The 1972 Chouinard Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

Climbing Towards Sustainability

Climbing Towards Sustainability Joseph Muggli, College of St. Benedict |St. Johns University Department of Environmental Studies. Advisors: Derek Larson, Richard Bohannon Type of Climbing Positives Negatives Abstract: Rock Climbing has grown into a popular sport Removable gear/ protection. Gear can get stuck and lost Traditional Aid Climbing amongst the cliff face. Leave No Trace Climbing that is enjoyed by people all over the world. With climb- Born from traditional climb- The Center of Outdoor Ethics has 7 Leave No Trace ing growing more popular, the strain on the environ- (TRAD) ing, deep rooted outdoor Not as secure as the other two. principles that concern any recreational activity in the ment involved is becoming an issue regarding the ethics. Requires a lot of experience outdoors. Of these seven there are that stand out spe- preservation and conservation of these popular loca- Costly to the climber Leaves no trace. cifically for climbing. tions. How does one practice climbing in an environ- Secured/ fixed anchors and Brought climbing into new un- mentally sound way to preserve the future of the sport Sport Climbing 1.) Plan Ahead and Prepare bolts. regulated areas. and to ensure the future of the ecosystems in which (Fixed Anchors) 2.)Camp and Travel on Durable Surfaces. Opens up new areas that are un Leaves a permanent route up climbing takes place? The history of the sport along with 3.) Dispose of Waste Properly -climbable in traditional man- the cliff face. relevant conservation efforts will be able to help shape 4.) Respect Wildlife ners. Replacement of weathered/ a specific set of rules to abide by in order to ensure the 5.) Leave What you Find Provides a safer atmosphere for broken bolts and anchors is sustainability of the outdoor sport. -

2014 AMGA SPI Manual

AMERICAN MOUNTAIN GUIDES ASSOCIATION AMGA Single Pitch Instructor 2014 Program Manual American Mountain Guides Association P.O. Box 1739 Boulder, CO 80306 Phone: 303-271-0984 Fax: 303-271-1377 www.amga.com 1 AMGA Single Pitch Instructor Program © American Mountain Guides Association Participation Statement The American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA) recognizes that climbing and mountaineering are activities with a danger of personal injury or death. Clients in these activities should be aware of and accept these risks and be responsible for their own actions. The AMGA provides training and assessment courses and associated literature to help leaders manage these risks and to enable new clients to have positive experiences while learning about their responsibilities. Introduction and how to use this Manual This handbook contains information for candidates and AMGA licensed SPI Providers privately offering AMGA SPI Programs. Operational frameworks and guidelines are provided which ensure that continuity is maintained from program to program and between instructors and examiners. Continuity provides a uniform standard for clients who are taught, coached, and examined by a variety of instructors and examiners over a period of years. Continuity also assists in ensuring the program presents a professional image to clients and outside observers, and it eases the workload of organizing, preparing, and operating courses. Audience Candidates on single pitch instructor courses. This manual was written to help candidates prepare for and complete the AMGA Single Pitch Instructors certification course. AMGA Members: AMGA members may find this a helpful resource for conducting programs in the field. This manual will supplement their previous training and certification. -

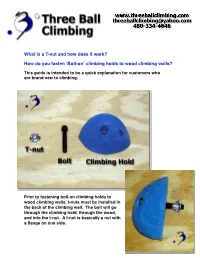

What Is a T-Nut and How Does It Work? How Do You Fasten ʻbolt-Onʼ

What is a T-nut and how does it work? How do you fasten ʻBolt-onʼ climbing holds to wood climbing walls? This guide is intended to be a quick explanation for customers who are brand new to climbing. Prior to fastening bolt-on climbing holds to wood climbing walls, t-nuts must be installed in the back of the climbing wall. The bolt will go through the climbing hold, through the wood, and into the t-nut. A t-nut is basically a nut with a flange on one side. The barrel of the t-nut can fit into a 7/16” hole, but the flange is 1” wide so it cannot fit through the hole. The flange catches the surface of the climbing wall surrounding the 7/16” hole. The Barrel of the T-nut should be recessed behind the front surface of the climbing wall by at least 1/ 4”. Climbing holds must not make di- rect contact with the t-nut. If the climbing hold makes direct con- tact with the t-nut it will eliminate the friction between the surface of the climbing wall and the back of the climbing hold. Climbing holds must have good contact with the climbing wall in order to be secure. Selecting the proper length bolts: Every climbing hold has a different shape and structure. Because of these variations, the depth of the bolt hole varies from one climbing hold to another. Frogs 20 Pack Example: The 20 pack of Frogs Jugs to the right consists of several different shaped grips. -

