Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tese Correções Defesa-23-7-16

! ALEXANDER SCRIABIN THE DEFINITION OF A NEW SOUND SPACE IN THE CRISIS OF TONALITY Luís Miguel Carvalhais Figueiredo Borges Coelho Tese apresentada à UniversidadeFiguiredo de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Musicologia ORIENTADORES: Paulo de Assis Benoît Gibson ÉVORA, JULHO DE 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA ALEXANDER SCRIABIN THE DEFINITION OF A NEW SOUND SPACE IN THE CRISIS OF TONALITY Luís Miguel Carvalhais Figueiredo Borges Coelho Tese apresentada à Universidade de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Musicologia ORIENTADORES: Paulo de Assis Benoît Gibson ÉVORA, JULHO DE 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA iii To Marta, João and Andoni, after one year of silent presence. To my parents. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my friend Paulo de Assis, for all his dedication and encouragement in supervising my research. His enthusiasm, knowledge and always-challenging opinions were a permanent stimulus to look further. I thank Benoît Gibson for having accepted to co-supervise my work, despite my previous lack of any musicological experience. I extend my gratitude to Stanley Hanks, whose willingness to supervise my English was only limited by the small number of pages I could submit to his advice before the inexorable deadline. Thanks are also due to my former piano teachers—Amélia Vilar, Isabel Rocha, Vitaly Margulis, Dimitri Bashkirov and Galina Egyazarova—for having taught me everything I know about music. To my dear friends Catarina and André I will be always grateful: without their indefatigable assistance in the final assembling of this dissertation, my erratic relation with the writing software would have surely slipped into chaos. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

Copyright Page

Copyright by Michael Dylan Sailors 2013 ! The Dissertation Committee for Michael Dylan Sailors certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Manhattan by Midnight: A Suite for Jazz Orchestra in Three Movements Committee: _______________________________________ John Mills, Supervisor _______________________________________ Jeff Hellmer, Co-Supervisor _______________________________________ John Fremgen _______________________________________ Thomas O’Hare _______________________________________ Laurie Scott Young _______________________________________ Bruce Pennycook ! Manhattan by Midnight: A Suite for Jazz Orchestra in Three Movements by Michael Dylan Sailors, B. Music; M. Music Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 ! Dedication To my father, whose support and guidance has meant the world to me. ! Acknowledgements Special thanks to: Jeff Hellmer, John Mills and John Fremgen for their guidance and mentorship throughout my entire doctoral experience; to Duke Ellington, Thad Jones, Ed Neumeister, and Wynton Marsalis for inspiring me to compose the music found herein. ! ! v Manhattan by Midnight: A Suite for Jazz Orchestra in Three Movements Michael Dylan Sailors, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2013 Supervisor: John Mills Co-Supervisor: Jeff Hellmer Manhattan by Midnight is a three-movement work for jazz orchestra -

The Compositional Language of Kenny Wheeler

THE COMPOSITIONAL LANGUAGE OF KENNY WHEELER by Paul Rushka Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal March 2014 A paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of D.Mus. Performance Studies ©Paul Rushka 2014 2 ABSTRACT The roots of jazz composition are found in the canon ofthe Great American Songbook, which constitutes the majority of standard jazz repertoire and set the compositional models for jazz. Beginning in the 1960s, leading composers including Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock began stretching the boundaries set by this standard repertoire, with the goal of introducing new compositional elements in order to expand that model. Trumpeter, composer, and arranger Kenny Wheeler has been at the forefront of European jazz music since the late 1960s and his works exemplify a contemporary approach to jazz composition. This paper investigates six pieces from Wheeler's songbook and identifies the compositional elements of his language and how he has developed an original voice through the use and adaptation of these elements. In order to identify these traits, I analyzed the melodic, harmonic, structural and textural aspects of these works by studying both the scores and recordings. Each of the pieces I analyzed demonstrates qualities consistent with Wheeler's compositional style, such as the expansion oftonality through the use of mode mixture, non-functional harmonic progressions, melodic composition through intervallic sequence, use of metric changes within a song form, and structural variation. Finally, the demands of Wheeler's music on the performer are examined. 3 Resume La composition jazz est enracinee dans le Grand repertoire American de la chanson, ou "Great American Songbook", qui constitue la plus grande partie du repertoire standard de jazz, et en a defini les principes compositionnels. -

