Isbn: 978-602-50956-6-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED a HOME for the ANGELS CHILD Mrs

Directory of Social Welfare and Development Agencies (SWDAs) with VALID REGISTRATION, LICENSED TO OPERATE AND ACCREDITATION per AO 16 s. 2012 as of March, 2015 Name of Agency/ Contact Registration # License # Accred. # Programs and Services Service Clientele Area(s) of Address /Tel-Fax Nos. Person Delivery Operation Mode NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED A HOME FOR THE ANGELS CHILD Mrs. Ma. DSWD-NCR-RL-000086- DSWD-SB-A- adoption and foster care, homelife, Residentia 0-6 months old NCR CARING FOUNDATION, INC. Evelina I. 2011 000784-2012 social and health services l Care surrendered, 2306 Coral cor. Augusto Francisco Sts., Atienza November 21, 2011 to October 3, 2012 abandoned and San Andres Bukid, Manila Executive November 20, 2014 to October 2, foundling children Tel. #: 562-8085 Director 2015 Fax#: 562-8089 e-mail add:[email protected] ASILO DE SAN VICENTE DE PAUL Sr. Enriqueta DSWD-NCR RL-000032- DSWD-SB-A- temporary shelter, homelife Residentia residential care -5- NCR No. 1148 UN Avenue, Manila L. Legaste, 2010 0001035-2014 services, social services, l care and 10 years old (upon Tel. #: 523-3829/523-5264/522- DC December 25, 2013 to June 30, 2014 to psychological services, primary community-admission) 6898/522-1643 Administrator December 24, 2016 June 29, 2018 health care services, educational based neglected, Fax # 522-8696 (Residential services, supplemental feeding, surrendered, e-mail add: [email protected] Care) vocational technology program abandoned, (Level 2) (commercial cooking, food and physically abused, beverage, transient home) streetchildren DSWD-SB-A- emergency relief - vocational 000410-2010 technology progrm September 20, - youth 18 years 2010 to old above September 19, - transient home- 2013 financially hard up, (Community no relative in based) Manila BAHAY TULUYAN, INC. -

The GEMMA Fund Fifth Annual Report: 2013-2014

The GEMMA Fund Fifth Annual Report: 2013-2014 AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico *Photo: A pro-abortion activist participating in the September 25th, 2012 demonstration in favor of legal- ization of abortion in Montevideo, Uruguay. This action was a protest of the decriminalization law which passed in October 2012, because the law (currently in place) is so restrictive. More than a dozen women were part of the nude demonstration, painted orange with owers, while others were dressed in orange. Demonstrators held signs saying "Aborto Legal" (Legal Abortion). Marta Agunin, who directs Women and Health [MYSU], a non-governmental organization in Uruguay, complained “This is not the law for which we fought for more than 25 years” Developed and designed by Jenny Holl and Gelsey Hughes, March 2015. *http://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Uruguay-poised-to-legalize-abortion-3893945.php#photo-3506159 Mission The GEMMA Fund supports Emory University graduate students’ research and their collaborations with public health organizations to contribute to the prevention of maternal deaths from abortion. Background The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 21 million women worldwide receive unsafe abortions every year, resulting in 47,000 maternal deaths annually (13% of all maternal deaths). Nearly all (98%) of unsafe abortions take place in developing countries. The WHO estimates that if all women were able to attain the same quality of abortion services available in the United States, fewer than 100 women would die from abortions each year, but for -

Philippines: the Protection Offered to Female Victims of Sexual Abuse Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 13 March 2008 PHL102719.E Philippines: The protection offered to female victims of sexual abuse Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa Freedom House reports that "[r]ape, domestic violence, [and] sexual harassment on the job ... continue to be major problems despite efforts in government and civil society to protect women from violence and abuse" (2007). Similarly, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2006 states that violence against women "remained a serious problem" (US 6 Mar. 2007, Sec. 5). According to the Philippine Star, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) reported 22,724 victims of sexual abuse from 2000 to 2005 (27 Sept. 2007). The DSWD, which provides programs and services for specific groups including women (Philippines n.d.a), reports on its website that it provided assistance to 237 female victims of rape, 91 female victims of incest and 5 female victims of "acts of lasciviousness" in 2006 (ibid. n.d.b). According to the National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women (NCRFW), the number of cases of violence against women increased from 1,100 in 1996 to 6,505 in 2005, and police records for 2005 indicate that 17.2 percent of cases reported to the police were rape cases (Philippines Mar. 2006). The Anti-Rape Law of 1997, which amends the definitions of the crime of rape in the Revised Penal Code, also defines marital rape as a crime unless the wife forgives the offender (i.e., her husband) (ibid. -

