No One Is Alone: Responsibility, Consequences, and Family in Into the Woods Jennifer White

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Western Sydney

Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Creative Arts UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY School of Communication Arts Institute for Culture and Society Principal Supervisor: Dr. Maria AnGel Co-supervisor: Prof. Hart Cohen 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has taken me seven years to complete and I would like to sincerely thank all the people who have, in one way or another, helped to make it possible. Despite all the difficulty I encountered, I found diverse kinds of support along the way, from friends, colleagues, family, experts and organisations, who have helped me persist with and conclude this project. A special thanks to Mestre Roxinho, Chiara Ridolfi, Elisabeth Pickering and 30 young refugees at Cabramatta High School for agreeing to be filmed so closely for such a long period of time. This was an expansive and difficult exercise in trust. I admire them for that. I want to acknowledge the generosity and expertise of the original academic supervisors Cristina Rocha, Hart Cohen, Megan Watkins, who have contributed to this project. Greg Nobel for having mediated the difficult moments along the way. I specially want to thank Dr. Maria Angel for having come onboard this project as my Principal Supervisor in the last year of my candidature. I am also very thankful for the support I received from volunteers and tutors who worked in the implementation of the project in 2010, and for the film equipment provided by the University of Western Sydney’s School of Communication Arts and the Institute for Culture and Society. The film component of this DCA was only possible because of this support. -

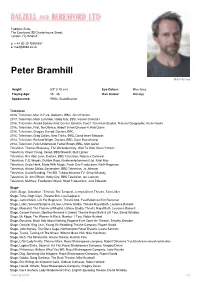

Peter Bramhill Matt Hussey

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Peter Bramhill Matt Hussey Height: 5'9" (175 cm) Eye Colour: Blue-Grey Playing Age: 35 - 45 Hair Colour: Blond(e) Appearance: White, Scandinavian Television 2019, Television, Man In Park, Alabama, BBC, Jim O'Hanlon 2017, Television, Mark Lumsden, Holby City, BBC, Various Directors 2016, Television, Arnold Sommerfeld, Genius: Einstein, Fox21 Television Studios, National Geographic, Kevin Hooks 2016, Television, Pilot, No Offence, Abbott Vision Channel 4, Rob Quinn 2016, Television, Gregory Garrod, Doctors, BBC, 2015, Television, Greg Collins, New Tricks, BBC, David Innes-Edwards 2013, Television, Richard Wright, Doctors, BBC, Dave Beauchamp 2013, Television, Felix Underwood, Father Brown, BBC, Matt Carter Television, Thomas Blakeway, The Wickedest City, Wall To Wall, Diene Petterle Television, Oliver Young, Vexed, BBC/Greenlit, Matt Lipsey Television, Rev Able Lunn, Doctors, BBC Television, Rebecca Gatward Television, P.C. Woods, Dustbin Baby, Kindle entertainment Ltd, Juliet May Television, Uncle Hank, Made With Magic, Fresh One Productions, Keith Rogerson Television, Alistair Childs, Eastenders, BBC Television, Jo Johnson Television, David Standing, The Bill, Talkbackthames TV, Simon Massey Television, Dr Jim O'Brien, Holby City, BBC Television, Ian Jackson Television, Matthew, Footballers Wives, Shed Productions, Julie Edwards Stage 2020, Stage, Sebastian / Trinculo, The Tempest, Jermyn Street Theatre, Tom Littler Stage, -

1992-10 the Mystery of Edwin Drood.Pdf

ob Hill Would Like to Wish Everyone an Enjoyable Night at the Opera! Remember Nob Hill For Quick Meals from the Deli & Seafood and Delectable Desserts from our Bakery We're Open Daily 7 a.m. till 10 PROGRAM ADVERTISING RATES You Will Get Three Consecutive Shows For One Pricel For More Information Call: Gene Pincus at (408) 257-7951! West Valley Light Opera Presents Book, Music and Lyrics by Rupert Holmes THE MYSTERY Musical Arrangements through OF TAMS-WITMARK MUSIC LIBRARY EDWIN DROOD Director: KEVIN CORMIER Music Director: MYNDALL SHIVERS Choreographer: BRAD HANSHY Producer: ELIZABETH DALE Drood (The Mystery of Edwin Drood) is produced by arrangement with Tams-Witmark Music Library, Inc. 560 Lexington Ave. New York, NY 10022 Performance Dates: Gala Opening Sat. October 31 8:00pm Curtain Friday, November 6, 1],20,27, December 4 8:00pm Curtain Saturday, November 7,14,21,28, December 5 8:00pm Curtain Saturday Matinee, November 14 2:30pm Curtain Sunday Matinee, November 1,8, 15,22, 29 .2:30pm Curtain Thursday evening, December 3 8:00pm Curtain Theatre opens 1/2 hour Before Curtain West Valley Box Office, Saratoga Civic Theatre C/O Jean Hutchins 13777 Fruitvale Ave. 1411 Redmond Rd. Saratoga, CA San Jose, CA 95120 408-741-9508 408-268-3777 1 Hour Before Curtain PLEASE NOTE: By order of the City Council and the Fire Marshall, smoking, refreshments and recording or taking photographs during performances are not permitted. WHAT TO EXPECT IN THIS PERFORMANCE OF "DROOD" A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR Welcome and thank you for attending our production of "The Mystery of Edwin Drood". -

