PREVENTION REVIVED: Evaluating the Assumptions Campaign © 2005 AIDS Vancouver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN104: HRM Asset Names, October 17, 2017 – April 15, 2018

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 14.1.4 Halifax Regional Council November 27, 2018 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: October 9, 2018 SUBJECT: AN104: HRM Asset Names, October 17, 2017 – April 15, 2018 ORIGIN HRM has received asset naming requests from the period October 17, 2017 to April 15, 2018. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Administrative Order Number 46, Respecting HRM Asset Naming Policies RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council: 1. approve: (a) The addition of the name Mel Boutilier to the existing Commemorative Names List as shown on Attachment A; (b) The renaming of Arnold D Johnson Playfield to Arnold D Johnson Sport Field and Silver Hill Park to Silvers Hill Park to correct administrative errors as shown on Attachment B; (c) The renaming of Inglis Street Park to Raymond Taavel Park, Halifax, Keltic Garden Playground to Keltic Gardens Park, Lawrencetown, and Two River Park to Partridge Nest Drive Park, Mineville, as shown on Attachment C, D, and E; (d) The renaming of Flagstone Ballfield 1 to Dan C MacDonald Memorial Ballfield, Cole Harbour, as shown on Attachment F; and (e) The administrative park names as shown on Attachment G. AN104: HRM Asset Names, October 17, 2017to April 15, 2018 Council Report - 2 - November 27, 2018 BACKGROUND HRM’s Asset Naming Policy Administrative Order (A.O.46) allows any person or group to apply for a commemorative name for HRM assets, particularly streets, parks or buildings. The A.O. requires the Civic Addressing Coordinator to consult with at least one representative from each asset category, the municipal archivist, and a representative from HRM Cultural Affairs on each application. -

Police, Journalists and Crimes of HIV Non-Disclosure

REVUE DE DROIT D’OTTAWA OTTAWA LAW REVIEW 2014-2015 Volume 46, no 1 Volume 46, No 1 Faculté de droit, Section de common law Faculty of Law, Common Law Section 127 Releasing Stigma: Police, Journalists and Crimes of HIV Non-Disclosure KYLE KIRKUP 127 Releasing Stigma: Police, Journalists and Crimes of HIV Non-Disclosure KYLE KIRKUP* In 2010, a 29-year-old gay man in Ottawa who had En 2010, un homosexuel de 29 ans, résidant à Ottawa, recently learned he was HIV-positive was arrested qui venait d’apprendre qu’il était séropositif, a été arrêté and charged with several criminal offences, including et accusé d’un certain nombre d’infractions criminelles, aggravated sexual assault and later attempted murder. notamment d’agression sexuelle grave et, par la suite, de Two days after his arrest, the Ottawa Police Service tentative de meurtre. Deux jours après son arrestation, released his photo to the public, along with his name, le Service de police d’Ottawa publiait sa photo, ainsi que details of the sexual encounters and his personal son nom, les détails de ses relations sexuelles et des ren- health information. Using this series of events as a seignements personnels concernant sa santé. En se ser- case study, this paper examines the complex ques- vant de cette série d’événements à titre d’étude de cas, tions raised when police services issue press releases l’auteur de ce texte examine les questions complexes in alleged HIV non-disclosure cases, and journalists soulevées par le fait que les services de police diffusent subsequently convey these stories to the public. -

