Journal of Adivasi and Indigenous Studies (JAIS) Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rushil Decor Limited

RED HERRING PROSPECTUS Date: 8th June 2011 Please read Section 60B of the Companies Act, 1956 100% Book Built Issue RUSHIL DECOR LIMITED (Our Company was incorporated on May 24, 1993 as “Rushil Decor Private Limited” under the provisions of the Companies Act, 1956 with Registrar of Companies, Gujarat, Dadra & Nagar Haveli and subsequently, the name of our Company changed to “Rushil Decor Limited” on December 4, 2007 vide a fresh certificate of incorporation on becoming a public limited company. Our company has been allocated Corporate Identification number U25209GJ1993PLC019532 For details of changes in our registered office, see the section “History and Other Corporate Matters” beginning on page no 142 of this Red Herring Prospectus) REGISTERED OFFICE: S.No. 125, Near Kalyanpura Patia, Gandhinagar Mansa Road, Village Ilta, Tal: Kalol, District: Gandhinagar – 382845 Gujarat, India, Tel. No. + 91 – 2764 – 287 487, 287 777; Fax No. + 91 – 2764 – 287 700; Website: www.virlaminate.com; Email: [email protected]; Corporate Office: 1, Krinkal Apartment, Opp. Mahalaxmi Temple, Near Mahalaxmi Char Rasta, Paldi, Ahmedabad – 380 007, Gujarat, India Tel No: +91-79-2665 1346/ 2662 2 323; Fax No: +91-79-2664 0969; Email id: [email protected]; Company Secretary & Compliance Officer: Mr. Hasmukh Kanubhai Modi PROMOTERS OF THE COMPANY: MR. GHANSHYAMBHAI AMBALAL THAKKAR, MR. KRUPESH GHANSHYAMBHAI THAKKAR, GHANSHYAMBHAI A. THAKKAR (HUF), KRUPESH THAKKAR (HUF), MRS. KRUPA KRUPESH THAKKAR AND RUSHIL INTERNATIONAL Public Issue of56,43,750 Equity Shares of `. 10/- each of Rushil Decor Limited (Hereinafter referred to as the “Company” or “Issuer” or “RDL”) at a price of `.[•] per Equity Share for cash aggregating ` [•] lakh (hereinafter referred to as the “Issue”) including Promoter’s Contribution of 2,43,750 Equity Shares of ` . -

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Special Report on Ahmedabad City, Part XA

PRG. 32A(N) Ordy. 700 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PAR T X-A (i) SPECIAL REPORT ON AHMEDABAD CITY R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PRICE Rs. 9.75 P. or 22 Sh. 9 d. or $ U.S. 3.51 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: * I-A(i) General Report * I-A(ii)a " * I-A(ii)b " * I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :\< I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey .\< I-C Subsidiary Tables -'" II-A General Population Tables * II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) * II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) * II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :l< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) * IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments * IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables :\< V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) ** VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat * VII-B Fairs and Festivals * VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration " ~ N ~r£br Sale - :,:. _ _/ * VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation ) :\' IX Atlas Volume X-A Special Report on Cities * X-B Special Tables on Cities and Block Directory '" X-C Special Migrant Tables for Ahmedabad City STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS * 17 District Census Handbooks in English * 17 District Census Handbooks in Gl~arati " Published ** Village Survey Monographs for SC\-Cu villages, Pachhatardi, Magdalla, Bhirandiara, Bamanbore, Tavadia, Isanpur and Ghclllvi published ~ Monographs on Agate Industry of Cam bay, Wood-carving of Gujarat, Patara Making at Bhavnagar, Ivory work of i\1ahllva, Padlock .i\Iaking at Sarva, Seellc l\hking of S,v,,,-kundb, Perfumery at Palanpur and Crochet work of Jamnagar published - ------------------- -_-- PRINTED BY JIVANJI D. -

SRFDCL Presentation

Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Sabarmati Riverfront A Catalyst for Ahmedabad’s Economic Growth Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Urbanization is the defining phenomenon of the 21st century Globally, an unprecedented Pace & Scale of Urbanization Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River For the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities 90% of urban growth is taking place in the developing world UN World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects Cities are Engines of Economic Growth •Economic growth is associated with Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River agglomeration • No advanced country has achieved high levels of development w/o urbanizing •Density is crucial for efficiency in service delivery and key to attracting investments due to market size •Urbanization contributes to poverty reduction UN World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects Transformational Urbanism Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River 1. The logic of economic geography 2. Well-planned urban development – a pillar of economic growth Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Living close to work can encourage people to walk and cycle or use public transport. Makes the private vehicle less popular. Makes the city healthy Advantage Gujarat Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River 6% of India’s Geographical 5% of India’s population: Area: -

