Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

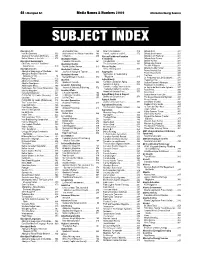

Subject Index

48 / Aboriginal Art Media Names & Numbers 2009 Alternative Energy Sources SUBJECT INDEX Aboriginal Art Anishinabek News . 188 New Internationalist . 318 Ontario Beef . 321 Inuit Art Quarterly . 302 Batchewana First Nation Newsletter. 189 Travail, capital et société . 372 Ontario Beef Farmer. 321 Journal of Canadian Art History. 371 Chiiwetin . 219 African/Caribbean-Canadian Ontario Corn Producer. 321 Native Women in the Arts . 373 Aboriginal Rights Community Ontario Dairy Farmer . 321 Aboriginal Governments Canadian Dimension . 261 Canada Extra . 191 Ontario Farmer . 321 Chieftain: Journal of Traditional Aboriginal Studies The Caribbean Camera . 192 Ontario Hog Farmer . 321 Governance . 370 Native Studies Review . 373 African Studies The Milk Producer . 322 Ontario Poultry Farmer. 322 Aboriginal Issues Aboriginal Tourism Africa: Missing voice. 365 Peace Country Sun . 326 Aboriginal Languages of Manitoba . 184 Journal of Aboriginal Tourism . 303 Aggregates Prairie Hog Country . 330 Aboriginal Peoples Television Aggregates & Roadbuilding Aboriginal Women Pro-Farm . 331 Network (APTN) . 74 Native Women in the Arts . 373 Magazine . 246 Aboriginal Times . 172 Le Producteur de Lait Québecois . 331 Abortion Aging/Elderly Producteur Plus . 331 Alberta Native News. 172 Canadian Journal on Aging . 369 Alberta Sweetgrass. 172 Spartacist Canada . 343 Québec Farmers’ Advocate . 333 Academic Publishing Geriatrics & Aging. 292 Regional Country News . 335 Anishinabek News . 188 Geriatrics Today: Journal of the Batchewana First Nation Newsletter. 189 Journal of Scholarly Publishing . 372 La Revue de Machinerie Agricole . 337 Canadian Geriatrics Society . 371 Rural Roots . 338 Blackfly Magazine. 255 Acadian Affairs Journal of Geriatric Care . 371 Canadian Dimension . 261 L’Acadie Nouvelle. 162 Rural Voice . 338 Aging/Elderly Care & Support CHFG-FM, 101.1 mHz (Chisasibi). -

Red Nominee Bios

RED RED Nominees Red - Life (Lifetime Achievement) This award recognizes an outstanding individual whose work has enriched Vancouver’s LGBTQ community. Individuals must have dedicated at least 10 years of volunteer service to one or more organizations that promotes one or more of the Vancouver Pride Society’s core values. Shawn Ewing I was born in Calgary, Alberta and moved to Vancouver when I was 8. Spent my school years in North Vancouver and graduated from Carson Graham. Since that time, I have lived in various areas of the Lower Mainland as well as a year in Toronto and three years in Calgary. My first involvement with the Vancouver Pride Society (VPS) was in 2001, when I volunteered to be security at the festival site. I saw, first hand, the great need for people to step up and help. That same year I was appointed a Director on the VPS board and also assumed the Parade Director role. At the following Annual General Meeting (AGM), all but two Directors resigned. Randy Atkinson and I remained. After pleading with the few members present at the AGM to join the Board, we were able to continue with the five people that volunteered. The new Treasurer reviewed the finances and discovered the organization was in debt in excess of $100,000. By the time we presented this to the VPS board, we had grown in numbers and had 10 members. Two choices were presented for the VPS board to consider. One, we could just step away. Two, we could dig in and find a way to make it work. -

![Fw: [Wayves-Submissions] Revised Elderberries Newsletter](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3881/fw-wayves-submissions-revised-elderberries-newsletter-2533881.webp)

