Report of the Earlier Finance Commissions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

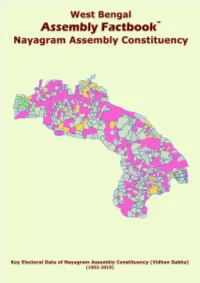

Nayagram Assembly West Bengal Factbook | Key Electoral Data of Nayagram Assembly Constituency | Sample Book

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-220-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-761-5 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 190 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-36 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Villages by Population 37-38 Size | Sex Ratio (Total & 0-6 Years) -

List of Municipalities Sl.No

LIST OF MUNICIPAL BODIES WHERE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD IN THE MIDDLE OF 2010 SL.NO. DISTRICT NAME OF MUNICIPALITY 1 Cooch Behar Municipality 2 Tufanganj Municipality Cooch Behar 3 Dinhata Municipality 4 Mathabhanga Municipality 5 Jalpaiguri Jalpaiguri Municipality 6 English Bazar Municipality Malda 7 Old Malda Municipality 8 Murshidabad Municipality 9 Jiaganj-Azimganj Municipality 10 Kandi Municipality Murshidabad 11 Jangipur Municipality 12 Dhulian Municipality 13 Beldanga Municipality 14 Nabadwip Municipality 15 Santipur Municipality 16 Ranaghat Municipality 17Nadia Birnagar Municipality 18 Kalyani Municipality 19 Gayeshpur Municipality 20 Taherpur Municipality 21 Kanchrapara Municipality 22 Halishar Municipality 23 Naihati Municipality 24 Bhatpara Municipality 25North 24-Parganas Garulia Municipality 26 North Barrackkpore Municipality 27 Barrackpore Municipality 28 Titagarh Municipality 29 Khardah Municipality \\Mc-4\D\Munc. Elec-2010\LIST OF MUNICIPALITIES SL.NO. DISTRICT NAME OF MUNICIPALITY 30 Kamarhati Municipality 31 Baranagar Municipality 32 North Dum Dum Municipality 33 Bongaon Municipality 34 Gobardanga Municipality 35North 24-Parganas Barasat Municipality 36 Baduria Municipality 37 Basirhat Municipality 38 Taki Municipality 39 New Barrackpore Municipality 40 Ashokenagar-Kalyangarh Municipality 41 Bidhannagar Municipality 42 Budge Budge Municipality 43South 24-Parganas Baruipur Municipality 44 Jaynagar-Mazilpur Municipality 45 Howrah Bally Municipality 46 Hooghly-Chinsurah Municipality 47 Bansberia Municipality 48 Serampore Municipality 49 Baidyabati Municipality 50 Champadany Municipality 51 Bhadreswar Municipality Hooghly 52 Rishra Municipality 53 Konnagar Municipality 54 Arambagh Municipality 55 Uttarpara Kotrung Municipality 56 Tarakeswar Municipality 57 Chandernagar Municipal Corporation 58 Tamluk Municipality Purba Medinipur 59 Contai Municipality 60 Chandrakona Municipality 61 Ramjibanpur Municipality 62Paschim Medinipur Khirpai Municipality 63 Kharar Municipality 64 Khargapur Municipality 65 Ghatal Municipality \\Mc-4\D\Munc. -