The War to End War — the Great War

GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE GIVING WAR A CHANCE, THE NEXT PHASE: THE WAR TO END WAR — THE GREAT WAR “They fight and fight and fight; they are fighting now, they fought before, and they’ll fight in the future.... So you see, you can say anything about world history.... Except one thing, that is. It cannot be said that world history is reasonable.” — Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoevski NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND “Fiddle-dee-dee, war, war, war, I get so bored I could scream!” —Scarlet O’Hara “Killing to end war, that’s like fucking to restore virginity.” — Vietnam-era protest poster HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1851 October 2, Thursday: Ferdinand Foch, believed to be the leader responsible for the Allies winning World War I, was born. October 2, Thursday: PM. Some of the white Pines on Fair Haven Hill have just reached the acme of their fall;–others have almost entirely shed their leaves, and they are scattered over the ground and the walls. The same is the state of the Pitch pines. At the Cliffs I find the wasps prolonging their short lives on the sunny rocks just as they endeavored to do at my house in the woods. It is a little hazy as I look into the west today. The shrub oaks on the terraced plain are now almost uniformly of a deep red. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1914 World War I broke out in the Balkans, pitting Britain, France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, the USA, and Japan against Austria, Germany, and Turkey, because Serbians had killed the heir to the Austrian throne in Bosnia. -

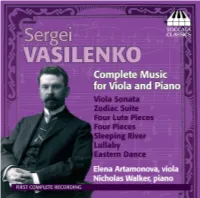

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

Wednesday Slide Conference 2008-2009

PROCEEDINGS DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY PATHOLOGY WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2008-2009 ARMED FORCES INSTITUTE OF PATHOLOGY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20306-6000 2009 ML2009 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Department of Veterinary Pathology WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2008-2009 100 Cases 100 Histopathology Slides 249 Images PROCEEDINGS PREPARED BY: Todd Bell, DVM Chief Editor: Todd O. Johnson, DVM, Diplomate ACVP Copy Editor: Sean Hahn Layout and Copy Editor: Fran Card WSC Online Management and Design Scott Shaffer ARMED FORCES INSTITUTE OF PATHOLOGY Washington, D.C. 20306-6000 2009 ML2009 i PREFACE The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Department of Veterinary Pathology has conducted a weekly slide conference during the resident training year since 12 November 1953. This ever- changing educational endeavor has evolved into the annual Wednesday Slide Conference program in which cases are presented on 25 Wednesdays throughout the academic year and distributed to 135 contributing military and civilian institutions from around the world. Many of these institutions provide structured veterinary pathology resident training programs. During the course of the training year, histopathology slides, digital images, and histories from selected cases are distributed to the participating institutions and to the Department of Veterinary Pathology at the AFIP. Following the conferences, the case diagnoses, comments, and reference listings are posted online to all participants. This study set has been assembled in an effort to make Wednesday Slide Conference materials available to a wider circle of interested pathologists and scientists, and to further the education of veterinary pathologists and residents-in-training. The number of histopathology slides that can be reproduced from smaller lesions requires us to limit the number of participating institutions. -

Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Koenig Books Isbn 978-3-86560-706-5 Early 20Th Century Russia · Andrey Smirnov

