Calvin Coolidge a Tale of Two Coolidges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Autobiography-Of-Calvin-Coolidge

The History Public Schools Don’t Teach James Madison wrote that “a people who mean to be their own governors must be armed with the power that knowledge gives”. In “Democracy in America” Alexis de Tocqueville noted that Americans of his day were far more knowledgeable about government and the issues of the day than their counterparts in Europe. Tocqueville wrote “every citizen receives the elementary notions of human knowledge; he is taught, moreover, the doctrines and the evidences of his religion, the history of his country, and the leading features of its Constitution”. The founders knew that only an educated populace, jealous of their rights, would be strong enough to resist the usurpation of their liberties by government. Today many people know nothing of our true history, or the source of our rights. The mission of The Federalist Project is to get people the history public schools don’t teach to motivate them to push back at the erosion of our liberties and restore constitutionally limited small government. What we do: Use social media to better educate Americans on: Our true American History, and what the public schools left out. What History tells us about current events. The Constitution, and why our form of government is the best ever developed. How You Can Support The Federalist Papers Project Engage in the conversation on facebook, twitter and pinterest Refer your friends to our facebook, twitter, and pinterest pages Share our content on a regular basis FREE EBOOKS The Constitution The Complete Federalist Papers The Essential Federalist Papers The Anti-Federalist Papers The Essential Anti-Federalist Papers The Wisdom of George Washington Please visit our website to access our library of 200 + FREE Ebooks on American History and our form of government. -

The Boston Police Strike in the Context of American Labor

Nineteen Nineteen: The Boston Police Strike in the Context of American Labor An Essay Presented by Zachary Moses Schrag to The Committee on Degrees in Social Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree with honors of Bachelor of Arts Harvard College March 1992 Author’s note, 2002 This portion of my website presents "Nineteen Nineteen: The Boston Police Strike in the Context of American Labor." I wrote this essay in the spring of 1992 as my undergraduate honors thesis. I hope that the intervening ten years and my graduate education have helped me produce more sophisticated, better written works of history. But since I posted this thesis on-line several years ago, several websites have linked to the essay as a useful resource on the strike, labor history, and Calvin Coolidge. I therefore intend to keep it on the Web indefinitely. Aside from some minor corrections, this version is identical to the one I submitted, now on file at the Harvard Depository. The suggested citation is, Zachary Moses Schrag, “Nineteen Nineteen: The Boston Police Strike in the Context of American Labor” (A.B. thesis, Harvard University, 1992). Author’s note, March 2012 In the spring of 2011, my website, www.schrag.info, was maliciously hacked, leading me to reorganize that site as historyprofessor.org and zacharyschrag.com. As part of the reorganization, and in honor of the twentieth anniversary of this document’s completion, I have replaced the HTML version of the thesis—created in 1997—with the PDF you are now reading, which I hope is a more convenient format. -

Hclassification

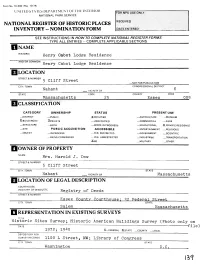

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

4 the AMERICAN and BRITISH CULTURAL APPROACHES The

4 THE AMERICAN AND BRITISH CULTURAL APPROACHES HOW DIFFERENT WAS Japan's cultural approach from those of the United States and Great Britain in the 1920S? Was the same pattern of Sino Japanese interaction reflected in Sino-American and Sino-British interaction during this period? In analyzing the American situation, the chapter first focuses on Sino-American interaction and then examines American views on how the remission could be best used. The British case is then examined in a similar fashion, followed by a comparison of the two ap proaches. THE AMERICAN APPROACH, 1924-1931 The Second American Remission and Sino-American Interaction In December 1908, the United States remitted a portion of its Boxer indem nity to support an educational program comprised of the Chinese Educa tional Mission and T singhua College. While this program continued into the 1920S, there were also calls for the United States to remit the remaining portion of its indemnity for similar purposes. This movement for total re mission was actively advocated by the chairman of the Senate Foreign Rela tions Committee, Henry Cabot Lodge. With the backing of the State De partment, Lodge introduced a resolution for total remission in May 1921. Although the resolution was passed by the Senate in August, it was stalled The American and British Cultural Approaches 93 in the House, whose members feared that approving such an act might en courage the European powers involved in World War I to press the United States for a. similar waiving of their war debts.l When the fear of such a linkage gradually ebbed over the next two years, Lodge re-introduced the remission resolution into Congress in December 1923. -

