.2009 12:23 Uhr Seite 1 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 2 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 3 CLASSIC DESIGN FOR CONTEMPORARY INTERIORS With contributions by Stephen Calloway, Jean Gomm, Tim Gosling and Jürgen Huber Foreword by Tim Knox, Director, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London Photography by Ray Main PRESTEL MUNICH BERLIN LONDON NEW YORK GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 4 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 5 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 6 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 7 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 8 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 9 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 10 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 21.07.2009 12:23 Uhr Seite 11 Foreword 13 1 The Classical Tradition 14 2 Space, Scale and Light 24 3 Commissioning 42 4 The Art and Craft of Luxury marquetry · mirror and glass · vellum · shagreen · leather lacquer · gilding · eglomise · inlays · accessories 52 5 The Art of Technology 170 6 Contemporary Design in Classic Interiors 192 Keepers of the Flame: Expert Craftsmen 216 Contributors 217 Selected Bibliography 218 Acknowledgements and Photo Credits 220 Index 221 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 12 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 13 Foreword direct link between today’s designers and craftsmen and their Acounterparts in the past is an important one. -

Neoclassical Architecture 1 Neoclassical Architecture

Neoclassical architecture 1 Neoclassical architecture Neoclassical architecture was an architectural style produced by the neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century, both as a reaction against the Rococo style of anti-tectonic naturalistic ornament, and an outgrowth of some classicizing features of Late Baroque. In its purest form it is a style principally derived from the architecture of Classical Greece and the architecture of Italian Andrea Palladio. The Cathedral of Vilnius (1783), by Laurynas Gucevičius Origins Siegfried Giedion, whose first book (1922) had the suggestive title Late Baroque and Romantic Classicism, asserted later[1] "The Louis XVI style formed in shape and structure the end of late baroque tendencies, with classicism serving as its framework." In the sense that neoclassicism in architecture is evocative and picturesque, a recreation of a distant, lost world, it is, as Giedion suggests, framed within the Romantic sensibility. Intellectually Neoclassicism was symptomatic of a desire to return to the perceived "purity" of the arts of Rome, the more vague perception ("ideal") of Ancient Greek arts and, to a lesser extent, sixteenth-century Renaissance Classicism, the source for academic Late Baroque. Many neoclassical architects were influenced by the drawings and projects of Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude Nicolas Ledoux. The many graphite drawings of Boullée and his students depict architecture that emulates the eternality of the universe. There are links between Boullée's ideas and Edmund Burke's conception of the sublime. Pulteney Bridge, Bath, England, by Robert Adam Ledoux addressed the concept of architectural character, maintaining that a building should immediately communicate its function to the viewer. -

Agreg, Anglais Oral

The Royal Academy of Arts Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Academy The Royal Academy of Arts is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly, London, England. The Royal Academy of Arts has a unique position in being an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects whose purpose is to promote the creation, enjoyment and appreciation of the visual arts through exhibitions, education and debate. History The Royal Academy of Arts was founded through a personal act of King George III on 10th December 1768 with a mission to promote the arts of design through education and exhibition. The motive in founding the Academy was twofold: to raise the professional status of the artist by establishing a sound system of training and expert judgment in the arts and to arrange the exhibition of contemporary works of art attaining an appropriate standard of excellence. Behind this concept was the desire to foster a national school of art and to encourage appreciation and interest in the public based on recognised canons of good taste. Fashionable taste in 18th century Britain centered on continental and traditional art forms providing contemporary artists little opportunity to sell their works. From 1746 the Foundling Hospital, through the efforts of William Hogarth, provided an early venue for contemporary artists to show their work in Britain. The success of this venture led to the formation of the Society of Artists and the Free Society of Artists. Both these groups were primarily exhibiting societies and their initial success was marred by internal fractions amongst the artists. -

Architects, Designers, Sculptors and Craftsmen from 1530

ARCHITECTS, DESIGNERS, SCULPTORS AND CRAFTSMEN FROM 1530 R-Z RAMSEY FAMILY (active c.14) Whittington, A. 1980 The Ramsey family of Norwich, Archaeological Journal 137, 285–9 REILLY, Sir Charles H. (1874–1948) Reilly, C.H. 1938 Scaffolding in the Sky: a semi-architectural autobiography Sharples, J., Powers, A., and Shippobottom, M. 1996 Charles Reilly & the Liverpool School of Architecture, 1904–33 RENNIE, John (1761–1821) Boucher, C.T.G. 1963 John Rennie, the life and work of a great engineer RENTON HOWARD WOOD LEVIN PARTNERSHIP Wilcock, R. 1988 Thespians at RHWL, R.I.B.A. Journal 95 (June), 33–9 REPTON, George (1786-1858) Temple, N. 1993 George Repton’s Pavilion Notebook: a catalogue raisonne REPTON, Humphry (1752–1818), see C2 REPTON, John Adey (1775–1860) Warner, T. 1990 Inherited Flair for Rural Harmony, Country Life. 184 (12 April), 92–5. RICHARDSON, Sir A.E. (1880–1964) Houfe, S. 1980 Sir Albert Richardson – the professor Powers, A. 1999 Sir Albert Richardson (RIBA Heinz Gallery exhibition catalogue) Taylor, N. 1975 Sir Albert Richardson: a classic case of Edwardianism, Edwardian Architecture and its Origins, ed. A. Service, 444–59 RICKARDS, Edwin Alfred (1872–1920) Rickards, E.A. 1920 Architects 1 The Art of E.A. Rickards (with a personal sketch by Arnold Bennett) Warren, J. 1975 Edwin Alfred Rickards, Edwardian Architecture and its Origins, ed. A. Service, 338–50 RICKMAN, Thomas (1776–1841) Aldrich, M. 1985 Gothic architecture illustrated: the drawings of Thomas Rickman in New York, Antiq. J. 65 Rickman, T.M. 1901 Notes of the Life of Thomas Rickman Sleman, W. -

