Police, Journalists and Crimes of HIV Non-Disclosure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nancy Nicol Page 1 of 32 Program: Visual Arts July 1

Nancy Nicol Page 1 of 32 Program: Visual Arts July 1, 2009 CURRICULUM VITAE 1) Nancy Nicol Associate Professor Department of Visual Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts Goldfarb Centre for Fine Arts, room 237 [email protected] 2. DEGREES 1977 Master of Fine Arts, York University 1974 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Sir George Williams (Concordia University) 3. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 1995 – Associate Professor, Visual Arts Dept., FFA, York University 2000 - 03 Graduate Programme Director, MFA Programme in Visual Arts 1989 - 95 Assistant Professor, Visual Arts Dept., FFA, York University 1989 Appointment to Graduate Faculty, MFA program 1988 - 89 Instructor, Castle Frank High-School and South Central School of Commerce, Continuing Education, Toronto Board of Education 1983 - 88 Instructor, Inner City Angels (Art programs in public schools) Instructor, `Artists in the Schools Program', The Ontario Arts Council 1983 Course director, video art, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, (summer) 1982 - 83 Course director: Interdisciplinary studio, Visual Arts Dept., FFA, York University 1980 - 81 Course director: printmaking, Visual Arts Dept., Fanshaw College, London 1979 - 80 Course director: drawing, Mohawk College, Hamilton 1976 - 77 Teaching Assistant: intro studio, Dept. of Visual Arts, FFA, York University 4. HONOURS (Awards/Prizes) 2009 Short-listed for the Derek Oyston CHE Film Prize, for One Summer in New Paltz, a Cautionary Tale, 23rd London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, British Film Institute, London, UK. 2007 Honourable Mention for Best Canadian Female Director -

From Paper, to Microform, to Digital? Serials at the Arquives: Canada's LGBTQ2+ Archives Donald W. Mcleod

From Paper, to Microform, to Digital? Serials at the ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives Donald W. McLeod Abstract The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives, founded in 1973, holds one of the largest collections of queer serials in the world, with more than ten thousand titles. Most are on paper, but formats have been evolving. Beginning in the 1980s, the ArQuives participated in small-scale microfilming projects. Microfilming of the collection increased greatly in 2005, when Primary Source Microfilm (PSM) undertook a large project to film a portion of the collection, resulting in 211 reels devoted to international gay and lesbian periodicals and newsletters. The PSM project was later repurposed and expanded by Gale Cengage, beginning in 2015, and forms part of its Archives of Sexuality and Gender online product. This paper examines the evolution of the ArQuives’ serial holdings from paper to microform to digital formats, and explores recent in-house digitization efforts and future prospects for expanding access to these materials. Résumé Les ArQuives : les archives LGBTQ2+ canadiennes, fondées en 1973, détiennent une des plus importantes collections de périodiques queer au monde, comprenant plus de dix mille titres. La majorité sont sur papier, mais les formats sont en évolution. Depuis les années 1980, les ArQuives participent à des projets de microfilmage de petite envergure. Le microfilmage a vu une augmentation importante en 2005, lorsque Primary Source Microfilm (PSM) a entrepris un grand projet consistant à microfilmer une portion de la collection, ayant pour résultat 211 bobines consacrées aux bulletins et périodiques gais et lesbiens internationaux. Par la suite, à partir de 2015, le projet PSM a été transformé et élargi par Gale Cengage, et fait maintenant partie de son produit en ligne Archives of Sexuality and Gender. -