3.Philippines

LAWS AND POLICIES AFFECTING THEIR REPRODUCTIVE LIVES PAGE 123 3. Philippines Statistics GENERAL Population ■ Total population (millions): 83.1.1 ■ Population by sex (thousands): 40,418.2 (female) and 40,990.0 (male).2 ■ Percentage of population aged 0–14: 36.5.3 ■ Percentage of population aged 15–24: 20.3.4 ■ Percentage of population in rural areas: 39.5 Economy ■ Annual percentage growth of gross domestic product (GDP): 3.5.6 ■ Gross national income per capita: USD 1,080.7 ■ Government expenditure on health: 1.5% of GDP.8 ■ Government expenditure on education: 2.9% of GDP.9 ■ Percentage of population below the poverty line: 37.10 WOMEN’S STATUS ■ Life expectancy: 73.1 (female) and 68.8 (male).11 ■ Average age at marriage: 23.8 (female) and 26.3 (male).12 ■ Labor force participation: 54.8 (female) and 84.3 (male).13 ■ Percentage of employed women in agricultural labor force: Information unavailable. ■ Percentage of women among administrative and managerial workers: 58.14 ■ Literacy rate among population aged 15 and older: 96% (female) and 96% (male).15 ■ Percentage of female-headed households: 11.16 ■ Percentage of seats held by women in national government: 18.17 ■ Percentage of parliamentary seats occupied by women: 15.18 CONTRACEPTION ■ Total fertility rate: 3.03.19 ■ Contraceptive prevalence rate among married women aged 15–49: 49% (any method) and 33% (modern method).20 ■ Prevalence of sterilization among couples: 10.4% (total); 10.3% (female); 0.1% (male).21 ■ Sterilization as a percentage of overall contraceptive prevalence: 22.4.22 MATERNAL HEALTH ■ Lifetime risk of maternal death: 1 in 90 women.23 ■ Maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births: 200.24 ■ Percentage of pregnant women with anemia: 50.25 ■ Percentage of births monitored by trained attendants: 60.26 PAGE 124 WOMEN OF THE WORLD: ABORTION ■ Total number of abortions per year: Information unavailable. -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Laws on Violence Against Women in the Philippines

EGM/GPLVAW/2008/EP.12 22 August 2008 ENGLISH only United Nations Nations Unies United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women Expert Group Meeting on good practices in legislation on violence against women United Nations Office at Vienna, Austria 26 to 28 May 2008 Laws on Violence against Women in the Philippines Expert Paper prepared by: Rowena V. Guanzon* Professor, University of the Philippines College of Law Steering Committee Member, Asia Cause Lawyers Network * The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations. 1 EGM/GPLVAW/2008/EP.12 22 August 2008 ENGLISH only Background: Since 1995, violence against women (VAW) has captured the attention of the government and legislators in the Philippines, propelled by the demand of a growing women’s human rights movement and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, its Optional Protocol1 as well as other international conventions. The Beijing Conference on Women in 1995 heightened the demand of women’s rights advocates for laws protecting women from violence. Progressive reforms in laws protecting women was brought about by several factors beginning with the democratization process that began in the 1986 People Power Revolution after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship, the 1987 Constitution2 that has specific provisions on the rights of women and fundamental equality before the law of men and women, the increasing number of women’s organizations in the provinces with links to Metro Manila based women’s rights organizations,3 and the participation of women legislations who are becoming increasingly aware of the need for gender equality and the elimination of VAW. -

PHILIPPINES: Country Gender Profile

PHILIPPINES: Country Gender Profile July 2008 Cristina Santiago In-House Consultant Japan International Cooperation Agency JICA does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this Paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use Contents List of Abbreviations………………………………………………………………..viii 1. Basic Profile 1.1 Socio-Economic……………………………………………………1 1.2 Health………………………………………………………………3 1.3 Education………………………………………………………......4 2. Government Policy on Gender and the National Machinery 2.1 Women’s Situation in the Philippines……………………………...5 2.2 Government Policy on Gender…………………………………….7 2.3 National Machinery ……………………………………………….7 3. Current Situation of Women by Sector 3.1 Education Education in the Philippines……………………………………….11 Expenditure on Education………………………………………....11 Basic Key Indicators……………………………………………….12 Basic and Functional Literacy Rates……………………………….15 3.2 Health Health Situation in the Philippines…………………………………17 Maternal Mortality………………………………………………….17 Contraception……………………………………………………….18 Fertility Rates………………………………………….....................21 Abortion………………………………………………………….....23 Infant Mortality and Under 5 Mortality………………………….....24 Public Health Indicators in Southeast Asia…………………………25 Women in Especially Difficult Circumstances……………………..26 Violence Against Women and Children………………………….....27 ii 3.3 Agriculture Agriculture in the Philippines ……………………………………..29 Land Ownership……………………………………………………30 Women’s Participation in Agriculture………………………………30 Indigenous Women in Traditional Agriculture…………………......32 -