Day Date :- 18Th and Tr9th April, 2019

Surendra Singh,IFS STATE LEVEL ENVIRONT\,I ENT Member Seeretary IMPACT ASSESSMENT SELd.A, Bihar AUTIIORITY" BIHAR ( r;aiz r-ri LetterNo.- 90 Patna, Dated- Ll. 04 'L9 I{OTICE andr A meeting of SEIAA shall be held on 13th 19th April, 2019" All the Honaurable Members are requested to make it convenient to attend the meeting at the venue & time mentioned below: Day :- Thursday amd Friday Date :- 18th and tr9th April, 2019 Time :- lSth April (4:00 PM onward) and 19th April (1 1:00 AM onward) Venue :- Chairman's Chamber 2no Floor, Beltron Bhawan, Shastri Nagar, Patna-23 Agenda o I" Proposed Expansion of Induction Furnace & Rolling Unit (from 1,09,100 TPA to 1"66,320 TPA) Located at Sabalpur, Deedarganj, Patna , Bihar by N,4/s Neelkamal Steels Pvt" Ltd., (tISPL), (Proposal No" - SIA/3(a)/6A3ft9)" Online Proposal,No":- SIA/BR/IND/30735/20X8)" o 2" Garsanda Sand Ghat on Kiul River of District- Jamui, Area - 24 Ha (File No. SIA/1 (a)/55811 8). O nline Proposal No. : - SIA/BR/MIN/3096 1/2 0 I 9). 3. Kendua Balu Ghat on Barnar River of District- Jamui, Area - 23 Ha (File No. SIA/1 (a)/559/1 : 8). On line Proposal No" - SIA./BR/MIN/3 09 68 /2019) " 4" Sono Balu Ghat on Barnar River of District- Jamui, Area - 2I Ha (File No. - SIAI1(a)/561/1S). : Online Proposal No" - SIA,/BR/MIN/3 I 0 27 /2019\ " 5" Smarak Sand Ghat on Kiul River of District- Jamui, Area - 22 Ha (File No" - SIA/1(a)/563/1S). -

PL Details Unpaid Unclaimed Dividend 2010-11.Xlsx

PAUSHAK LIMITED - DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED / UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2011-12 AS ON 6TH AUGUST, 2018 Investor First Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father / Father / Father / Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP Id-Client Id- Investment Type Amount Proposed Name Husband Husband Husband Account Number transferred Date of transfer to First Middle Last IEPF(DDMONYYYY) Name Name Name AMBALAL RANCHHODBHAI PATEL NA NA NA 55 KRUSHNAKUNJ ATMAJYOTI NAGAR HSG SOC - OPP GUJ HSG INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA 390007 0004954 Amount for unclaimed and 2 06-SEP-2019 BOARD ELLORAPARK VADODARA 390007 unpaid dividend AHMED ADAMBHAI PATEL NA NA NA NEAR MUSJID AKOTA BARODA 390005 INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA 390005 0004957 Amount for unclaimed and 6 06-SEP-2019 unpaid dividend ASHVINKUMAR BAPULAL JOSHI NA NA NA VADA FALIA GHEE KANTA ROAD RAOPURA BARODA 390001 INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA 390001 0004958 Amount for unclaimed and 2 06-SEP-2019 unpaid dividend AMBALAL MANSUKHRAM SHAH NA NA NA BAJWADA VAYU DEVTA S STREET BARODA-390001 INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA 390001 0004959 Amount for unclaimed and 2 06-SEP-2019 unpaid dividend AMBALAL KESURBHAI PATEL NA NA NA AT POST KANDARI TA KARAJAN DIST BARODA PIN 391210 INDIA GUJARAT KARJAN 391210 0004960 Amount for unclaimed and 2 06-SEP-2019 unpaid dividend ATUL RAMANLAL DESAI NA NA NA 8 DAXA SOCIETY NIZAMPURA BARODA 390002 INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA 390002 0004961 Amount for unclaimed and 6 06-SEP-2019 unpaid dividend ALOIS LALJIBHAI RATHOD NA NA NA BEHIND HARINAGAR SOCIETY DHARMPURA T B HOSPITAL RD INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA -

Bihar. Area - 30.50 Ha (File No

Kamaljeet Singh, tns STATE LDVEL ENVIRONMI'NT Nlember Secretary IMPACT ASSESSMEN'I SEIAA" Bihar AUTHORITY, BIHAR LetterNo.- 299 Fatna,Dated- tsitoltg NOTICE A meeting of SEIAA shall be held on Wednesday & Thursday, l6th &. l7th October, 2019" All the F{onourable Members are requested to make it eonvenient to attend the meeting at the venue & time mentioned below: Day :- Wednesday & Thursday Date :- I6th & l7'h octob er,2ol9 Time :- 4:00 PM onward. Venue :- Chairman's Chamber 2nd Floor, Beltron Bhawan, Shastri Nagar, patna-23 Agenda t6-10-2019 (Wednesdav) o the followings:- 1. Sand Mining Project on Falgu river at Alipur Glrat of District- Gaya, State- Bihar, Area - 30.05 Ha (File No" - SIA/1(a)1323/16), Online propos:rl No.: -SAVBRIVIIN/I790212016). 2" Sand Mining Project on Shanti Nagar Ghat (Stretch2 of Block -l l) of District:- Gaya, State:- Bihar. Area - 30.50 Ha (File No. - SIA/l(a) l44l/17), Online Proposal No. : - s rA/B RA{IN I t7 9 2s I 20 | 6',). 3. Sand Mining Project on Bajitpur Ghat (Stretch 4, Block - 2) of District:- Gaya, State:- Bihar, Area - 30 Ha (File No. - SIA/l(a)/439117),, Online proposal No.:- SIA/BR/MIN/I7918/2016)" o 4" SHRI RAM JANAKI MEDICAL COLLEGE AND HOSPITAL, Village:- Narghoghi, Tehsil:- Sarairanian, District:- Samastipur, Bihar Total Plot Area:- 85,652 m2. Total Build-up Area:- 1,74,?titi ? l4 n1' (illl+ No. - slA/t(u)/b9J/l!r)" untino propooal No"r SIA,rBRiTvtISi I I 5 I riSiltf I e)" 5. Sand Mining Project on river Kiul at Kishanpur Sand Ghat of Lakhisarai rdistrict, Area - 23 Ha (Proposal No. -

Self Study Report for Re-Accreditation 2Nd Cycle

L.D.ARTS COLLEGE SELF STUDY REPORT FOR RE-ACCREDITATION 2ND CYCLE (SEPTEMBER – 2014) L.D.ARTS COLLEGE (ESTABLISHED: 1937) HARGOVANDAS CAMPUS, COMMERCE SIX ROADS, NAVRANGPURA, AHMEDABAD, GUJARAT, PIN - 380 009. MANAGED BY AHMEDABAD EDUCATION SOCIETY SELF STUDY REPORT FOR RE- ACCREDITATION 2nd cycle TEL.: 079-26302260, 079-26306619 FAX: 079-26302260 Web: www.ldarts.org Email: [email protected] Page No. Table of Contents A. Executive Summary 1 B. Profile of the College 4 C. Criteria-wise Inputs Criterion I: Curricular Aspects 1.1 Curriculum Planning and Implementation 15 1.2 Academic Flexibility 21 1.3 Curriculum Enrichment 25 1.4 Feedback System 35 Criterion II: Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 2.1 Admission Process, Student Enrolment And Profile 37 2.2 Catering student Diversity 42 2.3 Teaching Learning process 47 2.4 Teaching Quality 57 2.5 Evaluation Process and Reforms 70 2.6 Student performance and learning outcomes 76 Criterion III: Research, Consultancy and extension 3.1 Promotion of Research 83 3.2 Resource Mobilization for Research 89 3.3 Research Facilities 94 3.4 Research Publications and Awards 96 3.5 Consultancy 101 3.6 Extension Activities and Institutional Social 102 Responsibility (ISR) 3.7 Collaboration 111 Criterion IV: Infrastructure and Learning resources 4.1 Physical Facilities 117 4.2 Library as a Learning Resource 124 4.3 IT Infrastructure 131 4.4 Maintenance of Campus Facilities 134 Criterion V: Student Support and progression 5.1 Student Mentoring and Support 137 5.2 Student Progression 149 5.3 Student Participation and Activities 151 Criterion VI: Governance, Leadership and Management 6.1 Institutional Vision and Leadership 160 6.2 Strategy Development and Deployment 164 6.3 Faculty Empowerment Strategies 170 6.4 Financial Management and Resource Mobilization 172 6.5 Internal Quality Assurance System (IQAS) 176 Criterion VII: Innovations and Best practices 7.1 Environment Consciousness 181 7.2 Innovations 182 7.3 Best Practices 182 Evaluative Report of the Departments 1. -

