ACC Historiographer's Report Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice by Jonathan A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OCAD University Open Research Repository Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice By Jonathan A. Lockyer A thesis presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts, 2014 Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University Toronto, Ontario Canada, April 2014 ©Jonathan A. Lockyer, April 2014 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature __________________________________________________ ii Abstract Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice Masters of Fine Arts, 2014 Jonathan A. Lockyer Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University This thesis establishes a critical genealogy of the history of curating Indigenous art in Canada from an Ontario-centric perspective. Since the pivotal intervention by Indigenous artists, curators, and political activists in the staging of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, Quebec, the curation of Indigenous art in Canada has moved from a practice of necessity, largely unrecognized by mainstream arts institutions, to a professionalized practice that exists both within and on the margins of public galleries. -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

Indian Art in the 1990S Ryan Rice

Document generated on 09/25/2021 9:32 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review Presence and Absence Redux: Indian Art in the 1990s Ryan Rice Continuities Between Eras: Indigenous Art Histories Article abstract Continuité entre les époques : histoires des arts autochtones Les années 1990 sont une décennie cruciale pour l’avancement et le Volume 42, Number 2, 2017 positionnement de l’art et de l’autonomie autochtones dans les récits dominants des états ayant subi la colonisation. Cet article reprend l’exposé des URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042945ar faits de cette période avec des détails fort nécessaires. Pensé comme une DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1042945ar historiographie, il propose d’explorer chronologiquement comment les conservateurs et les artistes autochtones, et leurs alliés, ont répondu et réagi à des moments clés des mesures coloniales et les interventions qu’elles ont See table of contents suscitées du point de vue politique, artistique, muséologique et du commissariat d’expositions. À la lumière du 150e anniversaire de la Confédération canadienne, et quinze ans après la présentation de la Publisher(s) communication originale au colloque, Mondialisation et postcolonialisme : Définitions de la culture visuelle , du Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, il UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des V reste urgent de faire une analyse critique des préoccupations contemporaines universités du Canada) plus vastes, relatives à la mise en contexte et à la réconciliation de l’histoire de l’art autochtone sous-représentée. ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rice, R. -

Nadia Myre CV 2020

NADIA MYRE —CURRICULUM VITAE ACADEMIC BACKGROUND 2002 Master of Fine Arts, Studio Arts (specializaIon in Sculpture), Concordia University, Montreal, QC 1997 Fine Art Degree, Interdisciplinary Studio Arts, Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, Vancouver, BC 1995 Associate Degree, Studio Arts (emphasis in Sculpture and Printmaking) Camosun College, Victoria, BC OTHER EDUCATION/SPECIALIZED ATELIERS 2019 Master Class: The Arrivals Legacy Project with Diane Roberts, Kìnawind Lab, Montreal, QC 2018 Master Class: Human Specific Performance, Nullo Facchini (Cantabile 2), Centaur Scene Study, Montreal, QC Master Class: The Arrivals Legacy Project with Diane Roberts, Playwrights Workshop Montreal, Montreal, QC 2017 Interdisciplinary ArIsts Unit, Dramaturg Sarah Elkashef, Playwrights Workshop Montreal, Montreal, QC AuthenIc Movement (Tedi Tafel) NaIonal Theatre School, Montreal, QC 2016… Anishinaabemowin classes for beginners, NaIve Montreal, Montreal, QC 2015 Cree language for beginners, Dawson College, Montreal, QC DYI Electronics for ArIsts (Stephanie Castonguay) Studio XX, Montreal, QC Programming Fundamentals with Arduino (Angela Gabereau) Eastern Bloc New Media and Interdisciplinary Art, Montreal, QC 2014 Audio-Mobile: Field Recording, sound mapping (Owen Chapman and Samuel Thulin) OBORO New Media Lab, Montreal, QC First People’s Sacred Stories (FPST 323 with Dr. Elma Moses) Concordia University, Montreal, QC 2013 Poly-screen Workshop (Nelly-Eve Rajotte and Aaron Pollard) OBORO New Media Lab, Montreal, QC Audio Art: Recording and site-specific sound design 2 (Anne-Françoise Jacques) OBORO New Media Lab, Montreal, QC Algonquian Languages (FPST 310 with Manon Tremblay) Concordia University, Montreal, QC 2008 Centre de l’image et de l’éstamp de Mirabel (CIEM), 6-month full time printmaking class … 2008-09 RESIDENCIES 2019 Vermont Studio Center—Guest Faculty, Johnson, VT (invited. -

