Engendering Climate Change; Learnings from South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2015

VOL 11 | No. 05 Aug, Sep -Oct, 2015 from the desk of the PRESIDENT Dear Member, 9th October, 2015 Our heartiest greetings to you and your family and for everyone in Bengal for the upcoming seasons! This is my first message to you after having been elected President PT, Entertainment Tax, and Entry Tax. It is one of the only 3 States of this august and historic institution, and I am delighted to share to issue a single Tax ID to cover all State taxes. Additionally, the with you that your Chamber has embraced the new year with great State has exempted 49 industries/activities from pollution control verve. Plans for the year are already being implemented, and each board clearances as a prerequisite to start business. They have also week is witnessing several programmes and activities, which are come up with a single window (Shilpa Sathi) system for large being undertaken almost simultaneously. industries and MSME Facilitation Centre (MFC) for MSMEs. This year the survey was based on 98 points, next year the benchmark We have embarked on new ventures focused on capital formation would be raised by introducing a 330-point action plan on which the together with inclusive growth and have pledged to work with the states have to work. We offer our wholehearted support to the State Government of West Bengal in the latter’s endeavour to bring about Government to address these issues, to trigger a participatory and inclusive growth along with a pro-business environment. In this knowledge-driven reform process and bring West Bengal up to the endeavour, we are meeting with the Government at various levels top 3 States in the next year's survey. -

GA-10.03 CHITTOOR, KOLAR and VELLORE DISTRICTS.Pdf

77°50'0"E 78°0'0"E 78°10'0"E 78°20'0"E 78°30'0"E 78°40'0"E 78°50'0"E 79°0'0"E 79°10'0"E 79°20'0"E 79°30'0"E 79°40'0"E 79°50'0"E 80°0'0"E GEOGRAPHICAL AREA CHITTOOR, KOLAR AND N N " " VELLORE DISTRICTS 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 4 ± 4 1 1 Peddamandyam ! CA-03 CA-05 KEY MAP PEDDAMANDYAM MULAKALACHERUVU ! Kalicherla N CA-52 N " CA-11 " 0 Sompalle CA-04 CA-06 CA-60 0 ' ! SRIKALAHASTI ' 0 Veligallu KAMBHAMVARIPALLE 0 5 THAMBALLAPA! LLI ! GURRAMKONDA ! THOTTAMBEDU 5 ° ° 3 Thamballapalle Kalakada Kambhamvaripalle CA-21 3 1 Mulakalacheruvu 1 ! ! Á! CA-10 YERRAVARIPALEM 565 ANDHRA Gurramkonda ! ¤£ CA-02 ! Pedda Kannali PRADESH Kosuvaripalle KALAKADA CA-20 Bodevandlapalle Á! ! PEDDATHIPPASAMUDRAM ! Gundloor PILERU KARNATAKA ! CA-51 CA-53 (! Á! CA-40 Á! Á! Pattamvandlapalle Burakayalakota RENIGUNTA Srikalahasti ! ! TIRUPATI Á! YERPEDU Peddathippasamudram Rangasamudram ! ! ! Maddin!ayanipalCle H MudIivedu T T O O R CA-22 URBAN Á! Á ! ¤£31 CA-12 ! Karakambadi (Rural) ! ROMPICHERLA Á ! ! N Á N " Thummarakunta CA-07 KALIKIRI (! Tirumala CA-61 " 0 0 ' ! ' CA-09 Rompicherla ! Á 0 B.Kothakota KURÁ!ABALAKOTA ! Mangalam 0 4 ! CA-01 Á Chinnagotti Gallu ! BN 4 ° 71 ( ° ! VALMIKIPURAM Kalikiri ¤£ (! ! CA-39 3 Pileru 3 ! ! ! Renigunta 1 B Kurabalakota Á! ! KHANDRIGA 1 Thettu ! Á Akkarampalle (! TA M I L N A D U ChinnathippasamudÁ!ram Á!Chintaparthi CHINNAGOTTIGALLU (! ! Á! KOTHAKOTA ! ! Á! Kalikirireddivari Palle ! Doddipalle ! Á! Á Vikruthamala Badikayalapalle ! Angallu ! (! Á ! Kothavaripalle Á! CA-4(!1 ! Valmikipuram Á! Cherlopalle (! Varadaiahpalem Gattu ! ! ! Daminedu -