Fma.Ph; [email protected]

Submission on domestic violence in the context of COVID-19 to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences June 30, 2020 For all inquiries related to this submission, please contact: Liza S. Garcia Executive Director Foundation for Media Alternatives Quezon City, Philippines [email protected]; [email protected] Contributors to this report (in alphabetical order): Liza Garcia, FMA Christina Lopez, FMA Jessamine Pacis, FMA Janina Sarmiento, FMA Nina Somera, FMA Acknowledgements: We would also like to thank the Association for Progressive Communications for their support in the creation of this report. 1 FMA Submission to the UNSR on Violence against women | Table of Contents About Foundation for Media Alternatives 03 Introduction and Context 04 Legal framework 06 Violence against women in the Philippines in the context of COVID-19 09 Support to VAW victims 11 Access to legal measures 12 Access to health services 13 Preventing VAW in the time of COVID-19 14 Role of technology in a crisis 15 Conclusions and recommendations 17 2 FMA Submission to the UNSR on Violence against women | About FMA The Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) is a non-stock, non-profit organization founded in 1987 soon after the People Power Revolution in the Philippines. Its mission is to assist citizens and communities - especially civil society organizations and other disadvantaged sectors - in their strategic and appropriate use of various communications media for democratization and popular empowerment. In 1996, FMA focused on information and communications technologies (ICTs) and the emerging phenomenon of the Internet, and began to frame communication rights as human rights. -

President Manny Pacquiao Dizon

JANUARY 2021 President Manny Pacquiao It can and It may Happen, as Pacquiao takes over as president of Duterte’s PDP-Laban MANILA - For now, president of Duterte. Boxer-turned-senator Pacquiao of the Party to one with new, ‘mod- PDP-Laban. The oathtaking ceremony took replaced Sen. Aquilino “Koko” Pi- ern’ ideas and one who has the time, As the 2022 elections draw nearer, place December 2, 2019, with House mentel III, who will now serve as the energy, and boldness to prepare the Sen. Manny Pacquiao was sworn in as Speaker Lord Allan Velasco also party’s executive vice chairman. the new president of PDP-Laban, the taking his oath as the party’s new “Senator Koko Pimentel has passed PRESIDENT PACQUIAO political party of President Rodrigo executive president. on the practical day-to-day leadership continued on page 21 Look Back Real Session Road, Baguio 1960’S Fan Girl beats veterans for Best Filipino health workers in the frontline of Actress vaccine history Award TORONTO - On the showing “light at the end opposite sides of the of the tunnel.” Atlantic, one was admin- Filipino nurse May istering it, the other was Parsons delivered Pfiz- for role in receiving it. er-BioNTech’s coronavirus ‘Now it feels like there vaccine to 90-year-old is light at the end of the Margaret Keenan at a tunnel,’ says Filipino local hospital in Coventry. Fan Girl nurse May Parsons, who Keenan is the first person has been working with in world to get the vac- the UK’s National Health cine, approved just a week Service for 24 years ago in Britain. -

The Role of Cultural Radios in Campursari Music Proliferation in East Java

ETNOSIA: JURNAL ETNOGRAFI INDONESIA Volume 5 Issue 2, DECEMBER 2020 P-ISSN: 2527-9319, E-ISSN: 2548-9747 National Accredited SINTA 2. No. 10/E/KPT/2019 A Virtual Ethnography Study: The Role of Cultural Radios in Campursari Music Proliferation in East Java Zainal Abidin Achmad1, Rachmah Ida2, Mustain3 1 Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Jawa Timur, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Campursari music is a trend on the radio and a favorite of the people campursari music; of East Java, so it is shifting towards popular culture. This study aims cultural proximity; to uncover the proliferation of campursari music and the role of cultural radio; virtual cultural radios. This qualitative research uses a virtual ethnography ethnography method, which focuses on the physical presence and virtual text together. The subjects are technology (radio and communication How to cite: technology on the internet), humans (radio listeners), physical Achmad, Z.A., Ida, R., interactions, and virtual interactions. Data collection used participant Mustain. (2020). A observation through observation and interviews offline and online in Virtual Ethnography the form of various texts, writings, images, and audiovisuals on Study: The Role of Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Youtube. The Cultural Radios in informants of this study were four cultural experts, namely: Sumadi, Campursari Music Anton Sani, Ibnu Hajar, and Juwono. This study carried out Proliferation in East Java. participatory involvement for one year in the virtual world and 30 ETNOSIA: Jurnal days living in four cities: Surabaya, Nganjuk, Banyuwangi, and Etnografi Indonesia. -

