Modelling Phenology and Maturation of the Grapevine Vitis Vinifera L.: Varietal Differences and the Role of Leaf Area to Fruit Weight Ratio Manipulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. from the Beginnings to 1000 Ce

1. From the Beginnings to 1000 ce As the history of French wine was beginning, about twenty-five hundred years ago, both of the key elements were missing: there was no geographi- cal or political entity called France, and no wine was made on the territory that was to become France. As far as we know, the Celtic populations living there did not produce wine from any of the varieties of grapes that grew wild in many parts of their land, although they might well have eaten them fresh. They did cultivate barley, wheat, and other cereals to ferment into beer, which they drank, along with water, as part of their daily diet. They also fermented honey (for mead) and perhaps other produce. In cultural terms it was a far cry from the nineteenth century, when France had assumed a national identity and wine was not only integral to notions of French culture and civilization but held up as one of the impor- tant influences on the character of the French and the success of their nation. Two and a half thousand years before that, the arbiters of culture and civilization were Greece and Rome, and they looked upon beer- drinking peoples, such as the Celts of ancient France, as barbarians. Wine was part of the commercial and civilizing missions of the Greeks and Romans, who introduced it to their new colonies and later planted vine- yards in them. When they and the Etruscans brought wine and viticulture to the Celts of ancient France, they began the history of French wine. -

CHATEAUNEUF DU PAPE Blanc | © Domaine SAINT SIFFREIN | Design

CHATEAUNEUF DU PAPE Blanc Chateauneuf du Pape, certifé Biologique FR01BIO Original blend of the 6 white grapes of the Appellation : Grenache, Clairette, Bourboulenc, Roussanne, PIquepoul and Picardan. Organic certified. THE VINTAGE 2018 LOCATION The Domaine is situated in the area of the CHATEAUNEUF DU PAPE Appellation. TERROIR The terroir is clavey-chalky with large rounded sun-warmed stones, which diffuse a gentle, provenditial heat that helps the grapes to mature. IN THE VINEYARD For 40 years, we cultivate the vineyard with agriculture in an environmental friendly way. The yield is low : 35 hl/ha. The grapes are harvested by hand in the morning at fresh temperature with a selection of the best grapes. VINIFICATION The grapes are directly pressed to extract their juice at low pressure. The juice is then fermented at a controlled temperature to extract the grape aromas. We do add no sulfites during the vinification. 40% is vinified in barriques of 400 liters. AGEING It’s then preserved in fine lees in suspension. Maturing during 10 months. Malo-lactic fermentation is done (it brings more aromatic expression). VARIETALS Grenache blanc 35%, Clairette 30%, Bourboulenc 15%, Roussanne 15%, Picardan 2,50%, Piquepoul 2,50% SERVING To taste now at a temperature 12°C. AGEING POTENTIAL 5 years TASTING NOTES Aromas of white flowers (acacia and lime flower). Surprising richness in the mouth with aromas of vanilla. Great length. FOOD AND WINE PAIRINGS It works particularly well as an aperitif, with selfish or with grilled fish. After 2020, you could taste it with white meats. REVIEWS AND AWARDS Or 1/2 Domaine SAINT SIFFREIN - 3587 Route de CHATEAUNEUF DU PAPE, 84100 ORANGE Tel. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Growing Grapes in Missouri

MS-29 June 2003 GrowingGrowing GrapesGrapes inin MissouriMissouri State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University-Mountain Grove Growing Grapes in Missouri Editors: Patrick Byers, et al. State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University Department of Fruit Science 9740 Red Spring Road Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711-2999 http://mtngrv.missouristate.edu/ The Authors John D. Avery Patrick L. Byers Susanne F. Howard Martin L. Kaps Laszlo G. Kovacs James F. Moore, Jr. Marilyn B. Odneal Wenping Qiu José L. Saenz Suzanne R. Teghtmeyer Howard G. Townsend Daniel E. Waldstein Manuscript Preparation and Layout Pamela A. Mayer The authors thank Sonny McMurtrey and Katie Gill, Missouri grape growers, for their critical reading of the manuscript. Cover photograph cv. Norton by Patrick Byers. The viticulture advisory program at the Missouri State University, Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center offers a wide range of services to Missouri grape growers. For further informa- tion or to arrange a consultation, contact the Viticulture Advisor at the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center, 9740 Red Spring Road, Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711- 2999; telephone 417.547.7508; or email the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center at [email protected]. Information is also available at the website http://www.mvec-usa.org Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction.................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 Considerations in Planning a Vineyard ........................................................ -