A Study on Characterization & Treatment of Laundry Effluent

IJIRST –International Journal for Innovative Research in Science & Technology| Volume 4 | Issue 1 | June 2017 ISSN (online): 2349-6010 A Study on Characterization & Treatment of Laundry Effluent Prof Dr K N Sheth Mittal Patel Director Assistant Professor Geetanjali Institute of Technical Studies, Udaipur SVBIT, Gandhi Nagar (Gujarat) Mrunali D Desai Assistant Professor Department of Environmental Engineering ISTAR, Vallabh Vdyanagar (Gujarat) Abstract It is a substantial fact that specific disposal standard for laundry effluent have not been prescribed by Gujarat pollution Control Board (GPCB). Laundry waste uses soap, soda, detergents and other chemicals for removal of stains, oil, grease and dirt from the soil clothing. The laundry waste is originated in the residential zone on account of manual cleaning, cleaning by domestic washing machines as well as large amount of effluents are generated by commercial washing including dry-cleaning. An attempt has been made in the present investigation to generalize the characteristics of laundry effluent generated by various sources in Vadodara (Gujarat). It has been found during the laboratory studies, that SS, BOD and COD of laundry waste are high. Treatability studies were carried out in the environmental engineering laboratory of B.V.M. Engineering College, V.V.Nagar for removal of these contaminants. The coagulation-flocculation followed by dual media filtration was found to be most suitable sequence of the treatment. Keywords: Laundry effluent, soil clothing, coagulation-flocculation, dual media filtration _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ I. INTRODUCTION Laundry industry is a service industry, In other words, laundry industry is not a manufacturing industry. [1] The State Pollution Control Board has, therefore, not framed standards for specific contaminant levels for the disposal of Laundry waste. -

Nov 2012 Nmms Examination Selected Provisional List ( Bangalore North )

NOV 2012 NMMS EXAMINATION SELECTED PROVISIONAL LIST ( BANGALORE NORTH ) SL No ROLL NUMBER CANDIDATE NAME FATHER NAME CAT SCHOOL ADDRESS MAT SAT TOTAL RANK GM 1 241120106407 AASHIQ IBRAHIM K KHAJA MOHIDEEN 6 VKN HIGH SCHOOL 101-103 VI CROSS KP WEST 57 59 116 1 2 241120106082 DEONA MERIL PINTO DANIEL O PINTO 1 STELLA MARIS HIGH SCHOOL #23 GD PARK EXTN 57 57 114 2 3 241120111001 AARTHI A ASHOK KUMAR R 1 ST CHARLES HIGH SCHOOL ST THOMAS TOWM 59 54 113 3 4 241120111062 NAGARAJ N NEELAKANDAN K 1 ST JOSEPH INDIAN HIGH SCHOOL 23 VITTAL MALLYA ROAD 55 58 113 3 5 241120116107 MANOJ M 1 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE YELAHANKA 59 52 111 4 6 241120106316 SHIVANI KINI DEVANANDHA KINI 1 STELLA MARIS HIGH SCHOOL #23 GD PARK EXTN VYALIKAVAL 55 54 109 5 7 241120106307 SHASHANK N NARAYANASWAMY H 2 BEL HIGH SCHOOL JALAHALLI 56 52 108 6 8 241120106254 R PRATHIBHA D RAMACHANDRA 1 NIRMALA RANI HIGH SCHOOL MALLESHWARAM 18TH CROSS 46 58 104 7 9 241120106378 VARSHA R V RAMCHAND H V 1 STELLA MARIS HIGH SCHOOL 23GD PARK EXTN 65 39 104 7 10 241120106398 YASHASVI V AIGAL VENKATRAMANA AIGAL 1 BEL HIGH SCHOOL JALAHALLI POST 48 55 103 8 11 241120116013 AMRUTHA GB BABU 5 GOVT PU COLLEGE HIGH SCHOOL DIVIJAKKURU YALAHANKA PO 52 51 103 8 12 241120111048 S LAVANYA D SUNDAR 1 INDIRANAGAR HIGH SCHOOL 5TH MAIN 9TH CROSS INDIRANAGAR 51 48 99 9 13 241120111046 T KIRAN KUMAR TS THIPPE SWAMY 5 ST JOSEPH INDIAN HIGH SCHOOL VITTAL MALYA ROAD 51 46 97 10 14 241120106035 ASMATAZIEN FAROOQ AHMED 6 BEL HIGH SCHOOL JALAHALLI 46 48 94 11 15 241120106037 G ATHREYA DATTA MR GANESHA MURTHI 1 BEL HIGH -