2013-Queer-Ontario-Resource-List

Queer Ontario Resource List (Updated May 2013) Table of Contents Non-Fiction Books………………………………………………………………...2 – 39 Chapters in Books……………………………………………………………..….40 – 44 Journal Articles…………………………………………………………………...45 – 58 Journals – Special Issues…………………………………………………………58 – 61 Conference Papers………………………………………………………………..61 – 63 Biographies and Memoires……………………………………………………….63 – 69 Web-Based Publications and News………………………………………………70 – 81 Films and Documentaries………………………………………………….……...81 – 90 Like-Minded Individuals, Blogs and Organizations……………………………...90 – 91 Who We Are Queer Ontario is a provincial network of gender and sexually diverse individuals — and their allies — who are committed to questioning, challenging, and reforming the laws, institutional practices, and social norms that regulate queer people. Operating under liberationist and sex-positive principles, we fight for accessibility, recognition, and pluralism, using social media and other tactics to engage in political action, public education, and coalition-building. www.queerontario.org Page 1 of 91 Queer Ontario Resource List (Updated May 2013) Non-Fiction Books 1. Adam, B.D. (1987). The rise of a gay and lesbian movement . Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers. Although the Stonewall riots in New York City in June 1969 are generally considered the beginning of the Gay Liberation movement, "the first social movement to advance the civil rights of gay people was found in Germany in 1897." Amplifying John Lauritsen and David Thorstad's excellent Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935) (1974), sociologist Adam reviews the social, historic, and economic conditions surrounding the development of gay rights worldwide. Using secondary sources, he interweaves individuals, episodes, and examples into an overall picture, chronicling the fits and starts of lesbian and gay rights movements to the present. An extensive list of references supplements the annotated selected bibliography of this comprehensive international history. -

Federal Court Final Settlement Agreement 1

1 Court File No.: T-370-17 FEDERAL COURT Proposed Class Proceeding TODD EDWARD ROSS, MARTINE ROY and ALIDA SATALIC Plaintiffs - and - HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Defendant FINAL SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT WHEREAS: A. Canada took action against members of the Canadian Armed Forces (the "CAF"), members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (the "RCMP") and employees of the Federal Public Service (the “FPS”) as defined in this Final Settlement Agreement (“FSA”), pursuant to various written policies commencing in or around 1956 in the military and in or around 1955 in the public service, which actions included identifying, investigating, sanctioning, and in some cases, discharging lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender members of the CAF or the RCMP from the military or police service, or terminating the employment of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender employees of the FPS, on the grounds that they were unsuitable for service or employment because of their sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression (the “LGBT Purge”); B. In 2016, class proceedings were commenced against Canada in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, the Quebec Superior Court and the Federal Court of Canada in connection with the LGBT Purge, and those proceedings have been stayed on consent or held in abeyance while this consolidated proposed class action (the “Omnibus Class Action”) has been pursued on behalf of all three of the representative plaintiffs in the preceding actions; C. The plaintiffs, Todd Edward Ross, Martine Roy and Alida Satalic (the “Plaintiffs”) commenced the Omnibus Class Action in the Federal Court (Court File No. T-370-17) on March 13, 2017 by the Statement of Claim attached as Schedule “A”. -