Chilean Syrah from a Standing Start, Syrah Has Made It to Number Six in Chile’S Wine Pop Charts in Less Than 20 Years

PANEL TASTING Chilean Syrah From a standing start, Syrah has made it to number six in Chile’s wine pop charts in less than 20 years. And this could be just the beginning, says Peter Richards MW The sTory of syrah in Chile is not a straightforward one. It’s a tale still in the telling, with a murky past, highs and lows, capped by an uncertain future trajectory. This makes it intriguing, especially given that for some time it has been generating a good deal of excitement among wine lovers in the know. The key thing is that there are many – from drinkers to producers and wine critics alike – who hope that this is one saga with a happy ending. The history of syrah in Chile is a matter of debate. records suggest it may have arrived as early as the first half of the 19th century, in the Quinta Normal nursery project in santiago. Its commercial origins in the country, however, are most commonly attributed to Alejandro Dussaillant, a french immigrant who arrived in Chile in 1874 and planted vineyards in the Curicó region which included ‘gross syrah’. (Though this could equally have been the aromatic savoie variety Mondeuse Noire, which goes under this epithet and, according to Wine Grapes, is a close relative of syrah.) either way, by the early 1990s there was scant trace of syrah in Chile, the theory being that, even if it had been there, it was lost in the agrarian reforms of the 1970s. This started to change in the mid-1990s. -

Red Winegrape Varieties for Long Island Vineyards

Strengthening Families & Communities • Protecting & Enhancing the Environment • Fostering Economic Development • Promoting Sustainable Agriculture Red Winegrape Varieties for Long Island Vineyards Alice Wise, Extension Educator, Viticulturist, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County February, 2013; rev. March, 2020 Contemplation of winegrape varieties is a fascinating and challenging process. We offer this list of varieties as potential alternative to the red wine varieties widely planted in the eastern U.S. – Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Pinot Noir. Properly sited and well-managed, these four varieties are capable of producing high quality fruit. Some regions have highlighted one of these varieties, such as Merlot and Cabernet Franc on Long Island and Cabernet Franc in the Finger Lakes. However, many industry members have expressed an interest in diversifying their vineyards. Clearly, there is room for exploration and by doing so, businesses can distinguish themselves from a marketing and stylistic viewpoint. The intent of this article is to introduce a selection of varieties that have potential for Long Island. This is by no means an exhaustive list. These suggestions merit further investigation by the winegrower. This could involve internet/print research, tasting wines from other regions and/or correspondence with fellow winegrowers. Even with a thoughtful approach, it is important to acknowledge that vine performance may vary due to site, soil type and management practices. Fruit quality and quantity will also vary from season to season. That said, a successful variety will be capable of quality fruit production despite seasonal variation in temperature and rainfall. The most prominent features of each variety are discussed based on industry experience, observations and results from the winegrape variety trial at the Long Island Horticultural Research and Extension Center, Riverhead, NY (cited as ‘LIHREC vineyard’). -

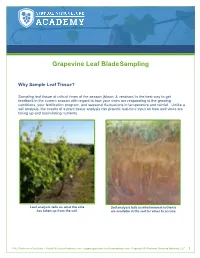

Grapevine Leaf Blade Sampling

Grapevine Leaf Blade Sampling Why Sample Leaf Tissue? Sampling leaf tissue at critical times of the season (bloom & veraison) is the best way to get feedback in the current season with regard to how your vines are responding to the growing conditions, your fertilization program, and seasonal fluctuations in temperature and rainfall. Unlike a soil analysis, the results of a plant tissue analysis can provide real-time input on how well vines are taking up and assimilating nutrients. Leaf analysis tells us what the vine Soil analysis tells us what mineral nutrients has taken up from the soil. are available in the soil for vines to access. Fritz Westover–Viticulturist • VirtualViticultureAcademy.com • [email protected] • Copyright © Westover Vineyard Advising, LLC 1 Leaf Blade Sampling at Bloom Sampling at bloom gives you the chance to optimize vine nutrition to improve cluster growth and berry ripening. Bloom or full bloom 50-75% Beginning of flowering or trace caps fallen Bloom or full bloom bloom 0-30% caps fallen 50-75% caps fallen Flower Cap Fritz Westover–Viticulturist • VirtualViticultureAcademy.com • [email protected] • Copyright © Westover Vineyard Advising, LLC 2 Flower cluster in various stages of bloom and fruit set. Sample time range is from 1 week before to 1 week after bloom. Quick Tip: The optimal time for bloom nutrient sampling is when your earliest variety is at 25-50% bloom. Sample leaves with petioles attached from a location adjacent to flowers. Be consistent – if sampling adjacent to 2nd cluster, repeat for all samples in block. Fritz Westover–Viticulturist • VirtualViticultureAcademy.com • [email protected] • Copyright © Westover Vineyard Advising, LLC 3 Leaf Blade Sampling at Veraison Sampling at veraison allows you to see how effective your fertilization program was for the current season and what nutrients your vines need before bloom of the next season. -