Panchayat Samity Medinipur 8 Pm Paschim Medinipur, Pin - 721121

List of Govt. Sponsored Libraries in the district of PASCHIM MEDINIPUR Name of the Workin Building Building Building Sl. Name of the Gram Panchayat / Block/ Panchayat Telephone No Type of Year of Year of Name Address District Librarian as on g Own or Kachha / Electrified No. Village / Ward No. Ward No. Samity/ Municipality (If any) Library Estab. Spon. 01.04.09 Hours Rented Pacca or Not At+ P.O. - Midnapore, District Library, Midnapore Paschim 03222 - Manas Kr. Sarkar, 1 pm - 1 Dist.: Paschim Medinipur, Pin - Ward No - 5 Ward No - 5 District 1956 1956 Own Pacca Electified Midnapur Municipality Medinipur 263403 In Charge 8 pm 721101 At + P.O. - Khirpai, Dist. - 12noo Halwasia Sub-Divisional Paschim 03225- Sub - 2 Paschim Medinipur, Ward No - 1 Ward No - 1 Khirpai Municipality Ajit Kr. Dolai 1958 1958 n - Own Pacca Electified Library Medinipur 260044 divisional Pin - 721232 7pm Vill - Kharida, P.O. - Kharagpur, Milan Mandir Town Kharagpur Paschim 1 pm - 3 Dist.: Paschim Medinipur, Pin - Ward No - 12 Ward No - 12 Tarapada Pandit Town 1944 1981 Own Pacca Electified Library Municipality Medinipur 8 pm 721301 At - Konnagar, P.O. - Ghatal,Dist.: Paschim 03225 - Debdas 11 am - 4 Ghatal Town Library Ward No - 15 Ward No - 15 Ghatal Municipality Town 1981 1981 Own Pacca Electified Paschim Medinipur, Pin - 721212 Medinipur 256345 Bhattacharya 6 pm Alapani Subdivisional At + P.O.- Jhargram, Dist.: Jhargram Paschim Rakhahari Kundu Sub - 1 pm - 5 Ward No - 14 Ward No - 14 1957 1962 Own Pacca Electified Library Paschim Medinipur, Pin 721507 Municipality Medinipur Lib. Asstt. divisional 8 pm Vill - Radhanagar, P.O. -

Star Campaigners of Lndian National Congress for West Benqal

, ph .230184s2 $ t./r. --g-tv ' "''23019080 INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 24, AKBAR ROAD, NEW DELHI'110011 K.C VENUGOPAL, MP General Secretary PG-gC/ }:B U 12th March,2021 The Secretary Election Commission of lndia Nirvachan Sadan New Delhi *e Sub: Star Campaigners of lndian National Congress for West Benqal. 2 Sir, The following leaders of lndian National Congress, who would be campaigning as per Section 77(1) of Representation of People Act 1951, for the ensuing First Phase '7* of elections to the Legislative Assembly of West Bengat to be held on 2ffif M-arch br,*r% 2021. \,/ Sl.No. Campaiqners Sl.No. Campaiqners \ 1 Smt. Sonia Gandhi 16 Shri R"P.N. Sinqh 2 Dr. Manmohan Sinqh 17 Shri Naviot Sinqh Sidhu 3 Shri Rahul Gandhi 18 ShriAbdul Mannan 4 Smt. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra 19 Shri Pradip Bhattacharva w 5 Shri Mallikarjun Kharqe 20 Smt. Deepa Dasmunsi 6 ShriAshok Gehlot 21 Shri A.H. Khan Choudhary ,n.T 7 Capt. Amarinder Sinqh 22 ShriAbhiiit Mukheriee 8 Shri Bhupesh Bhaohel 23 Shri Deependra Hooda * I Shri Kamal Nath 24 Shri Akhilesh Prasad Sinqh 10 Shri Adhir Ranian Chowdhury 25 Shri Rameshwar Oraon 11 Shri B.K. Hari Prasad 26 Shri Alamqir Alam 12 Shri Salman Khurshid 27 Mohd Azharuddin '13 Shri Sachin Pilot 28 Shri Jaiveer Sherqill 14 Shri Randeep Singh Suriewala 29 Shri Pawan Khera 15 Shri Jitin Prasada 30 Shri B.P. Sinqh This is for your kind perusal and necessary action. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, IIt' I \..- l- ;i.( ..-1 )7 ,. " : si fqdq I-,. elS€ (K.C4fENUGOPAL) I t", j =\ - ,i 3o Os 'Ji:.:l{i:,iii-iliii..d'a !:.i1.ii'ji':,1 s}T ji}'iE;i:"]" tiiaA;i:i:ii-q;T') ilem€s"m} il*Eaacr:lltt,*e Ge rt r; l-;a. -

