A Building Stone Atlas of Herefordshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17 August 2018

Weekly list of Decisions made from 13 - 17 August 2018 Direct access to search application page click here http://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/searchplanningapplications Parish Ward Ref no Planning code Valid date Site address Description Applicant name Applicant Applicant Decision Decision address Organisation Date Avenbury Bishops 182357 Planning 26/06/2018 Munderfield Proposed steel portal Mr Trevor Munderfield Ian Savagar 14/08/2018 Approved with Conditions Frome & Permission Court, framed cover to an Eckley Court, Cradley Munderfield, existing silage pit Munderfield, Bromyard, Bromyard, Herefordshire, Herefordshire, HR7 4JX HR7 4JX Bodenham Hampton 181694 Listed Building 08/05/2018 Broadfield Court, Retrospective structural Mr A Shennan C/O Agent Owen Hicks 13/08/2018 Approved with Conditions Consent Bowley Lane, repairs to pitched roof Architecture Bodenham, and replacement of;flat Hereford, roof finishes Herefordshire, HR1 3LG Bromyard and Bromyard 180912 Planning 26/04/2018 Rowden Abbey, Proposed building for 3 Mr Ernie Rowden Abbey, Linton Design 14/08/2018 Approved with Conditions Winslow Bringsty Permission Winslow, loose boxes and tractor & Warrender Winslow, Bromyard, implement store Bromyard, Herefordshire, Herefordshire, HR7 4LS HR7 4LS Clehonger Stoney 182408 Full 28/06/2018 Hope Dene, Proposed conversion of Mr Nigel Davies 1 Abbey 13/08/2018 Approved with Conditions Street Householder Clehonger, existing single storey rear Cottages, Hereford, extension to 2;storey rear Clehonger, Herefordshire, extension. Hereford, HR2 9SH Herefordshire, HR2 9SH 1 Weekly list of Decisions made from 13 - 17 August 2018 Parish Ward Ref no Planning code Valid date Site address Description Applicant name Applicant Applicant Decision Decision address Organisation Date Clifford Golden 160028 Planning 21/06/2018 Upper Court To move field gateway 6 Mr Thomas Upper Court 15/08/2018 Approved with Conditions Valley North Permission Farm, Whitney-on-metres down road. -

Country Geological

NEWSLETTER No. 44 - April, 1984 : Editorial : Over the years, pen poised over blank paper, I have sometimes had a wicked urge to write an ed- itorial on the problems of writing an editorial. For this issue I was asked to consider something on the low attendances at a few recent meetings and this would have been a sad topic. In the lic1^ meantime we have had two meetings with large at- tvndances, further renewed subscriptions, and various other problems solved. This leaves your Country editor much happier, and quite willing to ask you to keep it up = Geological This issue has been devoted mainly to the two long articles on the local limestone and its n !''} Q problems, so for this time the feature "From the Papers" is omitted. Next Meeting : Sunday April 15th : Field trip led by Tristram Besterman to Warwick and Nuneaton. Meet 10.00 a.m. at the Museum, Market Place, Warwick, The Museum will be open, allowing us to see the geological displays, some of the reserve collections, and the Geological Locality Record Centre. This will be followed by a visit to a quarry exposing the Bromsgrove Sandstone (Middle Triassic). In the afternoon it is proposed to visit the Nuneaton dis- trict to examine the Precambrian-Cambrian geology, and to see examples of site conservation. Meetings are held in the Allied Centre, Green Ilan Entry, Tower Street, Dudley, behind the Malt Shovel pub. Indoor meetings commence at 8 p.m. with coffee and biscuits (no charge) from 7.15 p.m. Field meetings will commence from outside the Allied Centre unlegs otherwise arranged. -