Low Resolution

No. 102 June 2021 IAMGIAMG NewsletterNewsletter Official Newsletter of the International Association for Mathematical Geosciences Contents ith the Covid-19 pandemic Wfar from over, most Announcement of the 2021 IAmG AwArds ......................... 1 scientific meetings have been PresIdent’s forum .............................................................. 3 postponed or converted to a member news ...................................................................... 3 digital format. While there are nomInAtIons for IAmG AwArds ........................................... 3 certainly benefits to online meetings (I definitely don’t miss multiple memorAndum wIth codA AssocIAtIon ................................ 3 flights each way and jetlag) they tend reseArch center for solId eArth bIG dAtA to lose the personal interactions. It founded At the chInA unIversIty of GeoscIences ........... 4 is difficult for an online conference rememberInG dr. Peter fox - A tItAn In the eArth to replicate the conversations in the scIence InformAtIcs communIty ........................................ 4 hallways between sessions or during a meal that can bring a community Ieee GeoscIence And remote sensInG socIety (Grss) dIs- together and build new connections and tInGuIshed lecturer (dl) ............................................. 4 ideas. If you have any ideas or examples Professor noel cressIe nAmed A fellow of the of how the IAMG could work to bring the royAl socIety of new south Wales................................... 4 community together, please -

Dr. N. Susheela 2. Father's Name : Narayanappa 3. Date of Birth

RESUME 1. Name : Dr. N. Susheela 2. Father’s Name : Narayanappa 3. Date of Birth : 10.06.1970 4. Permanent Address : Mallekuppam (Village) Nangali (Post) Mulbagal (Taluk) Kolar Dist. – 513 132. 5. Nationality & Religion : Indian – Hindu 6. Educational Qualifications : 1. M.A. (Kannada), Bangalore University, Bangalore-1996 2. UGC-NET, 1999 3. Ph.D. (Kannada) Bangalore University Bangalore -2003 7. Title of the thesis : “Kuvempu ravara Natakagalalli Kandu baruva Vycharikathe haagu Saamaajika sangarsha ondu Adhyana” 8. Awards : The Best thesis Award – 2004 9. Present Employment : Associate Professor Dept. of Comparative Dravidian Literature & Philosophy Dravidian University, Kuppam – 517 426. Chittoor District, A.P. 10. Research Experience : 10 Years. 11. Research Guidance : Awarded Degree M.Phil: 01 ¾ Miss. S.H. Kruthika Sree awarded for Phil. Degree under my guidance in the year 2012. Thesis title: Oedipus Mathu Chandrahasa natakagalalli Vidhiya Siddhantha: Ondu Adhyayana ¾ Ph.D. Degrees pursuing: 02 12. Teaching Experience : 1) 3 Years (from01.07.1997 to 10.04.2000) Vivekananda Grameena Samyuktha Padavipurva College, Hulkur, Kolar Dist., Karnataka. 2) As a Assistant Professor in Dravidian University from 18.07.2003 to 18.10.2010. 3) As a Associate Professor in Dravidian University from 19.10.2010 to till date. 13. Seminar Organized ¾ UGC National Seminar on “Feminist Concerns in Modern Kannada and Telugu Literature” organized by the Department of Comparative Dravidian Literature & Philosophy, Dravidian University, Kuppam on 26th & 27th March, 2014. 14. Papers Presented : 25 International : 02 ¾ International Conference on Vocational Education and Training: Professionalism as an inclusive Policy – Status and Challenges organized by Dept. of Adult and Continuing Education, Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati on 20th & 21st February, 2013 Paper: “Vocational Education and Training Initiatives for Women”. -