OUTDOOR ROCK CLIMBING INTENSIVE INTRODUCTION Boulder, CO EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST

www.alpineinstitute.com [email protected] Equipment Shop: 360-671-1570 Administrative Office: 360-671-1505 The Spirit of Alpinism OUTDOOR ROCK CLIMBING INTENSIVE INTRODUCTION Boulder, CO EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST This equipment list is aimed to help you bring only the essential gear for your mountain adventures. Please read this list thoroughly, but exercise common sense when packing for your trip. Climbs in the summer simply do not require as much clothing as those done in the fall or spring. Please pack accordingly and ask questions if you are uncertain. CLIMATE: Temperatures and weather conditions in Boulder area are often conducive to great climbing conditions. Thunderstorms, however, are somewhat common and intense rainstorms often last a few hours in the afternoons. Daytime highs range anywhere from 50°F to 80°F. GEAR PREPARATION: Please take the time to carefully prepare and understand your equipment. If possible, it is best to use it in the field beforehand. Take the time to properly label and identify all personal gear items. Many items that climbers bring are almost identical. Your name on a garment tag or a piece of colored electrical tape is an easy way to label your gear; fingernail polish on hard goods is excellent. If using tape or colored markers, make sure your labeling method is durable and water resistant. ASSISTANCE: At AAI we take equipment and its selection seriously. Our Equipment Services department is expertly staffed by climbers, skiers and guides. Additionally, we only carry products in our store have been thoroughly field tested and approved by our guides. This intensive process ensures that all equipment that you purchase from AAI is best suited to your course and future mountain adventures. -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines Compiled for the Victorian Climbing Community Revision: V04 Published: 15 Sept 2020 1 Contributing Authors: Matthew Brooks - content manager and writer Ashlee Hendy Leigh Hopkinson Kevin Lindorff Aaron Lowndes Phil Neville Matthew Tait Glenn Tempest Mike Tomkins Steven Wilson Endorsed by: Crag Stewards Victoria VICTORIAN CLIMBING MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES V04 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 2 Foreword - Consultation Process for The Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines The need for a process for the Victorian climbing community to discuss widely about best rock-climbing practices and how these can maximise safety and minimise impacts of crag environments has long been recognised. Discussions on these themes have been on-going in the local Victorian and wider Australian climbing communities for many decades. These discussions highlighted a need to broaden the ways for climbers to build collaborative relationships with Traditional Owners and land managers. Over the years, a number of endeavours to build and strengthen such relationships have been undertaken; Victorian climbers have been involved, for example, in a variety of collaborative environmental stewardship projects with Land Managers and Traditional Owners over the last two decades in particular, albeit in an ad hoc manner, as need for such projects have become apparent. The recent widespread climbing bans in the Grampians / Gariwerd have re-energised such discussions and provided a catalyst for reflection on the impacts of climbing, whether inadvertent or intentional, negative or positive. This has focussed considerations of how negative impacts on the environment or cultural heritage can be avoided or minimised and on those climbing practices that are most appropriate, respectful and environmentally sustainable. -

Experience the Thrill of Heights

EXPERIENCE THE THRILL OF HEIGHTS The multi-way splitter is not for sale in the US. a brand of 2 Walltopia is the world leader in climbing walls manufacturing and active entertainment attractions with more than 1800 projects in over 70 countries. Our Active Entertainment product line evolved from our experience in the climbing wall industry and the natural human craving for play. We were driven by the desire to transform physical activity into amusing and purposeful play, suitable and entertaining for everyone, with no need of specific sport preparation and minimum equipment required for the participants. Providing versatile experience, in their core our products share one and the same goal. They help us get active and encourage us to spend more time with our family and friends in a meaningful, present way. That’s what we call active entertainment. 4 EXPERIENCE THE THRILL OF HEIGHTS Walltopia Ropes Courses challenge flexibility, balance and strength in a thrill-boosting way, while ensuring maximum safety in conjunction with eurocode safety standards. All our ropes courses offer a wide range of difficulty levels that appeal to both children and adults. The brand’s attractions are appropriate for participants as young as five years old. The multi-way splitter is not for sale in the US. OVERVIEW Key points MULTI-DEMOGRAPHIC APPEAL FLEXIBLE BUSINESS MODELS The difficulty of each obstacle can be Our courses accommodate linear tailored to preference or to specific per-ride or multi-directional hourly- age groups. ticketed operation models. OPERATION EFFICIENCY EASY INTEGRATION Highest manufacturing and safety Flexible designs & extensive theming standards ensure hassle-free operation options allow for easy integration while and low maintenance costs. -