Texts and Images of English Modern Architecture (1933- 36)*

Between history, criticism, and wit: texts and images of English modern architecture (1933- 36)* Michela Rosso Introduction In the years between the two wars, Britain occupied a peculiar position in the history of architectural modernism, often remaining on its margins.1 In parallel, until the first three decades of the twentieth century, architectural history in Britain had been a discourse almost exclusively populated by amateurs and historically-minded architects, while its emergence as a discipline of trained and professional scholars only started to occur in the 1930s.2 This essay will examine and compare a small group of articles, books and pamphlets on English modern architecture produced by English architects, journalists, historians and critics, published in the mid-1930s. Their authors (John Betjeman, Peter Fleetwood-Hesketh, John N. Summerson, Clough Williams-Ellis, J. M Richards, P. Morton Shand, Serge Chermayeff, and Osbert Lancaster), were (with the exceptions of Williams-Ellis and Morton Shand) born in the first decade of the twentieth century and are all well- known figures of the interwar London architectural scene whose intellectual and professional itineraries often converged or crossed paths. Whereas not all of them were trained as architects (for instance Betjeman, Morton Shand and Lancaster), most of them shared links of friendship and collaboration, and their backgrounds and careers gravitated around a small number of architecture schools (the Bartlett and the Architectural Association), associations and pressure groups (the MARS and the Georgian Group), and * I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Adrian Forty for generously advising on my work and patiently reading and reviewing it. -

Robert Adam's Revolution in Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hausberg, Miranda Jane Routh, "Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3339. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Abstract ABSTRACT ROBERT ADAM’S REVOLUTION IN ARCHITECTURE Robert Adam (1728-92) was a revolutionary artist and, unusually, he possessed the insight and bravado to self-identify as one publicly. In the first fascicle of his three-volume Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (published in installments between 1773 and 1822), he proclaimed that he had started a “revolution” in the art of architecture. Adam’s “revolution” was expansive: it comprised the introduction of avant-garde, light, and elegant architectural decoration; mastery in the design of picturesque and scenographic interiors; and a revision of Renaissance traditions, including the relegation of architectural orders, the rejection of most Palladian forms, and the embrace of the concept of taste as a foundation of architecture. -

Professor Sir Albert Richardson, P.R.A

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | THURSDAY, 1 AUGUST 2 0 1 3 *UNSEEN & UNTOUCHED FOR ALMOST HALF A CENTURY* CHRISTIE’S CELEBRATES THE DISCERNING TASTE OF PROFESSOR SIR ALBERT RICHARDSON, P.R.A. LONDON, SEPTEMBER 2013 London – Having remained unseen and untouched for almost half a century, Christie’s is pleased to announce that The Collection of Professor Sir Albert Richardson, P.R.A. (1880-1964) - the celebrated collector, architect and President of the Royal Academy (1954-1956) - will be auctioned over two days in London on 18 and 19 September 2013. All great collections are exercises in creativity and self-expression, but rarely do they give such a vivid impression of the collector’s discerning tastes, interests and idiosyncrasies as that formed by Professor Sir Albert Richardson. Providing a window into an older, more generous and civilised world, this collection is complete to its last detail, providing astonishing variety and a stark contrast to the frenetic pace of the modern world. The collection comprises around 650 lots and includes Old Master and British paintings, British watercolours and architectural drawings, English and European furniture, sculpture and objects, garden statuary, books, clocks, musical instruments and Georgian costume. In essence, the sale directly mirrors and celebrates the life and passions of Professor Sir Albert Richardson. The collection is expected to realise in excess of £4 million. Simon Houfe, FSA: “I have lived in my grandfather‟s house for most of my life and for the last forty years have been the guardian of its history, traditions and collections, built up over a period of ninety-five years and more. -

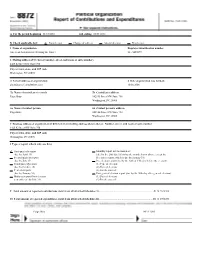

Initial Report Change of A

A For the period beginning 01/01/2010 and ending 03/31/2010 B Check applicable box: ✔ Initial report Change of address Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number American Solutions for Winning the Future 20 - 5457079 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1425 K Street NW Suite 750 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20005 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 10/06/2006 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian©s address Paige Bray 1425 K Street NW Suite 750 Washington, DC 20005 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person©s address Paige Bray 1425 K Street NW Suite 750 Washington, DC 20005 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1425 K Street NW Suite 750 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20005 8 Type of report (check only one box) ✔ First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A)....................................................................................9.