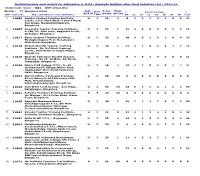

Institutionwise Seat Matrix for Admission to D.Ed - Kannada Medium After Final Selection List - 2011-12 Nodal Code Name : N01 DIET,Urban,Blor

Institutionwise seat matrix for Admission to D.Ed - Kannada Medium after Final Selection List - 2011-12 Nodal Code Name : N01 DIET,Urban,Blor District : 11 : Bangalore Urban Inst. Inst Total Total <------------------Remaining Seats --------------------> G/A/U Intake Alloted SlNo Inst.Code Name and Address of the Institution Type GM SC ST C1 2A 2B 3A 3B Total 1 11005 Amitha Teacher Training Institute , UC 254 84223200 21 C.A.No.2 3rd Main,West of Chord Road, 2nd Stage, Mahalakshmipuram, Bangalore 2 11007 Anugraha Teacher Training Institute , UC 251 124004022 24 # 206/22, 15th main, Nagendra block, Girinagar, Bangalore 3 11017 Bapu Teacher Training Institute , UC 252 104025200 23 Thalaghattapura Post, Kanakapura Main Road, Bangalore 4 11018 Bharat Sevadal Teacher Training UC 251 114203022 24 Institute , Dr. M.C.Modi Training Centre, Ramakrishna Hegde Nagar, Bangalore 5 11019 Bharath Education Society Teacher UC 254 94024200 21 Training , No.27, 16 Main, 4th Block, Jayanagar, Bangalore 6 11026 Diana D.Ed College (TTI) , No 68 UC 254 102203022 21 Chokkanahalli Village,Jakkur Post, Hegdenagar Main Road,Yelahanka Hobli, Bangalore 7 11027 Dist.Institute of Edn.and Training , GC 5050 00000000 0 B'lore Urban,No16,16th Cross,19th Main, Kenchenahalli, Rajarajeshwarinagar, Bangalore 8 11030 East West T.C.H.College , 2nd Stage, UC 4510 145226222 35 Rajajinagar, Bangalore 9 11031 Fathima Teachers Training Institute AF 3030 00000000 0 for Women , 91/1,Coles Road, Frazer Town, Bangalore 10 11045 Kaginele Mahasamsthana UC 401 197117022 39 Kanakagurupeeta T.T.I, 5th Main Muneshwaralayout, Harinagar Cross,KonanaKunte, Bangalore 11 11047 Kanaka Teacher Training Institute , UC 250 123114202 25 Donkalla, Srinivasa Nagara, , Bangalore 12 11062 Maha Bodhi T.T.I , , Nagavara, UC 302 144123022 28 Bangalore 13 11064 Malathesha Education UC 253 94004221 22 Socaiety(M.E.S.T.T.I) , MES Convent, Moodala Palya, Canara Bank Colony, Nagarabhavi Road, Vijayanagar, Bangalore 14 11065 Mathrushri Yallamma Huchchappa UC 251 114223101 24 Ayyanavar, D.Ed. -