Fw: [Wayves-Submissions] Revised Elderberries Newsletter

From: "Lynn Murphy" <[email protected]> Subject: [wayves-submissions] Fw: Revised Elderberries Newsletter - January 13, 2013 Date: 2013-01-16 (Wed) 08:29:59 AST To: <[email protected]> 1. Elderberries Potluck Social : Sunday January 27, 2:00 - 4:30 Will you be my (early) Valentine? Potluck social open to LGBT people aged 50+. Free. New participants welcome - you might find that you'd like to join. Please bring an appropriate Valentine food that you would enjoy sharing : something sweet (cookies, chocolate); something red (jellybeans, cranberry juice); something that encourages romantic feelings (oysters on the half shell?). Coffee and tea provided. Please remember, there are no cooking facilities, so finger food is the best option. There is no formal program, but we might have a round-table to share a humourous story from our romantic pasts (no sad break-up tales, please! and keep it moderately non-X-rated). Bring your cards - we could play Hearts! No alcohol, no scents, no pets, no peanuts, please. Support dogs welcome. Location : the Penthouse, 2615 Northwood Terrace, Halifax. Parking on the surrounding streets, or there is a pay-for-park location just across the street from the entrance. 2.Conversations for Connection : a relationship enhancement group for gay male couples. A series of twelve workshops running Saturday January 19 to April 13, 2013, 1:30 pm to 4:30 pm. If you are gay men over 18 years of age, you live together, and you have been a couple for at least two years, you may be eligible for a research study investigating the efficacy of the Hold Me Tight relationship enhancement groups, based on the book Hold Me Tight : Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love, by Dr Sue Johnson. -

PREVENTION REVIVED: Evaluating the Assumptions Campaign © 2005 AIDS Vancouver

PREVENTION REVIVED: Evaluating the Assumptions Campaign © 2005 AIDS Vancouver Authors of this Report: Terry Trussler and Rick Marchand Community Based Research Centre Report Design: Burkhardt Members of the National Advisory Team 2004 Campaign: Robert Allan, AIDS Coalition of Nova Scotia, Halifax Robert Rousseau, Action Séro-Zéro, Montréal Ken Monteith, AIDS Community Care Montreal (ACCM), Montréal Shaleena Theophilus & Darren Fisher, Canadian AIDS Society John Maxwell, AIDS Committee of Toronto Art Zoccole, 2 Spirited People of the 1st Nations, Toronto Mike Payne & Jeremy Johnson, Nine Circles Community Health Centre, Winnipeg Robert Smith, HIV Edmonton, Edmonton Evan Mo, Asian Society for the Intervention of AIDS (ASIA) Olivier Ferlatte, AIDS Vancouver Project Manager: Phillip Banks, AIDS Vancouver Campaign Development: Raul Cabra, Cabra Diseno Andy Williams SF AIDS Foundation Cohort Evaluation Study: Tom Lampinen, Vanguard Cohort Study, BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS Liviana Calzavara & Wendy Medved, Polaris Cohort Study, University of Toronto Think-again.ca Webmaster: Rachel Thompson, AIDS Vancouver Translation: Murielle McCabe Translations; Nestor Systems Program Consultant: Patti Murphy, HIV/AIDS Division, Public Health Agency of Canada Thank you to all the businesses, community agencies, individuals in communities across the country that supported the HIV prevention campaign for gay men. Thank you to all the gay men who participated in the national evaluation survey. Your responses have helped us shape the next campaign. Production -

Politiques Et Ressources LGBTQ Du NB

O Diversité sexuelle et de genre Ressource pédagogique inclusive, Nouveau-Brunswick POLITIQUES ET RESSOURCES LGBTQ DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK POLITIQUES ET RESSOURCES LGBTQ DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK Le répertoire Web des ressources régionales et nationales est continuellement mis à jour. Allez à MonAGH.ca. Politiques du Nouveau-Brunswick Politique 703 7 Politique 322 13 Énoncé de principe sur le harcèlement (AEFNB) 35 Énoncé de principe sur l’homophobie (AEFNB) 37 Énoncé de principe sur l’intimidation (AEFNB) 38 LGBTQ Nouveau-Brunswick Échelle provinciale 39 SIDA Nouveau Brunswick/AIDS New Brunswick, Fredericton Ligne d’écoute Chimo Jeuness, J’ecoute Wabanaki Two-Spirit Alliance (Atlantique) Bathurst 41 Gais.es Nor Gays Inc.. Dieppe 42 TG Moncton Fredericton 42 SIDA Nouveau-Brunswick/AIDS New Brunswick, Fredericton Fredericton Pride Centre pour les victimes d’agression sexuelle de Fredericton Free 2 Be Me Spectrum (UNB) The UNB Safe Spaces Project UNB Sexuality Centre (centre de la sexualité) Moncton 46 Ressources bispirituelles au Canada et aux États-Unis PFLAG Canada – section de Moncton Rivière de la Fierté – River of Pride Inc. Canada 56 SIDA Moncton Inc. Wabanaki Two-Spirit Alliance (Atlantique) SIDA Moncton – Projet Sain et Sauf Native Youth Sexual Health Network Moncton Transgender Support Group (groupe de soutien The North American Aboriginal Two Spirit Information Pages transgenre de Moncton) Two Spirit Circle of Edmonton Society UBU Moncton 2-Spirited People of the 1st Nations Association Un sur dix Two Spirited People of Manitoba Inc. -