Nadia Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/56 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL HOGALBERIA ADARSHA AYADANGA SHIKSHANIKETAN, ROAD,HOGALBARIA HOGALBERIA ADARSHA 1 123204713031 ABHIJIT SARKAR NADIA 19101007604 VILL+P.O- NADIA M SC NONE 49 23 72 ,HOGALBARIA , SHIKSHANIKETAN HOGOLBARIA DIST- NADIA 741122 NADIA W.B, PIN- 741122 KARIMPUR JAGANNATH HIGH BATHANPARA,KARI ABHIK KUMAR KARIMPUR JAGANNATH SCHOOL, VILL+P.O- 2 123204713013 MPUR,KARIMPUR , NADIA 19101001003 NADIA M GENERAL NONE 72 62 134 BISWAS HIGH SCHOOL KARIMPUR DIST- NADIA 741152 NADIA W.B, PIN- 741152 CHAKDAHA RAMLAL MAJDIA,MADANPUR, CHAKDAHA RAMLAL ACADEMY, P.O- 3 123204703069 ABHIRUP BISWAS CHAKDAHA , NADIA NADIA 19102500903 NADIA M GENERAL NONE 68 72 140 ACADEMY CHAKDAHA PIN- 741245 741222, PIN-741222 KRISHNAGANJ,KRIS KRISHNAGANJ A.S HNAGANJ,KRISHNA KRISHNAGANJ A.S HIGH HIGH SCHOOL, 4 123204705011 ABHISHEK BISWAS NADIA 19100601204 NADIA M SC NONE 59 54 113 GANJ , NADIA SCHOOL VILL=KRISHNAGANJ, 741506 PIN-741506 KAIKHALI HARITALA BAGULA PURBAPARA HANSKHALI HIGH SCHOOL, VILL- BAGULA PURBAPARA 5 123204709062 ABHRAJIT BOKSHI NADIA,HARITALA,HA NADIA 19101211705 BAGULA PURBAPARA NADIA M SC NONE 74 56 130 HIGH SCHOOL NSKHALI , NADIA P.O-BAGULA DIST - 741502 NADIA, PIN-741502 SUGAR MILL GOVT MODEL SCHOOL ROAD,PLASSEY GOVT MODEL SCHOOL NAKASHIPARA, PO 6 123204714024 ABU SOHEL SUGAR NADIA 19100322501 NADIA M GENERAL NONE 66 39 105 NAKASHIPARA BETHUADAHARI DIST MILL,KALIGANJ , NADIA, PIN-741126 NADIA 741157 CHAKDAHA RAMLAL SIMURALI,CHANDUR CHAKDAHA RAMLAL ACADEMY, P.O- 7 123204702057 ADIPTA MANDAL IA,CHAKDAHA , NADIA 19102500903 NADIA M SC NONE 67 46 113 ACADEMY CHAKDAHA PIN- NADIA 741248 741222, PIN-741222 NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.2/56 GOVT. -

October 2015

VOL 11 | No. 05 Aug, Sep -Oct, 2015 from the desk of the PRESIDENT Dear Member, 9th October, 2015 Our heartiest greetings to you and your family and for everyone in Bengal for the upcoming seasons! This is my first message to you after having been elected President PT, Entertainment Tax, and Entry Tax. It is one of the only 3 States of this august and historic institution, and I am delighted to share to issue a single Tax ID to cover all State taxes. Additionally, the with you that your Chamber has embraced the new year with great State has exempted 49 industries/activities from pollution control verve. Plans for the year are already being implemented, and each board clearances as a prerequisite to start business. They have also week is witnessing several programmes and activities, which are come up with a single window (Shilpa Sathi) system for large being undertaken almost simultaneously. industries and MSME Facilitation Centre (MFC) for MSMEs. This year the survey was based on 98 points, next year the benchmark We have embarked on new ventures focused on capital formation would be raised by introducing a 330-point action plan on which the together with inclusive growth and have pledged to work with the states have to work. We offer our wholehearted support to the State Government of West Bengal in the latter’s endeavour to bring about Government to address these issues, to trigger a participatory and inclusive growth along with a pro-business environment. In this knowledge-driven reform process and bring West Bengal up to the endeavour, we are meeting with the Government at various levels top 3 States in the next year's survey. -

National Level Webinar Organised by Department of Botany and IQAC, Chakdaha College “Challenges in Environmental Microbiology”

