Mind Moon Circle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

Explorers China Exploration and Research Society Volume 17 No

A NEWSLETTER TO INFORM AND ACKNOWLEDGE CERS’ FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS CHINA since 1986 EXPLORERS CHINA EXPLORATION AND RESEARCH SOCIETY VOLUME 17 NO. 2 SUMMER 2015 3 Last of the Pi Yao Minority People 30 Entering The Dinosaur’s Mouth 6 A Tang Dynasty Temple (circa 502 A.D.) 34 CERS in the Field 9 Avalanche! 35 News/Media & Lectures 12 Caught in Kathmandu 36 Thank You 15 Adventure to Dulongjiang Region: An Unspoiled place in Northwest Yunnan CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: 18 Blue Sky, White Peaks and Green Hills CERS and village cavers in Palawan 22 Shake-Down Cruise of HM Explorer 2 of the Philippines. A Yao elder lady. Earthquake news in Kathmandu. 26 Singing the Ocean Blues Suspension bridge across the Dulong Musings on fish and commitment while floating in the Sulu Sea River in Yunnan. CHINA EXPLORATION AND RESEARCH SOCIETY PAGE 1 A NEWSLETTER TO INFORM AND ACKNOWLEDGE CERS' FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS Founder / President WONG HOW MAN CHINA Directors: BARRY LAM, CERS Chairman Chairman, Quanta Computer, Taiwan EXPLORERS JAMES CHEN CHINA EXPLORATION AND RESEARCH SOCIETY Managing Director, Legacy Advisors Ltd. HUANG ZHENG YU VOLUME 17 NO.2 SUMMER 2015 Entrepreneur CHRISTABEL LEE President’s Message Managing Director, Toppan Vite Limited DAVID MONG isk management is institutionalized into all big Chairman, Shun Hing Education and Charity Fund businesses today, perhaps with exception of rogue traders among leading banks. In life, risk WELLINGTON YEE management extends from practical measures BILLY YUNG to philosophical ones, from having multiple Group Chairman, Shell Electric Holdings Ltd. Ralternatives of partners, insurance and bank accounts, Advisory Council: education and degrees, to Plan Bs & Cs for zillions of CYNTHIA D’ANJOU BROWN activities, to religious options for those who want to Philanthropy Adviser manage their afterlife, just in case there is an afterlife. -

Jy Din Shakya , a Biography

VENERABLE MASTER JY DIN SHAKYA , A BIOGRAPHY FORWARD BY REV . F A DAO SHAKYA , OHY The following story is the translation from the Chinese of a biography of VM Jy Din -- the Master responsible for the establishment of our Zen Buddhist Order of Hsu Yun. The article is straight journalism, perhaps a bit "dry" in comparison to some of the other Zen essays we are accustomed to encountering. The story of the story, however, is one of convergence, patience and luck -- if we consider “luck” to be the melding of opportunity and action. I have long wished to know more information about the founding master of our order and history of the Hsu Yun Temple in Honolulu. Like many of us, I have scoured books and websites galore for the merest mentions or tidbits of facts. Not being even a whit knowledgeable of Chinese language, any documentation in Master Jy Din's native language was beyond my grasp. I read what I could find -- and waited. I knew that some day I would stumble across that which I sought, if only I did not drive myself to distraction desiring it. Late in July of 2005, that which I had sought was unexpectedly delivered to me. By chance and good fortune, I received an e-mail from Barry Tse, in Singapore -- the continuance of a discussion we had originated on an internet "chat board." As the e-mail discussion continued, Barry mentioned an article he had found on a Chinese Buddhist website -- a biography of our direct Master Jy Din. He pointed out the website to me and I printed a copy of the article for my files. -

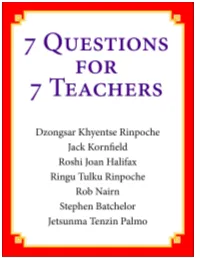

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

道不盡的思念 Endless Thoughts 沴

【海外來鴻】〈憶故人〉 道不盡的思念 Endless Thoughts 沴 by Lily Chang Angel Teng 南非 張莉華 撰文 鄧凱倢 英譯 編按雁本文為凱鴻之母親寫於凱鴻歸空三週年紀念日阻中文稿已刊登於2隹钃期阻歡 迎讀者前賢參閱阻今特刊登英文版(分兩次關以服務廣大英文讀者群阡 馞鶉上期馥馞To be continued 馥 Yuang Chia, as well as uncles and aun- ties from Buddha's Light Association 溫馨盛情的送別 heard of your accident, they have all The Sweet Farewell rushed their way to come pay their When we have finally found you homage to you. You were so fortunate after your accident, the Tzu Chi mem- that Venerable Hui Li had conducted bers have first volunteered to arrange the memorial service for you. Venerable your shrine at our house. They have Hui Li, is the South Africa Buddha's brought fresh flowers, fruits and things Light Association's first abbot (Fo for the setup. Later many more friends Guang Shan, Nan Hua Temple), he has from Tzu Chi, Buddha's Light dedicated his life to toil in propagating Association and I-Kuan Tao had came Buddhism in Africa, highly respected as to recite the holy scriptures for you. a Buddhism Venerable and loved by When Venerable Hui Fang, Venerable Africa people. 38 基礎雜誌胡臑9期 In order to recite “ The True Sutra in Taiwan. Transmit teachers, temple of Mi-Lei Buddha” perfectly in your owners, as well as Tao members from funeral, the I-Kuan Tao members had groups of Chi-Chu, Fa-Yi, Bao-kuang, countless rehearsals before the memori- Tian-Jen, and family friends have come al service. The youth Tao members, from all corners of Taiwan (Taipei, whom were responsible to guard your Taichung, Chiayi & Kaohsiung), they coffin on your day of service, had prac- have waited for your arrival at the ticed through out the nights too. -

“Zen Has No Morals!” - the Latent Potential for Corruption and Abuse in Zen Buddhism, As Exemplified by Two Recent Cases

“Zen Has No Morals!” - The Latent Potential for Corruption and Abuse in Zen Buddhism, as Exemplified by Two Recent Cases by Christopher Hamacher Paper presented on 7 July 2012 at the International Cultic Studies Association's annual conference in Montreal, Canada. Christopher Hamacher graduated in law from the Université de Montréal in 1994. He has practiced Zen Buddhism in Japan, America and Europe since 1999 and run his own Zen meditation group since 2006. He currently works as a legal translator in Munich, Germany. Christopher would like to thank Stuart Lachs, Kobutsu Malone and Katherine Masis for their help in writing this paper. 1 “Accusations, slander, attributions of guilt, alleged misconduct, even threats and persecution will not disturb [the Zen Master] in his practice. Defending himself would mean participating again in a dualistic game that he has moved beyond.” - Dr. Klaus Zernickow1 “It is unfair to conclude that my silence implies that I must be what the letters say I am. Indeed, in Japan, to protest too much against an accusation is considered a sign of guilt.” - Eido T. Shimano2 1. INTRODUCTION Zen Buddhism was long considered by many practitioners to be immune from the scandals that occasionally affect other religious sects. Zen’s iconoclastic approach, based solely on the individual’s own meditation experience, was seen as a healthy counterpoint to the more theistic and moralistic world-views, whose leading proponents often privately flouted the very moral codes that they preached. The unspoken assumption in Zen has always been that the meditation alone naturally freed the accomplished practitioner from life's moral quandaries, without the need for rigid rules of conduct imposed from above. -

Iabhonoree of the Year 1999 Introduction Grand Master Dr. Hsing

IABHonoree of the Year1 999 For a life-time of exceptional contributions to the advancement of study and education, practice and propagation of Buddhism through devout and dedicated identification with the highest ideals of leading humanity to harmony, peace, and enlightenment, and through the establishment of a worldwide network of Temples, Centers ofHigher Leaming and Monastic and Lay Institutions for the achievement of such ideals, the InternationalAcademy of Buddhism of Hsi Lai University, Los Angeles County, California, USA recognizes Venerable Grand Master Dr. Hsing Yun as Honoree of the Year 1999 at the First International Conference on Humanistic Buddhism on December 16, 1999. Grand Master Dr. Hsing Yun Introduction A major step taken by the University in promoting the dissemination of Buddhism with special reference to Grand Master Hsing Yun' s concepts and interpretation of Humanistic Buddhism was the creation of the International Academy ofBuddhism (IAB) on January 1, 1999. Itwas organized as an integral part of the University and complements the academic study of Buddhism in all its traditions and comparative religious studies of the University's Department of Religious Studies. Its operational plans for the year 1999 included the organization of the First International Conference on Humanistic Buddhism; the preparation of the Inaugural Volume of the Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism (HLnIB); the grant of fellowship to research scholar; and the recognition of a Buddhist scholar of exceptional eminence as the Honoree of the Year. It is with justifiable pride and pleasure that I announce the full accomplishment of the IAB Plan within the specifiedtime limits. The First International Conference on Humanistic Buddhism proceeded smoothly and successfully towards a fulfilling conclusion. -

On the Buddhist Roots of Contemporary Non-Religious Mindfulness Practice: Moving Beyond Sectarian and Essentialist Approaches 1

On the Buddhist roots of contemporary non-religious mindfulness practice: Moving beyond sectarian and essentialist approaches 1 VILLE HUSGAFVEL University of Helsinki Abstract Mindfulness-based practice methods are entering the Western cultural mainstream as institutionalised approaches in healthcare, educa- tion, and other public spheres. The Buddhist roots of Mindfulness- Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and comparable mindfulness-based programmes are widely acknowledged, together with the view of their religious and ideological neutrality. However, the cultural and historical roots of these contemporary approaches have received relatively little attention in the study of religion, and the discussion has been centred on Theravāda Buddhist viewpoints or essentialist presentations of ‘classical Buddhism’. In the light of historical and textual analysis it seems unfounded to hold Theravāda tradition as the original context or as some authoritative expression of Buddhist mindfulness, and there are no grounds for holding it as the exclusive Buddhist source of the MBSR programme either. Rather, one-sided Theravāda-based presentations give a limited and oversimplified pic- ture of Buddhist doctrine and practice, and also distort comparisons with contemporary non-religious forms of mindfulness practice. To move beyond the sectarian and essentialist approaches closely related to the ‘world religions paradigm’ in the study of religion, the discus- sion would benefit from a lineage-based approach, where possible historical continuities and phenomenological -

IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP a COMMENT on FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall

Soto Zen Buddhism in Australia June 2016, Issue 64 IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP A COMMENT ON FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall COMMITTEE NEWS MIRACLE OF TOSHOJI ONE BRIGHT PEARL Shona Innes Ekai Korematsu Osho Katrina Woodland VALE ZENKEI BLANCHE HARTMAN A MAGIC PLACE POEMS Shudo Hannah Forsyth Toshi Hirano Dan Carter, Andrew Holborn CULTIVATING FAITH RETREAT REFLEXION SOTO KITCHEN Ekai Korematsu Osho Peter Brammer Annie Bolitho CULTIVATING FAITH Cover calligraphy by Jinesh Wilmot 1 MYOJU IS A PUBLICATION OF JIKISHOAN ZEN BUDDHIST COMMUNITY INC Editorial Myoju Welcome to the Winter Solstice issue of Myoju, the first Editor: Ekai Korematsu of several issues with the theme Cultivating Faith. The Publications Committee: Hannah Forsyth, Christine cover image is calligraphy of enso with the character Faith Maingard, Katherine Yeo, Robin Laurie, Azhar Abidi inside it. The very first edition of Myoju in Spring 2000 had Myoju Coordinator: Robin Laurie an enso on the cover with a drawing of Ekai Osho in his Production: Darren Chaitman samu clothes making seating for the zendo in his garage. Website Manager: Lee-Anne Armitage An action based in great faith. IBS Teaching Schedule: Hannah Forsyth / Shona Innes Faith is a complex issue. It’s attached to phrases like ‘blind Jikishoan Calendar of Events: Shona Innes faith,’ which seem to trail a sense of mindless following and Contributors: Ekai Korematsu Osho, Shudo Hannah obedience. Forsyth, Katherine Yeo, Shona Innes, John Hickey, Karen Threlfall, Toshi Hirano, Peter Brammer, Katrina In that very first issue the meaning of Jikishoan is spelt out: Woodland, Andrew Holborn, Dan Carter and Annie jiki-direct, sho-realization an-hut: direct realisation hut. -