Coolidge Family Papers 1802-1932

A Guide to the Coolidge Family Papers 1802-1932 Copyright 1995 by the Vermont Historical Society. Revised December 2010. ii Contents Scope and Content Note 1 Biographical Sketch 1 Provenance 2 Related Collections 2 Organization 3 Series Descriptions 4 Inventory 8 I. Coolidge Family Papers 8 II. Calvin G. Coolidge Papers 8 III. Coolidge, John C. 10 IV. Plymouth, Vermont records 14 V. Coolidge, Calvin 16 V. Photographs 18 VI. Miscellaneous 22 iii Coolidge Family Papers, 1802-1932 Doc 215 Scope and Content Note The Coolidge family papers are a collection of correspondence, financial and legal papers, and photographs of the Coolidge family of Plymouth, Vermont, 1802-1932. The focus of the papers is John Coolidge (1845-1926), but other family members and generations are represented as well. Most significant of these is John’s son, President Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933). There is also a substantial amount of material of John's father, Calvin Galusha Coolidge (1815-1878), and, because of the family’s involvement in local government and politics, there are many papers concerning the town of Plymouth. The collection is stored in ten document boxes, Doc 215-221, 390-392, and has oversize material in MS Size B, C, and D. Biographical Sketch Calvin Galusha Coolidge was born September 22, 1815, in Plymouth, Vermont, the son of Calvin and Sarah (Thompson) Coolidge. He married Sarah Almeda Brewer in 1844. They had two children: John Calvin (1845-1926) and Julius Caesar (1851-1870). Calvin G. Coolidge served as justice of the peace, town agent, constable, and selectman for the town of Plymouth. -

Ocm16570871-Mscoll19.Pdf (156.0Kb)

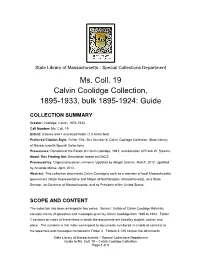

State Library of Massachusetts - Special Collections Department Ms. Coll. 19 Calvin Coolidge Collection, 1895-1933, bulk 1895-1924: Guide COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Coolidge, Calvin, 1872-1933. Call Number: Ms. Coll. 19 Extent: 3 boxes and 1 oversized folder (1.5 linear feet) Preferred Citation Style: Folder Title, Box Number #. Calvin Coolidge Collection. State Library of Massachusetts Special Collections. Provenance: Donation of the Estate of Calvin Coolidge, 1943, and donation of Frank W. Stearns. About This Finding Aid: Description based on DACS. Processed by: Original processor unknown. Updated by Abigail Cramer, March, 2012. Updated by Amanda Morse, April, 2014. Abstract: This collection documents Calvin Coolidge’s work as a member of local Massachusetts government (State Representative and Mayor of Northampton, Massachusetts), as a State Senator, as Governor of Massachusetts, and as President of the United States. SCOPE AND CONTENT The collection has been arranged in two series. Series I: Estate of Calvin Coolidge Materials consists mainly of speeches and messages given by Calvin Coolidge from 1895 to 1924. Folder 1 contains an index to these items in which the documents are listed by subject, author, and place. The numbers in this index correspond to documents numbered in a table of contents to the speeches and messages contained in Folder 2. Folders 3-128 contain the documents State Library of Massachusetts – Special Collections Department Guide to Ms. Coll. 19 – Calvin Coolidge Collection Page 1 of 9 referred to as “Speeches and Messages.” Also included is a folder of typescript copies of letters from Calvin Coolidge between 1919 and 1920, and a folder of statements by Calvin Coolidge made between 1919 and 1921. -

The Brahmins, the Irish and the Boston Police Strike of 1919

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2011 Stratified Boston: The rB ahmins, the Irish and the Boston Police Strike of 1919 Sarah Block Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Block, Sarah, "Stratified Boston: The rB ahmins, the Irish and the Boston Police Strike of 1919" (2011). Honors Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/6 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iv Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the help of a few individuals who supported me throughout the thesis preparation and writing process. First, I would like to thank Professor John Enyeart, who both served as my thesis adviser as well as a member of my defense committee. His expert advice in the field of history and writing has aided me immensely, and he helped me turn this thesis into the best work I have completed during my undergraduate career. Similarly, Professor Leslie Patrick and Professor Chris Ellis acted as the second and third readers of my thesis and as the remainder of my defense committee. I could not have completed this work without their guidance. I am appreciative of the time and dedication all of my readers in helping me through this process, and I could not have done it without all of you. -