Rosanne Johnson

More at dailyxtra.com facebook.com/dailyxtra @dailyxtra #560 FEB 12–25, 2015 FREE CIRCULATION AUDITED 20,000 $20 is all it takes to start saving for our retirement. Whether it’s $20 a week, $20 a day or even $20 a pay, it’s easy to start saving. $20 can get you a car wash. Or some snacks at the movies. It can also start to make your retirement dreams come true. That’s the beauty of saving with TD. With just $20 a week, $20 a day or even $20 a pay, you’ll start to see your retirement savings grow. $20 isn’t a lot. But at TD, it can be the start of something big. Visit a branch or TDStartSaving.com ® The TD logo and other trade-marks are the property of The Toronto-Dominion Bank. 2 FEB 12–25, 2015 XTRA! 21 YEARS OF HEADLINES Doctor denies lesbians sperm Preview Issue, July 30, 1993 BIGGER PRESENCE. STRONGER VOICE. Breaking news. More impact. Global outlook. Local action. Join us @DailyXtra.com PREVIEW OF DAILY XTRA MOBILE (LAUNCHING SOON) (LAUNCHING MOBILE XTRA PREVIEW OF DAILY Book seizures an international embarrassment Issue 21, June 3, 1994 XTRA! FEB 12–25, 2015 3 4 FEB 12–25, 2015 XTRA! 21 YEARS OF HEADLINES AIDS memorial proposed Issue 51, July 27, 1995 XTRA VANCOUVER’S Published by Pink Triangle Press GAY & LESBIAN NEWS PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ROSANNE JOHNSON Brandon Matheson #560 FEB 12–25, 2015 Roundup EDITORIAL Counselling Service MANAGING EDITOR Robin Perelle STAFF REPORTER Natasha Barsotti COPY EDITOR Lesley Fraser “Committed to enhancing the lives EVENT LISTINGS [email protected] and relationships of LGBTQ individuals” CONTRIBUTE OR INQUIRE about Xtra’s editorial BELLE ANCELL content: [email protected] EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE [email protected] | (604) 319-2345 Hannah Ackeral, belle ancell, David P Ball, Niko Bell, Nathaniel Christopher, Adam WWW.ROSANNEJOHNSON.COM Coish, Tom Coleman, Tyler Dorchester, Evan Eisenstadt, David Ellingsen, Jeremy Hainsworth, Chris Howey, John Inch, Pat Johnson, Joshua McVeity, Jake Peters, Raziel Reid, Pega Ren, Janet Rerecich If you can flip your partner.. -

PREVENTION REVIVED: Evaluating the Assumptions Campaign © 2005 AIDS Vancouver

PREVENTION REVIVED: Evaluating the Assumptions Campaign © 2005 AIDS Vancouver Authors of this Report: Terry Trussler and Rick Marchand Community Based Research Centre Report Design: Burkhardt Members of the National Advisory Team 2004 Campaign: Robert Allan, AIDS Coalition of Nova Scotia, Halifax Robert Rousseau, Action Séro-Zéro, Montréal Ken Monteith, AIDS Community Care Montreal (ACCM), Montréal Shaleena Theophilus & Darren Fisher, Canadian AIDS Society John Maxwell, AIDS Committee of Toronto Art Zoccole, 2 Spirited People of the 1st Nations, Toronto Mike Payne & Jeremy Johnson, Nine Circles Community Health Centre, Winnipeg Robert Smith, HIV Edmonton, Edmonton Evan Mo, Asian Society for the Intervention of AIDS (ASIA) Olivier Ferlatte, AIDS Vancouver Project Manager: Phillip Banks, AIDS Vancouver Campaign Development: Raul Cabra, Cabra Diseno Andy Williams SF AIDS Foundation Cohort Evaluation Study: Tom Lampinen, Vanguard Cohort Study, BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS Liviana Calzavara & Wendy Medved, Polaris Cohort Study, University of Toronto Think-again.ca Webmaster: Rachel Thompson, AIDS Vancouver Translation: Murielle McCabe Translations; Nestor Systems Program Consultant: Patti Murphy, HIV/AIDS Division, Public Health Agency of Canada Thank you to all the businesses, community agencies, individuals in communities across the country that supported the HIV prevention campaign for gay men. Thank you to all the gay men who participated in the national evaluation survey. Your responses have helped us shape the next campaign. Production -

Final Resource Kit April 11

Resource Kit For Parents, Educators & Service Providers Working with LGBTTQ parents and their children Creating LGBTTQ-friendly learning spaces for children aged 0-12 Updated in 2010 Resource Kit The Around the Rainbow Resource Kit accompanies the Toolkit for LGBTTQ Parents and Guardians and the Toolkit for Educators and Service Providers. It offers additional tools, handouts and resources to parents, educators and service providers to support the creation of inclusive spaces for gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans, two spirit and queer parents and their children. There are countless resources to draw upon, particularly when we consider web-based information. What we have included here is by no means exhaustive but we hope it will serve as a starting place. An invitation to Help Build Community Resources! We are interested in what you learn and experience in working on these issues. If you find a resource that is not listed here, or if you have ideas, comments or stories to include, please contact the project and we will do our best to share with others. Contact Around the Rainbow Project at: [email protected] or call 613-725-3601. Copyright © 2006 by Family Services a la famille Ottawa. All rights reserved. No part of this toolkit may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or by any information storage or retrieval system, except for personal use, without permission in writing from the Family Services à la famille Ottawa. The Around the Rainbow project is funded in part by the Counseling Foundation of Canada and the Ontario Trillium Foundation. -