Nancy Nicol Page 1 of 32 Program: Visual Arts July 1

Nancy Nicol Page 1 of 32 Program: Visual Arts July 1, 2009 CURRICULUM VITAE 1) Nancy Nicol Associate Professor Department of Visual Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts Goldfarb Centre for Fine Arts, room 237 [email protected] 2. DEGREES 1977 Master of Fine Arts, York University 1974 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Sir George Williams (Concordia University) 3. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 1995 – Associate Professor, Visual Arts Dept., FFA, York University 2000 - 03 Graduate Programme Director, MFA Programme in Visual Arts 1989 - 95 Assistant Professor, Visual Arts Dept., FFA, York University 1989 Appointment to Graduate Faculty, MFA program 1988 - 89 Instructor, Castle Frank High-School and South Central School of Commerce, Continuing Education, Toronto Board of Education 1983 - 88 Instructor, Inner City Angels (Art programs in public schools) Instructor, `Artists in the Schools Program', The Ontario Arts Council 1983 Course director, video art, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, (summer) 1982 - 83 Course director: Interdisciplinary studio, Visual Arts Dept., FFA, York University 1980 - 81 Course director: printmaking, Visual Arts Dept., Fanshaw College, London 1979 - 80 Course director: drawing, Mohawk College, Hamilton 1976 - 77 Teaching Assistant: intro studio, Dept. of Visual Arts, FFA, York University 4. HONOURS (Awards/Prizes) 2009 Short-listed for the Derek Oyston CHE Film Prize, for One Summer in New Paltz, a Cautionary Tale, 23rd London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, British Film Institute, London, UK. 2007 Honourable Mention for Best Canadian Female Director -

From Paper, to Microform, to Digital? Serials at the Arquives: Canada's LGBTQ2+ Archives Donald W. Mcleod

From Paper, to Microform, to Digital? Serials at the ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives Donald W. McLeod Abstract The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives, founded in 1973, holds one of the largest collections of queer serials in the world, with more than ten thousand titles. Most are on paper, but formats have been evolving. Beginning in the 1980s, the ArQuives participated in small-scale microfilming projects. Microfilming of the collection increased greatly in 2005, when Primary Source Microfilm (PSM) undertook a large project to film a portion of the collection, resulting in 211 reels devoted to international gay and lesbian periodicals and newsletters. The PSM project was later repurposed and expanded by Gale Cengage, beginning in 2015, and forms part of its Archives of Sexuality and Gender online product. This paper examines the evolution of the ArQuives’ serial holdings from paper to microform to digital formats, and explores recent in-house digitization efforts and future prospects for expanding access to these materials. Résumé Les ArQuives : les archives LGBTQ2+ canadiennes, fondées en 1973, détiennent une des plus importantes collections de périodiques queer au monde, comprenant plus de dix mille titres. La majorité sont sur papier, mais les formats sont en évolution. Depuis les années 1980, les ArQuives participent à des projets de microfilmage de petite envergure. Le microfilmage a vu une augmentation importante en 2005, lorsque Primary Source Microfilm (PSM) a entrepris un grand projet consistant à microfilmer une portion de la collection, ayant pour résultat 211 bobines consacrées aux bulletins et périodiques gais et lesbiens internationaux. Par la suite, à partir de 2015, le projet PSM a été transformé et élargi par Gale Cengage, et fait maintenant partie de son produit en ligne Archives of Sexuality and Gender. -

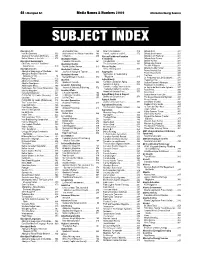

Subject Index

48 / Aboriginal Art Media Names & Numbers 2009 Alternative Energy Sources SUBJECT INDEX Aboriginal Art Anishinabek News . 188 New Internationalist . 318 Ontario Beef . 321 Inuit Art Quarterly . 302 Batchewana First Nation Newsletter. 189 Travail, capital et société . 372 Ontario Beef Farmer. 321 Journal of Canadian Art History. 371 Chiiwetin . 219 African/Caribbean-Canadian Ontario Corn Producer. 321 Native Women in the Arts . 373 Aboriginal Rights Community Ontario Dairy Farmer . 321 Aboriginal Governments Canadian Dimension . 261 Canada Extra . 191 Ontario Farmer . 321 Chieftain: Journal of Traditional Aboriginal Studies The Caribbean Camera . 192 Ontario Hog Farmer . 321 Governance . 370 Native Studies Review . 373 African Studies The Milk Producer . 322 Ontario Poultry Farmer. 322 Aboriginal Issues Aboriginal Tourism Africa: Missing voice. 365 Peace Country Sun . 326 Aboriginal Languages of Manitoba . 184 Journal of Aboriginal Tourism . 303 Aggregates Prairie Hog Country . 330 Aboriginal Peoples Television Aggregates & Roadbuilding Aboriginal Women Pro-Farm . 331 Network (APTN) . 74 Native Women in the Arts . 373 Magazine . 246 Aboriginal Times . 172 Le Producteur de Lait Québecois . 331 Abortion Aging/Elderly Producteur Plus . 331 Alberta Native News. 172 Canadian Journal on Aging . 369 Alberta Sweetgrass. 172 Spartacist Canada . 343 Québec Farmers’ Advocate . 333 Academic Publishing Geriatrics & Aging. 292 Regional Country News . 335 Anishinabek News . 188 Geriatrics Today: Journal of the Batchewana First Nation Newsletter. 189 Journal of Scholarly Publishing . 372 La Revue de Machinerie Agricole . 337 Canadian Geriatrics Society . 371 Rural Roots . 338 Blackfly Magazine. 255 Acadian Affairs Journal of Geriatric Care . 371 Canadian Dimension . 261 L’Acadie Nouvelle. 162 Rural Voice . 338 Aging/Elderly Care & Support CHFG-FM, 101.1 mHz (Chisasibi). -

