Croatia Country Report BTI 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

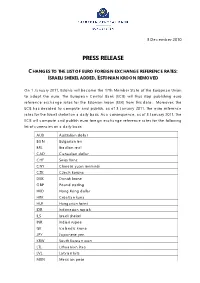

Press Release Changes to the List of Euro Foreign Exchange Reference

3 December 2010 PRESS RELEASE CHANGES TO THE LIST OF EURO FOREIGN EXCHANGE REFERENCE RATES: ISRAELI SHEKEL ADDED, ESTONIAN KROON REMOVED On 1 January 2011, Estonia will become the 17th Member State of the European Union to adopt the euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) will thus stop publishing euro reference exchange rates for the Estonian kroon (EEK) from this date. Moreover, the ECB has decided to compute and publish, as of 3 January 2011, the euro reference rates for the Israeli shekel on a daily basis. As a consequence, as of 3 January 2011, the ECB will compute and publish euro foreign exchange reference rates for the following list of currencies on a daily basis: AUD Australian dollar BGN Bulgarian lev BRL Brazilian real CAD Canadian dollar CHF Swiss franc CNY Chinese yuan renminbi CZK Czech koruna DKK Danish krone GBP Pound sterling HKD Hong Kong dollar HRK Croatian kuna HUF Hungarian forint IDR Indonesian rupiah ILS Israeli shekel INR Indian rupee ISK Icelandic krona JPY Japanese yen KRW South Korean won LTL Lithuanian litas LVL Latvian lats MXN Mexican peso 2 MYR Malaysian ringgit NOK Norwegian krone NZD New Zealand dollar PHP Philippine peso PLN Polish zloty RON New Romanian leu RUB Russian rouble SEK Swedish krona SGD Singapore dollar THB Thai baht TRY New Turkish lira USD US dollar ZAR South African rand The current procedure for the computation and publication of the foreign exchange reference rates will also apply to the currency that is to be added to the list: The reference rates are based on the daily concertation procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks, which normally takes place at 2.15 p.m. -

News in Brief 12 July

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe OSCE Mission to Croatia News in brief 12 July – 25 July 2006 Prime Minister Sanader visits Serbia On 21 July, Croatian Prime Minister Ivo Sanader paid his second official visit to Serbia, further intensifying bilateral relations between the two countries. Prime Minister Sanader made his first visit to Belgrade in November 2004, followed by a reciprocal visit to Zagreb by Serbian Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica in November 2005. Prior to their meeting in Belgrade the two Prime Ministers officially opened the newly renovated border crossing between Croatia and Serbia in Bajakovo, Eastern Croatia. At the ceremony attended by representatives of both governments and the diplomatic corps from Zagreb and Belgrade, the Croatian Premier said that "today we are opening the future of new relations between our two countries." Echoing this sentiment, Prime Minister Koštunica added that both the "Serbian and Croatian governments will work to heal wounds from the past and build a new future for the two states in a united Europe". Later, following talks in Belgrade, both Prime Ministers declared that Serbia and Croatia have a joint objective, to join the European Union, and that strong bilateral relations between the two countries should be the foundation of political security in the region. Prime Minister Sanader commended the efforts both governments had made towards improving the position of minorities in line with the bilateral agreement on minority protection signed between the two countries in November 2004. He went on to stress his cabinet’s wish to see the Serb minority fully integrated into Croatian society. -

