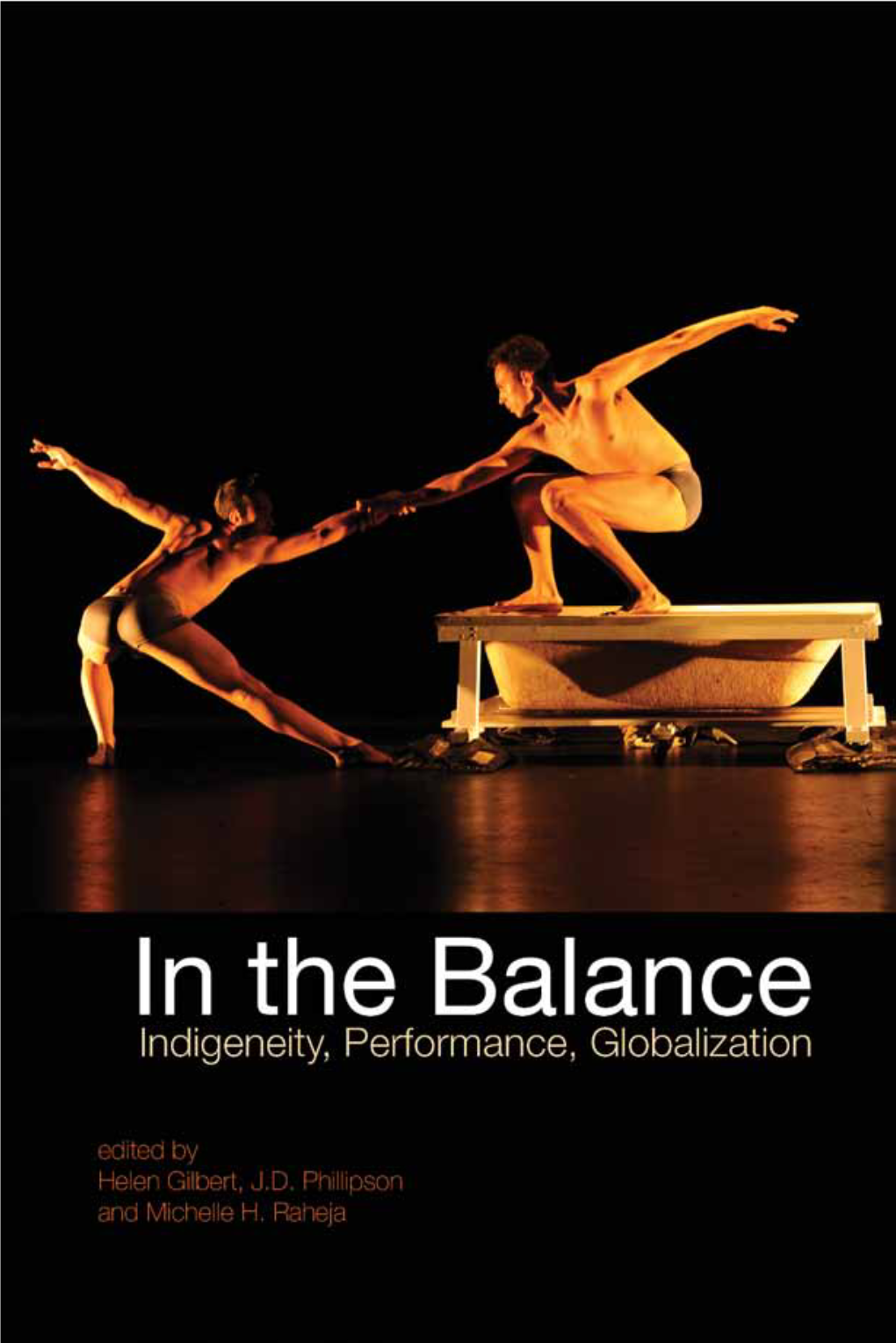

In the Balance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Balance Training on Balance Ability in Handball Players