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ______

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ A Knowledge and Literature Review Prepared for the Research and Evaluaon Sec@on Canada Council for the Arts _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRANCE TRÉPANIER & CHRIS CREIGHTON-KELLY December 2011 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For more information, please contact: Research and Evaluation Section Strategic Initiatives 350 Albert Street. P.O. Box 1047 Ottawa ON Canada K1P 5V8 (613) 566‐4414 / (800) 263‐5588 ext. 4261 [email protected] Fax (613) 566‐4430 www.canadacouncil.ca Or download a copy at: http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e Cette publication est aussi offerte en français Cover image: Hanna Claus, Skystrip(detail), 2006. Photographer: David Barbour Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today: A Knowledge and Literature Review ISBN 978‐0‐88837‐201‐7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS! 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY! 4 Why a Literature Review?! 4 Steps Taken! 8 Two Comments on Terminology! 9 Parlez-vous français?! 10 The Limits of this Document! 11 INTRODUCTION! 13 Describing Aboriginal Arts! 15 Aboriginal Art Practices are Unique in Canada! 16 Aboriginal Arts Process! 17 Aboriginal Art Making As a Survival Strategy! 18 Experiencing Aboriginal Arts! 19 ABORIGINAL WORLDVIEW! 20 What is Aboriginal Worldview?! 20 The Land! 22 Connectedness! -

INDIGENOUS NEW MEDIA ART and RESURGENT CIVIC SPACE By

“REPERCUSSIONS:” INDIGENOUS NEW MEDIA ART AND RESURGENT CIVIC SPACE by Jessica Jacobson-Konefall A thesis submitted to the Cultural Studies Program In conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2015) Copyright © Jessica Jacobson-Konefall, 2015 i Abstract This dissertation investigates Indigenous new media artworks shown at Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery, located in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. I argue that Urban Shaman is an institution of Indigenous resurgence and translocal citizenship in Winnipeg. The new media artworks I examine operate as authoritative civic spaces by drawing upon Indigenous aesthetic traditions and new media technologies. The first chapter centers on new media artworks by artists Scott Benesiinaabandan (Anishinaabe) and Rosalie Favell (Métis), conveying Winnipeg’s histories through their artistic renditions of personal and public archives that frame Winnipeg’s city spaces. The chapter locates these works in conversation with artists Terril Calder (Métis) and Terrance Houle (Blood) whose new media artworks reframe and restage civic archives in Toronto and Calgary. The next chapter considers how new media artworks at Urban Shaman by Jude Norris, Nadia Myre, Jordan Bennett, and Terril Calder enact what I am calling Indigenous civic ecology, relating human and non-human elements of the city through Cree, Anishinaabe, Mi'kmaq and Métis genealogies. The final chapter discusses how new media artworks by Jason Baerg (Cree/ Métis), Rebecca Belmore (Anishinaabe), and Scott Benesiinaabandan (Anishinaabe) advance a lexicon of aesthetic values, particularly “travelling traditional knowledge” and “blood memory,” in response to globalization. This dissertation illustrates how new media artworks shown at Urban Shaman embody critical Indigenous methodologies in relationships of ongoing praxis. -

Charmaine Andrea Nelson (Last Updated 4 December 2020)

Charmaine Andrea Nelson (last updated 4 December 2020) Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada e-mail: [email protected] Website: blackcanadianstudies.com Table of Contents Permanent Affiliations - 2 Education - 2 Major Research Awards, Fellowships & Honours - 3 Other Awards, Fellowships & Honours – 4 Research - 5 Research Grants and Scholarships - 5 Publications - 9 Lectures, Conferences, Workshops – 18 Keynote Lectures – 18 Invited Lectures: Academic Seminars, Series, Workshops – 20 Refereed Conference Papers - 29 Invited Lectures: Public Forums – 37 Museum & Gallery Lectures – 42 Course Lectures - 45 Teaching - 50 Courses - 50 Course Development - 59 Graduate Supervision and Service - 60 Administration/Service - 71 Interviews & Media Coverage – 71 Blogs & OpEds - 96 Interventions - 99 Conference, Speaker & Workshop Organization - 100 University/Academic Service: Appointments - 103 University/Academic Service: Administration - 104 Committee Service & Seminar Participation - 105 Forum Organization and Participation - 107 Extra-University Academic Service – 108 Qualifications, Training and Memberships - 115 Related Cultural Work Experience – 118 2 Permanent Affiliations 2020-present Department of Art History and Contemporary Culture NSCAD, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Professor of Art History and Tier I Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement/ Founding Director - Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery: research, administrative duties, teaching (1 half course/ year): undergraduate and MA -

Technologies of Self-Fashioning: Virtual Ethnicities in New Media Art

Technologies of Self-Fashioning: Virtual Ethnicities in New Media Art Alice Ming Wai Jim Concordia University Montreal, Canada [email protected] Abstract tique and redress the former. Why? Because the bodies This paper proposes a theoretical framework with which to dis- engaged are themselves potentially disruptive, particularly cuss the critical engagement of media art projects in Second Life when it is up against hegemonic social norms and conduct, with racialized self-representation, fashion and ethnic dress. Ex- of which dress is a significant marker. One of the artistic amining Montreal-based Mohawk artist Skawennati’s machinima strategies is to facilitate the online critically-aware remedi- series, TimeTravellerTM (2008-13), a project of self- ation of ethnic apparel (the entire outfit from makeup and determination, survivance and Indigenous futurity, it argues the hairstyles to clothing and accessories—even behaviours). critically-aware act of ‘virtually self-fashioning’ racialized born- Elsewhere I have argued that ‘ethnic dress’ (and its vari- digital identities, or virtual ethnicities, disrupts ways in which ants—‘national dress’ or ‘world fashion’) exist only be- today’s vast proliferation of self-technologies enabling the crea- cause of the persistent Eurocentric perception of fashion as tion, recreation and management of multiple selves, would other- a purely Euro-American invention. ‘Ethnic apparel” is thus wise remain complicit with neoliberal colour-blind racism. used as a critical term whenever possible to underscore sartorial interventions cognizant of prevailing racist ideo- Keywords logies and discourses. The paper concludes with an explo- ration of Montreal-based Mohawk artist Skawennati’s ma- Self-fashioning, fashion, ethnic apparel, race, gender, coloublind chinima series, TimeTravellerTM (2008-13), as an example racism, Second Life, virtual worlds, SLart, Skawennati, Time of the complex processes of cultural negotiation involved Traveller in the virtual construction of “Indian Country” in Second Life. -

Rupturing Settler Time: Visual Culture and Geographies of Indigenous Futurity

World Art ISSN: 2150-0894 (Print) 2150-0908 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwor20 Rupturing settler time: visual culture and geographies of indigenous futurity Amber Hickey To cite this article: Amber Hickey (2019): Rupturing settler time: visual culture and geographies of indigenous futurity, World Art, DOI: 10.1080/21500894.2019.1621926 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2019.1621926 Published online: 28 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 9 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwor20 World Art, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2019.1621926 Research article Rupturing settler time: visual culture and geographies of indigenous futurity Amber Hickey* History of Art and Visual Culture, University of California - Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA This article focuses on the implications of the work of two artists on discourses of temporality and Indigenous futurity. I analyze the work of Skawennati and Bonnie Devine, with particular consideration of their resistance to the hegemonic temporality of extractive and capitalist lifeways and what Mark Rifkin calls ‘settler time’ [Rifkin, Mark. 2017. Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination. Durham: Duke University Press]. Skawennati provides a spiraling narrative of Indigenous pasts and futures in her machinima series, TimeTraveller™. In her sculptural installation, Letters from Home, Bonnie Devine calls upon the viewer to consider the stones from the Serpent River First Nation as elders. The casts of these stones are framed as texts, and viewers are encouraged to learn how to read these lessons, collapsing the divide between deep time and the present. -

Romance Weekend Package - 2Ppl Drama 15Th Anniversary (Fri After 6Pm, Sat & Delegate Packages + Passes Flexi Package Action Package Sun Screenings Only) Pass

