A Retrospective Snapshot of American Zen in 1973

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts. -

One Wedding and Two Funerals Founder's Day Ti

Volume 72 One Wedding and Two Funerals Number 8 This year the month of May marks the twentieth wedding May anniversary for Gary and me. But when I think back to our 2016 A.D. wedding, I can’t help thinking of it as a sad time for both of our 2559 B.E. mothers. Articles A week before our wedding after the May monthly memorial One Wedding and service at our temple, we were told by Gary’s mother that she Rev. Patti Nakai Two Funerals by needed to get to her brother Jiro’s place right away. She had Resident Minister Rev. Patti Nakai ..1 received word that her brother, who had long struggled with For more writings Founder’s Day Parkinson’s disease, had taken a turn for the worse and death was by Rev. Nakai, Ti Sarana by Bill visit her blog, Bohlman ............1 imminent. When we went to see Uncle Jiro, he was in bed and Taste of Chicago Editorial: A Warning alert and to me he didn’t look like someone near death, but rather Buddhism, at: and Apologies……2 tinyurl.com/chibud youthful with his thick black hair. A couple days later he passed Haiku Corner: At away. Hanamatsuri, On the evening before the wedding, usually couples have their Basho’s Message by Elaine Siegel .......5 wedding rehearsal and rehearsal dinner, but Gary and I, and all his This article Separation, relatives were at Uncle Jiro’s funeral, a solemn Konko-kyo continues Initiation and ceremony conducted by Rev. Alfred Tsuyuki from Los Angeles. -

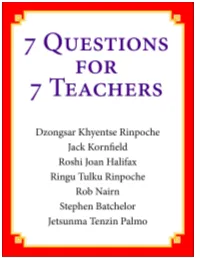

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

“Zen Has No Morals!” - the Latent Potential for Corruption and Abuse in Zen Buddhism, As Exemplified by Two Recent Cases

“Zen Has No Morals!” - The Latent Potential for Corruption and Abuse in Zen Buddhism, as Exemplified by Two Recent Cases by Christopher Hamacher Paper presented on 7 July 2012 at the International Cultic Studies Association's annual conference in Montreal, Canada. Christopher Hamacher graduated in law from the Université de Montréal in 1994. He has practiced Zen Buddhism in Japan, America and Europe since 1999 and run his own Zen meditation group since 2006. He currently works as a legal translator in Munich, Germany. Christopher would like to thank Stuart Lachs, Kobutsu Malone and Katherine Masis for their help in writing this paper. 1 “Accusations, slander, attributions of guilt, alleged misconduct, even threats and persecution will not disturb [the Zen Master] in his practice. Defending himself would mean participating again in a dualistic game that he has moved beyond.” - Dr. Klaus Zernickow1 “It is unfair to conclude that my silence implies that I must be what the letters say I am. Indeed, in Japan, to protest too much against an accusation is considered a sign of guilt.” - Eido T. Shimano2 1. INTRODUCTION Zen Buddhism was long considered by many practitioners to be immune from the scandals that occasionally affect other religious sects. Zen’s iconoclastic approach, based solely on the individual’s own meditation experience, was seen as a healthy counterpoint to the more theistic and moralistic world-views, whose leading proponents often privately flouted the very moral codes that they preached. The unspoken assumption in Zen has always been that the meditation alone naturally freed the accomplished practitioner from life's moral quandaries, without the need for rigid rules of conduct imposed from above. -

On the Buddhist Roots of Contemporary Non-Religious Mindfulness Practice: Moving Beyond Sectarian and Essentialist Approaches 1

On the Buddhist roots of contemporary non-religious mindfulness practice: Moving beyond sectarian and essentialist approaches 1 VILLE HUSGAFVEL University of Helsinki Abstract Mindfulness-based practice methods are entering the Western cultural mainstream as institutionalised approaches in healthcare, educa- tion, and other public spheres. The Buddhist roots of Mindfulness- Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and comparable mindfulness-based programmes are widely acknowledged, together with the view of their religious and ideological neutrality. However, the cultural and historical roots of these contemporary approaches have received relatively little attention in the study of religion, and the discussion has been centred on Theravāda Buddhist viewpoints or essentialist presentations of ‘classical Buddhism’. In the light of historical and textual analysis it seems unfounded to hold Theravāda tradition as the original context or as some authoritative expression of Buddhist mindfulness, and there are no grounds for holding it as the exclusive Buddhist source of the MBSR programme either. Rather, one-sided Theravāda-based presentations give a limited and oversimplified pic- ture of Buddhist doctrine and practice, and also distort comparisons with contemporary non-religious forms of mindfulness practice. To move beyond the sectarian and essentialist approaches closely related to the ‘world religions paradigm’ in the study of religion, the discus- sion would benefit from a lineage-based approach, where possible historical continuities and phenomenological -

IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP a COMMENT on FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall

Soto Zen Buddhism in Australia June 2016, Issue 64 IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP A COMMENT ON FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall COMMITTEE NEWS MIRACLE OF TOSHOJI ONE BRIGHT PEARL Shona Innes Ekai Korematsu Osho Katrina Woodland VALE ZENKEI BLANCHE HARTMAN A MAGIC PLACE POEMS Shudo Hannah Forsyth Toshi Hirano Dan Carter, Andrew Holborn CULTIVATING FAITH RETREAT REFLEXION SOTO KITCHEN Ekai Korematsu Osho Peter Brammer Annie Bolitho CULTIVATING FAITH Cover calligraphy by Jinesh Wilmot 1 MYOJU IS A PUBLICATION OF JIKISHOAN ZEN BUDDHIST COMMUNITY INC Editorial Myoju Welcome to the Winter Solstice issue of Myoju, the first Editor: Ekai Korematsu of several issues with the theme Cultivating Faith. The Publications Committee: Hannah Forsyth, Christine cover image is calligraphy of enso with the character Faith Maingard, Katherine Yeo, Robin Laurie, Azhar Abidi inside it. The very first edition of Myoju in Spring 2000 had Myoju Coordinator: Robin Laurie an enso on the cover with a drawing of Ekai Osho in his Production: Darren Chaitman samu clothes making seating for the zendo in his garage. Website Manager: Lee-Anne Armitage An action based in great faith. IBS Teaching Schedule: Hannah Forsyth / Shona Innes Faith is a complex issue. It’s attached to phrases like ‘blind Jikishoan Calendar of Events: Shona Innes faith,’ which seem to trail a sense of mindless following and Contributors: Ekai Korematsu Osho, Shudo Hannah obedience. Forsyth, Katherine Yeo, Shona Innes, John Hickey, Karen Threlfall, Toshi Hirano, Peter Brammer, Katrina In that very first issue the meaning of Jikishoan is spelt out: Woodland, Andrew Holborn, Dan Carter and Annie jiki-direct, sho-realization an-hut: direct realisation hut. -

Summer 2012 Primary Point in THIS ISSUE 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A

Primary 7PMVNFt/VNCFSt4VNNFSP int 2] residential training CO-GUIDING TEACHERS: ZEN MAS- TER BON HAENG (MARK HOUGH- TON), NANCY HEDGPETH JDPSN LIVE AND PRACTICE AT THE KUSZ INTERNATIONAL HEAD TEMPLE IN A SUPPORTIVE COM- MUNITY OF DEDICATED ZEN STUDENTS. DAILY MEDITATION PRACTICE, INTERVIEWS WITH 2012 Summer kyol che GUIDING AND VISITING TEACH- KYOL CHE IS A TIME TO INVESTIGATE YOUR LIFE CLOSELY. HELD AT ERS, DHARMA TALKS, MONTHLY $ $%"#!%#$"().5*9:.865 WEEKEND RETREATS, SUM- *.5/;3> ;/ ).5*9:.8#6.5/>*5/;3> MER AND WINTER INTENSIVES, ;->"61:4*5 #;3> *5-15,"06-.9 #2;3> AND NORTH AMERICA SANGHA ;/ WEEKENDS. LOCATED ON 50 PZC Guest Stay Program - designed to allow ACRES OF FORESTED GROUNDS. folks to stay in the Zen Center and experience com- munity life for a short period of time, without the retreat rentals rigorous schedule of a retreat. for visiting groups 76;5-86*-,;4+.83*5-81 @ @-18.,:68786<1-.5,.?.568/@===786<1-.5,.?.568/ PRIMARY POINT Summer 2012 Primary Point IN THIS ISSUE 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Buddhadharma Telephone 401/658-1476 Zen Master Man Gong ................................................................4 www.kwanumzen.org [email protected] Buddha’s Birthday 2002 online archives: Zen Master Wu Bong ...................................................................5 www.kwanumzen.org/teachers-and-teaching/ primary-point/ “I Want!” Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonpro!t religious A kong-an interview with Zen Master Wu Kwang .........................6 corporation. "e founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the !rst Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. -

THE BUDDHA and WHAT HE TAUGHT (Part One in a Four‐Part Series on Buddhism in North America)

STATEMENT DB‐565‐1 THE BUDDHA AND WHAT HE TAUGHT (Part One in a Four‐Part Series on Buddhism in North America) by J. Isamu Yamamoto Summary In recent years Asian immigration to North America has risen dramatically, and with these people has come their Buddhist faith. At the same time many non‐ Asian North Americans have adopted Buddhism as their religion. In order to present the gospel effectively to both of these groups it is clear that Christians need to have a fundamental understanding of Buddhism. Siddhartha Gautama lived over twenty‐five centuries ago, but as the Buddha his life and teachings still inspire the faith of millions of people throughout Asia. The Buddha rejected the religions of his day in India and taught a new approach to religion — a life not of luxury and pleasure nor of extreme asceticism, but the Middle Way. Even in the West many find Buddhism appealing because its principles seem sensible and compassionate. I must confess: I love peaches. The juicy texture, the sweet fragrance, the luscious taste — I love everything about peaches. I always have. As a youngster I grew up in San Jose, California. During the fifties, San Jose was a small town nestled in the Santa Clara Valley. At that time it was a valley full of fruit orchards. Today it is known as ʺSilicon Valley,ʺ and most of the orchards are gone. Forty years ago I could wander through orchards and enjoy cherries, apricots, and, of course, peaches. One day I was with my dad, who worked in the orchards as a field hand. -

The Interconnectedness of Well-Being Zen Buddhist Teachings on Holistic Sustainability

The Interconnectedness of Well-Being Zen Buddhist Teachings on Holistic Sustainability Tess Edmonds AHS Capstone Project, Spring 2011 Disciplinary Deliverable P a g e | 2 I swear the earth shall surely be complete to him or her who shall be complete, The earth remains jagged and broken only to him or her who remains jagged and broken I swear, there is no greatness of power that does not emulate those of the earth, There can be no theory of any account unless it corroborate the theory of the earth, No politics, song, religion, behavior, or what not, is of account unless it compare with the amplitude of the earth, Unless it face the exactness, vitality, impartiality, rectitude of the earth. I swear I begin to see love with sweeter spasms than that which responds love, It is that which contains itself, which never invites and never refuses. I swear, I begin to see little or nothing in audible words, All merges toward the presentation of the unspoken meanings of the earth, Toward him who sings the songs of the body and of the truths of the earth, Toward him who makes the dictionaries of words that print cannot touch. -Walt Whitman P a g e | 3 A PERSONAL NOTE OF INTRODUCTION This project began with a personal journey of exploration, experience, and thinking about how to bring together areas I have increasingly sensed are interrelated. As far back as I can remember, I have always had a deep-rooted love for Nature – a quiet reverence for the mountains and rivers, animals and plants with which we share this planet. -

New Religions in Global Perspective

New Religions in Global Perspective New Religions in Global Perspective is a fresh in-depth account of new religious movements, and of new forms of spirituality from a global vantage point. Ranging from North America and Europe to Japan, Latin America, South Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, this book provides students with a complete introduction to NRMs such as Falun Gong, Aum Shinrikyo, the Brahma Kumaris movement, the Ikhwan or Muslim Brotherhood, Sufism, the Engaged Buddhist and Neo-Hindu movements, Messianic Judaism, and African diaspora movements including Rastafarianism. Peter Clarke explores the innovative character of new religious movements, charting their cultural significance and global impact, and how various religious traditions are shaping, rather than displacing, each other’s understanding of notions such as transcendence and faith, good and evil, of the meaning, purpose and function of religion, and of religious belonging. In addition to exploring the responses of governments, churches, the media and general public to new religious movements, Clarke examines the reactions to older, increasingly influential religions, such as Buddhism and Islam, in new geographical and cultural contexts. Taking into account the degree of continuity between old and new religions, each chapter contains not only an account of the rise of the NRMs and new forms of spirituality in a particular region, but also an overview of change in the regions’ mainstream religions. Peter Clarke is Professor Emeritus of the History and Sociology of Religion at King’s College, University of London, and a professorial member of the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford. Among his publications are (with Peter Byrne) Religion Defined and Explained (1993) and Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective (ed.) (2000).