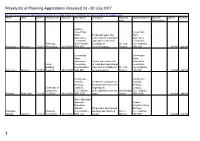

Weekly List of Planning Applications Received 24 - 30 July 2017

Weekly list of Planning Applications Received 24 - 30 July 2017 Direct access to search application page click here https://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/searchplanningapplications Parish Ward Ref no Planning code Valid date Site address Description Applicant Applicant address Applicant Easting Northing name Organisation Land at Covenhope Covenhope Farm, Proposed repair and Farm, Aymestrey, conversion of redundant Aymestrey, Leominster, agricultural cider barn Leominster, Planning Herefordshire, to;holiday let Mr John Herefordshire, Aymestrey Mortimer 172518 Permission 06/07/2017 HR6 9SY accommodation. Probert HR6 9SY 340769 264199 Covenhope Covenhope Farm, Farm, Aymestrey, Repair and conversion Aymestrey, Listed Leominster, of redundant agricultural Leominster, Building Herefordshire, cider barn to holiday;let Mr John Herefordshire, Aymestrey Mortimer 172519 Consent 06/07/2018 HR6 9SY accommodation. Probert HR6 9SY 340769 264199 Corngreave Corngreave Cottage, Certificate of lawfulness Cottage, Bosbury, for proposed conversion Bosbury, Certificate of Ledbury, of garage to Ledbury, Lawfulness Herefordshire, form;additional ancillary Mrs Marilyn Herefordshire, Bosbury Hope End 172364 (CLOPD) 14/07/2017 HR8 1QW space. Gleed HR8 1QW 367964 244023 Store Adjoining Highfield, Copwin, Brampton Goodrich, Ross Abbotts, Proposed 4 bedroomed On Wye, Brampton Planning Herefordshire, dwelling with attached Mr C J Herefordshire, Abbotts Old Gore 172512 Permission 06/07/2017 HR9 7JG garage Winney HR9 6HY 360649 226792 1 Weekly list of Planning Applications -

The Grand Re-Opening of the Parish Hall in Time Old, Yarpole Style, We Will Be Having a Tea Party for the Parish to Celebrate the Re-Opening of the Parish Hall On

Summer 2021 The Grand re-opening of the Parish Hall In time old, Yarpole style, we will be having a tea party for the Parish to celebrate the re-opening of the Parish Hall on Sunday 1st August 2 till 4pm Everyone is invited to come along and see all the improvements that have taken place over the last 12 months, the new garden, windows and redecoration. We will also have information about the Community Hub and other community groups in Yarpole. Looking forward to seeing you there. The Hall Committee Contents listing on page 2 In this issue: Yarpole Group Parish Council News-June 2021 5 Looking for a Shed 6 Footpaths on the Croft Estate 7 Would you like to be a tree warden? 8 Parish Council Annual Reports 10 Parish Council Vacancies 16 200 Club Renewal 22 The Bell-1st Birthday Party 26 St Michael Old St Peter’s Church St Leonard’s Church & All Angels Church Lucton Yarpole Croft Castle Socially distanced Community Churchyard clearing Saturday, 24th July. 1.30pm to 5pm. We need to do a first cut of the churchyard. The wild flowers have set and it is time to get rid of the invasive weeds. Bring strimmers, rakes, shears, and You! Cakes also welcome 2 Last month we received a bumper edition; here is another. This edition contains a wealth of information relating to the work of the institutions we rely on for the governance of our community. There are annual reports relating to the work of our Parish Council. These are accompanied by the monthly newsletter of the Council. -

Planning Applications Received 11 to 17 March 2013

Weekly list of Planning Applications Received 11th - 17th March 2013 Direct access to search application page click here http://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/searchplanningapplications Parish Ward Unit Ref no Planning code Valid date Site address Description Applicant Applicant Agent Agent Agent Easting Northing name address Organisation name address Aston Penyard 130558 Full 27/02/2013 Bradstocks, Replacement of Mr J Morton 5 Kilburn Kilburn 26 Harrison 368063 225014 Ingham Householder Stoney Road, 1990s extension Streathbourne Nightingale Nightingale Street, Kilcot, Newent, and Road, London, Architects Architects London, Herefordshire, refurbishment of SW17 8QZ WC1H 8JW GL18 1PB original stone;cottage. Aylton Frome 130479 Planning 18/02/2013 Newbridge Change of use Mr Wayne The Lodge, Mr Wayne The Lodge, 366633 237110 Permission Farm Park, of the former Gardner Newbridge Gardner Newbridge Aylton, Ledbury, shop building to Farm Park, Farm Park, Herefordshire, residential use Aylton, Aylton, HR8 2QG for the;owners in Ledbury, Ledbury, connection with Herefordshire, Herefordshire operation of the HR8 2QG , HR8 2QG farm park business. Ballingham Hollington 130618 Non Material 08/03/2013 Rock Cottage, Non material Mr G Dunn Bath House, Mr G Dunn Bath House, 356334 230978 Amendment Carey, amendment to Tyberton, Tyberton, Hereford, planning Hereford, Hereford, Herefordshire, permission Herefordshire, Herefordshire HR2 6NG S122428/FH HR2 9PT , HR2 9PT 1 Weekly list of Planning Applications Received 11th - 17th March 2013 Parish Ward Unit Ref no Planning -