SOUND IN Z Russia, 1917 — a time of complex political upheaval that resulted in the demise of the Russian monarchy and seemingly offered great prospects for a new dawn of art and science. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, artists and enthusiasts developed innumerable musical and audio inventions, instruments and ideas often long ahead of their time – a culture that was to be SOUND IN Z cut off in its prime as it collided with the totalitarian state of the 1930s. Smirnov’s account of the period offers an engaging introduction to some of the key figures and their work, including Arseny Avraamov’s open-air performance of 1922 featuring the Caspian flotilla, artillery guns, hydroplanes and all the town’s factory sirens; Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre; Alexei Gastev, the polymath who coined the term ‘bio-mechanics’; pioneering film maker Dziga Vertov, director of the Laboratory of Hearing and the Symphony of Noises; and Vladimir Popov, ANDREY SMIRNO the pioneer of Noise and inventor of Sound Machines. Shedding new light on better-known figures such as Leon Theremin (inventor of the world’s first electronic musical instrument, the Theremin), the publication also investigates the work of a number of pioneers of electronic sound tracks using ‘graphical sound’ techniques, such as Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, Nikolai Voinov, Evgeny Sholpo and Boris Yankovsky. From V eavesdropping on pianists to the 23-string electric guitar, microtonal music to the story of the man imprisoned for pentatonic research, Noise Orchestras to Machine Worshippers, Sound in Z documents an extraordinary and largely forgotten chapter in the history of music and audio technology. -

GLOSSARY the Following Terms and Concepts Are Studied in Analytical Techniques I and II. in General, the Items in Bold Typeset

GLOSSARY The following terms and concepts are studied in Analytical Techniques I and II. In general, the items in bold typeset are discussed in Analytical Techniques II, while the items in regular typeset are studied in Analytical Techniques I. Aggregates (in 12-tone technique) Allen Forte’s List (set-theory) Altered dominant chords Altered predominant chords Altered transition (in sonata form) Answers: real vs. tonal (in fugue) Ars Antiqua Ars Nova Augmentation (rhythmic) Augmented dominant chords Augmented-sixth chords: 3 types Augmented-sixth chords: voice leading Axis System Baroque period Basso continuo Binary form Bitonality Cadences (in Medieval and Renaissance music) Cadences (in tonal music) Cadence rhyme (in binary form) Cadential episode (in fugue) Cadenza (in classical concerto) Caesura Canon vs. imitation Cantus firmus Cantus firmus mass Centric vs. Tonal music Chaconne Change of mode Changing meter Character pieces (Romantic period) Chorale prelude Chords of addition Chords of omission Chromatic mediants: 3 types Chromatic modulation Chromatic scale Church modes Circle-of-fifths progression Closely related keys Closing (in sonata form) Coda Codetta Color (in isorhythmic technique) Combinatoriality (12-tone) Common-tone augmented chord Common-tone diminished chord Common-tone dominant chord Common-tone modulation Compound melody Compound ternary form Concertato Concerto form Concerto grosso Continuous variation Counter-exposition (in fugue) Counterpoint Counter-reformation Crab canon Cross rhythm Da capo Dance suite (Baroque -

Dracula Thesis

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Master's Theses Student Research 6-1-2020 Dracula Thesis Justino Perez Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses Recommended Citation Perez, Justino, "Dracula Thesis" (2020). Master's Theses. 206. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses/206 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2020 Justino E. Perez ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School DRACULA TRIO A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Justino E. Perez College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Department of Theory and Composition May 2020 This Thesis by: Justino E. Perez Entitled: Dracula Trio has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Master of Music in College of Performing and Visual Arts in School of Music, Department of Theory and Composition Accepted by the Thesis Committee ____________________________________________________ Paul Elwood, Ph.D., Chair ____________________________________________________ Louis Drizhal, M.M., Committee Member Accepted by the Graduate School ____________________________________________________________ Cindy Wesley Interim Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Perez, Justino E. Dracula Trio. Unpublished Master of Music thesis, University of Northern Colorado, 2020. Dracula Trio is a three-movement work for violin, violoncello, and piano-forte. This work follows an abbreviated plot of the popular video game and animated show by the name of Castlevania.