An Investigation of John F. Kennedy's, Lyndon B. Johnson's, and Ronald

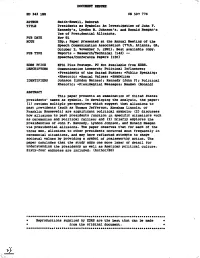

DOCUNENT RESUME ED 343 188 CS 507 774 AUTHOR Smith-Howell, Deborah TITLE Presidents as Symbols: An Investigation of Jcen F. Kennedy's, Lyndon B. Johnson's, and Ronald Reagan's Use of Pressdential Allusions. PUB DATE Nov 91 NOTE 29p.; Paper presented at the Annual Heating of the Speech Communication Association (77th, Atlanta, OA, October 34 Movember 3, 1991). Best available copy. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDBS PEI= NFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Communication 1m:search; Political Influences; *Presidents of the United States; *Public Speaking; *Rhetoric; *Social Values; *Symbolism IDENTIFIERS Johnson (Lyndon Baines); Kennedy (John F); Political Rhetoric; *Presidential Massages; Reagan (Ronald) ABSTRACT This paper presents an examination of United States presidents' names as symbols. In developing the analysis, the paper: (1) reviews multiple perspectives which suggest that allusions to past presidents (such as Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, or Franklin Roosevelt) are significant political symbols; (2) discusses how allasions to past presidents function in specific situatiors such as ceremonies and political rallies; and (3) briefly explores the presidencies of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Ronald Reagan via presidential allusions. The paper observes that for each of the three men, allusions to other presidents occurred most frequently in ceremonial situations, and may have reflected attempts to shape societal values by providing a symbol of praiseworthy action. The paper concludes that the study adds one more layer of detail for understanding the presidency as wel1 as American political culture. Sixty-four endnotes are included. (Author/SO) t********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Annual Report

2016 Annual Report 602 W. Ionia Street • Lansing, Michigan 48933 (517) 487-9539 • www.environmentalcouncil.org 3 100% post-consumer recycled paper Cover Photo: John McCormick, Michigan Nut Photography From the PRESIDENT wo of the Michigan Environmental hire our first-ever agriculture policy TCouncil’s signature achievements director. That means we’ll have greater in 2016 made it clear that, as President capacity to promote state, local and Calvin Coolidge put it, “Nothing federal policies that support Michigan in this world can take the place of in growing a diverse abundance of persistence.” food while promoting the long-term James Clift, our policy director, well-being of our water, wildlife and spent five years doing everything he climate. We’ve long worked to make could to block a state plan to deregulate agriculture more sustainable, but this air emissions of 500 toxic chemicals. is the first time we’ve had a program At times, it looked like a lost cause. But dedicated solely to farm issues. James and MEC never let up, and in Generous financial support March, state officials announced they also made possible a new initiative were dropping the plan. launched in late 2016 to ensure Likewise, our tenacity was key in that families across Michigan enjoy achieving important clean energy safe, affordable drinking water. reforms in the final days of 2016. We’re reaching out to water experts, Lawmakers put forward some Chris Kolb, President community leaders and residents to worrisome proposals during more than learn about the challenges they face two years of negotiations, legislative and the resources they need to advance hearings and bill introductions. -

John and Mary Coolidge

DESCENDANTS if JOHN AND MARY COOLIDGE of WATERTOWN, MASSACHUSETTS 1630 ~y EMMA DOWNING COOLIDGE Chairman, Genealogical Committee of the Coolidge Family Association Author of "At the King's Pleasur-e," "The Dr-tamer," and other booh, plays and historical articles BOSTON WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING COMPANY 32 DERNE STREET Copyrighted, November, 1930, By EMMA DoWI'lt~NG CooLIDGE Thatched roofs still outline the village street of Cottenham, England, leading to the beautiful old church, as in the days of John Coolidge's youth 164 BLosso::--.1 STREET F':tTc:BBlcRO, l>{A,!11-,AQKUSETTS January 21, 1931. Mr. A. F. Donnell c/o Boston Post Boston, ~assachusetts Dear ~r. Donnell: In the Boston Post of last Sunday, January 18th, there is an article headed "Genealogy of Coolidge Family". This came to my desk this ~orning. You knJw I promised you this new edition of the Coolidge genealogy by Miss E~:,12 :80·:.T.ing Coolidge of l~ewton. I had this in my car last week w:1en in BostoE, and also yesterday, but could not find an opportunity to run ir. to see you. I rather delayed sending you this copy, hoping to have an opportunity to autograph it as~Senator~ but perhaps you will find so::ie interest in :1aving the above volume irnr:1ediately, t:i.erefore I am sending sa.'ne to you. I want to thank you again for the nice Coolidge article you wrote on Sunday, September 28th. With kind regards, I beg to remain Very truly, INTRODUCTION It is with pleasure that the author and compiler of .this record of many of the descendants of JOHN and l\fARy CooL maE, COLONISTS, of Watertown, Massachusetts, 1630, presents this volume in November, 1930, during the celebration of the Tercentenary of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay.