It's All Very Simplistic This Buddhism Stuff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

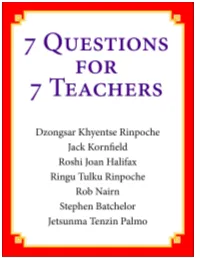

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

“Zen Has No Morals!” - the Latent Potential for Corruption and Abuse in Zen Buddhism, As Exemplified by Two Recent Cases

“Zen Has No Morals!” - The Latent Potential for Corruption and Abuse in Zen Buddhism, as Exemplified by Two Recent Cases by Christopher Hamacher Paper presented on 7 July 2012 at the International Cultic Studies Association's annual conference in Montreal, Canada. Christopher Hamacher graduated in law from the Université de Montréal in 1994. He has practiced Zen Buddhism in Japan, America and Europe since 1999 and run his own Zen meditation group since 2006. He currently works as a legal translator in Munich, Germany. Christopher would like to thank Stuart Lachs, Kobutsu Malone and Katherine Masis for their help in writing this paper. 1 “Accusations, slander, attributions of guilt, alleged misconduct, even threats and persecution will not disturb [the Zen Master] in his practice. Defending himself would mean participating again in a dualistic game that he has moved beyond.” - Dr. Klaus Zernickow1 “It is unfair to conclude that my silence implies that I must be what the letters say I am. Indeed, in Japan, to protest too much against an accusation is considered a sign of guilt.” - Eido T. Shimano2 1. INTRODUCTION Zen Buddhism was long considered by many practitioners to be immune from the scandals that occasionally affect other religious sects. Zen’s iconoclastic approach, based solely on the individual’s own meditation experience, was seen as a healthy counterpoint to the more theistic and moralistic world-views, whose leading proponents often privately flouted the very moral codes that they preached. The unspoken assumption in Zen has always been that the meditation alone naturally freed the accomplished practitioner from life's moral quandaries, without the need for rigid rules of conduct imposed from above. -

On the Buddhist Roots of Contemporary Non-Religious Mindfulness Practice: Moving Beyond Sectarian and Essentialist Approaches 1

On the Buddhist roots of contemporary non-religious mindfulness practice: Moving beyond sectarian and essentialist approaches 1 VILLE HUSGAFVEL University of Helsinki Abstract Mindfulness-based practice methods are entering the Western cultural mainstream as institutionalised approaches in healthcare, educa- tion, and other public spheres. The Buddhist roots of Mindfulness- Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and comparable mindfulness-based programmes are widely acknowledged, together with the view of their religious and ideological neutrality. However, the cultural and historical roots of these contemporary approaches have received relatively little attention in the study of religion, and the discussion has been centred on Theravāda Buddhist viewpoints or essentialist presentations of ‘classical Buddhism’. In the light of historical and textual analysis it seems unfounded to hold Theravāda tradition as the original context or as some authoritative expression of Buddhist mindfulness, and there are no grounds for holding it as the exclusive Buddhist source of the MBSR programme either. Rather, one-sided Theravāda-based presentations give a limited and oversimplified pic- ture of Buddhist doctrine and practice, and also distort comparisons with contemporary non-religious forms of mindfulness practice. To move beyond the sectarian and essentialist approaches closely related to the ‘world religions paradigm’ in the study of religion, the discus- sion would benefit from a lineage-based approach, where possible historical continuities and phenomenological -

IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP a COMMENT on FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall

Soto Zen Buddhism in Australia June 2016, Issue 64 IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP A COMMENT ON FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall COMMITTEE NEWS MIRACLE OF TOSHOJI ONE BRIGHT PEARL Shona Innes Ekai Korematsu Osho Katrina Woodland VALE ZENKEI BLANCHE HARTMAN A MAGIC PLACE POEMS Shudo Hannah Forsyth Toshi Hirano Dan Carter, Andrew Holborn CULTIVATING FAITH RETREAT REFLEXION SOTO KITCHEN Ekai Korematsu Osho Peter Brammer Annie Bolitho CULTIVATING FAITH Cover calligraphy by Jinesh Wilmot 1 MYOJU IS A PUBLICATION OF JIKISHOAN ZEN BUDDHIST COMMUNITY INC Editorial Myoju Welcome to the Winter Solstice issue of Myoju, the first Editor: Ekai Korematsu of several issues with the theme Cultivating Faith. The Publications Committee: Hannah Forsyth, Christine cover image is calligraphy of enso with the character Faith Maingard, Katherine Yeo, Robin Laurie, Azhar Abidi inside it. The very first edition of Myoju in Spring 2000 had Myoju Coordinator: Robin Laurie an enso on the cover with a drawing of Ekai Osho in his Production: Darren Chaitman samu clothes making seating for the zendo in his garage. Website Manager: Lee-Anne Armitage An action based in great faith. IBS Teaching Schedule: Hannah Forsyth / Shona Innes Faith is a complex issue. It’s attached to phrases like ‘blind Jikishoan Calendar of Events: Shona Innes faith,’ which seem to trail a sense of mindless following and Contributors: Ekai Korematsu Osho, Shudo Hannah obedience. Forsyth, Katherine Yeo, Shona Innes, John Hickey, Karen Threlfall, Toshi Hirano, Peter Brammer, Katrina In that very first issue the meaning of Jikishoan is spelt out: Woodland, Andrew Holborn, Dan Carter and Annie jiki-direct, sho-realization an-hut: direct realisation hut. -

Summer 2012 Primary Point in THIS ISSUE 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A

Primary 7PMVNFt/VNCFSt4VNNFSP int 2] residential training CO-GUIDING TEACHERS: ZEN MAS- TER BON HAENG (MARK HOUGH- TON), NANCY HEDGPETH JDPSN LIVE AND PRACTICE AT THE KUSZ INTERNATIONAL HEAD TEMPLE IN A SUPPORTIVE COM- MUNITY OF DEDICATED ZEN STUDENTS. DAILY MEDITATION PRACTICE, INTERVIEWS WITH 2012 Summer kyol che GUIDING AND VISITING TEACH- KYOL CHE IS A TIME TO INVESTIGATE YOUR LIFE CLOSELY. HELD AT ERS, DHARMA TALKS, MONTHLY $ $%"#!%#$"().5*9:.865 WEEKEND RETREATS, SUM- *.5/;3> ;/ ).5*9:.8#6.5/>*5/;3> MER AND WINTER INTENSIVES, ;->"61:4*5 #;3> *5-15,"06-.9 #2;3> AND NORTH AMERICA SANGHA ;/ WEEKENDS. LOCATED ON 50 PZC Guest Stay Program - designed to allow ACRES OF FORESTED GROUNDS. folks to stay in the Zen Center and experience com- munity life for a short period of time, without the retreat rentals rigorous schedule of a retreat. for visiting groups 76;5-86*-,;4+.83*5-81 @ @-18.,:68786<1-.5,.?.568/@===786<1-.5,.?.568/ PRIMARY POINT Summer 2012 Primary Point IN THIS ISSUE 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Buddhadharma Telephone 401/658-1476 Zen Master Man Gong ................................................................4 www.kwanumzen.org [email protected] Buddha’s Birthday 2002 online archives: Zen Master Wu Bong ...................................................................5 www.kwanumzen.org/teachers-and-teaching/ primary-point/ “I Want!” Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonpro!t religious A kong-an interview with Zen Master Wu Kwang .........................6 corporation. "e founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the !rst Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. -

P Int Primary Volume 33 • Number 1 • Spring 2016

PRIMARY POINT® Kwan Um School of Zen 99 Pound Rd Cumberland, RI 02864-2726 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Primary Primary P int P Volume 33 • Number 1 • Spring 2016 2016 Spring • 1 Number • 33 Volume Summer Kyol Che 2016 July 9 - August 5 Silent retreats including sitting, chanting, walking and bowing practice. Dharma talks and Kong An interviews. Retreats Kyol Che Visit, practice or live at the head YMJJ 401.658.1464 Temple of Americas Kwan Um One Day www.providencezen.com School of Zen. Solo Retreats [email protected] Guest Stays Residential Training Rentals PRIMARY POINT Spring 2016 Primary Point 99 Pound Road IN THIS ISSUE Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 The Moment I Became a Monk www.kwanumzen.org Zen Master Dae Jin .....................................................................4 online archives: Visit kwanumzen.org to learn more, peruse back Biography of Zen Master Dae Jin ............................................5 issues and connect with our sangha. Funeral Ceremony and Cremation Rites for Zen Master Dae Jin ...................................................................5 Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit reli- gious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Bodhisattva Way Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Zen Master Dae Jin .....................................................................6 Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um The True Spirit of Zen sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He Zen Master Dae Jin gave transmission to Zen Masters, and inka (teaching author- .....................................................................8 ity) to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sas (dharma masters). -

