University of Warwick Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

£389,500 Windwhistle, Church Street, Great Comberton, WR10

Offices throughout Worcestershire & Mayfair, London Windwhistle, Church Street, Great Comberton, WR10 3DS Extended Detached House, Popular Village, Five Bedrooms Allan Morris & Osborne 19 High Street, Pershore, Worcestershire, WR10 1AA £389,500 allan-morris.co.uk allan-morris.co.uk 01386 554747 01386 554747 [email protected] [email protected] Windwhistle, Church Street, Great Comberton, Nr Pershore, Worcestershire, WR10 3DS. Bedroom Four 10’7” x 9’ (3.25m x 2.74m) plus built-in double wardrobe. Radiator and double glazed window to the rear with views across the village towards A Detached House With Five Bedrooms, Situated Within This Sought After Village, Overlooking Fields At The Front The Malverns. And Having First Floor Views To The Rear Across the Village Towards The Malverns. Bedroom Five/Study 12’ x 5’7” (3.65m x 1.72m) The Extended Accommodation Comprises: Reception Hall * Cloakroom * Through Sitting Room * with radiator and double glazed window to the front with views. * Separate Dining Room * L-Shaped Kitchen/Breakfast Room * Utility * Master Bedroom With En-Suite Bathroom * Family Bathroom * Bedroom Two With Shower & Wash Basin * Three Further Bedrooms * Family Bathroom * with a coloured suite comprising panelled bath, WC and wash basin. Radiator and obscure double glazed window to the rear. Airing cupboard with tank and shelves. * Gas Fired Central Heating & Double Glazing * Short Garage * Attractive Gardens * OUTSIDE – Gravelled drive and parking area to the front leading to the garage and area of lawned front garden with LOCATION - Great Comberton lies on the lower slopes of Bredon Hill, a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, flower and shrub borders. -

Warwickshire Industrial Archaeology Society

WARWICKSHIRE IndustrialW ArchaeologyI SociASety NUMBER 31 June 2008 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER THIS ISSUE it was felt would do nothing to web site, and Internet access further these aims and might becoming more commonplace ¢ Meeting Reports detract from them, as if the amongst the Society membership, current four page layout were what might be the feelings of ¢ From The Editor retained, images would reduce the members be towards stopping the space available for text and practice of posting copies to possibly compromise the meeting those unable to collect them? ¢ Bridges Under Threat reports. Does this represent a conflict This does not mean that with the main stated aim of ¢ Meetings Programme images will never appear in the publishing a Newsletter, namely Newsletter. If all goes to plan, that of making all members feel this edition will be something of a included in the activities of the FROM THE EDITOR milestone since it will be the first Society? y editorial in the to contain an illustration; a Mark Abbott March 2008 edition of diagram appending the report of Mthis Newsletter the May meeting. Hopefully, PROGRAMME concerning possible changes to its similar illustrations will be format brought an unexpected possible in future editions, where Programme. number of offers of practical appropriate and available, as the The programme through to help. These included the offer of technology required to reproduce December 2008 is as follows: a second hand A3 laser printer at them is now quite September 11th a very attractive price; so straightforward. The inclusion of Mr. Lawrence Ince: attractive as to be almost too photographs is not entirely ruled Engine-Building at Boulton and good an opportunity to ignore. -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 14/06/2021 to 18/06/2021 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 21/00759/HP Location: Meadway House, 11 High Street, Badsey, Evesham, WR11 7EW Proposal: Replacement garden building in rear garden Decision Date: 18/06/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Ms Lucy Close Agent: Scott Associates LLP Meadway House 1 Watton Road 11, High Street Knebworth Badsey SG3 6AH WR11 7EW Parish: Badsey Ward: Badsey Ward Case Officer: Robert Smith Expiry Date: 18/06/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862410 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 21/00760/LB Location: Meadway House, 11 High Street, Badsey, Evesham, WR11 7EW Proposal: Replacement garden building in rear garden Decision Date: 18/06/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Ms Lucy Close Agent: Scott Associates LLP Meadway House 1 Watton Road 11, High Street Knebworth Badsey SG3 6AH WR11 7EW Parish: Badsey Ward: Badsey Ward Case Officer: Robert Smith Expiry Date: 18/06/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862410 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 24 Application No: 20/02763/FUL Location: Public Conveniences, Waterside, Evesham, WR11 1BS Proposal: Demolition of public toilets to basement level and rebuilding including alterations to steps, tree works and landscaping. Decision Date: 15/06/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Wychavon District Council Agent: Jason Yarwood Civic Centre The Council House Queen Elizabeth Drive Avenue Road Pershore Malvern WR10 1PT WR143AF Parish: Evesham Ward: Bengeworth Ward Case Officer: Gillian McDermott Expiry Date: 12/03/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862445 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 21/00159/FUL Location: Land Adjacent To Abbey Park, Abbey Road, Evesham Proposal: Removal of parlous fabric at the east end of the historic nave. -