January-February 2007 Wayves Punoqun Where You Can Find Wayves New Brunswick

��������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������� ������������������������������������ ���������������������������������� ��������������������������������� ����������������� ����������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������ ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������ ������������������������ �������������� ������������ �������������� �������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 2 January-February 2007 Wayves punoqun Where You Can Find wayves New Brunswick... Bathurst: Gais.es Nor Gays 2007 Call For Durham Bridge: Rivers Edge Campground Fredericton: AIDS New Brunswick; Boldon’s Bookmart; Campus “Smoke” Shoppe, UNB; Molly’s Coffee House / Cargo Bay; Student Submissions Resource Centre, St. Thomas University; UNB/STU Spectrum; West- minster Books, King Street; X- Citement Video, Queen Street It’s been on hiatus for -

William Way LGBT Community Center Periodicals Collection, 1940-Present : Ms.Coll.37

William Way LGBT Community Center periodicals collection, 1940-Present : Ms.Coll.37 Finding aid prepared by John F. Anderies, based on Periodical Holdings index created by Bob Skiba, and appended by George C. Dube. on 2015 PDF produced on July 17, 2019 John J. Wilcox, Jr. LGBT Archives, William Way LGBT Community Center 1315 Spruce Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 [email protected] William Way LGBT Community Center periodicals collection, 1940-Present : Ms.Coll.37 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 4 # ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 A .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Guidelines for Supporting Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Students

Guidelines for Supporting Transgender and Gender-nonconforming Students Guidelines for Supporting Transgender and Gender-nonconforming Students Website References Website references contained within this document are provided solely as a convenience and do not constitute an endorsement by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development of the content, policies, or products of the referenced website. The department does not control the referenced websites and is not responsible for the accuracy, legality, or content of the referenced websites or for that of subsequent links. Referenced website content may change without notice. School boards and educators are required under the department’s Public School Programs’ Network Access and Use Policy to preview and evaluate sites before recommending them for student use. If an outdated or inappropriate site is found, please report it to [email protected]. Guidelines for Supporting Transgender and Gender-nonconforming Students © Crown copyright, Province of Nova Scotia, 2014 Prepared by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development The contents of this publication may be reproduced in part provided the intended use is for non-commercial purposes and full acknowledgment is given to the Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Cover photographs may not be extracted or re-used. Please note that all attempts have been made to identify and acknowledge information from external sources. In the event that a source was overlooked, please contact the Student Services Division, Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, [email protected]. Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Main entry under title. Guidelines for Supporting Transgender and Gender-nonconforming Students / Nova Scotia. -

Family Affairs Newsletter 2010-04-15

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons FAN: Family Affairs Newsletter Newspapers 4-15-2010 Family Affairs Newsletter 2010-04-15 Zack Paakkonen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/fan Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Paakkonen, Zack, "Family Affairs Newsletter 2010-04-15" (2010). FAN: Family Affairs Newsletter. 8. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/fan/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FAN: Family Affairs Newsletter by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 15 APRIL 2010 EWSLETTER EWS, OTES & REMIDERS : ews #1: Poll : I have been asked to pass along various fundraising solicitations from political GLBTQIA organizations as part of the FAN (in other words, e-mails asking for donations to political causes). To that end, I am asking all of you what your opinion is on having these requests as part of the newsletter. I am accepting e-mail votes on the proposal to include fundraising requests or announcements requesting donations in further issues of the FAN. Please e-mail your votes to me at [email protected] . Please put “FAN” or “The FAN” or “family affairs newsletter” in the subject line, as well as a vote somewhere in your e-mail, either “YES” to allow fundraising solicitations or “NO” to not allow such solicitations. Majority vote wins. Votes are due by May 13, 2010, and any changes that are passed would apply to the May 15, 2010 issue. -