Schallplatten

1 Deutsche Musicalarchiv, Sammlung Baberg Schallplatten Titel: Zusatz zum Titel, (Interpr.:). - Signatur: Anzahl Materialart Bemerkung Ersch.-Jahr, Verlag Schallplatte Deutsches Musicalarchiv, Sammlung Hair: From the London Musical Production (Komp.: Galt Baberg MacDermot, Text: James Rado, Gerome Ragni, Interpret.: Vince PL 6052 1 Edward, Oliver tobias, Michael Fest, Peter Straker, Joanne White, etc.) - 1968, Hamburg, Polydor International GmbH Hair: Original Soundtrack Recording of Milos Forman´s Film Schallplatte Deutsches Musicalarchiv, Sammlung (Komp.: Galt MacDermot, Text: James Rado, Gerome Ragni, Baberg PL 6053/1-2 Interpret.: John Savage, Treat Williams, Beverly d´Angelo, Annie 1 Golden, Dorsey Wright, Don Dacus, Cheryl Barnes, Melba Moore). - 1979, Hamburg, RCA Schallplatten GmbH Hallelujah, Baby!: (Komp.: Jule Styne, Text: Betty Comden, Adolph Schallplatte Deutsches Musicalarchiv, Sammlung PL 6054 Green, Interpret.: Leslie Uggams, Robert Hook, Allen Case, etc.) - 1 Baberg 1967, USA, Columbia Records Schallplatte Deutsches Musicalarchiv, Sammlung Hello Dolly: Original motion picture sountrack album of Ernest Baberg Lehman´s production (Komp., Text: Jerry Herman, Interpret.: PL 6055 1 Barbara Streisand, Walter Matthau, Michael Crawford, Louis Armstrong, etc.) - 1969, Hamburg, PHONOGRAM GmbH Schallplatte Deutsches Musicalarchiv, Sammlung Camelot: How to Handle a Woman. If I Would Ever Leave You: Baberg PL 6056 (Komp.: Frederick Loewe, Text: Alan Jay Lerner, Interpret.: Paul 1 Danneman, Pat Michael) - 1967, EMI Records Ltd. High -

Music by BENJAMIN BRITTEN Libretto by MYFANWY PIPER After a Story by HENRY JAMES Photo David Jensen

Regent’s Park Theatre and English National Opera present £4 music by BENJAMIN BRITTEN libretto by MYFANWY PIPER after a story by HENRY JAMES Photo David Jensen Developing new creative partnerships enables us to push the boundaries of our artistic programming. We are excited to be working with Daniel Kramer and his team at English National Opera to present this new production of The Turn of the Screw. Some of our Open Air Theatre audience may be experiencing opera for the first time – and we hope that you will continue that journey of discovery with English National Opera in the future; opera audiences intrigued to see this work here, may in turn discover the unique possibilities of theatre outdoors. Our season continues with Shakespeare’s As You Like It directed by Max Webster and, later this summer, Maria Aberg directs the mean, green monster musical, Little Shop of Horrors. Timothy Sheader William Village Artistic Director Executive Director 2 Edward White Benson entertained the writer one One, about the haunting of a child, leaves the group evening in January 1895 and - as James recorded in breathless. “If the child gives the effect another turn of There can’t be many his notebooks - told him after dinner a story he had the screw, what do you say to two children?’ asks one ghost stories that heard from a lady, years before. ‘... Young children man, Douglas, who says that many years previously he owe their origins to (indefinite in number and age) ... left to the care of heard a story too ‘horrible’ to admit of repetition. -