Of the Journal of the Historical Metallurgy Society

Index of the Journal of the Historical Metallurgy Society Volume 1 No. 1 Table of 17th and 18th Century Blast Furnaces Volume 1 No. 2 Table of 17th and 18th Century Ironworks Some Details of an Early Furnace (Cannock Chase) Morton, G.R. Volume 1 No. 3 Coed Ithel Blast Furnace Melbourne Blast Furnace Maryport Blast Furnace Bloomeries Volume 1 No. 4 Blast Furnaces and the 17th and 18th Century Survey Eglwysfach Furnace Drawing Supplement – Little Aston Forge cAD1574 to AD1798 Morton, G.R. & Gould, J. Volume 1 No. 5 17th and 18th Century Blast Furnaces Bloomeries and Forges Exeter Excavations Remains of Cornish Tin and Copper Smelting Metallographic Examination of Middle and Late Bronze Age artefacts Burgess, C. & Tylecote, R. Table of Furnaces Volume 1 No. 6 The Iron Industry in the Roman Period Cleere & Bridgewater Yarranton’s Blast Furnace at Sharpley Pool, Worcestershire Hallett, M. and Morton, G. Charlcote Furnace, 1733 to 1779 Mutton, N. The Early Coke Era Morton, G.R. The Bradley Ironworks of John Wilkinson Smith, W.E. Volume 1 No. 7 Copper Smelting Experiments Anstee, J.W. Notes Concerning Copper Smelting Lorenzen, W. Analysis of Trojan Bronzes Tylecote, R.F. and E. Investigation of an Iron Object from Lower Slaughter O’Neil, H.E. Volume 1 No. 8 Lead Smelting in Derbyshire Mott, R.A. The Bloomery at Rockley Smithies, Yorkshire Crossley, D.W. Abbeydale Works, Sheffield Bestall, J. The Cementation and Crucible Steel Processes Barraclough, K.C. Volume 1 No. 9 The Composition of 35 Roman Bronze Coins of the Period AD284 to 363 Cope, L. -

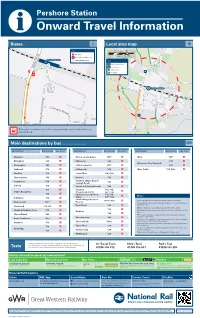

Pershore Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Pershore Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Key km 0 0.5 A Bus Stop 0 Miles 0.25 Rail replacement Bus Stop Pershore Station Station Entrance/Exit Key 10 PH Pershore High School m in u te S Local Shop s Station Road w e a Driv l ion Cycle routes k tat in S g B S d A Footpaths is t a n c e rive ion D Pershore Station Stat e e c c n n a a t t s s i i d d g g n n i i k k l l a a w w s s e e t t u u n n i i m m 0 0 1 1 PH Rail replacement buses/coaches depart from the top of station drive on To Pershore Station Road. Town Centre Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Abberton 564 B Hinton-on-the-Green 565* A Wick 565* A Birlingham 53# A Inkberrow 564 B 51# A Worcester (City Centre) ^ Bishampton 564 B Little Comberton 565* A 53# B Caldewell 51# A Littleworth 53# B Wyre Piddle 51#, 564+ B Charlton 51# B Lower Moor 51#, 564+ B Church Lench 564 B Norton 53# B Pershore (Abbey Estate/ Cropthorne 51# B 566 A Farleigh Road) Defford 53# A Pershore (Cherry Orchard) 566 A 51# A Pershore 51#, 53#, A Drakes Broughton (Town Centre) 565*, 566 53# B Pinvin Crossroads (Post 51#, 53#, B Notes Eckington 53# A Office) 565*, 566 Pinvin Village (Coach & 564++, 566 B Bus routes 564, 565 and 566 operate Mondays to Saturdays. -