EXERCISE AND QUALITY OF LIFE Research article Volume 4, No. 2, 2012, 15-22 UDC 796.322-051:796.012.266 THE EFFECTS OF BALANCE TRAINING ON BALANCE ABILITY IN HANDBALL PLAYERS Asimenia Gioftsidou , Paraskevi Malliou, Polina Sofokleous, George Pafis, Anastasia Beneka, and George Godolias Department of Physical Education and Sports Science, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, Greece Abstract The purpose of the present study was to investigate, the effectiveness of a balance training program in male professional handball players. Thirty professional handball players were randomly divided into experimental and control group. The experimental group (N=15), additional to the training program, followed an intervention balance program for 12 weeks. All subjects performed a static balance test (deviations from the horizontal plane). The results revealed that the 12-week balance training program improved (p<0.01) all balance performance indicators in the experimental group. Thus, a balance training program can increase balance ability of handball players, and could used as a prevent tool for lower limbs muscular skeletal injuries. Keywords: handball players, proprioception, balance training Introduction Handball is one of the most popular European team sports along with soccer, basketball and volleyball (Petersen et al., 2005). The sport medicine literature reports team sports participants, such as handball, soccer, hockey, or basketball players, reported an increased risk of traumatic events, especially to their lower extremity joints (Hawkins, and Fuller, 1999; Meeuwisse et al., 2003; Wedderkopp et al 1997; 1999). Injuries often occur in noncontact situations (Hawkins, and Fuller, 1999; Hertel et al., 2006) resulting in substantial and long-term functional impairments (Zech et al., 2009). -

The Meaning of Yaroomba II

Revisiting the place name meaning of Yaroomba The Gaiarbau, ‘bunya country’ and ‘thick vine scrub’ connections (by Kerry Jones, Arnold Jones, Sean Fleischfresser, Rodney Jones, Lore?a Algar, Helen Jones & Genevieve Jones) The Sunshine Coast region, fiHy years ago, may have had the greatest use of place names within Queensland derived from Aboriginal language words, according to researcher, E.G. Heap’s 1966 local history arQcle, ‘In the Wake of the Rasmen’. In the early days of colonisaon, local waterways were used to transport logs and Qmber, with the use of Aboriginal labour, therefore the term ‘rasmen’. Windolf (1986, p.2) notes that historically, the term ‘Coolum District’ included all the areas of Coolum Beach, Point Arkwright, Yaroomba, Mount Coolum, Marcoola, Mudjimba, Pacific Paradise and Peregian. In the 1960’s it was near impossible to take transport to and access or communicate with these areas, and made that much more difficult by wet or extreme weather. Around this Qme the Sunshine Coast Airport site (formerly the Maroochy Airport) having Mount Coolum as its backdrop, was sQll a Naonal Park (QPWS 1999, p. 3). Figure 1 - 1925 view of coastline including Mount Coolum, Yaroomba & Mudjimba Island north of the Maroochy Estuary In October 2014 the inaugural Yaroomba Celebrates fesQval, overlooking Yaroomba Beach, saw local Gubbi Gubbi (Kabi Kabi) TradiQonal Owner, Lyndon Davis, performing with the yi’di’ki (didgeridoo), give a very warm welcome. While talking about Yaroomba, Lyndon stated this area too was and is ‘bunya country’. Windolf (1986, p.8) writes about the first Qmber-ge?ers who came to the ‘Coolum District’ in the 1860’s. -

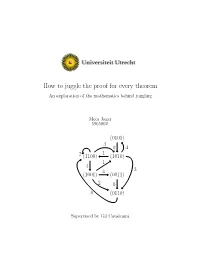

How to Juggle the Proof for Every Theorem an Exploration of the Mathematics Behind Juggling