Januar Februar März Neujahr 01 Mo 01 Do 01 Do Wahl Des Bmrl 2017, München Amsterdam Bear Pride 2018 02 Di 02 Fr Röschen Sitzung, Köln 2

BOX Magazin EVENTKALENDER 2018 januar februar märz Neujahr 01 Mo 01 Do 01 Do Wahl des BMrL 2017, München Amsterdam Bear Pride 2018 02 Di 02 Fr Röschen Sitzung, Köln 2. + 3.2. 02 Fr Amsterdam/NL 1. - 5.3. www.birkenapotheke.de Mr. Rubber Italy 2018, Rom/I 03 Mi 03 Sa KG Regenbogen Sitzungsparty, D`dorf 03 Sa 9. Festliche Operngala, Düsseldorf Maspalomas Carnaval 2018 04 Do 04 So 04 So Gran Canaria/ES 2. - 11.3. Gay Ski-Week 2018 05 Fr 05 Mo 05 Mo Lenzerheide/CH 3. - 10.3. Rainbow Reykjavik Winter Pride 06 Sa 06 Di Reykjavik/IS 8. - 11.2. 06 Di www.westgate-apotheke.de 07 So 07 Mi KG Regenbogen Hupenball, D`dorf 07 Mi ITB 2018, Berlin 7. - 11.3. Weiberfastnacht LMC Vienna Skin Weekend 2018 08 Mo 08 Do Wien/A 9. - 11.2. 08 Do International Bear Convergence 09 Di 09 Fr Palm Springs/USA 8. - 12.2. 09 Fr Röschen Sitzung, Köln 9. + 10.2. 10 Mi 10 Sa KG Regenbogen Tunte Lauf, D`dorf 10 Sa 11 Do 11 So 11 So Mid-Atlantic Leather Weekend 2018 Rosenmontag Maspalomas Bear Carnival 2018 12 Fr Washington DC/USA 12. - 14.1. 12 Mo 12 Mo Gran Canaria/ES 12. - 19.3. Fastnacht 13 Sa DJ Night im Gentle Bears. Köln 13 Di Mardi Gras, New Orleans/USA 13 Di Aschermittwoch 14 So Gay Ski Week Aspen/USA 14.- 21.1. 14 Mi 14 Mi North American BearWeekend Mr. Leather & Bear Deaf Germany 15 Mo 15 Do Lexington/USA 15. -