Edward III, Vol. 13, P

H! 368 CALENDAR OF PATENT BOLLS. 1366. Membrane \2£—cont. at Sheffeld, co. York, and Wirksop, co. Nottingham, and entered his free chace at Sheffeld, Ecclesfeld, Bradefeld and Handesworth and his free warren at the same places and Wirksop, hunted in these, carried away goods at Sheffeld, deer from the parks and chaces, and hares, conies, pheasants and partridges from the warrens, and assaulted his men and servantsi . For 20s. paid in the hanaper. Nov. 8. Commission of oyer and terminer to John Butetourt, John Knyvet, Westminster. William de Shareshull, Thomas de Ingelby, Robert de Bracy and Thomas de Stok, on complaint by Thomas de Bello Campo, earl of Warwick, that some evildoers at divers times broke his parks at Wadbergh, Sallewarp, Elmell Lovet, Chaddesle, Abbedeleye, , Cynteleye and Boelegh, entered his free warrens at Elmell Castell, I Netherton, Great Comberton, Little Comberton, Overbury, Wolashull, ' Depford, Croppethorn, Wyke by Pershore, Simondescrombe and Shirreveslench, co. Worcester, hunted in these, fished in his stews, at Elmell Castell, Sallewarp, Piryton, Poer, Boelegh and Haddesore, and carried away fish therefrom, deer from the parks, and hares, conies, pheasants and partridges from the warrens. By K. MEMBRANE Nov. 20. Commission of oyer and terminer to Thomas de Ingelby, William de Westminster. Ferrariis, Ralph Basset of Sapcote, Roger de Belers, Simon Pakeman, Richard de Gaddesby and Laurence Hauberk of Claxton, touching those who killed John atte Brok at Foxton, co. Leicester, and broke the close and houses of Richard de Foxton there and carried away his goods. • ByC. Nov. 26. Commission to Ralph Spigurnell, constable of the castle of Dover, or Westminster, his lieutenants, and to John Edward, Henry Pryme, William Swetman i and John Wantenge, to arrest and bring before the council brother ii William de Eltonheved to answer touching many frauds and misdeeds w perpetrated by him against the king'^ majesty. -

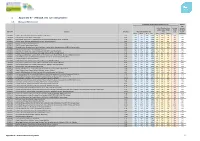

JBA Consulting Report Template 2015

1 Appendix B – SHELAA site screening tables 1.1 Malvern Hills District Proportion of site shown to be at risk (%) Area of site Risk of flooding from Historic outside surface water (Total flood of Flood Site code Location Area (ha) Flood Zones (Total %s) %s) map Zones FZ 3b FZ 3a FZ 2 FZ 1 30yr 100yr 1,000yr (hectares) CFS0006 Land to the south of dwelling at 155 Wells road Malvern 0.21 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 6% 0% 0.21 CFS0009 Land off A4103 Leigh Sinton Leigh Sinton 8.64 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% <1% 4% 0% 8.64 CFS0011 The Arceage, View Farm, 11 Malvern Road, Powick, Worcestershire, WR22 4SF Powick 1.79 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.79 CFS0012 Land off Upper Welland Road and Assarts Lane, Malvern Malvern 1.63 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.63 CFS0016 Watery Lane Upper Welland Welland 0.68 0% 0% 0% 100% 4% 8% 26% 0% 0.68 CFS0017 SO8242 Hanley Castle Hanley Castle 0.95 0% 0% 0% 100% 2% 2% 13% 0% 0.95 CFS0029 Midlands Farm, (Meadow Farm Park) Hook Bank, Hanley Castle, Worcestershire, WR8 0AZ Hanley Castle 1.40 0% 0% 0% 100% 1% 2% 16% 0% 1.40 CFS0042 Hope Lane, Clifton upon Teme Clifton upon Teme 3.09 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 3.09 CFS0045 Glen Rise, 32 Hallow Lane, Lower Broadheath WR2 6QL Lower Broadheath 0.53 0% 0% 0% 100% <1% <1% 1% 0% 0.53 CFS0052 Land to the south west of Elmhurst Farm, Leigh Sinton, WR13 5EA Leigh Sinton 4.39 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 4.39 CFS0060 Land Registry. -