The Parish Magazine for the Presteigne Group of Parishes Has Continued to Appear – Either Online Or in Print

Your Parish Magazine Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, the Parish Magazine for the Presteigne Group of Parishes has continued to appear – either online or in print. The parish magazine Deadline dates for Copy and Artwork For as at 28th April 2021 Presteigne With th Wednesday 19 May June issue Discoed, Kinsham, Lingen and Knill rd Wednesday 23 June July/August issue Wednesday 18th August September issue Here Is your socially-distanced but Colourful We are particularly grateful to the Town Council, our friends in Lingen, our gardener, our new weather reporter and our occasional nature-noter. We include requests for support from community groups and charities. We hope to inform and Online MERRY MONTH OF may 2021 Issue, Fa La perhaps entertain you. The Editor welcomes announcements (remember them?) and appreciates contributions from anyone and everyone from our churches and parishes, groups, schools etc. Artwork (logos, etc) should be not too complicated (one day we will be printing again in black only on a photocopier so please keep designs simple). Articles as well as artwork must be set to fit an A5 page with narrow margins. The editor reserves the right to select and edit down items for which there is insufficient space. While you may be reading this issue on screen, you can print the whole issue, or selected pages, on A4 paper in landscape to both sides (Duplex). We suggest you select ‘short-side stapling’. Note: The ‘inside’ pages have been consecutively numbered on each sheet - unlike the pages which normally make up a magazine. You are encouraged to forward this magazine to others by email or as hard copy, as above – on condition that it is neither added to, nor the text altered, in any way. -

Bishops Frome Environmental Report

Environmental Report Bishops Frome Neighbourhood Area May 2017 Bishops Frome Environmental Report Contents Non-technical summary 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Methodology 3.0 The SEA Framework 4.0 Appraisal of Objectives 5.0 Appraisal of Options 6.0 Appraisal of Policies 7.0 Implementation and monitoring 8.0 Next steps Appendix 1: Initial SEA Screening Report Appendix 2: SEA Scoping Report incorporating Tasks A1, A2, A3 and A4 Appendix 3: Consultation responses from Natural England and English Heritage Appendix 3a: Reg 14 responses to draft Environmental Report Consultation Appendix 4: SEA Stage B incorporating Tasks B1, B2, B3 and B4 Appendix 5: Options Considered Appendix 6: Environmental Report checklist Appendix 7: Feedback of Draft Environmental Report consultation (D1) Appendix 8: Screening of amended polices (D3) SEA: Task C1 (Bishops Frome) Environmental Report (May 2017) _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Non-technical summary Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is an important part of the evidence base which underpins Neighbourhood Development Plans (NDP), as it is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that environmental assets, including those whose importance transcends local, regional and national interests, are considered effectively in plan making. The Bishops Frome Parish has undertaken to prepare an NDP and this process has been subject to environmental appraisal pursuant to the SEA Directive. The Parish comprises of two main settlements of Bishops Frome itself, and Fromes Hill. Majority of the population live in these two settlements and the remainder are scattered in homes and farms throughout the parish. The parish of Bishops Frome lies approximately 9 miles north of Ledbury and four miles south of Bromyard. -