European Commission

29.9.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union C 321/47 OTHER ACTS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to the product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (2020/C 321/09) This notice is published in accordance with Article 17(5) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (1). COMMUNICATION OF A STANDARD AMENDMENT TO THE SINGLE DOCUMENT ‘VAUCLUSE’ PGI-FR-A1209-AM01 Submitted on: 2.7.2020 DESCRIPTION OF AND REASONS FOR THE APPROVED AMENDMENT 1. Description of the wine(s) Additional information on the colour of wines has been inserted in point 3.3 ‘Evaluation of the products' organoleptic characteristics’ in order to add detail to the description of the various products. The details in question have also been added to the Single Document under the heading ‘Description of the wine(s)’. 2. Geographical area Point 4.1 of Chapter I of the specification has been updated with a formal amendment to the description of the geographical area. It now specifies the year of the Geographic Code (the national reference stating municipalities per department) in listing the municipalities included in each additional geographical designation. The relevant Geographic Code is the one published in 2019. The names of some municipalities have been corrected but there has been no change to the composition of the geographical area. This amendment does not affect the Single Document. 3. Vine varieties In Chapter I(5) of the specification, the following 16 varieties have been added to those listed for the production of wines eligible for the ‘Vaucluse’ PGI: ‘Artaban N, Assyrtiko B, Cabernet Blanc B, Cabernet Cortis N, Floreal B, Monarch N, Muscaris B, Nebbiolo N, Pinotage N, Prior N, Soreli B, Souvignier Gris G, Verdejo B, Vidoc N, Voltis B and Xinomavro N.’ (1) OJ L 9, 11.1.2019, p. -

French Wine Scholar

French Wine Scholar Detailed Curriculum The French Wine Scholar™ program presents each French wine region as an integrated whole by explaining the impact of history, the significance of geological events, the importance of topographical markers and the influence of climatic factors on the wine in the the glass. No topic is discussed in isolation in order to give students a working knowledge of the material at hand. FOUNDATION UNIT: In order to launch French Wine Scholar™ candidates into the wine regions of France from a position of strength, Unit One covers French wine law, grape varieties, viticulture and winemaking in-depth. It merits reading, even by advanced students of wine, as so much has changed-- specifically with regard to wine law and new research on grape origins. ALSACE: In Alsace, the diversity of soil types, grape varieties and wine styles makes for a complicated sensory landscape. Do you know the difference between Klevner and Klevener? The relationship between Pinot Gris, Tokay and Furmint? Can you explain the difference between a Vendanges Tardives and a Sélection de Grains Nobles? This class takes Alsace beyond the basics. CHAMPAGNE: The champagne process was an evolutionary one not a revolutionary one. Find out how the method developed from an inexpert and uncontrolled phenomenon to the precise and polished process of today. Learn why Champagne is unique among the world’s sparkling wine producing regions and why it has become the world-class luxury good that it is. BOURGOGNE: In Bourgogne, an ancient and fractured geology delivers wines of distinction and distinctiveness. Learn how soil, topography and climate create enough variability to craft 101 different AOCs within this region’s borders! Discover the history and historic precedent behind such subtle and nuanced fractionalization. -