CHAKDAHA COLLEGE (Affiliated to University of Kalyani, West Bengal) NAAC Accredited with ‘B+’ National Level Webinar Organised by Department of Botany and IQAC, Chakdaha College “Challenges in Environmental Microbiology” Free st Registration!!! 31 August, 2020 11 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. (IST) GUEST OF CHIEF GUEST RESOURCE PERSONS HONOUR Prof. (Dr.) Sankar Kumar Ghosh Dr. Chandan Sengupta Dr. Ranadhir Chakraborty Dr. Bernard F. Rodrigues Senior Professor (Retired) Senior Professor Hon’ble Vice-Chancellor Senior Professor Deptt. of Botany Deptt. of Bio-Technology Deptt. of Botany University of Kalyani, W.B. University of Kalyani University of North Bengal Goa University W.B. W.B. Goa PATRON REGISTRATION DETAILS Joint Convenor HOW TO PARTICIPATE Dr. Anjan Sengupta, Associate Professor, Deptt. of Botany & **Register through Google Registration form Dr. Ananya Roy Chowdhury Assistant Professor & HOD, Deptt. of Botany https://forms.gle/gTTY5btSWY7CP8Hn6 IQAC Co-Ordinator Dr. Arun Kumar Nandi, Associate Professor, Deptt. of Last date of Registration: 30th August, 2020 Economics **Join the WhatsApp group Deputy Convenor Dr. Nabanita Chattopadhyay, SACT, Deptt. of Botany INSTRUCTIONS TO Technical Advisor PARTICIPANTS Dr. Anirban Banerjee, Assistant Professor, Deptt. of Dr. Swagata Das Mohanta Zoology Hon’ble Principal Programme Host **Google meeting code, YouTube link, Chakdaha College Dr. Mintu Debnath, Assistant Professor, Deptt. of Facebook link, Feedback link will be provided Physics W.B. st on 31 August,2020 in WhatsApp group. Special thanks to: Ms. Adrita Banerjee, Ms. Bratati **** Participants must have Smart Mondal, Ms. Priyanka Das, SACT, Deptt. of Botany Phone/Tab/Laptop/Desktop with internet ****** Technical support CONTACT: facility. Mr. Anip Roy, Non-Teaching Staff *****Registration and feedback +91 7003909208, submission are mandatory to get the e- ***WITH CORDIAL SUPPORT OF ALL TEACHING AND certificate. -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

DEVELOPMENT of PUBLIC LIBRARIES in the DISTRICT of PURULIA: a STUDY DEBDAS MONDAL [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Summer 5-10-2019 DEVELOPMENT OF PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE DISTRICT OF PURULIA: A STUDY DEBDAS MONDAL [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons MONDAL, DEBDAS, "DEVELOPMENT OF PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE DISTRICT OF PURULIA: A STUDY" (2019). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 2740. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2740 DEVELOPMENT OF PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE DISTRICT OF PURULIA: A STUDY Debdas Mondal Librarian, D.A.V Model School, I.I.T Kharagpur,W.B. [email protected] Kartik Chandra Das Librarian,D.A.V Public School,Haldia [email protected] Abstract The scope of the present review is to cogitate the Public Library scenario in the district of purulia, W.B. It also would reflect their location according to their year of set up and year of sponsorship. The allocation is shown Sub-div, block, Municipal area and Panchayat area wise. The study also focuses the Public Library movement in Purulia district with a conclusion about the necessity of setting up of a public library and recruiting librarians for a well informed society. Keywords: Public Library, Development of Public Library, Purulia District. 1. Introduction In the present era public libraries are the basic units which can provide for the collection of information much needed by the local community where they are set up. This will serve as a gateway of knowledge and information and will enhance opportunity for lifelong learning for the community, which will further help in independent decision making of individuals in the society. -

Howrah, West Bengal

Howrah, West Bengal 1 Contents Sl. No. Page No. 1. Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2. District overview ……………………………………………………………………………… 5-16 3. Hazard , Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis a) Seasonality of identified hazards ………………………………………………… 18 b) Prevalent hazards ……………………………………………………………………….. 19-20 c) Vulnerability concerns towards flooding ……………………………………. 20-21 d) List of Vulnerable Areas (Village wise) from Flood ……………………… 22-24 e) Map showing Flood prone areas of Howrah District ……………………. 26 f) Inundation Map for the year 2017 ……………………………………………….. 27 4. Institutional Arrangements a) Departments, Div. Commissioner & District Administration ……….. 29-31 b) Important contacts of Sub-division ………………………………………………. 32 c) Contact nos. of Block Dev. Officers ………………………………………………… 33 d) Disaster Management Set up and contact nos. of divers ………………… 34 e) Police Officials- Howrah Commissionerate …………………………………… 35-36 f) Police Officials –Superintendent of Police, Howrah(Rural) ………… 36-37 g) Contact nos. of M.L.As / M.P.s ………………………………………………………. 37 h) Contact nos. of office bearers of Howrah ZillapParishad ……………… 38 i) Contact nos. of State Level Nodal Officers …………………………………….. 38 j) Health & Family welfare ………………………………………………………………. 39-41 k) Agriculture …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 l) Irrigation-Control Room ………………………………………………………………. 43 5. Resource analysis a) Identification of Infrastructures on Highlands …………………………….. 45-46 b) Status report on Govt. aided Flood Shelters & Relief Godown………. 47 c) Map-showing Govt. aided Flood -