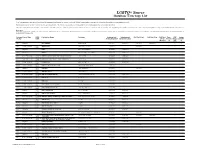

LGBTQ+ Source Database Coverage List

LGBTQ+ Source Database Coverage List "Core" coverage refers to sources which are indexed and abstracted in their entirety (i.e. cover to cover), while "Priority" coverage refers to sources which include only those articles which are relevant to the field. This title list does not represent the Selective content found in this database. The Selective content is chosen from thousands of titles containing articles that are relevant to this subject. *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverag Source Type ISSN / Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Full Text Peer- PDF Image e Policy ISBN Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Delay Review Images QuickVie (Months) ed (full w page) Core Magazine 411 Magazine Window Media 10/26/2006 11/13/2009 10/26/2006 11/13/2009 Y Y Core Academic Journal 1046- ABNF Journal Tucker Publications, Inc. -

SAME-SEX MARRIAGE in CANADA and the Thelory of POLITICAL-CULTURAL FORMATION

SAME-SEX MARRIAGE IN CANADA AND THE THElORY OF POLITICAL-CULTURAL FORMATION Susan Grove B. A., Simon Fraser University, 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology O Susan Grove 2006 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2006 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Susan Grove Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Same-Sex Marriage in Canada and the Theory of Political-Cultural Formation Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Dara Culhane Dr. Gerardo Otero Senior Supervisor Professor of Sociology Simon Fraser University Dr,,Dany Lacombe Member Associate Professor of Sociology Simon Fraser University Dr. Ian Angus External Examiner Professor of Humanities Simon Fraser University Date DefemdedlApproved: 22 March 2006 SIMON FRASER UN~VERS~W~ibra ry DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep cr make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Curriculum Vitae Toronto, ON, Canada [email protected]; [email protected]

1 KATE REID - Curriculum Vitae Toronto, ON, Canada [email protected]; [email protected] www.katereid.net I. EDUCATION_______________________________________________________________________ Degrees Doctor of Philosophy Ontario Institute for Studies in Education - Toronto, ON Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning Title of dissertation: Music to Our Ears: Using Queer Folk Song Pedagogy to do Gender and Sexuality Education 2020 Master of Arts University of British Columbia - Vancouver, BC Institute for Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Social Justice Title of thesis: Singing Queer: Archiving and Constructing a Lineage Through Song 2015 Bachelor of Education University of British Columbia - Castlegar, BC West Kootenay Teacher Education Program 2000 Baccalaureate in Arts University of Guelph, Guelph, ON College of Social and Applied Human Sciences 1997 II. CERTIFICATIONS___________________________________________________________________ Ontario Certified Teacher Ontario College of Teachers - Toronto, ON 2017-present British Columbia Certified Teacher British Columbia College of Teachers - Vancouver, BC 2000-2016 III. TRAINING________________________________________________________________________ 2 University of Toronto – Toronto, ON Workshop: How to Talk to Your Students About Mental Health: Train the Trainer November 1, 2019 Participated in a 6-hour workshop facilitated by Margeaux Feldman (www.margeauxfeldman.com) Learned approaches for discussing mental well-being, and how to talk with students at the post- secondary -