Introducing Buddhism

BUDDHIST GROUP OF KENDAL (THERAVA¯ DA) extends its grateful thanks to members of the Group and to members of Keswick Buddhist Group, Keswick, England Ketumati Buddhist Viha¯ra, Oldham, England for bearing the cost of re-printing this booklet BUDDHIST GROUP OF KENDAL (THERAVA¯ DA) c/o FELLSIDE CENTRE LOW FELLSIDE KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 4NH ENGLAND BUDDHIST GROUP OF KENDAL (THERAVA¯ DA) INTRODUCING BUDDHISM Venerable Dr Balangoda A¯ nanda Maitreya Maha¯na¯yaka Thera Abhidhaja Maharatthaguru Aggamaha¯ Pandita DLitt D Litt (1896-1998) ·· and Jayasili (Jacquetta Gomes BA DipLib MLS FRAS ALA) INTRODUCING BUDDHISM Contents What is Buddhism? ............................................................................. 2 The Four Noble Truths ....................................................................... 4 The Eightfold Path .............................................................................. 6 The History and the Disposition of Traditions ................................. 8 The Three Basic Facts of Existence ................................................... 10 Buddhist Meditation ........................................................................... 12 The Buddhist Teaching of Kamma and Rebirth ............................... 14 Summing Up ....................................................................................... 16 Buddhist Literature ............................................................................. 18 Glossary .............................................................................................. -

Entering the Sangha.Pub

Vermont Zen Center Entering the Sangha Members of the Vermont Zen Center, the Toronto Zen Centre, and the Casa Zen, in Santo Tomás, Costa Rica comprise our Buddhist community, or Sangha . Membership in the Zen Center is open to all people regardless of race, national origin, creed, sex or sexual orientation. This Zen Center is in the lineage of Roshi Philip Kapleau. It is not subsidized by any other organization, nor does it have an endowment. The Vermont Zen Center is a nonprofit, religious, tax-exempt 501(c)3 corporation maintained by contributions of members and friends. There is no staff other than the teacher, Roshi Graef. While attendance at most Center functions is restricted to members, non-members may join on occasion after checking with the Center. Members may attend private instruction about Zen practice, which is held once a month. Trial members are wel- come to attend group instruction. Dokusan (formal Zen instruction) is available for members who become students of Roshi. Anyone 18 and older (or younger with parental permission) may become a member of the Center through the following steps: • Attending an Introductory Workshop conducted by Roshi Sunyana Graef; • Completing a four-week trial membership period; • Requesting full membership and submitting a membership application; • Making a financial pledge to the Zen Center. The suggested minimum donation is $45 per month. However, no one is excluded from membership because of inability to pay. If our fees are an obstacle to your training at the Center, please let us know so that we can discuss alternatives. Your first membership pledge should be paid when you submit your application. -