Gaycalgary and Edmonton Magazine, June 2007

June 2007 Issue 44 FREE of charge PPrideride 20072007 GuideGuide Inside!Inside! PProudroud SSponsorsponsors oof:f: >> STARTING ON PAGE 16 GLBT RESOURCE • CALGARY & EDMONTON 2 gaycalgary and edmonton magazine #44, June 2007 gaycalgary and edmonton magazine #44, June 2007 3 4 gaycalgary and edmonton magazine #44, June 2007 Established originally in January 1992 as Men For Men BBS by MFM Communications. Named changed to 10 GayCalgary.com in 1998. Stand alone company as of January 2004. First Issue of GayCalgary.com Magazine, November 2003. Name adjusted in November 2006 to GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine. Publisher Steve Polyak & Rob Diaz-Marino, [email protected] Table of Contents Editor Rob Diaz Marino, editor@gaycalgary. com 7 That Personal Touch 35 Original Graphic Design Deviant Designs Letter from the Publisher Advertising Steve Polyak [email protected] 10 Priape Swimwear 2007 Contributors Winners of the Priape Model Search Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz-Marino, Jason Clevett, Jerome Voltero, Kevin Alderson, Benjamin 14 Gay Pride Event Listing - Hawkcliffe, Stephen Lock, Arthur McComish, 16 Allison Brodowski , and the Gay and Lesbian Calgary Community of Calgary Photographer 15 Gay Pride Event Listing - Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz-Marino Edmonton Videographer Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz-Marino 16 Map & Event Listings Please forward all inquiries to: Find out what’s happening GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine Suite 100, 215 14th Avenue S.W. 23 Gay Legalese Calgary, Alberta T2R 0M2 Phone (403) 543-6960 or toll free (888) 24 Bitter Girl -

Pride Month, Pride Season, Pride Forever (Pdf)

URBAN UNIT RURAL AND SUBURBAN UNIT PRIVATE SECTOR UNITS June 11, 2020 Pride month, pride season, pride forever built on a consciousness of interconnected equity struggles. So this year, we and allies are paying better attention to intersectionality and the origins of Pride – which began with the activism of black trans women including Marsha P. Johnson. We encourage members to learn more about the history of the LGBTQ equity struggle – it's far deeper and more complex than what you see in the mainstream coverage of Pride events. Meanwhile, the COVID-19 crisis aggravates and amplifies long- existing inequalities in our social systems. Pride events are a beautiful and Like other equity-seeking groups, complex union of celebration and the LGBTQ community has been hit resistance. Over the decades, Pride disproportionately in many ways by festivals and parades have done so the crisis, with its impact on much for visibility, community finances, employment access, organizing, and bringing LGBTQ housing, medical care, and other issues and achievements into the issues that are more dangerous for spotlight. anyone who was already facing oppression and discrimination. This year is a very unique moment in the same struggle. We're currently Be Safe and Healthy inspired by Pride Hamilton's recent statement, “Pride Started as a Riot” This year, public protest and – you can see it at festivities look different. Facing the https://www.pridehamilton.com/ challenges of the COVID-19 crisis, Pride organizations are figuring out Our communities and allies are how to demonstrate and rising up against racism, and coping celebrate with safety in mind, with with the COVID-19 pandemic. -

2013-Queer-Ontario-Resource-List

Queer Ontario Resource List (Updated May 2013) Table of Contents Non-Fiction Books………………………………………………………………...2 – 39 Chapters in Books……………………………………………………………..….40 – 44 Journal Articles…………………………………………………………………...45 – 58 Journals – Special Issues…………………………………………………………58 – 61 Conference Papers………………………………………………………………..61 – 63 Biographies and Memoires……………………………………………………….63 – 69 Web-Based Publications and News………………………………………………70 – 81 Films and Documentaries………………………………………………….……...81 – 90 Like-Minded Individuals, Blogs and Organizations……………………………...90 – 91 Who We Are Queer Ontario is a provincial network of gender and sexually diverse individuals — and their allies — who are committed to questioning, challenging, and reforming the laws, institutional practices, and social norms that regulate queer people. Operating under liberationist and sex-positive principles, we fight for accessibility, recognition, and pluralism, using social media and other tactics to engage in political action, public education, and coalition-building. www.queerontario.org Page 1 of 91 Queer Ontario Resource List (Updated May 2013) Non-Fiction Books 1. Adam, B.D. (1987). The rise of a gay and lesbian movement . Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers. Although the Stonewall riots in New York City in June 1969 are generally considered the beginning of the Gay Liberation movement, "the first social movement to advance the civil rights of gay people was found in Germany in 1897." Amplifying John Lauritsen and David Thorstad's excellent Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935) (1974), sociologist Adam reviews the social, historic, and economic conditions surrounding the development of gay rights worldwide. Using secondary sources, he interweaves individuals, episodes, and examples into an overall picture, chronicling the fits and starts of lesbian and gay rights movements to the present. An extensive list of references supplements the annotated selected bibliography of this comprehensive international history. -