BROMYARD - HEREFORD Temporary Timetable 405 Via Cradley, Pencombe and Westhide

First LEDBURY - BROMYARD - HEREFORD Temporary Timetable 405 via Cradley, Pencombe and Westhide Wednesday only Ref.No.: WN48 Service No 405 HC W LEDBURY, Memorial . 0850 Ledbury, Rail Station . 0852 Bosbury, Bell Inn . 0911 Cradley, Finchers Corner . 0919 Cradley, Buryfields . 0922 Fromes Hill, Telephone Box . 0930 Bishops Frome, Chase Inn . 0935 Munderfield, Stocks Farm . 0939 BROMYARD, Pump Street . 0948 Bromyard, Lodon Avenue . 0953 Crowels Ash . 1002 Pencombe, Bus Shelter . 1009 Little Cowarne, Telephone Box . 1014 Ullingswick, Telephone Box . 1022 Burley Gate, A465 Roundabout . 1028 Ocle Pychard Turn . 1030 Westhide, Church . 1037 White Stone, Crossroads . 1042 Aylestone Hill, Venn's Lane Junction . 1050 Hereford, Hop Pole . 1053 HEREFORD, Shire Hall . 1055 W - Wednesdays Only HC - Financially supported by Herefordshire Council. HEREFORD - BROMYARD - LEDBURY Temporary Timetable 405 via Westhide, Pencombe and Cradley Service No 405 HC W HEREFORD, Shire Hall . 1320 Hereford, Merton Hotel . 1324 Aylestone Hill, Venn's Lane Junction . 1327 White Stone, Crossroads . 1335 Westhide, Church . 1340 Ocle Pychard Turn . 1347 Burley Gate, A465 Roundabout . 1349 Ullingswick, Telephone Box . 1352 Little Cowarne, Telephone Box . 1359 Pencombe, Bus Shelter . 1404 Crowels Ash . 1408 Bromyard, Lodon Avenue . 1416 BROMYARD, Pump Street . 1421 Munderfield, Stocks Farm . 1429 Bishops Frome, Chase Inn . 1433 Fromes Hill, Telephone Box . R Cradley, Buryfields . R Cradley, Finchers Corner . R Bosbury, Bell Inn . R Ledbury, Rail Station . 1507 LEDBURY, Market House . 1510 W - Wednesdays Only R - Sets down on request by passengers on board vehicle in Bromyard. HC - Financially supported by Herefordshire Council. First WORCESTER - LEDBURY Temporary Timetable 417 via Leigh Sinton, Cradley and Bosbury Monday to Friday (not Public Holidays) Ref.No.: WN48 Service No 417 671 417 417 417 417 HC HC HC HC HC HC NSD T NSD SD WORCESTER, Bus Station . -

Murchison in the Welsh Marches: a History of Geology Group Field Excursion Led by John Fuller, May 8 – 10 , 1998

ISSN 1750-855X (Print) ISSN 1750-8568 (Online) Murchison in the Welsh Marches: a History of Geology Group field excursion led by John Fuller, May 8th – 10th, 1998 John Fuller1 and Hugh Torrens2 FULLER, J.G.C.M. & TORRENS, H.S. (2010). Murchison in the Welsh Marches: a History of Geology Group field excursion led by John Fuller, May 8th – 10th, 1998. Proceedings of the Shropshire Geological Society, 15, 1– 16. Within the field area of the Welsh Marches, centred on Ludlow, the excursion considered the work of two pioneers of geology: Arthur Aikin (1773-1854) and Robert Townson (1762-1827), and the possible train of geological influence from Townson to Aikin, and Aikin to Murchison, leading to publication of the Silurian System in 1839. 12 Oak Tree Close, Rodmell Road, Tunbridge Wells TN2 5SS, UK. 2Madeley, Crewe, UK. E-mail: [email protected] "Upper Silurian" shading up into the Old Red Sandstone above, and a "Lower Silurian" shading BACKGROUND down into the basal "Cambrian" (Longmynd) The History of Geology Group (HOGG), one of below. The theoretical line of division between his the specialist groups within the Geological Society Upper and Lower Silurian ran vaguely across the of London, has organised a number of historical low ground of Central Shropshire from the trips in the past. One was to the area of the Welsh neighbourhood of the Craven Arms to Wellington, Marches, based at The Feathers in Ludlow, led by and along this line the rocks and faunas of the John Fuller in 1998 (8–10 May). -

The Furlong Customisable Oak Framed Homes in the Heart of the Herefordshire Countryside