Four Plays by Frank Wedekind

TRAGEDIES OF SEX TRAGEDIES OF SEX BY FRANK WEDEKIND Translation and Introduction by SAMUEL A ELIOT, Jr. Spring’s Awakening (Fruhlings Erwachen) Earth-Spirit (Erdgeist) Pandora’s Box (Die Buchse der Pandora) Damnation 1 (Tod und Teufel) FRANK HENDERSON ftj Charing Cross Road, London, W.C. 2 CAUTION.—All persons are hereby warned that the plays publish 3d in this volume are fully protected under international copyright laws, and are subject to royalty, and any one presenting any of said plays without the consent of tho Author or his recognized agents, will be liable to the penalties by law provided. Both theatrical and motion picture rights are reserved. Printed in the TJ. S. A. CONTENTS PAGE Introduction vii Spring’s Awakening (Fruhlingserwachen) 1 Earth-Spirit (Erdgeist) Ill Pandora’s Box (Buchse der Pandora) . 217 Damnation! (Tod und Teufel) ...... 305 INTRODUCTION Frank Wedekind’s name is widely, if vaguely, known by now, outside of Germany, and at least five of his plays have been available in English form for qui^e some years, yet a resume of biographical facts and critical opinions seems necessary as introduction to this—I will not say authoritative, but more care- ful—book. The task is genial, since Wedekind was my special study at Munich in 1913, and I translated his two Lulu tragedies the year after. The timidity or disapprobation betrayed in this respect by our professional critics of foreign drama makes my duty the more imperative. James Huneker merely called him “a naughty boy !” Percival Pollard tiptoed around him, pointing out a trait here and a trait there, like a menagerie-keeper with a prize tiger. -

The Secret Garden Playbill

PLAYBILL COGER THEATRE STREAMED COMMAND PERFORMANCE ENJOY THE SHOW! CRAIG HALL 106 • 417.836.5247 coal.missouristate.edu ART+DESIGN • COMMUNICATION • ENGLISH • MEDIA, JOURNALISM & FILM • MODERN & CLASSICAL LANGUAGES MUSIC • THEATER & DANCE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAMS: ELECTRONIC ARTS • MUSICAL THEATER DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE AND DANCE and MUSICAL THEATRE PROGRAM present Book and Lyrics by MARSHA NORMAN Music by LUCY SIMON based on the novel by FRANCES HODGSON BURNETT Original Broadway Production Produced by: Heidi Landesman Rick Steiner, Frederic H. Mayerson, Elizabeth Williams Jujamcyn Theatres/TV ASAHI and Dodger Productions Originally produced by the Virginia Stage Company, Charles Towers, Artistic Director SCENIC DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNERS COSTUME DESIGNER MICHELLE HARVEY LILLIAN HILMES ABAGAIL M. JONES MICHEAL FOSTER SOUND DESIGNER VOCAL DIRECTOR TECHNICAL DIRECTOR LEVI MANNERS ANN MARIE DAEHN CHRIS DEPRIEST MARKETING DIRECTOR CONDUCTOR STAGE MANAGER MARK TEMPLETON CHRISTOPHER KELTS LIBBY CASEY CHOREOGRAPHER AZARIA HOGANS MUSIC DIRECTION BY HEATHER CHITTENDEN-LUELLEN DIRECTION BY ROBERT WESTENBERG SPRINGFIELD, MISSOURI SEPTEMBER 15–18, 2020 COGER THEATRE PRODUCTION STREAMED THROUGH SHOWTIX4U.COM CAST LILY ......................................................................................................... ANNA PENNINGTON MARY LENNOX............................................................................................BROOKE VERBOIS MRS. MEDLOCK .......................................................................................MCKENNA -