How to juggle the proof for every theorem An exploration of the mathematics behind juggling Mees Jager 5965802 (0101) 3 0 4 1 2 (1100) (1010) 1 4 4 3 (1001) (0011) 2 0 0 (0110) Supervised by Gil Cavalcanti Contents 1 Abstract 2 2 Preface 4 3 Preliminaries 5 3.1 Conventions and notation . .5 3.2 A mathematical description of juggling . .5 4 Practical problems with mathematical answers 9 4.1 When is a sequence jugglable? . .9 4.2 How many balls? . 13 5 Answers only generate more questions 21 5.1 Changing juggling sequences . 21 5.2 Constructing all sequences with the Permutation Test . 23 5.3 The converse to the average theorem . 25 6 Mathematical problems with mathematical answers 35 6.1 Scramblable and magic sequences . 35 6.2 Orbits . 39 6.3 How many patterns? . 43 6.3.1 Preliminaries and a strategy . 43 6.3.2 Computing N(b; p).................... 47 6.3.3 Filtering out redundancies . 52 7 State diagrams 54 7.1 What are they? . 54 7.2 Grounded or Excited? . 58 7.3 Transitions . 59 7.3.1 The superior approach . 59 7.3.2 There is a preference . 62 7.3.3 Finding transitions using the flattening algorithm . 64 7.3.4 Transitions of minimal length . 69 7.4 Counting states, arrows and patterns . 75 7.5 Prime patterns . 81 1 8 Sometimes we do not find the answers 86 8.1 The converse average theorem . 86 8.2 Magic sequence construction . 87 8.3 finding transitions with flattening algorithm . -

Finnish Title Artist ID

Finnish Title Artist ID 0010 APULANTA 300001 008 (HALLAA) APULANTA 300002 12 APINAA NYLON BEAT 300003 12 APINAA NYLON BEAT 300004 1963 - VIISITOISTA VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS 305245 1963 - VIISITOISTA VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS 305246 1972 ANSSI KELA 300005 1972 ANSSI KELA 300006 1972 ANSSI KELA 300007 1972 MAIJA VILKKUMAA 304851 1972 (CLEAN) MAIJA VILKKUMAA 304852 2080-LUVULLA ANSSI KELA 304853 2080-LUVULLA SANNI 304759 2080-LUVULLA SANNI 304888 2080-LUVULLA (CLEAN) ANSSI KELA 304854 506 IKKUNAA MILJOONASADE 304793 A VOICE IN THE DARK TACERE 304024 AALLOKKO KUTSUU GEORG MALMSTEN 300008 AAMU ANSSI KELA 300009 AAMU ANSSI KELA 300010 AAMU ANSSI KELA 300011 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 300012 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 300013 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 304580 AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA 300014 AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA 304579 AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 300015 AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 300016 AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 300017 AAMUISIN ZEN CAFE 300018 AAMUKUUTEEN JENNA 300019 AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN 300020 AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN 300021 AAMULLA VARHAIN KANSANLAULU 300022 AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA 300023 AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA 304576 AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 300024 AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 300025 AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 300026 AAMUYÖ MERJA RASKI 300027 AAVA EDEA 300028 AAVERATSASTAJAT DANNY 300029 ADDICTED TO YOU LAURA VOUTILAINEN 300030 ADIOS AMIGO LEA LAVEN 300031 AFRIKAN TÄHTI ANNIKA EKLUND 300032 AFRIKKA, SARVIKUONOJEN MAA EPPU NORMAALI 300033 AI AI JUSSI TUIJA -

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa

All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 PhD Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD in Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London 2013 Cover Image: Party Goer Dancing at House Party Brixton, Johannesburg, 2005 (Author’s own) 1 Acknowledgements I owe a massive debt to a number of people and institutions who have made it possible for me to give the time I have to this work, and who have supported and encouraged me throughout. The research and writing of this project was made financially possible through a generous studentship from the ESRC. I also benefitted from the receipt of a completion grant from the Goldsmiths Anthropology Department. Sophie Day took over my supervision at a difficult point, and has patiently assisted me to see the project through to submission. John Hutnyk’s and Sari Wastel’s early supervision guided the incubation of the project. Frances Pine and David Graeber facilitated an inspiring and supportive writing up group to formulate and test ideas. Keith Hart’s reading of earlier sections always provided critical and pragmatic feedback that drove the work forward. Julian Henriques and Isaak Niehaus’s helpful comments during the first Viva made it possible for this version to take shape. Hugh Macnicol and Ali Clark ensured a smooth administrative journey, if the academic one was a little bumpy. Maia Marie read and commented on drafts in the welcoming space of our writing circle, keeping my creative fires burning during dark times. -