The Furlong Customisable Oak Framed Homes in the heart of the Herefordshire countryside Sales Brochure Contents The Furlong Aymestrey 4 A rare opportunity 6 On your doorstep 8 Discover North Herefordshire 13 The site 18 Plot 1 20 Plot 2 22 Plot 3 24 Plot 4 26 Plot 5 28 Inspired by design 32 Oakwright’s Acorn specification 34 Our simple and trusted process 36 Your design team 38 Your build team 39 Why custom build 40 How to reserve 42 2 Custom Build Homes | The Furlong Custom Build Homes | The Furlong 3 The Furlong Aymestrey 4 Custom Build Homes | The Furlong Custom Build Homes | The Furlong 5 A rare opportunity An exclusive small development offering high quality, oak framed homes with well proportioned living spaces and large gardens. The Furlong is a high quality residential development of beautiful oak framed customisable homes situated in the idyllic rural village of Aymestrey, Herefordshire. In partnership with reputable oak frame supplier ‘Oakwrights’ and award winning A1 rated building contractor ‘G.P. Thomas’, plot purchasers are given the opportunity to customise the internal configuration and specification of their preferred home at The Furlong. Working in consultation with Oakwrights to customise the home, once agreed G.P. Thomas will then cost and build each property in its entirety to the individual needs and requirements of its future owner. This unique development comprises of five detached homes, with separate garages, each on a generously sized plot. Embark on a custom build journey at The Furlong and realise your potential to live in a home created for you. -

Aymestrey, Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 9UT Detached 3 Bed

Ballsgate House, Aymestrey, Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 9UT Detached 3 Bed. Stone & Brick Cottage in need of Refurbishment. O.I.R.O £240,000 Ballsgate House, Aymestrey Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 9UT • Detached Stone & Brick Cottage in need of Complete Scheme of Refurbishment • Entrance Hall • Kitchen • Lounge • Rear Lobby • Ground Floor Bathroom • 3 Bedrooms • Gardens to Front, Side and Rear. Steep Wooded Area to Rear • Private Water Supply & Drainage • A Range of Stone & Tin Outbuildings O.I.R.O £240,000 Freehold To arrange a viewing please contact us on t. 01568 610600 info@bill‐jackson.co.uk www.bill‐jackson.co.uk LOCATION Ballsgate House is a detached stone and brick cottage requiring a complete scheme of refurbishment but set in a charming rural position overlooking the fields to the front and all set outside the popular village of Aymestrey. Aymestrey is a rural north Herefordshire village set amidst pretty countryside and having a charming village inn and restaurant premises, a village hall and an active local community. The larger villages of Kingsland and Wigmore lie approximately 3 miles respectively and have fuller facilities to include primary schools in both villages and a well known secondary school in Wigmore. The market towns of Leominster and Ludlow are about 7 and 9 miles away respectively and are well known for their interesting range of shops and other facilities to include supermarkets. BRIEF DESCRIPTION Ballsgate House is a detached stone and brick cottage having accommodation over two storeys to include: an entrance hallway, lounge, kitchen, rear lobby and ground floor bathroom. To the first floor there is a landing and 3 bedrooms, all requiring refurbishment throughout. -

Minutes of an Ordinary Meeting

Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of Abbeydore and Bacton Group Parish Council held in Abbeydore Village Hall on Tuesday 3rd March 2020 No ABPC/MW/103 Present Councillor Mr D Watkins Chairman Councillor Mr T Murcott Vice - Chairman Councillor Mr D Bannister Councillor Mrs W Gunn Councillor Mr M Jenkins Clerk Mr M Walker Also Present PC Jeff Rouse, PCSO Pete Knight and one further member of the public The Parish Council Meeting was formally opened by the Chairman at 7.30pm 1.0 Apologies for Absence Apologies were received from Councillor Mrs A Booth, Councillor Mr D Cook, Councillor Mr R Fenton and Golden Valley South Ward Councillor Mr Peter Jinman Parish Lengthsman/Contractor Mr Terry Griffiths and Locality Steward Mr Paul Norris not present 2.0 Minutes The Minutes of the Ordinary Group Parish Council Meeting No ABPC/MW/102 held on th Tuesday 7 January 2020 were unanimously confirmed as a true record and signed by the Chairman 3.0 Declarations of Interest and Dispensations 3.1 To receive any declarations of interest in agenda items from Councillors No Declarations of Interest were made 3.2 To consider any written applications for dispensation There were no written applications for dispensation made The Parish Council resolved to change the order of business at this time to Item 7.2 7.0 To Receive Reports (if available) from:- 7.2 West Mercia Police PC Jeff Rouse Safer Neighbourhood Team reported on the following:- No recent thefts or burglaries on the patch Scams involving the elderly, vulnerable females e.g.