Macbeth William Shakespeare

AWARD WINNING LAZARUS THEATRE COMPANY www.lazarustheatrecompany.com Macbeth William Shakespeare Weird Sister / Macduff / Murderer - David Clayton Training - Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. Previous Lazarus credits include; Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward II, Ricky Dukes, Tristan Bates Threatre & Greenwich Theatre. Bottom, Midsummer Nights Dream, Ricky Dukes, Greenwich Theatre. Trinculo, The Tempest, Ricky Dukes, Greenwich Theatre. Guard of Herodias, Salomé, Ricky Dukes, Greenwich Theatre. Banquo / Apparition - Lewis Davidson Training - Kingston University Drama. Previous Lazarus credits include; Vindici, The Revenger’s Tragedy, Gavin Harrington-Odedra, Brockley Jack Studio Theatre. Edmund, Kind Lear, Ricky Dukes, GreenwichTheatre. Jupiter, Dido - Queen of Carthage, Ricky Dukes, Greenwich Theatre. Oliver De Boys, As You Like It, Gavin Harrington-Odedra, The Space. Duke Alba, Don Carlos, Ricky Dukes, Blue Elephant Theatre. Previous credits include; Ensemble, Wildefire, Maria Aberg, Hampstead Theatre. Ross MacDonald, Dreams From The Pit, Emma King-Farlow, Palace Theatre London. Icarus, Icarus – A Story Of Flight, Jake Lindsey, C Venues Edinburgh. Ryan, Sidings, Tom King, Rose Theatre Kingston. One Man Show, Sideshow, Jake Lindsey, C Venues Edinburgh. Lysander, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Rhona Mitchell, Lemon Tree Theatre. Lady Macbeth - Alice Emery Training - Drama Centre London and Stella Mann College of Performing Arts. Previous Lazarus credits (as RJ Seeley) Donado in ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore, Ricky Dukes, Tristan Bates Theatre; Chorus Leader in The Bacchae, Gavin Harrington-Odedra, The Blue Elephant; Fluellen in Henry V, Ricky Dukes, Union Theatre and the rehearsed reading of Polly at the Brockley Jack. Previous credits include Titania in A Midsummer Nights Dream, Laura Colgan, C Theatre; Theresa May/Ralph/Mrs Corbyn/various in Brexit the Musical, Lucy Appleby, Canal Cafe Theatre; Rosalind in As You Like It, Ross Livingstone, Barnes Theatre. -

Sponsored by CONTENTS MEET the TEAM

Sponsored by CONTENTS MEET THE TEAM 2 An introduction to Nottingham Playhouse Cast 3 Meet the Team David Albury – Prince 6 The Story Training: The Central School of Speech and Drama. 7 Our production Theatre includes: Junior Clerk in Committee... (Donmar Warehouse) directed by Adam Penford; Fleetwood in The Life (Southwark Playhouse) directed by Michael Blakemore; 8 Rehearsal photography Jimmy in Exposure The Musical (St. James Theatre); Billy Gray in Only The Brave (Wales 9 An interview with our Designer Millenium Centre); The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe (Birmingham Rep); Lead Vocalist in You Won't Succeed on Broadway if You Don't Have Any Jews (St. James 10 Activities and Fun Things to do at home or in the Classroom Theatre & Tel Aviv); Oliver Barrett IV in Love Story (Union Theatre); u/s Jake in Porgy and 14 An Interview with Cinderella Bess (Open Air Theatre) directed by Timothy Sheader; Zack in Bare (Greenwich Theatre); understudied and played Simba in The Lion King (National Tour). Most recently: Smokey Robinson in Motown the Musical (Shaftesbury Theatre). WELCOME Gabrielle Brookes – Cinderella We create theatre that’s bold, thrilling and proudly made in Nottingham. Gabrielle could recently be seen in our Zoom play for young audiences, Noah and the Awarded Regional Theatre of the Year 2019 by The Stage, Nottingham Playhouse is one of the country’s leading Peacock. producing theatres and creates a range of productions throughout the year, from timeless classics to innovative Theatre credits include: Anna Bella Eema (Arcola Theatre), A Midsummer Night's Dream family shows and adventurous new commissions. -

2019 Annual Review

2019 ANNUAL REVIEW We receive no public subsidy with over 90% of our income generated from ticket sales, and OUR 2019 SEASON ENGAGED yet we have maintained our lowest ticket price of £25 for seven years, increasing the number of tickets available at that price by 93%. At the same time, membership of our BREEZE WITH 142,500 VISITORS scheme – where those aged 18-25 can get tickets for £10 – has increased by 37% over the ACROSS 18 WEEKS, BUILDING past 12 months. Opening with Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, a play which celebrates what it means to be ON EXISTING PARTNERSHIPS, human and the bonds of community, we offered increased access to our theatre by working with local charities, notably Camden Disability Action and Age UK Camden, and introduced ESTABLISHING NEW ONES, AND a relaxed performance during the run. Hansel and Gretel continued our partnership with English National Opera, building on the success of our Olivier Award nominated production of CHAMPIONING DIVERSITY IN The Turn of the Screw and, through Pimlico Musical Foundation, gave 33 children from one EVERYTHING WE DO. of London’s most complex communities the opportunity of appearing alongside professional singers. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, we incorporated British Sign Language in a cast which included our first deaf performer, and reintroduced BSL interpreted performances to our schedule (all productions in 2020 will include BSL interpreted performances). Following the phenomenal success of Jesus Christ Superstar, which played to sell-out audiences at the Barbican this summer ahead of its North American tour, we continued our relationship with Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber by presenting Jamie Lloyd’s innovative new staging of Evita – a production which we look forward to taking to the Barbican next summer. -