The Premiere Fund Slate for MIFF 2021 Comprises the Following

The MIFF Premiere Fund provides minority co-financing to new Australian quality narrative-drama and documentary feature films that then premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). Seeking out Stories That Need Telling, the the Premiere Fund deepens MIFF’s relationship with filmmaking talent and builds a pipeline of quality Australian content for MIFF. Launched at MIFF 2007, the Premiere Fund has committed to more than 70 projects. Under the charge of MIFF Chair Claire Dobbin, the Premiere Fund Executive Producer is Mark Woods, former CEO of Screen Ireland and Ausfilm and Showtime Australia Head of Content Investment & International Acquisitions. Woods has co-invested in and Executive Produced many quality films, including Rabbit Proof Fence, Japanese Story, Somersault, Breakfast on Pluto, Cannes Palme d’Or winner Wind that Shakes the Barley, and Oscar-winning Six Shooter. ➢ The Premiere Fund slate for MIFF 2021 comprises the following: • ABLAZE: A meditation on family, culture and memory, indigenous Melbourne opera singer Tiriki Onus investigates whether a 70- year old silent film was in fact made by his grandfather – civil rights leader Bill Onus. From director Alex Morgan (Hunt Angels) and producer Tom Zubrycki (Exile in Sarajevo). (Distributor: Umbrella) • ANONYMOUS CLUB: An intimate – often first-person – exploration of the successful, yet shy and introverted, 33-year-old queer Australian musician Courtney Barnett. From producers Pip Campey (Bastardy), Samantha Dinning (No Time For Quiet) & director Danny Cohen. (Dist: Film Art Media) • CHEF ANTONIO’S RECIPES FOR REVOLUTION: Continuing their series of food-related social-issue feature documentaries, director Trevor Graham (Make Hummus Not War) and producer Lisa Wang (Monsieur Mayonnaise) find a very inclusive Italian restaurant/hotel run predominately by young disabled people. -

Visionsplendidfilmfest.Com

Australia’s only outback film festival visionsplendidfilmfest.comFor more information visit visionsplendidfilmfest.com Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival 2017 WELCOME TO OUTBACK HOLLYWOOD Welcome to Winton’s fourth annual Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival. This year we honour and celebrate Women in Film. The program includes the latest in Australian contemporary, award winning, classic and cult films inspired by the Australian outback. I invite you to join me at this very special Australian Film Festival as we experience films under the stars each evening in the Royal Open Air Theatre and by day at the Winton Shire Hall. Festival Patron, Actor, Mr Roy Billing OAM MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND MAJOR EVENTS THE HON KATE JONES MP It is my great pleasure to welcome you to Winton’s Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival, one of Queensland’s many great event experiences here in outback Queensland. Events like the Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival are vital to Queensland’s tourism prosperity, engaging visitors with the locals and the community, and creating memorable experiences. The Palaszczuk Government is proud to support this event through Tourism and Events Queensland’s Destination Events Program, which helps drive visitors to the destination, increase expenditure, support jobs and foster community pride. There is a story to tell in every Queensland event and I hope these stories help inspire you to experience more of what this great State has to offer. Congratulations to the event organisers and all those involved in delivering the outback film festival and I encourage you to take some time to explore the diverse visitor experiences in Outback Queensland. -

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information Updated August 5, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46225 SUMMARY R46225 Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical August 5, 2021 Information Carla Y. Davis-Castro This report provides statistical information on Indigenous peoples in Latin America. Data and Research Librarian findings vary, sometimes greatly, on all topics covered in this report, including populations and languages, socioeconomic data, land and natural resources, human rights and international legal conventions. For example the figure below shows four estimates for the Indigenous population of Latin America ranging from 41.8 million to 53.4 million. The statistics vary depending on the source methodology, changes in national censuses, the number of countries covered, and the years examined. Indigenous Population and Percentage of General Population of Latin America Sources: Graphic created by CRS using the World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab with webpage last updated in July 2021; ECLAC and FILAC’s 2020 Los pueblos indígenas de América Latina - Abya Yala y la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible: tensiones y desafíos desde una perspectiva territorial; the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank’s (WB) 2015 Indigenous Latin America in the twenty-first century: the first decade; and ECLAC’s 2014 Guaranteeing Indigenous people’s rights in Latin America: Progress in the past decade and remaining challenges. Notes: The World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Allison Adelle Hedge Coke Selected Resume Advanced