Exchange Market Pressure on the Croatian Kuna

EXCHANGE MARKET PRESSURE ON THE CROATIAN KUNA Srđan Tatomir* Professional article** Institute of Public Finance, Zagreb and UDC 336.748(497.5) University of Amsterdam JEL F31 Abstract Currency crises exert strong pressure on currencies often causing costly economic adjustment. A measure of exchange market pressure (EMP) gauges the severity of such tensions. Measuring EMP is important for monetary authorities that manage exchange rates. It is also relevant in academic research that studies currency crises. A precise EMP measure is therefore important and this paper re-examines the measurement of EMP on the Croatian kuna. It improves it by considering intervention data and thresholds that ac- count for the EMP distribution. It also tests the robustness of weights. A discussion of the results demonstrates a modest improvement over the previous measure and concludes that the new EMP on the Croatian kuna should be used in future research. Key words: exchange market pressure, currency crisis, Croatia 1 Introduction In an era of increasing globalization and economic interdependence, fixed and pegged exchange rate regimes are ever more exposed to the danger of currency crises. Integrated financial markets have enabled speculators to execute attacks more swiftly and deliver devastating blows to individual economies. They occur when there is an abnormally large international excess supply of a currency which forces monetary authorities to take strong counter-measures (Weymark, 1998). The EMS crisis of 1992/93 and the Asian crisis of 1997/98 are prominent historical examples. Recently, though, the financial crisis has led to severe pressure on the Hungarian forint and the Icelandic kronor, demonstrating how pressure in the foreign exchange market may cause costly economic adjustment. -

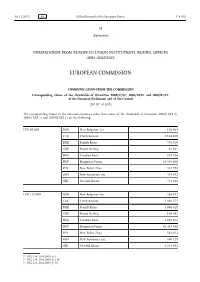

Corresponding Values of the Thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC, 2004/18/EC and 2009/81/EC, of the European Parliament and of the Council (2015/C 418/01)

16.12.2015 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 418/1 II (Information) INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION Corresponding values of the thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC, 2004/18/EC and 2009/81/EC, of the European Parliament and of the Council (2015/C 418/01) The corresponding values in the national currencies other than euros of the thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC (1), 2004/18/EC (2) and 2009/81/EC (3) are the following: EUR 80 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 156 464 CZK Czech Koruna 2 184 400 DKK Danish Krone 596 520 GBP Pound Sterling 62 842 HRK Croatian Kuna 610 024 HUF Hungarian Forint 24 549 600 PLN New Polish Zloty 333 992 RON New Romanian Leu 355 632 SEK Swedish Krona 731 224 EUR 135 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 264 033 CZK Czech Koruna 3 686 175 DKK Danish Krone 1 006 628 GBP Pound Sterling 106 047 HRK Croatian Kuna 1 029 416 HUF Hungarian Forint 41 427 450 PLN New Polish Zloty 563 612 RON New Romanian Leu 600 129 SEK Swedish Krona 1 233 941 (1) OJ L 134, 30.4.2004, p. 1. (2) OJ L 134, 30.4.2004, p. 114. (3) OJ L 216, 20.8.2009, p. 76. C 418/2 EN Official Journal of the European Union 16.12.2015 EUR 209 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 408 762 CZK Czech Koruna 5 706 745 DKK Danish Krone 1 558 409 GBP Pound Sterling 164 176 HRK Croatian Kuna 1 593 688 HUF Hungarian Forint 64 135 830 PLN New Polish Zloty 872 554 RON New Romanian Leu 929 089 SEK Swedish Krona 1 910 323 EUR 418 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 817 524 CZK Czech Koruna 11 413 790 DKK -

Croatia: Three Elections and a Funeral

Conflict Studies Research Centre G83 REPUBLIC OF CROATIA Three Elections and a Funeral The Dawn of Democracy at the Millennial Turn? Dr Trevor Waters Introduction 2 President Tudjman Laid To Rest 2 Parliamentary Elections 2/3 January 2000 5 • Background & Legislative Framework • Political Parties & the Political Climate • Media, Campaign, Public Opinion Polls and NGOs • Parliamentary Election Results & International Reaction Presidential Elections - 24 January & 7 February 2000 12 Post Tudjman Croatia - A New Course 15 Annex A: House of Representatives Election Results October 1995 Annex B: House of Counties Election Results April 1997 Annex C: Presidential Election Results June 1997 Annex D: House of Representatives Election Results January 2000 Annex E: Presidential Election Results January/February 2000 1 G83 REPUBLIC OF CROATIA Three Elections and a Funeral The Dawn of Democracy at the Millennial Turn? Dr Trevor Waters Introduction Croatia's passage into the new millennium was marked by the death, on 10 December 1999, of the self-proclaimed "Father of the Nation", President Dr Franjo Tudjman; by make or break Parliamentary Elections, held on 3 January 2000, which secured the crushing defeat of the former president's ruling Croatian Democratic Union, yielded victory for an alliance of the six mainstream opposition parties, and ushered in a new coalition government strong enough to implement far-reaching reform; and by two rounds, on 24 January and 7 February, of Presidential Elections which resulted in a surprising and spectacular victory for the charismatic Stipe Mesić, Yugoslavia's last president, nonetheless considered by many Croats at the start of the campaign as an outsider, a man from the past. -