NATALIE GALLACHER CDG Casting Director Pippa Ailion Casting 07950 299 379 [email protected]

NATALIE GALLACHER CDG Casting Director Pippa Ailion Casting 07950 299 379 [email protected] THEATRE as Casting Director for Pippa Ailion Casting: 2021 Moulin Rouge! The Musical Piccadilly dir. Alex Timbers 2021 Get Up, Stand Up! Lyric dir. Clint Dyer 2020 Hello Dolly Adelphi dir. Dominic Cooke 2020 Dreamgirls UK Tour UK Tour dir. Casey Nicholaw 2020 Sunny Afternoon UK Tour UK Tour dir. Edward Hall 2020 Orfeus: A House Music Opera Young Vic dir. Charles Randolph Wright 2019-2020 On Your Feet! Coliseum & UK Tour dir. Jerry Mitchell 2019 The Wizard Of Oz Leeds Playhouse dir. James Brining 2019 Robin Hood Salisbury Playhouse dir. Gareth Machin 2019 The Book Of Mormon UK & International Tour dir. Casey Nicholaw & Trey Parker 2019 Grandpa’s Great Escape Arena Tour dir. Sean Foley 2019 Tree Young Vic dir. Kwame Kwei-Armah 2019 Big! (selected casting) Dominion dir. Morgan Young 2018- present Come From Away The Abbey, Dublin & Phoenix dir. Christopher Ashley 2018-present Tina: The Tina Turner Musical Aldwych dir. Phyllida Lloyd 2018 Teddy Watermill, The Vaults & tour dir. Eleanor Rhode 2017 Paw Patrol UK Arena Tour dir. Theresa Borg 2017 Gutted Marlowe, Canterbury dir. Nicola Samer 2016 Dreamgirls Savoy dir. Casey Nicholaw 2016 The Go Between Apollo dir. Roger Haines 2016 Charlie & The Chocolate Factory Theatre Royal, Drury Lane dir. Sam Mendes 2015 Motown Shaftesbury Theatre dir. Charles Randolph Wright 2015-2017 Sunny Afternoon Harold Pinter & UK Tour dir. Edward Hall 2014 Far Away Young Vic dir. Kate Hewitt 2012-present The Book Of Mormon Prince of Wales dir. Casey Nicholaw & Trey Parker 2005-present The Lion King Lyceum dir. -

Regent's Park Open Air Theatre Announce Their

PRESS RELEASE REGENT’S PARK OPEN AIR THEATRE ANNOUNCE THEIR 2020 SEASON • Directed by Timothy Sheader, the 2020 season opens with 101 DALMATIANS, a newly commissioned musical with book by Zinnie Harris and music and lyrics by Douglas Hodge, based on the book by Dodie Smith • Kimberley Sykes directs Shakespeare’s ROMEO AND JULIET • Director Timothy Sheader reunites with Superstar choreographer Drew McOnie to rediscover Rodgers and Hammerstein’s CAROUSEL Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre have today announced their 2020 season which opens with their first newly commissioned musical, 101 Dalmatians (16 May – 21 June), based on Dodie Smith’s iconic story set in the heart of Regent’s Park with book by Zinnie Harris and music and lyrics by Douglas Hodge. The production is directed by Timothy Sheader, with puppetry designed and directed by Toby Olié. Also confirmed are Katrina Lindsay (Set and Costume Designer), Liam Steel (Choreographer), Sarah Travis (Musical Supervisor and Orchestrator), Howard Hudson (Lighting Designer) and Tarek Merchant (Musical Director). Casting is by Jill Green, with children’s casting by Verity Naughton. Kimberley Sykes then directs Romeo and Juliet (27 June – 25 July), Shakespeare’s timeless story of two young people torn apart by a divided society and forbidden love. Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre is celebrated for their innovative approach to musicals, and the 2020 season concludes with Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel (31 July – 19 September). Featuring a score that includes ‘If I Loved You’ and ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, director Timothy Sheader reunites with Jesus Christ Superstar choreographer Drew McOnie.