Cary Grant Pumpjack Expanding Dx Travel

FREE 20,000 AUDITED CIRCULATION VANCOUVER’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS 2014 16–29, JAN #532 PROUD LIFE: @dailyxtra CARY GRANT E 8 PUMPJACK SACKED EXPANDING Former punter facebook.com/dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra E 9 Chris Kluwe says homophobia cut short DX TRAVEL: his NFL career dailyxtra.com dailyxtra.com LAS VEGAS E10 E 22 More at at More 2 JAN 16–29, 2014 XTRA! VANCOUVER’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS XTRA VANCOUVER’S Published by Pink Triangle Press GAY & LESBIAN NEWS PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brandon Matheson www.westend-dentist.ca #532 JAN 16–29, 2014 Roundup EDITORIAL MANAGING EDITOR Robin Perelle STAFF REPORTER Natasha Barsotti COPY EDITOR Lesley Fraser EVENT LISTINGS [email protected] NIKO BELL NIKO CONTRIBUTE OR INQUIRE about Xtra’s editorial content: [email protected] EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE Victor Bearpark, Niko Bell, Tom Coleman, Tyler Dorchester, Jacques Gaudet, Danny Glenwright, Shauna Lewis, James Loewen, Ash McGregor, Kevin Dale McKeown, Raziel Reid, Yuki Shirato, The Canadian Press/Bob Leverone, The Canadian Press/ Genevieve Ross, Dave Yin ART & PRODUCTION CREATIVE DIRECTOR Lucinda Wallace GRAPHIC DESIGNERS Darryl Mabey, Bryce Stuart, Landon Whittaker ADVERTISING ADVERTISING & SALES DIRECTOR Ken Hickling NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Jeff rey Hoff man DISPLAY ADVERTISING Corey Giles, Teila Smart CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING Jessie Bennett ADVERTISING COORDINATOR Lexi Chuba DISPLAY ADVERTISING Call 604-684-9696 FESTIVAL or email [email protected]. LINE CLASSIFIEDS Call 604-684-9696 or email classifi [email protected]. The publication of an ad in Xtra does not mean that Xtra endorses the advertiser. Whistler funding Storefront features are paid advertising content. -

OTTAWA’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS 2013 11, 7–DEC NOV #261 @Dailyxtra

FREE 15,000 AUDITED CIRCULATION OTTAWA’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS 2013 11, 7–DEC NOV #261 @dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra THE NEW LEATHER Ottawa’s thriving kink scene is embracing a younger, dailyxtra.com dailyxtra.com more diverse demographic E24 More at at More 2 NOV 7–DEC 11, 2013 XTRA! OTTAWA’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS 613.216.6076 | www.eyemaxx.ca MORE AT DAILYXTRA.COM XTRA! NOV 7–DEC 11, 2013 3 XTRA Published by Pink Triangle Press PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brandon Matheson EDITORIAL ADVERTISING Want to be sure Fifi is forever MANAGING EDITOR ADVERTISING & SALES DIRECTOR Ken Hickling Danny Glenwright NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Jeffrey Hoffman COPY EDITOR Lesley Fraser ACCOUNT MANAGER Lorilynn Barker EVENT LISTINGS [email protected] NATIONAL ACCOUNTS MANAGER Derrick Branco kept in the style to which CONTRIBUTE OR INQUIRE about Xtra’s editorial CLIENT SERVICES & ADVERTISING content: [email protected] ADMINISTRATOR Eugene Coon EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE ADVERTISING & DISTRIBUTION Zara Ansar, Adrienne Ascah, Natasha Barsotti, COORDINATOR Gary Major she has become accustomed? Antonio Bavaro, Nathaniel Christopher, Julie DISPLAY ADVERTISING Cruikshank, Chris Dupuis, Philip Hannan, Matthew [email protected], 613-986-8292 Hays, Andrea Houston, Derek Meade LINE CLASSIFIEDS classifi[email protected] ART & PRODUCTION The publication of an ad in Xtra does not mean CREATIVE DIRECTOR that Xtra endorses the advertiser. Lucinda Wallace SPONSORSHIP & BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT GRAPHIC DESIGNERS Erica