Jason Tondro: "ENG 140J: the Superhero Narrative"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Cerebus Rex II: the Second Half

Cerebus Rex II: The Second Half Hello, and welcome to Cerebus Rex II. Written by the Cerebus Fangirl and part by Daniel, it summarizes the second half of Cerebus from issue #150 to #300. It can be found on the internet at http://www.cerebusfangirl.com/rex/ Flight Issue #151 : The novel opens with Cirin in the Papal Library of the Eastern Church looking for books on the One True Ascension. The books that don't meet her criteria are thrown in the Furnaces. So far no books meet her requirements. The demon Khem realizes it has no reason to exist any longer. So it turns into itself and disappears. Cerebus is creating bloody hell in the streets of Iest. Cirin refuses to believe her troops that it is indeed Cerebus. The Judge appears to Death and tells it that it is not Death but a lesser Demon. Death ceases to exist. Lord Julius is sign briefly. Issue #152 : Cerebus fights more Cirinists and (male) on lookers start cheering for "the Pope." They start talking back to the Cirinists. General Norma Swartskof telepathically shows Cirin what Cerebus has been doing. The Black Blossom Lotus magic charm is in the Feld River, the magic leaves it's form and turns into a narrow band of light (the blossom disappears) and two coins that are over 1,400 years old start spinning together in a circle. The report from Cirin is to take Cerebus alive. The General thinks otherwise and orders him KILLED. Issue #153 : Cerebus climbs to a balcony and urges the citizens of Iest that it is the time for Vengeance, for them to grab a weapon, to take back their city and to kill the Cirinists. -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

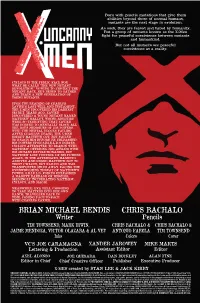

Brian Michael Bendis Chris Bachalo

Born with genetic mutations that give them abilities beyond those of normal humans, mutants are the next stage in evolution. As such, they are feared and hated by humanity. But a group of mutants known as the X-Men fight for peaceful coexistence between mutants and humankind. But not all mutants see peaceful coexistence as a reality. CYCLOPS IS THE PUBLIC FACE FOR WHAT HE CALLS “THE NEW MuTANT REVOLuTION.” VOWING TO PROTECT THE MuTANT RACE, HE’S BEGuN TO GATHER AND TRAIN A NEW GENERATION OF YOUNG MUTANTS. UPON THE READING OF CHARLES XAVIER’S LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT, THE X-MEN UNCOVERED HIS DARKEST SECRET. YEARS AGO, XAVIER DISCOVERED A YOUNG MUTANT NAMED MATTHEW MALLOY, WHOSE ABILITIES WERE SO TERRIFYING THAT XAVIER WAS FORCED TO MENTALLY BLOCK ALL THE BOY’S MEMORIES OF HIS POWERS. WITH THE MENTAL BLOCKS FAILING AFTER CHARLES’ DEATH, THE x-MEN SOUGHT MATTHEW OUT, BUT FAILED TO REACH HIM BEFORE HE UNLEASHED HIS POWERS uPON S.H.I.E.L.D.’S FORCES. CYCLOPS ATTEMPTED TO REASON WITH MATTHEW, OFFERING HIM ASYLUM WITH HIS MUTANT REVOLUTIONARIES, BUT MATTHEW LOST CONTROL OF HIS POWERS AGAIN. IN THE AFTERMATH, MAGNETO ARRIVED AND URGED MATTHEW NOT TO TRUST CYCLOPS, BUT FAILED AND WAS TRANSPORTED MILES AWAY. FACING THE OVERWHELMING THREAT OF MATTHEW’S POWER, S.H.I.E.L.D. FORCES UNLEASHED A MASSIVE BARRAGE OF MISSILES, SEEMINGLY INCINERATING MATTHEW, CYCLOPS, AND MAGIK. MEANWHILE, EVA BELL, CHOOSING TO TAKE MATTERS INTO HER OWN HANDS, TRAVELLED BACK IN TIME, COMING FACE-TO-FACE WITH CHARLES XAVIER. BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS CHRIS BACHALO Writer Pencils TIM TOWNSEND, MARK IRWIN, CHRIS BACHALO & CHRIS BACHALO & JAIME MENDOZA, VICTOR OLAZABA & AL VEY ANTONIO FABELA TIM TOWNSEND Inks Colors Cover VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA XANDER JAROWEY MIKE MARTS Lettering & Production Assistant Editor Editor AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE Editor in Chief Chief Creative Officer Publisher Executive Producer X-MEN created by STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY UNCANNY X-MEN No. -

Proceedings Book 2.Indb

69 Changing Icons: The Symbols of New York City in Film TERRI MEYER BOAKE University of Waterloo These architectural symbols also begin to differ- entiate “new” cities, whose prominent building are entirely contemporary, from “old” cities, whose icons begin to show, even by silhouette, the evo- lution of the architectural style that has come to represent the culture or zeitgeist of the place. The icons of Dubai all reside in the present. The collec- tion of symbols that represents London is capable of placing it in the past through the use of Big Ben or St. Paul’s, or in the present, via the London Eye. Likewise for Paris, the past and present are contrasted through the Eiffel Tower and the Lou- vre Pyramid. Strikingly absent from the New York suite, are the paired rectangular images of the Twin Towers. Without an alternate “modern” icon, the city has lately come to be characterized by notable buildings of the past – The Empire State 1 Fig. 1. Silhouettes of well known City Icons. Building, Statue of Liberty and St. Patrick’s Ca- thedral – leaving the identity of the present, quite THE ICONS OF THE CITY unfi lled. Not that there are no other contempo- rary towers in New York. The Seagram Building, The architectural icons of the City have long served ATT and Citicorp Towers, and new Hearst Building to allow fi lm directors to identify the location of have important places in the creation of modern the primary setting in the fi lm. Whether the fi lm New York. But, situated in midtown, they lack a has been shot in the studio, on location, or been presence on the skyline and can never be ade- created entirely through CGI technologies, these quately charged with enough meaning to replace symbols of the City provide viewers with imme- the felled Twin Towers. -

Batman: Year One by Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli Study Guide By

Graphic Novel Study Group Study Guides Batman: Year One By Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli Study guide by 1. In 1986, Miller and Mazzucchelli were charged with updating the classic character of Batman. DC Comics wanted to give the origin story “depth, complexity, a wider context.” Did Miller and Mazzucchelli succeed? 2. Why or why not? Give specific examples. 3. We meet Jimmy Gordon and Bruce Wayne at roughly the same moment in the novel. How are they portrayed differently, right from the beginning? Are these initial impressions in line with what we come to know about both characters later? 4. In both Jimmy and Bruce’s initial scenes, how are color and drawing style used to create an atmosphere, or to set them apart – their characters and their surroundings? Give a specific example for each. 5. Batman’s origin story is a familiar one to most readers. How do Miller and Mazzucchelli embroider the basic story? 6. What effect do their additions or subtractions have on your understanding of Bruce Wayne? 7. What are the major plots and subplots contained in the novel? 8. Where are the moments of high tension in the novel? 9. What happens directly before and after each one? How does the juxtaposition of low-tension and high-tension scenes or the repetition of high-tension scenes affect the pacing of the novel? 10. How have Jimmy Gordon and Bruce Wayne/Batman evolved over the course of the novel? How do we as readers understand this? Give specific examples. . -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

A Celebration of Superheroes Virtual Conference 2021 May 01-May 08 #Depaulheroes

1 A Celebration of Superheroes Virtual Conference 2021 May 01-May 08 #DePaulHeroes Conference organizer: Paul Booth ([email protected]) with Elise Fong and Rebecca Woods 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This has been a strange year, to be sure. My appreciation to everyone who has stuck with us throughout the trials and tribulations of the pandemic. The 2020 Celebration of Superheroes was postponed until 2021, and then went virtual – but throughout it all, over 90% of our speakers, both our keynotes, our featured speakers, and most of our vendors stuck with us. Thank you all so much! This conference couldn’t have happened without help from: • The College of Communication at DePaul University (especially Gina Christodoulou, Michael DeAngelis, Aaron Krupp, Lexa Murphy, and Lea Palmeno) • The University Research Council at DePaul University • The School of Cinematic Arts, The Latin American/Latino Studies Program, and the Center for Latino Research at DePaul University • My research assistants, Elise Fong and Rebecca Woods • Our Keynotes, Dr. Frederick Aldama and Sarah Kuhn (thank you!) • All our speakers… • And all of you! Conference book and swag We are selling our conference book and conference swag again this year! It’s all virtual, so check out our website popcultureconference.com to see how you can order. All proceeds from book sales benefit Global Girl Media, and all proceeds from swag benefit this year’s charity, Vigilant Love. DISCORD and Popcultureconference.com As a virtual conference, A Celebration of Superheroes is using Discord as our conference ‘hub’ and our website PopCultureConference.com as our presentation space. While live keynotes, featured speakers, and special events will take place on Zoom on May 01, Discord is where you will be able to continue the conversation spurred by a given event and our website is where you can find the panels. -

Efanzines.Com—Earl Kemp: E*

Vol. 7 No. 5 October 2008 -e*I*40- (Vol. 7 No. 5) October 2008, is published and © 2008 by Earl Kemp. All rights reserved. It is produced and distributed bi-monthly through efanzines.com by Bill Burns in an e-edition only. Happy Halloween! by Steve Stiles Contents—eI40—October 2008 Cover: “Happy Halloween!,” by Steve Stiles …Return to sender, address unknown….30 [eI letter column], by Earl Kemp The Fanzine Lounge, by Chris Garcia The J. Lloyd Eaton Collection, by Rob Latham and Melissa Conway Help Yourself to Eaton!, by Earl Kemp and Chris Garcia Eighty Pounds of Paper, by Earl Kemp It Just Took a Little Longer Than I Thought it Would, by Richard Lupoff SLODGE, by Jerry Murray Back cover: “Run, Baby, Run,” by Ditmar [Martin James Ditmar Jenssen] In the only love story he [Kilgore Trout] ever attempted, “Kiss Me Again,” he had written, “There is no way a beautiful woman can live up to what she looks like for any appreciable length of time.” The moral at the end of that story is this: Men are jerks. Women are psychotic. -- Kurt Vonnegut, Timequake THIS ISSUE OF eI is for the J. Lloyd Eaton Collection of Science Fiction, Fantasy, Horror, and Utopian Literature, housed in the Special Collections & Archives Department of the Tomás Rivera Library at UCRiverside. # As always, everything in this issue of eI beneath my byline is part of my in-progress rough-draft memoirs. As such, I would appreciate any corrections, revisions, extensions, anecdotes, photographs, jpegs, or what have you sent to me at [email protected] and thank you in advance for all your help. -

Volume 2 | Issue 1

The Reading Room a journal of special collections Volume 2, Issue 1 Volume 2, Issue 1 The Reading Room: A Journal of Special Collections is a scholarly journal committed to providing current research and relevant discussion of practices in a special collections library setting. The Reading Room seeks submissions from practitioners and students involved with working in special collections in museums, historical societies, corporate environments, public libraries and academic libraries. Topics may include exhibits, outreach, mentorship, donor relations, teaching, reference, technical and metadata skills, social media, “Lone Arrangers”, management and digital humanities. The journal features single-blind, peer-reviewed research articles and case studies related to all aspects of current special collections work. Journal credits Editors-in-Chief: Molly Poremski, Amy Vilz and Marie Elia Designer: Kristopher Miller Authors: Peterson Brink, Mary Ellen Ducey, Elizabeth Lorang, Erica Brown, Sarah M. Allison, Wendy Pflug, and Madeline Veitch. Cover photo: View of the Booth Family Center for Special Collections and The Paul F. Betz Reading Room at Georgetown University Library. Architects: Bowie Gridley, Construction: Manhattan Construction. Image courtesy of Bowie Gridley Architects and Georgetown University Library. University Archives University at Buffalo 420 Capen Hall Buffalo, NY, 14260 (716) 645-7750 [email protected] © 2016 The Reading Room, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York All rights reserved. ISSN: 2375-6101 Editors Note Dear Readers, Welcome to the third issue of Te Reading Room: A Journal of Special Collections! Our many thanks for your support and enthusiasm to provide an open access and scholarly forum for all those working in, or with, special collections.