Summer 2012 Primary Point in THIS ISSUE 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A

Primary 7PMVNFt/VNCFSt4VNNFSP int 2] residential training CO-GUIDING TEACHERS: ZEN MAS- TER BON HAENG (MARK HOUGH- TON), NANCY HEDGPETH JDPSN LIVE AND PRACTICE AT THE KUSZ INTERNATIONAL HEAD TEMPLE IN A SUPPORTIVE COM- MUNITY OF DEDICATED ZEN STUDENTS. DAILY MEDITATION PRACTICE, INTERVIEWS WITH 2012 Summer kyol che GUIDING AND VISITING TEACH- KYOL CHE IS A TIME TO INVESTIGATE YOUR LIFE CLOSELY. HELD AT ERS, DHARMA TALKS, MONTHLY $ $%"#!%#$"().5*9:.865 WEEKEND RETREATS, SUM- *.5/;3> ;/ ).5*9:.8#6.5/>*5/;3> MER AND WINTER INTENSIVES, ;->"61:4*5 #;3> *5-15,"06-.9 #2;3> AND NORTH AMERICA SANGHA ;/ WEEKENDS. LOCATED ON 50 PZC Guest Stay Program - designed to allow ACRES OF FORESTED GROUNDS. folks to stay in the Zen Center and experience com- munity life for a short period of time, without the retreat rentals rigorous schedule of a retreat. for visiting groups 76;5-86*-,;4+.83*5-81 @ @-18.,:68786<1-.5,.?.568/@===786<1-.5,.?.568/ PRIMARY POINT Summer 2012 Primary Point IN THIS ISSUE 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Buddhadharma Telephone 401/658-1476 Zen Master Man Gong ................................................................4 www.kwanumzen.org [email protected] Buddha’s Birthday 2002 online archives: Zen Master Wu Bong ...................................................................5 www.kwanumzen.org/teachers-and-teaching/ primary-point/ “I Want!” Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonpro!t religious A kong-an interview with Zen Master Wu Kwang .........................6 corporation. "e founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the !rst Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. -

BLIA World Headquarters December 2018 ~ January 2019 Bulletin Work

BLIA World Headquarters December 2018 ~ January 2019 Bulletin Work Report 【I】 Veggie Plan A Results so far: up till November 28, 2018, a total of 86 countries and regions with 50,150 people responding to the petition. Below is the top ten country/region with the most registrants: No. of No. of Country/Region Country/Region Registrants Registrants 1 Taiwan 16,974 6 New Zealand 2,513 2 Hong Kong 13,783 7 Malaysia 1,152 3 Brazil 5,411 8 China 810 4 Canada 3,478 9 Australia 625 5 U.S.A. 2,713 10 South Africa 364 By September 1, 17,184 people responded and by November 28, 50,150 people signed up, with a 291.84% growth rate. Chapters are to continue in their efforts to promote the petition for practicing vegetarianism. Motion Discussion 【Motion 1】 Proposal: To encourage BLIA chapters worldwide establish subchapters. Description: 1. In accordance with BLIA “Chapter Organization Guideline” the Article III on Membership, the 7th Clause, “Members of the Association are divided into the following two categories: 1. Group Members, 2. Subchapter Member.” 2. In order to strengthen chapter organization, BLIA chapters worldwide that have not yet established subchapters should do so for developing talents and actualizing the ideal of “where there is sunshine, there is Buddha’s Light.” Procedure: 1. Please refer to Appx. 1 for procedure to establish subchapters. 2. When subchapter preparatory committees have matured, after evaluation and further approval, they can be certificated during the continent’s fellowship meeting or the chapter’s general meeting. 3. Tokens of trust for newly established as well as existing subchapters, flag and president sash should be applied from BLIA by the chapter (Appx.