Ordinary Meeting Held on 23/11/2020

Queensland Climbing Management Guidelines Compiled for the Queensland Climbing Community 1 Acknowledgement We proudly acknowledge Queensland’s First Nations peoples and their ongoing strength in practising one of the world’s oldest living cultures. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands and waters on which we live, work, recreate, and pay our respect to their Elders past, present and future. We recognise that there are long-lasting, far-reaching and intergenerational consequences of colonisation, dispossession and separation from Country. We acknowledge that the impact and structures of colonisation still exist today, and that all peoples have a responsibility to transform its systems and services so that Aboriginal Queenslanders can be the ones to hold decision-making power over the matters that affect their lives. We also acknowledge that Aboriginal self-determination is a human right enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and recognise the hard work of many generations of Aboriginal people who have fought for this right to be upheld. This document is intended to act as a guide for the Queensland Public Service, Volunteer organisations, and for personal action, to enable Aboriginal self-determination and provide possible solutions to ensure protection of valuable Cultural Heritage and the Environment for the future of all. QUEENSLAND CLIMBING MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES V04 NOVEMBER 2020 2 Foreword - Consultation Process for The Queensland Climbing Management Guidelines The need for a process for the Queensland climbing community to discuss widely about best rock-climbing practices and how these can maximise safety and minimise impacts of crag environments has long been recognised. -

Passive Protection Protection Passive Passive Sicherungen

A chaque fois que vous réformez une pièce de matériel, détruisez- „Verkeilt“ sich die Sicherung, ist die Gefahr geringer, dass sie FRANÇAIS la pour empêcher toute utilisation ultérieure. sich bei Seilzug lockert oder gar herausfällt. NOTICE D’UTILISATION ◆ Zum Entfernen eines Stopper oder Hex aus einem Riss benötigen STOPPERS ET HEXENTRICS D’OCCASION Sie eventuell ein Nut Tool. Vermeiden Sie es, das Kabel häufig North America: Black Diamond Equipment, Ltd. Nous déconseillons vivement l’utilisation de matériel d’occasion. stark zu verbiegen, da es hierbei übermässig belastet wird und 2084 East 3900 South Salt Lake City, UT 84124 AVERTISSEMENT Vous devez connaître les antécédents de votre matériel afin de schliesslich brechen kann. Phone: (801) 278-5533, Fax: (801) 278-5544 Pour l’escalade et l’alpinisme uniquement. pouvoir juger de sa fiabilité. Email: [email protected] L’escalade et l’alpinisme sont des activités EN 12270 : Les Stoppers, Micro Stoppers, Micro Stoppers Offset et Europe: Black Diamond Equipment AG ! Verwenden Sie zum Einhängen in das Kabel immer einen Hexentrics Black Diamond sont conformes à la norme européenne Christoph Merian Ring 7 4153 Reinach, Switzerland dangereuses. Vous devez comprendre et accepter Karabiner. Fädeln Sie niemals Gurtband oder Seil direkt durch EN 12270 relative à l’équipement d’alpinisme et d’escalade – Phone: +41/61 564 33 33, Fax: +41/61 564 33 34 les risques encourus avant de vous engager. Les ein Stopper- oder Hexentric-Kabel. Coinceurs – Exigences de sécurité et méthodes d’essai. Email: [email protected] mineurs et autres personnes dans l’incapacité ! Vermeiden Sie bei der Platzierung von Sicherungen, dass das Asia: Black Diamond Equipment Asia d’assumer cette responsabilité doivent pratiquer MARQUAGES Kabel bei Belastung über scharfe Kanten läuft. -

2010 Metolius Climbing 2

2010 METOLIUS CLIMBING 2 It’s shocking to think that it’s been twenty-five years since we cranked up the Metolius Climbing machine, and 2010 marks our 25th consecutive year in business! Wow! Getting our start in Doug Phillips’ tiny garage near the headwaters of the Metolius River (from where we take our name), none of us could have envisioned where climbing would be in 25 years or that we would even still be in the business of making climbing gear. In the 1980s, the choices one had for climbing equipment were fairly limited & much of the gear then was un-tested, uncomfortable, inadequate or unavailable. Many solved this problem by making their own equipment, the Metolius crew included. 3 (1) Smith Rock, Oregon ~ 1985 Mad cranker Kim Carrigan seen here making Much has changed in the last 2 ½ decades since we rolled out our first products. The expansion we’ve seen has been mind-blowing the 2nd ascent of Latest Rage. Joined by fellow Aussie Geoff Wiegand & the British hardman Jonny Woodward, this was one of the first international crews to arrive at Smith and tear the and what a journey it’s been. The climbing life is so full of rich and rewarding experiences that it really becomes the perfect place up. The lads made many early repeats in the dihedrals that year. These were the days metaphor for life, with its triumphs and tragedies, hard-fought battles, whether won or lost, and continuous learning and growing. when 5.12 was considered cutting edge and many of these routes were projected and a few of Over time, we’ve come to figure out what our mission is and how we fit into the big picture.