Inventory of Soil Resources of Howrah District, West Bengal State Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques

Inventory of Soil Resources of Howrah District, West Bengal State Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques ABSTRACT 1. Survey Area : Howrah District, West Bengal State 2. Geographical : 22°12′ N and 22°47′ N latitudes and between 88°37′ E Extent and 87°50′ E longitudes 3. Agro Climatic : Lower Gangetic Plain (Zone no. III as per planning Region commission) 4. Total area : 146701 ha. 5. Kind of Survey : Soil Resources Mapping using remote sensing techniques. 6. Base map : a) IRS – ID Geocoded Satellite Imagery (1: 50000 scale) b) SOI –toposheet (1:50000 scale) 7. Scale of Mapping : 1 : 50000 8. Period of Survey : 2013-14 9. Soil Series association mapped and their respective area Map Mapping Area S.NO. Symbol Uuit Soil Association Area (ha) (%) 1 1 ALb1a1 Sluria-Hoglar 15180 10.35 2 10 ALb2b1 Amta-Chinsura 1792 1.22 3 11 ALb1d1 Nampala-Khalna 2072 1.41 4 12 ALg3a1 Bagnan-Betai Amta 2084 1.42 5 13 ALe3a1 Goindpur-Betai Amta 3263 2.22 6 2 ALb1a2 Mansma-Dhaudhali 13023 8.88 7 3 ALb1a3 Chandpur-Khalna 15151 10.33 Khalna-Najekhan- 8 4 ALb1a4 Mansinghapur 17728 12.08 9 5 ALn2a1 Mainan-Kandulia-Haridhara 6852 4.67 10 6 ALb2a1 Uluberia-Dhaudhali 8347 5.69 11 7 ALb2a2 Udaynarayanpur-Shibanipur 28256 19.26 12 8 ALb2a3 Bansipur-Ichapur 3920 2.67 13 9 ALb2a4 Dhaudhali-Nuniadanga 777 0.53 14 HS Homestead 19481 13.28 15 River River 8382 5.71 16 Tank Tank 383 0.26 17 Water body WB 10 0.01 Grand Total 146701 100 10. -

West Bengal Towards Change

West Bengal Towards Change Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation Research Foundation Published By Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation 9, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 Web :- www.spmrf.org, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone:011-23005850 Index 1. West Bengal: Towards Change 5 2. Implications of change in West Bengal 10 politics 3. BJP’s Strategy 12 4. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 14 Statements on West Bengal – excerpts 5. Statements of BJP National President 15 Amit Shah on West Bengal - excerpts 6. Corrupt Mamata Government 17 7. Anti-people Mamata government 28 8. Dictatorship of the Trinamool Congress 36 & Muzzling Dissent 9. Political Violence and Murder in West 40 Bengal 10. Trinamool Congress’s Undignified 49 Politics 11. Politics of Appeasement 52 12. Mamata Banerjee’s attack on India’s 59 federal structure 13. Benefits to West Bengal from Central 63 Government Schemes 14. West Bengal on the path of change 67 15. Select References 70 West Bengal: Towards Change West Bengal: Towards Change t is ironic that Bengal which was once one of the leading provinces of the country, radiating energy through its spiritual and cultural consciousness across India, is suffering today, caught in the grip Iof a vicious cycle of the politics of violence, appeasement and bad governance. Under Mamata Banerjee’s regime, unrest and distrust defines and dominates the atmosphere in the state. There is a no sphere, be it political, social or religious which is today free from violence and instability. It is well known that from this very land of Bengal, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore had given the message of peace and unity to the whole world by establishing Visva Bharati at Santiniketan.