RELIGION and YOUTH in CROATIA Dinka Marinović Jerolimov And

RELIGION AND YOUTH IN CROATIA Dinka Marinović Jerolimov and Boris Jokić Social and Religious Context of Youth Religiosity in Croatia During transitional periods, the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe shared several common characteristics regarding religious change. These can be roughly summarized as the influence of religion during the collapse of the communist societal system; the revitalization of religion and religiosity; a national/religious revival; an increase in the number of new religious movements; the politiciza- tion of religion and “religionization” of politics; and the as pirations of churches to regain positions they held in the pre-Communist period (Borowik, 1997, 1999; Hornsby-Smith, 1997; Robertson, 1989; Michel, 1999; Vrcan, 1999). In new social and political circumstances, the posi- tion of religion, churches, and religious people significantly changed as these institutions became increasingly present in public life and the media, as well as in the educational system. After a long period of being suppressed to the private sphere, they finally became publicly “visible”. The attitude of political structures, and society as a whole, towards religion and Churches was clearly reflected in institutional and legal arrangements and was thus reflected in the changed social position of religious communities. These phenomena, processes and tendencies can be recognized as elements of religious change in Croatia as well. This particularly refers to the dominant Catholic Church, whose public role and impor- tance -

From Understanding to Cooperation Promoting Interfaith Encounters to Meet Global Challenges

20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS FROM UNDERSTANDING TO COOPERATION PROMOTING INTERFAITH ENCOUNTERS TO MEET GLOBAL CHALLENGES Zagreb, 7 - 8 December 2017 20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS / 3 PROGRAMME 10:00-12:30 hrs / Sessions I and II The role of religion in European integration process: expectations, potentials, limits Wednesday, 6 December 10:00-11:15 hrs Session I 20.30 hrs. / Welcome Reception hosted by the Croatian Delegation / Memories and lessons learned during 20 years of Dialogue Thursday, 7 December Co-Chairs: György Hölvényi MEP and Jan Olbrycht MEP, Co-Chairmen of 09:00 hrs / Opening the Working Group on Intercultural Activities and Religious Dialogue György Hölvényi MEP and Jan Olbrycht MEP, Co-Chairmen of the Working Opening message: Group on Intercultural Activities and Religious Dialogue Dubravka Šuica MEP, Head of Croatian Delegation of the EPP Group Alojz Peterle MEP, former Responsible of the Interreligious Dialogue Welcome messages Interventions - Mairead McGuinness, First Vice-President of the European Parliament, - Gordan Jandroković, Speaker of the Croatian Parliament responsible for dialogue with religions (video message) - Joseph Daul, President of the European People’ s Party - Joseph Daul, President of the European People’ s Party - Vito Bonsignore, former Vice-Chairman of the EPP Group responsible for - Andrej Plenković, Prime Minister of Croatia Dialogue with Islam - Mons. Prof. Tadeusz Pieronek, Chairman of the International Krakow Church Conference Organizing Committee - Stephen Biller, former EPP Group Adviser responsible for Interreligious Dialogue Discussion 20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS / 5 4 /20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS 11:15-12:30 hrs. -

Freedom House, Its Academic Advisers, and the Author(S) of This Report

Croatia by Tena Prelec Capital: Zagreb Population: 4.17 million GNI/capita, PPP: $22,880 Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores NIT Edition 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 National Democratic 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.75 Governance Electoral Process 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3 3 3 Civil Society 2.75 2.75 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 Independent Media 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4.25 4.25 Local Democratic 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 Governance Judicial Framework 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.5 4.5 4.5 4.5 4.5 and Independence Corruption 4.5 4.5 4.25 4 4 4 4 4.25 4.25 4.25 Democracy Score 3.71 3.71 3,64 3.61 3.61 3.68 3.68 3.68 3.71 3.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. -