"'"ORCESTERSHIRE. [KELLY's

328 FAR "'"ORCESTERSHIRE. [KELLY's FARMERS-continued. Byng Mrs. Thomas, Eachway, Lickoy, Clemens G.Broughton Hackett,Worcst1 Brick James, Broadway Bromsgrove Cleveley John, Stock, Redditch Bridge David, Dore Houre fields, Hun- Byrd Corneliul'l, Hampton, Evesham *Clews John, Gannow green, Halesowen nington, Birmingham Byrd Henry, Hampton, Evesham Clift Wm. Robt. Hardwick,Tewkesbury Bridges Edmnnd, Welland, Gt. Malvern Byrd Mrs.Theodosia,Bretforton,Eveshm Clifton Edmund, Banley Child, 'fenbury Brierley J. Cook hill, Inkberrow, Alcester Cadle Robert, Bickley, Knighton·on- Clinton 'l'hos. Welland, Great Malvern BriggsT.ChaddesleyCorbett,Kiddrmnstr Teme, Tenbury Clutterbuck John, The Retreat, Castle Bright John, Sytchampton, Stourport 1·Caldecott Nathaniel, Pigeon house, Morton, Tewkesbury Briney Geo. Ab!Jott's Morton, Redditch Kyre Wyard, Ten bury Clutterbuck Shadner,Staunton,Gioucstr BroadE.O.Tapenhall,Selwarpe,Droitwch Camden Jsph.AstonMagna, BlockleyS.O Cocks John, Drakes cross, Redditch Broadhurst James Henry, I"ower Moor Candy J.<'redk.Chas. Kinsham,Tewkesbry Cole Misses, Hanley castle, Worcester end, Mamble, Bewdley tCandy Thomas, Kyrewood, Ten bury Cole George, Dodford lodge,llromsgrore Broadway Daniel, .Far Forest, Bewdley Careless J.C.Great Comberton,Pershore Cole James Stanton, Wo01mere cottage, Broadway Thomas, Cook's green, Far Careless Mrs. l\LSth Littleton,Evesham Hanbury, Bromsgrove Forest, Bewdley Careless Richard, Offenham, Evesham Cole Nehemiah, Elmley ca~tle, Pcrshore Brooke G. Severn Stoke, Worcester CarelessRichard,Priory piece,Inkberrow, Cole Nehemiah, Sedgeberrow, Evesham · Brookes Noahdia, Lumber tree, Welland, Redditeh Cole Wm. Henry, Ct·op1.]10rne, Pershore Great Malvern Careless Samuel, Inkberrow. Redditch Coles Thomas, Wolverley, Kidderminstr Brool,esS.Kingsford, Wolverley,Klltnnstr Careless Thos. North Littleton,Evesham Coley Edwd. Gannow green, Halesowen Brooks Charles, Abberton, Pershore Careless Wm. -

Industrial Biography

Industrial Biography Samuel Smiles Industrial Biography Table of Contents Industrial Biography.................................................................................................................................................1 Samuel Smiles................................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. IRON AND CIVILIZATION..................................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. EARLY ENGLISH IRON MANUFACTURE....................................................................16 CHAPTER III. IRON−SMELTING BY PIT−COAL−−DUD DUDLEY...................................................24 CHAPTER IV. ANDREW YARRANTON.................................................................................................33 CHAPTER V. COALBROOKDALE IRON WORKS−−THE DARBYS AND REYNOLDSES..............42 CHAPTER VI. INVENTION OF CAST STEEL−−BENJAMIN HUNTSMAN........................................53 CHAPTER VII. THE INVENTIONS OF HENRY CORT.........................................................................60 CHAPTER VIII. THE SCOTCH IRON MANUFACTURE − Dr. ROEBUCK DAVID MUSHET..........69 CHAPTER IX. INVENTION OF THE HOT BLAST−−JAMES BEAUMONT NEILSON......................76 CHAPTER X. MECHANICAL INVENTIONS AND INVENTORS........................................................82 -

Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area 1 Contents 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area .............................................................. 3 2. Table of Resources ........................................................................................................................ 4 3. 'See Under' List ............................................................................................................................. 23 4. Glossary of Terms ........................................................................................................................ 33 2 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area The following is a guide to the types of records we hold and the areas we may cover within the Self Service Area of the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service. The Self Service Area has the same opening hours as the Hive: 8.30am to 10pm 7 days a week. You are welcome to browse and use these resources during these times, and an additional guide called 'Guide to the Self Service Archive Area' has been developed to help. This is available in the area or on our website free of charge, but if you would like to purchase your own copy of our guides please speak to a member of staff or see our website for our current contact details. If you feel you would like support to use the area you can book on to one of our workshops 'First Steps in Family History' or 'First Steps in Local History'. For more information on these sessions, and others that we hold, please pick up a leaflet or see our Events Guide at www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas. About the Guide This guide is aimed as a very general overview and is not intended to be an exhaustive list of resources.