Federal Court Final Settlement Agreement 1

1 Court File No.: T-370-17 FEDERAL COURT Proposed Class Proceeding TODD EDWARD ROSS, MARTINE ROY and ALIDA SATALIC Plaintiffs - and - HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Defendant FINAL SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT WHEREAS: A. Canada took action against members of the Canadian Armed Forces (the "CAF"), members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (the "RCMP") and employees of the Federal Public Service (the “FPS”) as defined in this Final Settlement Agreement (“FSA”), pursuant to various written policies commencing in or around 1956 in the military and in or around 1955 in the public service, which actions included identifying, investigating, sanctioning, and in some cases, discharging lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender members of the CAF or the RCMP from the military or police service, or terminating the employment of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender employees of the FPS, on the grounds that they were unsuitable for service or employment because of their sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression (the “LGBT Purge”); B. In 2016, class proceedings were commenced against Canada in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, the Quebec Superior Court and the Federal Court of Canada in connection with the LGBT Purge, and those proceedings have been stayed on consent or held in abeyance while this consolidated proposed class action (the “Omnibus Class Action”) has been pursued on behalf of all three of the representative plaintiffs in the preceding actions; C. The plaintiffs, Todd Edward Ross, Martine Roy and Alida Satalic (the “Plaintiffs”) commenced the Omnibus Class Action in the Federal Court (Court File No. T-370-17) on March 13, 2017 by the Statement of Claim attached as Schedule “A”. -

International Association of Pride Organizers 2019 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report

International Association of Pride Organizers 2019 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report InterPride Inc. – International Association of Pride Organizers Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for organizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in the USA and is a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization under US law. It is funded by membership dues, sponsorship, merchandise sales and donations from individuals and organizations. OUR VISION A world where there is full cultural, social and legal equality for all. OUR MISSION Empowering Pride Organizations Worldwide. OUR WORK We promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride on an international level, to increase networking and communication among Pride Organizations and to encourage diverse communities to hold and attend Pride events and to act as a source of education. InterPride accomplishes it mission with Regional Conferences and an Annual General Meeting and World Conference. At the annual conference, InterPride members network and collaborate on an international scale and take care of the business of the organization. InterPride is a voice for the LGBTQ+ community around the world. We stand up for inequality and fight injustice everywhere. Our members share the latest news about their region with us, so we are able to react internationally and make a difference. Reports contained within this Annual Report are the words, personal accounts and opinions of the authors involved and do not necessarily reflect the views of InterPride as an organization. InterPride accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of material contained within. InterPride may be contacted via [email protected] or our website: www.interpride.org © 2019 InterPride Inc. -

Explicit Affects: Confession, Identity, and Desire Across Digital Platforms Brandon Arroyo a Thesis in the Mel Hoppenheim Schoo

Explicit Affects: Confession, Identity, and Desire Across Digital Platforms Brandon Arroyo A Thesis In The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Film and Moving Image Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2018 © Brandon Arroyo, 2018 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Brandon Arroyo Entitled: Explicit Affects: Confession, Identity, and Desire Across Digital Platforms and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy (Film and Moving Image Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Mia Consalvo External Examiner Dr. Susanna Paasonen External to Program Dr. Monika Gagnon Examiner Dr. Marc Steinberg Examiner Dr. Erin Manning Thesis Supervisor Dr. Thomas Waugh Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina, Graduate Program Director November 13, 2018 Dr. Rebecca Taylor Duclos, Dean Faculty of Fine Arts iii ABSTRACT Explicit Affects: Confession, Identity, and, Desire Across Digital Platforms Brandon Arroyo, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2018 This study accounts for what happens when a gay male identity politics centered around Western state power comes in contact with a pornographic aesthetic queerly subverting the markers composing this type of identity formation. While pornography has long affirmed