Barbara Peranic

Reuters Fellowship Paper, Oxford University ACCOUNTABILITY AND THE CROATIAN MEDIA IN THE PROCESS OF RECONCILIATION Two Case Studies By Barbara Peranic Michaelmas 2006/Hilary 2007 CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Section 1………………………………………………………………………………………4 Introduction……….…………………………………………………............................4 The Legacy of the Past.………………………………………………………………...5 Section 2………………………………………………………………………..........................7 Regulations & Mechanisms to Prevent Hate Speech ………………………………… 7 Croatian Journalists’ Association……………………………………………………....9 Vecernji list’s Ombudsman and Code of Practice…………………………………...10 Letters to the Editor/Comments………………………………………………………12 Media Watchdogs …………………………………………………….........................12 Section 3………………………………………………………………………........................13 Selected Events and Press Coverage………………………………….........................13 Biljani Donji …………………………………………………….................................13 Donji Lapac …………………………………………………………………………..21 Section 4………………………………………………………………………………………29 The Question of Ethics………………………………………………..........................29 Section 5…………………………………………………………………………....................32 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….32 2 Acknowledgements I want to express my gratitude to the Reuters Institute for giving me the opportunity to conduct this research. My warm thanks to all of the Reuters Institute team who gave so freely of their time and especially to Paddy Coulter for being an inspiring director and a wonderful host. I owe a huge dept of -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Religious Freedom in Croatia: the Current State and Perspectives

Centrum Analiz Strategicznych Instytutu Wymiaru Sprawiedliwości For the freedom to profess religion in the contemporary world. Counteracting the causes of discrimination and helping the persecuted based on the example of Christians Saša Horvat The religious freedom in Croatia: the current state and perspectives [Work for the Institute of Justice] Warsaw 2019 The Project is co-financed by the Justice Fund whose administrator is the Minister of Justice Content Introduction / 3 1. Definitions of religious persecution and freedom to profess religion / 4 1.1. The rologueP for freedom to profess religion / 4 1.1.1. Philosophical and theological perspectives of the concept of freedom / 4 1.1.2. The concept of religion / 5 1.1.3. The freedom to profess religion / 7 1.2. The freedom to profess religion – legislative framework / 7 1.2.1. European laws protecting the freedom to profess religion / 7 1.2.2. Croatian laws protecting the freedom to profess religion / 8 1.3. Definitions of religious persecution and intolerance toward the freedom to profess religion / 9 1.3.1. The religious persecution / 9 1.3.1.1. Terminological clarifications / 10 2. The freedom to profess religion and religious persecution / 10 2.1. The situation in Europe / 10 2.2. The eligiousr persecution in Croatia / 13 3. The examples of religious persecutions in Croatia or denial of religious freedom / 16 3.1. Religion persecution by the clearing of the public space / 16 3.2. Religion symbols in public and state institutions / 19 3.3. Freedom to profess religious teachings and attitudes / 22 3.3.1. Freedom to profess religious teachings and attitudes in schools / 22 3.3.2. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Welcome to the Desert of Transition! Citation for published version: Stiks, I & Horvat, S 2012, 'Welcome to the Desert of Transition! Post-socialism, the European Union and a New Left in the Balkans', Monthly Review, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 38-48. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Monthly Review Publisher Rights Statement: © Stiks, I., & Horvat, S. (2012). Welcome to the Desert of Transition! Post-socialism, the European Union and a New Left in the Balkans. Monthly Review, 63(10), 38-48 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Welcome to the Desert of Transition! Post-socialism, the European Union and a New Left in the Balkans Srećko Horvat and Igor Štiks1 In the shadow of the current political transformations of the Middle East, a wave of protest from Tel Aviv, Madrid to Wall Street, and the ongoing Greek crisis, the post- socialist Balkans has been boiling.