NATIV E to aactionction NATIV E to Presenting Spon aactionction sor: FILM NATIVE to + MEDIA ARTS FESTI VAL OCT. 22-26, 2014 Romance imagineN Download the imagineN ATIVE Apple + AndroidATIVE App .org NATIVE to DRAMA Photo Credit: Roger Manndal WE, THE INdigENous scREEN stoRYTEllERS, UNitED IN THis NoRTHERN coRNER of ouR MotHER THE EaRTH IN A GREat assEMBLY of wisdom DEclaRE to all NatioNS WE GLORY IN OUR PAST, • when our earth was nurturing our oral traditions • when night sky evoked the visions of our dreams • when Sun and the Moon were our parents in stories told • when storytelling made us all brothers and sisters • when our stories brought forth great chiefs and leaders • when justice was upheld in the stories told. WE WILL: • Hold and manage Indigenous cultural and intellectual property. • Ensure our continued recognition as primary guardians and interpreters of our culture. • Respect Indigenous individuals and communities. • Faithfully preserve our traditional knowledge with sound and image. • Use our skills to communicate with nature and all living things. • Heal our wounds through screen storytelling. • Preserve and pass on our stories to those not yet born. We will manage our own destiny and maintain our humanity and pride as Indigenous peoples through screen storytelling. Guovdageaidnu, Sápmi, October 2011 Written by Åsa Simma (Sámi), with support from Darlene Johnson (Dunghutti), and accepted and recognized by the participants of the Indigenous Film Conference in Kautokeino, Sápmi, October 2011. Thanks to the International Sámi Film Center (Åsa Simma and Anne Lajla Utsi) for sharing this document in our Catalogue. For more information on the Center, visit www.isf.as. -

In the Balance

In the Balance In the Balance Indigeneity, Performance, Globalization Edited by Helen Gilbert, J.D. Phillipson and Michelle H. Raheja Liverpool University Press First published 2017 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2017 Liverpool University Press The right of Helen Gilbert, J.D. Phillipson and Michelle H. Raheja to be identified as the editors of this book has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 978-1-78694-034-6 paperback https://doi.org/10.3828/9781786940803 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Printed and bound in Poland by BooksFactory.co.uk Contents Contents Introduction Helen Gilbert 1 1. Inside the Machine: Indigeneity, Subversion and the Academy Michael Greyeyes 25 2. Beyond the ‘Nação mestiça’: Post-Racial Performance, Native Sovereignty and Political Community in Contemporary Brazil Tracy Devine Guzmán 45 3. Assimilating Globalization, Performing Indigeneity: Richard Loring’s African Footprint Arifani Moyo 65 4. Repatriation, Rights and the Political Lives of the Dead Margaret Werry 83 5. Indigenous Cinema, Hamlet and Québécois Melancholia Kester Dyer 105 6. Beyond the Burden in Redfern Now: Global Collaborations, Local Stories and ‘Televisual Sovereignty’ Faye Ginsburg 123 • v • In the Balance 7. Her Eyes on the Horizon and Other (un)Exotic Tales from Beyond the Reef Rosanna Raymond 143 8. -

2018 Annual Report

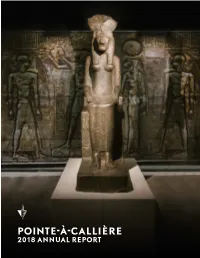

POINTE-À-CALLIÈRE 2018 ANNUAL REPORT A MUSEUM OF BUILDERS Building a culture of archaeology and history Once again Building the future Since it first opened, Pointe-à-Callière this year, Pointe-à-Callière succeeded in piquing public interest has turned the spotlight on builders from the past, making the in the history of Montréal and the world’s great civilizations. achievements of exceptional women and men and remarkable Nearly 527,000 people visited the museum, up by 14% from civilizations as widely accessible as possible. Through 2017. What’s more, a study found that 14% of visitors from our exhibitions, they have shared with us their passion, outside the city came to Montréal specifically to see Pointe- determination and humanity, all extraordinary sources of à-Callière or the Queens of Egypt exhibition. These figures inspiration for our visitors. exceeded our expectations, and we owe this success to the This year, the Museum paid tribute to the splendours of the undeniable expertise of the Museum team and the talents of Queens of Egypt. These powerful women, too often forgotten, top professionals. marked ancient Egypt with their charisma and shining In addition, the Museum received a number of prestigious intelligence. Thanks to our original perspective on this epoch awards this year, recognizing Pointe-à-Callière’s influential and the exceptional quality of the objects and digital decors in role as an entrepreneur and cultural innovator. The Société des the exhibition, Queens of Egypt attracted 316,000 visitors – an all- musées du Québec gave the Museum its Prix d’excellence for the time record for Pointe-à-Callière.