Rs in Lakhs SL NO 1 KOLAR Repair and Spares for 66 KV Circuit

TL & SS KOLAR R & M WORKS UNDER 74.110(R&M TO PLANT AND MACHINERY) TO BE TAKEN UP DURING FY 2020-21 Rs in Lakhs Name of the station, SL NO Nomenclature Cost voltage class & division Repair and spares for 66 KV Circuit breaker at 66/11 KV 1 KOLAR 1.00 MUSS Vemagal, Spares and Overhauling of breakers 66/11 kV 2 KOLAR 0.50 S.M.Mangala Repair and spares for 66 KV Circuit breaker at 66/11 KV 3 KOLAR 0.25 TD Halli / MALLSANDRA 4 KOLAR Spares and Overhauling at 66/11 kV Narasapura 0.50 5 KOLAR 66kV spare PT 1 no. at 66/11 kV Narasapura 0.61 Replacement of flurosent lamp of control room and 11KV 6 KOLAR 0.15 breaker shead at 66/11 KV MUSS Sugatur. 66kV CT 400-200/1-1A spare, LA spare 60kA -heavy 7 KOLAR 1.50 duty at 66/11kV MUSS Avani Repair and spares for 66 KV Circuit breaker at 66/11kV 8 KOLAR 0.50 MUSS Addagal M.N.Hally O/G Line-2 66kv breakerspring charging was 9 KOLAR 0.15 not work in remotly at 66/11kV MUSS Tayalur 10 KOLAR Spares and Overhauling at 66/11kV MUSS Tayalur 0.50 11 KOLAR Replacement of ACDB,DCDB at 66/11kV MUSS Tayalur 2.00 12 KOLAR Spares and overhauling at 66/11kV MUSS Mudiyanur 1.00 13 KOLAR 66KV Spare PT 1No at 66/11kV MUSS Mudiyanur 0.61 Repair,Spares and Overhauling of 66KV capacitor bank 14 KOLAR 0.75 SF6 circuit breaker 66/11 kV MUSS Mulbagal Overhauling of 66 kv isolators 66/11kV MUSS 15 KOLAR 0.30 Dalasanur Service,Spares and Overhauling 66/11 kV MUSS 16 KOLAR 1.00 Srinivasapura 17 KOLAR 66kV spare PT 1 no 66/11 kV MUSS Srinivasapura 0.61 18 KOLAR Spares and Overhauling 66/11 kV MUSS Yeldur 0.50 Rs in Lakhs Name -

Four Ana and One Modem House: a Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery

I Four Ana and One Modem House: A Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery Andrew Stephen Nelson Denton, Texas M.A. University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, December 2004 B.A. Grinnell College, December 2000 A Disse11ation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2013 II Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: An Intellectual Journey to the Urban Periphery 1 Part I: The Alienation of Farm Land 23 Chapter 2: From Newar Urbanism to Nepali Suburbanism: 27 A Social History of Kathmandu’s Sprawl Chapter 3: Jyāpu Farmers, Dalāl Land Pimps, and Housing Companies: 58 Land in a Time of Urbanization Part II: The Householder’s Burden 88 Chapter 4: Fixity within Mobility: 91 Relocating to the Urban Periphery and Beyond Chapter 5: American Apartments, Bihar Boxes, and a Neo-Newari 122 Renaissance: the Dual Logic of New Kathmandu Houses Part III: The Anxiety of Living amongst Strangers 167 Chapter 6: Becoming a ‘Social’ Neighbor: 171 Ethnicity and the Construction of the Moral Community Chapter 7: Searching for the State in the Urban Periphery: 202 The Local Politics of Public and Private Infrastructure Epilogue 229 Appendices 237 Bibliography 242 III Abstract This dissertation concerns the relationship between the rapid transformation of Kathmandu Valley’s urban periphery and the social relations of post-insurgency Nepal. Starting in the 1970s, and rapidly increasing since the 2000s, land outside of the Valley’s Newar cities has transformed from agricultural fields into a mixed development of planned and unplanned localities consisting of migrants from the hinterland and urbanites from the city center. -

Management Problems and Practices of Asian Graduate Students at Oregon State University

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF FELITA NACINO SALCEDO for the MASTER OF SCIENCE (Name) (Degree) in HOME MANAGEMENT presented on May 5, 1967 (Major) (Date) Title: MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS AND PRACTICES OF ASIAN GRADUATE STUDENTS AT OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY Abstract approved Redacted for Privacy Martha Plonk This study explored the management problems and practices of 41 Asian graduate students at Oregon State University. The stu- dents were asked to indicate their management problems and practices of food, clothing, and money, their housing conditions, their problems in finding recreation and transportation, and their problems in their academic work and in practicing their religion. All students were enrolled in the University at the time of the interview. Of the group, 25 were males and 16 were females. Twenty -eight were working for their Master's degrees and 10 were working for a Doctor's degree; three students were taking graduate courses but not working for degrees. When the students were asked about their food managment problems and practices, 35 students indicated that they prepared their own meals, while three students ate with American families, two ate in boarding houses, and one in a cooperative. More than half of the 35 students who cooked their own meals planned them depending on what they had on hand in kitchen cabinets and in the refrigerator. Over one -half of these 35 students shopped for food once a week; however 19 made no shopping list of groceries to buy. Twenty -one of the 41 students had received or were receiving native foods from their own countries . -