ALLISON ADELLE HEDGE COKE www.allisonhedgecoke.com www.hedgecoke.com www.rdkla.com www.reddustfilm.com [email protected] [email protected] 405.888.1574 SELECTED RESUME ADVANCED DEGREES/EDUCATION DEGREES IN LITERARY FIELD Vermont College / Norwich University •Postgraduate, Nonfiction/Creative Nonfiction, Merit Scholar, Completed December 1995 •MFAW, Poetry (Fiction), Merit Scholar, (Terminal) MFA Degree July 1995 (Creative and Critical Theses. Critical, a pedagogical paper on teaching creative writing in a cultural setting. Creative, manuscript of original work.) Institute for American Indian Arts •AFAW Creative Writing, Departmental Awards, Naropa Prize, Red Elk Scholarship, Edited two student anthologies: Voices of Thunder and It’s Not Quiet Anymore, (Creative Writing, Sculpture, Native American Studies Courses) Graduated 1993 •Note: Bachelor’s Degree waived upon graduate school acceptance, based upon GRE scores, publications, Professional Performing Arts graduation equivalent, and demonstrated excellence. ADDITIONAL ADVANCED EDUCATION Naropa University •MFA Program Summer Award Fellowships (2), Poetry/Fiction, Naropa Poetry Prize 1992-1993 Fellowship with Allen Ginsberg & Naropa Summer Faculty and Zora Neale Hurston Scholarship Estelle Harmon’s Actors’ Workshop •Professional Performing Arts (Graduated four year professional arts program, BFA equivalent, Performance in Stage, Television, Screen; Script, Directing, Dialects, Period Portrayal, Psychology of the Actor/Character, Camera and Stage Tech) Graduated PPADC 1988 Poverty -

Idolerna Kommer Till Lidköping

Idolerna kommer till Lidköping För varje dag fylls Lidköpings Kultur och Porslinsfestivals program på med roliga, spännande, intressanta, nischade, breda, smala, högljudda och lågmälda akter. Vi har tidigare viskat att State of Drama kommer hit. Den gången vill vi ropa ut att två finfina tjejer som startat sin karriär i TV-programmet Idol också kommer; Linnea Henriksson och Amanda Fondell! Amanda Fondell Amanda Fondell, född 1994 i Kristianstads kommun blev Idol-Amanda med hela svenska folket när hon vann Idol 2011. Amanda Fondell tävlade i finalen mot Sveriges Eurovisionbidragsartist Robin Stjernberg. Amanda Fondell fick 52 % av tv-tittarnas röster och vann därmed 2011 års Idol. Efter finalvinsten släppte Amanda fullängdaren ”All this Way” där singeln med samma namn blev en radiohit i alla kanaler. Nu är Amanda aktuell igen med singeln ”Bastard” som fullkomligt osar av hitpotential. Linnea Henriksson Linnea Henriksson är uppvuxen i Halmstad. För de allra flesta blev hon känd som Idol-Linnea då hon kom 4:a i Idol 2010. Men redan innan Idol hade Linnea en musikkarrär på gång. Då menar vi inte att hon bara 9 år gammal stod på scenen redan 1995 i Småstjärnorna. Nej, 2010 - samma år som Linnea var med i Idol - släpptes hon tillsammans med sitt elektrojazzband PRYLF en platta som fick lysande recensioner. Linnéas solokarriär tog dock fart med Idol och 2011 släppte hon sin första solosingel "Väldigt kär/Obegripligt ensam" som hon skrivit tillsammans med Orup. Den blev den första i en rad av hits som Linnea hittills levererat. Några av de andra är "Lyckligare nu" och "Mitt rum i ditt hjärta".