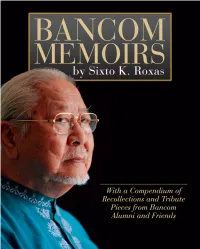

With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends

The ebook version of this book may be downloaded at www.xBancom.com This Bancom book project was made possible by the generous support of mr. manuel V. Pangilinan. The book launching was sponsored by smart infinity copyright © 2013 by sixto K. roxas Bancom memoirsby sixto K. roxas With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends Edited by eduardo a. Yotoko Published by PLDT-smart Foundation, inc and Bancom alumni, inc. (BaLi) contents Foreword by Evelyn R. Singson 5 Foreword by Francis G. Estrada 7 Preface 9 Prologue: Bancom and the Philippine financial markets 13 chapter 1 Bancom at its 10th year 24 chapter 2 BTco and cBTc, Bliss and Barcelon 28 chapter 3 ripe for investment banking 34 chapter 4 Founding eDF 41 chapter 5 organizing PDcP 44 chapter 6 childhood, ateneo and social action 48 chapter 7 my development as an economist 55 chapter 8 Practicing economics at central Bank and PnB 59 chapter 9 corporate finance at Filoil 63 chapter 10 economic planning under macapagal 71 chapter 11 shaping the development vision 76 chapter 12 entering the money market 84 chapter 13 creating the Treasury Bill market 88 chapter 14 advising on external debt management 90 chapter 15 Forming a virtual merchant bank 103 chapter 16 Functional merger with rcBc 108 chapter 17 asean merchant banking network 112 chapter 18 some key asian central bankers 117 chapter 19 asia’s star economic planners 122 chapter 20 my american express interlude 126 chapter 21 radical reorganization and BiHL 136 chapter 22 Dewey Dee and the end of Bancom 141 chapter 23 The total development company components 143 chapter 24 a changed life-world 156 chapter 25 The sustainable development movement 167 chapter 26 The Bancom university of experience 174 chapter 27 summing up the legacy 186 Photo Folio 198 compendium of recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom alumni and Friends 205 4 Bancom memoirs Bancom was absorbed by union Bank in 1981. -

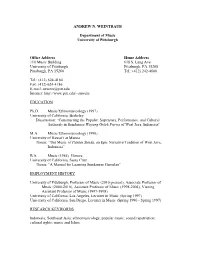

ANDREW N. WEINTRAUB Department of Music University Of

ANDREW N. WEINTRAUB Department of Music University of Pittsburgh Office Address Home Address 110 Music Building 618 S. Lang Ave University of Pittsburgh Pittsburgh, PA 15208 Pittsburgh, PA 15260 Tel.: (412) 242-4686 Tel.: (412) 624-4184 Fax: (412) 624-4186 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.pitt.edu/~anwein EDUCATION Ph.D. Music/Ethnomusicology (1997) University of California, Berkeley Dissertation: “Constructing the Popular: Superstars, Performance, and Cultural Authority in Sundanese Wayang Golek Purwa of West Java, Indonesia” M.A. Music/Ethnomusicology (1990) University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Thesis: “The Music of Pantun Sunda, an Epic Narrative Tradition of West Java, Indonesia” B.A. Music (1985) Honors University of California, Santa Cruz Thesis: “A Manual for Learning Sundanese Gamelan” EMPLOYMENT HISTORY University of Pittsburgh, Professor of Music (2010-present), Associate Professor of Music (2004-2010), Assistant Professor of Music (1998-2004), Visiting Assistant Professor of Music (1997-1998) University of California, Los Angeles, Lecturer in Music (Spring 1997) University of California, San Diego, Lecturer in Music (Spring 1996 - Spring 1997) RESEARCH KEYWORDS Indonesia; Southeast Asia; ethnomusicology; popular music; sound repatriation; cultural rights; music and Islam ANDREW N. WEINTRAUB 5/10/18 Page 2 PUBLICATIONS Books Vamping the Stage: Female Voices of Asian Modernities (co-editor with Bart Barendregt). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2017. Islam and Popular Culture in Indonesia and Malaysia (editor). London and New York: Routledge, 2011. • Reviewed in Journal of Asian Social Science; Sojourn; Asian Ethnology; Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia and Oceania; Asian Studies Review; Journal of Religion and Popular Culture; Political Studies Review; Musicultures.