IBC Newsletter

SambodhIBC Newsletter VOLUME I ISSUE 4 OCTOBER 2015 COUNCIL OF PatrONS SAMVAD – GLOBAL HINDU-BUDDHIST INITIATIVE ON His Holiness Somdet Phra Nyanasamvara CONFLICT AVOIDANCE AND ENVIRONMENT CONSCIOUSNESS Sangharaja Supreme Patriarch, Thailand His Holiness Phra Achan Maha Phong Sangharaja Acting President PM Modi hails the teachings Lao Buddhist Fellowship Organisation, Laos His Holiness Thich Pho Tue Supreme Patriarch National Vietnam Buddhist Sangha, Vietnam of the Buddha His Holiness Samdech Preah Agga Maha Sangharajadhikari Te Vong ver 21 countries represented by lead- The Great Supreme Patriarch of Cambodia ing scholars, teachers of spirituality His Holiness Dr Bhaddanta Kumarabhivamsa O Sangharaja and religion, venerable bhikkus, political Chairman leaders and former heads of state, con- State Sangha Mahanayak Committee, Myanmar His Holiness Aggamaha Pandita Davuldena verged for the ‘Samvad – Global Hindu- Gnanissara Mahanayaka Thero Buddhist Initiative on Conflict Avoidance Supreme Prelate and Environmental Consciousness’ in New Amarapura Mahanikaya, Sri Lanka His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama Tenzing Gyatso Delhi in early September. Inaugurating the His Holiness Jinje-Beopwon conference, Prime Minister of India, Na- th 13 Supreme Patriarch rendra Modi, emphasised that teachings Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, South Korea His Eminence Khamba Lama Damba Ayushev in Buddhism and Hinduism can provide Supreme Head of Russian Buddhists, answers to many of the world’s problems, Buryat Republic, Russian Federation especially those related with conflict and His Holiness Sanghanayaka Sudhananda Mahathero President, Bangladesh Bouddha Kristi Prachar environment. “The message and teachings Sangha and Lord Abbot, Dharmarajika Buddhist of Gautama Buddha,” he said, “resonate Monastery, Bangladesh loudly and clearly with the major themes His Eminence Rev. -

Spring 2014 Summer Kyol Che 2014 July 5 - August 1 at Providence Zen Center Teaching Schedule TBA

Primary VolumeP 31 • Number 1 int• Spring 2014 Summer Kyol Che 2014 July 5 - August 1 at Providence Zen Center Teaching Schedule TBA Please Join Us And Awaken Your Insight! See your guiding teacher for information on obtaining a scholarship 2] [email protected] - www.providencezen.org - 401-658-1464 PRIMARY POINT Spring 2014 Primary Point 99 Pound Road, IN THIS ISSUE Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 Perceive World www.kwanumzen.org Empty Is Clear [email protected] Zen Master Su Bong ....................................................................4 online archives: After the Body, Where Will It Go? www.kwanumzen.org/teachers-and-teaching/ Pure Land primary-point Zen Master Dae Kwan .................................................................5 Remembering Zen Master Seung Sahn Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit reli- gious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Zen Master Hae Kwang ...............................................................6 Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching This sI the Bodhi Tree in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um Zen Master Wu Kwang ................................................................8 sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He gave transmission to Zen Masters, and inka (teaching author- Sitting in a Cave . in New York City ity) to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sas (dharma masters). Nancy Hathaway .......................................................................11 The Kwan Um School of Zen supports the worldwide teaching schedule of the Zen Masters and Ji Do Poep Sas, assists the Morning Bell Reverberates Throughout the Universe: member Zen centers and groups in their growth, issues publi- Notes on a Residency at the London Zen Centre cations on contemporary Zen practice, and supports dialogue Pedro Dinis Correia ...................................................................12 among religions. -

The Generation Dharma Teachers

THE GENERATION X 2019 DHARMA TEACHERS CONFERENCE June 12-16, 2019 Great Vow Zen Monastery TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Message from the Planning Committee 2 GenX 2019 Schedule 3 Conference Schedule Day-by-Day 4 Program Details: The Ethical Transformation, Panel on Integrity 7 and Enlightenment About Great Vow Zen Monastery 8 Great Vow Zen Monastery Map 9 Participants List 10 Notes 13 Thank You 17 1 GENX2019 WELCOME Welcome to the 5th Gen X Teachers gathering. What an amazing achievement. We have been meeting as an inter-lineage community, convening different teachers from all different forms of Buddhism, every 2 years since 2011. This community is unique in that it changes every time we meet, it’s never the exact group of teachers coming together. Every one of you helps to create a space for practice on and off the cushions, reflection, dialogue, and networking at these gatherings. It’s an opportunity to drop our teacher roles and relate to each other as peers, friends and fellow dharma practitioners. We encourage people to intentionally reach out and connect with people from different lineages and take the opportunity to sit down for lunch or go for a walk with someone you don’t know. This is your gathering, if you just need time to be in the beautiful landscape that Great Vow is situated in, then please take that time. We hope that the gathering will nourish and inspire you. Thank you all for taking the time out of your busy lives to join us. Blessings from the 2019 Planning committee.