Nsrap Media Survey 2010

NSRAP MEDIA SURVEY 2010 A Sampling of News Reports by and About Nova Scotia’s LGBTQ Community Decision on park gate deferred AIDS group questions motive behind Truro proposal to move barrier By MICHAEL TUTTON The Canadian Press Tue. Jan 5 - 4:46 AM TRURO — Truro town councillors put off a vote Monday on whether to restrict access to a park entrance the mayor has labelled a gay pickup area as an advocacy group warned the town could develop a reputation for intolerance. The issue over the gate’s placement sparked controversy last month when Mayor Bill Mills said it was being moved to reduce sexual activity by gay men. "It’s a favourite pickup spot for guys from all over the Maritime provinces," Mills said at the time. “They go up and have a Al McNutt and Karen Kittilsen of the Northern rendezvous and then they go into the woods and do their thing. AIDS Connection Society leave a public hearing in Truro on Monday. (Photo by It’s been known for years and years and is becoming more and ANDREW VAUGHAN / CP) more of a problem." During Monday’s meeting, several councillors reiterated their opposition to the mayor’s comments and said they want to proceed debating whether moving the gate makes sense for other reasons. Charles Cox said he felt he was caught in a personal dilemma because he felt the current layout of the gate creates safety risks to skiers and bikers from cars driving into the small parking area. "I’ve almost personally been backed into," he said. -

Coming out in Primary Healthcare: an Empirical Investigation of a Model of Predictors and Health Outcomes of Lesbian Disclosure

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2013 Coming Out in Primary Healthcare: An Empirical Investigation of a Model of Predictors and Health Outcomes of Lesbian Disclosure Melissa St. Pierre University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation St. Pierre, Melissa, "Coming Out in Primary Healthcare: An Empirical Investigation of a Model of Predictors and Health Outcomes of Lesbian Disclosure" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 4880. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/4880 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. Coming Out in Primary Healthcare: An Empirical Investigation of a Model of Predictors and Health Outcomes of Lesbian Disclosure by Melissa St. Pierre A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Psychology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada © 2013 Melissa St. -

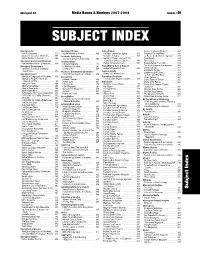

Subject Index

Aboriginal Art Media Names & Numbers 2007-2008 Alumni / 49 SUBJECT INDEX Aboriginal Art Aboriginal Women Aging/Elderly Québec Farmers’ Advocate . 343 Inuit Art Quarterly . 313 Native Women in the Arts . 383 Canadian Journal on Aging . 379 Regional Country News . 345 Journal of Canadian Art History. 381 Academic Publishing Geriatrics & Aging. 303 La Revue de Machinerie Agricole . 347 Native Women in the Arts . 383 Journal of Scholarly Publishing . 382 Geriatrics Today: Journal of the Rural Roots . 348 Aboriginal Government Relations Acadian Affairs Canadian Geriatrics Society . 381 Rural Voice . 348 Parliamentary Names & Numbers. 396 L’Acadie Nouvelle. 174 Journal of Geriatric Care . 381 Saskatchewan Farm Life . 349 Aboriginal Governments Le Moniteur Acadien. 242 Aging/Elderly Care & Support The Saskatchewan Stockgrower. 349 Chieftain: Journal of Traditional Le Ven’D’est . 365 Journal of Geriatric Care . 381 Sheep Canada . 351 Simmental Country. 352 Governance . 379 Access to Government Information Aging & Health Journal of Geriatric Care . 381 Southern Farm Guide. 353 Aboriginal Issues Parliamentary Names & Numbers. 396 La Terre de Chez-Nous . 357 Aboriginal Languages of Manitoba . 196 Accounting Agricultural Practices Union Farmer . 364 Aboriginal Peoples Television Beyond Numbers . 265 The Canadian Organic Grower . 277 Valley Farmers’ Forum. 365 Network (APTN) . 85 Bottom Line . 267 Agriculture Voice of the Farmer . 367 Aboriginal Times . 184 CAmagazine . 270 Aberdeen Angus World . 255 Voice of the Farmer (Central Alberta Native News. 184 CGA Magazine . 281 Agri Digest. 257 Editions) . 367 Alberta Sweetgrass. 184 Management Magazine . 320 The Agri Times . 257 Western Dairy Farmer . 369 Anishinabek News . 200 Outlook . 334 Agricom . 257 Western Hog Journal . 370 Batchewana First Nation Newsletter.