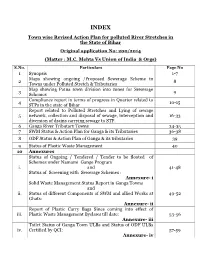

Town Wise Revised Action Plan for Polluted River Stretches in the State of Bihar Original Application No: 200/2014 (Matter : M.C

INDEX Town wise Revised Action Plan for polluted River Stretches in the State of Bihar Original application No: 200/2014 (Matter : M.C. Mehta Vs Union of India & Orgs) S.No. Particulars Page No 1 Synopsis 1-7 Maps showing ongoing /Proposed Sewerage Scheme in 2 8 Towns under Polluted Stretch & Tributaries Map showing Patna town division into zones for Sewerage 3 9 Schemes Compliance report in terms of progress in Quarter related to 4 10-15 STPs in the state of Bihar Report related to Polluted Stretches and Lying of sewage 5 network, collection and disposal of sewage, interception and 16-33 diversion of drains carrying sewage to STP. 6 Ganga River Tributary Towns 34-35 7 SWM Status & Action Plan for Ganga & its Tributaries 36-38 8 ODF Status & Action Plan of Ganga & its tributaries 39 9 Status of Plastic Waste Management 40 10 Annexures Status of Ongoing / Tendered / Tender to be floated of Schemes under Namami Gange Program i. and 41-48 Status of Screening with Sewerage Schemes : Annexure- i Solid Waste Management Status Report in Ganga Towns and ii. Status of different Components of SWM and allied Works at 49-52 Ghats: Annexure- ii Report of Plastic Carry Bags Since coming into effect of iii. Plastic Waste Management Byelaws till date: 53-56 Annexure- iii Toilet Status of Ganga Town ULBs and Status of ODF ULBs iv. Certified by QCI: 57-59 Annexure- iv 60-68 and 69 11 Status on Utilization of treated sewage (Column- 1) 12 Flood Plain regulation 69 (Column-2) 13 E Flow in river Ganga & tributaries 70 (Column-4) 14 Assessment of E Flow 70 (Column-5) 70 (Column- 3) 15 Adopting good irrigation practices to Conserve water and 71-76 16 Details of Inundated area along Ganga river with Maps 77-90 17 Rain water harvesting system in river Ganga & tributaries 91-96 18 Letter related to regulation of Ground water 97 Compliance report to the prohibit dumping of bio-medical 19 98-99 waste Securing compliance to ensuring that water quality at every 20 100 (Column- 5) point meets the standards. -

'Sisters Under the Skin'

Special articles ‘Sisters under the Skin’ Events of 2002 and Girls’ Education in Ahmedabad Even after the immediate violence has ceased, communal tension continues to exercise a vitiating influence on citizens and everyday modes of existence. This article looks at two girls’ schools in Ahmedabad, one sited in a Muslim locality and the other in a mixed dalit-Muslim populated neighbourhood, to study the impact of the events of 2002 on education. Fear and a history of violence have fostered antagonisms among different communities, while diminishing job opportunities and poverty imply that education opportunities, once available for girls, no longer exist. Denial of education, in turn, perpetuates illiteracy and trends towards an early marriage. The policies of a state government that sees communities as political votebanks have done little to restore amity between communities and faith in the state’s “secular” credentials. SUCHITRA SHETH, NINA HAEEMS he events of 2002 in Gujarat have generally perceived as is located did not directly experience violence during 2002. The acts of state-supported violence directed against Muslims paper is also informed by the authors’ first-hand experience of Twhich included mass murder, sexual abuse and large-scale having lived in Ahmedabad for the past two decades and being destruction of property. Without doubt, this was the principal eyewitnesses to the events of 2002. tragedy that left scars on the entire Muslim community. Yet, if The study uncovered many facets of what it means to be we look beyond, the violence has implications for society in a young girl in Ahmedabad and what it is like to be the mother Gujarat as a whole, for both Hindus and Muslims, and in par- of a young girl in Ahmedabad. -

Decent Work in Ahmedabad: an Integrated Approach

I L O A s i a - Pacific Working Paper Series Decent work in Ahmedabad: An integrated approach Darshini Mahadevia June 2012 DWT for South Asia and Country Office for India Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series Decent work in Ahmedabad: An integrated approach Darshini Mahadevia June 2012 DWT for South Asia and Country Office for India Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Copyright © International Labour Organization 2012 First published 2012 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Mahadevia, Darshini Decent work in Ahmedabad : an integrated approach / Darshini Mahadevia ; ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific ; ILO DWT for South Asia and Country Office for India. - Bangkok: ILO, 2012 xii, 54 p. (ILO Asia-Pacific working paper series) ISBN: 9789221262534 (web pdf) ILO Regional -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further.