Increasing Nitrogen Availability at Veraison Through Foliar

HORTSCIENCE 48(5):608–613. 2013. between leaf area and sink, i.e., cluster numbers or size, have resulted in higher rates of Pn (Hunter and Visser, 1988; Palliotti et al., Increasing Nitrogen Availability at 2011; Poni et al., 2008). Although an increase of photosynthesis can compensate for the loss Veraison through Foliar Applications: of source availability during fruit develop- ment and ripening (Candolfi-Vasconcelos and Implications for Leaf Assimilation Koblet, 1991), a compensatory effect can also result from a change in the aging process of the leaves. Older leaves of the canopy, and Fruit Ripening under generally corresponding to leaves in the fruit zone, decrease their Pn after they reach full Source Limitation in ‘Chardonnay’ development (Poni et al., 1994). It has been observed that older leaves can maintain a (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevines higher Pn when a source reduction is imposed (Petrie et al., 2000b). Because cluster demand 1 Letizia Tozzini, Paolo Sabbatini , and G. Stanley Howell for photosynthates varies among different Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University, Plant and Soil stages of development, the response to de- Science Building, East Lansing, MI 48824 foliation can also vary according to pheno- logical stage. For example, an increase in Additional index words. Vitis vinifera, source sink, fruit set, fruit quality and composition, photosynthesis at veraison, independent of yeast available nitrogen (YAN), photosynthesis, foliar fertilizer sink size, was also observed (Petrie et al., 2003). Abstract. Viticulture in Michigan is often limited by cool and humid climate conditions The objective of this study was to deter- that impact vine growth and the achievement of adequate fruit quality at harvest. -

377 Final 2003/0140

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 24.6.2003 COM (2003) 377 final 2003/0140 (ACC) Proposal for a COUNCIL DECISION on the conclusion of an agreement between the European Community and Canada on trade in wines and spirit drinks (presented by the Commission) EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM 1. This agreement between Canada and the European Community is the result of bilateral negotiations which took place from 7 November 2001 to 24 April 2003 on the basis of a negotiating mandate adopted by the Council on 1 August 2001 (Doc. 11170/01). The agreement comprises arrangements for the reciprocal trade in wines and spirit drinks with a view to creating favourable conditions for its harmonious development. 2. The agreement specifies oenological practices which may be used by producers of wine exported to the other Party, as well as a procedure for accepting new oenological practices. The Community's simplified system of certification will be applied to imported wines originating in Canada. Canada will not introduce import certification for Community wines and will simplify the extent of such testing requirements as are currently applied by provinces, within a year of entry into force. Production standards are agreed for wine made from grapes frozen on the vine. Concerning production standards for spirit drinks, the agreement provides that Canada will adhere to Community standards for its exports of whisky to the Community. 3. Procedures whereby geographical indications relating to wines and spirit drinks of either Party may be protected in the territory of the other Party are agreed. The current "generic" status in Canada of 21 wine names will be ended by the following dates: 31 December 2013 for Chablis, Champagne, Port and Porto, and Sherry; 31 December 2008 for Bourgogne and Burgundy, Rhin and Rhine, and Sauterne and Sauternes; the date of entry into force of the agreement for Bordeaux, Chianti, Claret, Madeira, Malaga, Marsala, Medoc and Médoc, and Mosel and Moselle. -

August 2020 Newsletter

AUGUST 2020 Event Report ROSÉ THE DAY AWAY AT PITCH DUNDEE ALSO INSIDE • Rosé Styled Wine: There’s More to it than You Think at First Blush • IWFS Great Weekend in Charleston South Carolina Part 4 Friday 10/18/2019 dinner A publication of the Council Bluffs Branch of the International Wine and Food Society President's Comments Greetings to all; ur July event featuring an Australian food and wine theme was held at Wine, Beer and Spirits. The evening provided an opportunity to sample some unique foods such as emu and kangaroo as well as wonderful wines. ThankO you to Patti and Steve Hipple for a great evening. As summer continues, I find that I am looking for a refreshing summer drink to enjoy on these hot, muggy evenings. A little over a year ago, some of us had the opportunity to be in Portugal on the Douro River cruise. One of the starters each evening was a “White Port” Spritzer. Most are familiar with the red ports but white ports do exist and are reasonably priced. In the Douro, white port is made from Codega, Gouveio, Malvasia Fina, Rabigato and Viosinho grapes. Considered to be the Portuguese equivalent of a gin and tonic, a White Port Spritzer is made with tonic water, orange peel and a sprig of mint added to your favorite white port served over ice. This provides a refreshing and light style summer drink with flavors of apricot, nuts, citrus fruit and peel. “White Port” Spritzer Recipe Mix 2 ounces of white port with 3 ounces of tonic water and add an orange peel.