Foundation University Medical College, Islamabad (MBBS)

Foundation University Medical College, Islamabad (MBBS) S# Candidate ID Name CNIC/NICOP/Passport Father Name Aggregate Category of Candidate 1 400199 Hamzah Naushad Siddiqui 421015-976630-1 Naushad Abid 95 Foreign Applicant 2 400181 Mohammad Ammar Ur Rahman 352012-881540-7 Mobasher Rahman Malik 95 Foreign Applicant 3 302699 Muhammad Ali Abbasi 61101-3951219-1 Iftikhar Ahmed Abbasi 93.75 Local Applicant 4 400049 Ahmad Ittefaq AB1483082 Muhammad Ittefaq 93.54545455 Foreign Applicant 5 400206 Syed Ryan Faraz 422017-006267-9 Syed Muhammad Faraz Zia 93.45454545 Foreign Applicant 6 400060 Heba Mukhtar AS0347292 Mukhtar Ahmad 93.27556818 Foreign Applicant 7 300772 Manahil Tabassum 35404-3945568-6 Tabassum Habib 93.06818182 Local Applicant 8 400261 Syed Fakhar Ul Hasnain 611017-764632-7 Syed Hasnain Ali Johar 93.05113636 Foreign Applicant 9 400210 Muhammad Taaib Imran 374061-932935-3 Imran Ashraf Bhatti 92.82670455 Foreign Applicant 10 400119 Unaiza Ijaz 154023-376796-6 Ijaz Akhtar 92.66761364 Foreign Applicant 11 400344 Huzaifa Ahmad Abbasi 313023-241242-3 Niaz Hussain Abbasi 92.34943182 Foreign Applicant 12 400218 Amal Fatima 362016-247810-6 Mohammad Saleem 92.29545455 Foreign Applicant 13 400130 Maham Faisal BZ8911483 Faisal Javed 92.20738636 Foreign Applicant 14 400266 Ayesha Khadim Hussain 323038-212415-6 Khadim Hussain 92.1875 Foreign Applicant 15 400038 Huzaifa 312029-865960-9 Anwar Ul Haq 92.01988636 Foreign Applicant 16 400002 Manahil Imran 352004-694240-4 Imran Khalid 91.80397727 Foreign Applicant 17 400037 Nawal Habib 544007-020391-6 -

Newsletter Sept

Vol 13 | No. 1 September, October, November 2018 Dear Member, 27th November, 2018 It gives me immense pleasure to connect with you through the BCC&I Newsletter society and the environment in general. The activities of the year ahead will get for the very first time as the President of this historic Institution. At the outset, structured accordingly. may I take this opportunity to convey my seasons greetings and good wishes to you all. With the recent signing of MoU with WEBEL for setting up an incubation centre for startups at Webel Bhavan and special focus on the States MSME sector, your On the macroeconomic level, this year has been sort of a roller coaster ride. In Chamber has its tasks clearly cut out this year. Initiatives aimed at development spite of many debates and discussions, the Indian Economy remained one of the and growth of the States MSME sector to make this sector comparable to the best best performer amongst large economies globally. Teething difficulties in the new in the world are being taken up. To enable successful development of this sector, GST, high and rising real interest rates, an intensifying overhang from the TBS cutting edge technologies should be made available to them and this would call challenge, and sharp falls in certain food prices that impacted agricultural incomes for major skill upgradation. Towards this end a Centre of Excellence for the States are some of the issues confronting the economy. Simmering differences between MSME Sector has been planned by your Chamber in partnership with the Indo- the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Central Government over issues of public German Chamber of Commerce to provide expert services and consultation.